Virtual Worlds and Virtual Economies

The Startups Building Virtual Worlds for Music, Socializing, Education, and Work

This is a weekly newsletter about tech, media, and culture. To receive this newsletter in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Virtual Worlds and Virtual Economies

In the spring, Nintendo’s Animal Crossing exploded in popularity. While most of the real world was in lockdown, players in the game were decorating their homes, catching fish, and socializing on a colorful, cartoonish island.

Soon, a peculiar thing began to happen: business executives started having work meetings in Animal Crossing. The pandemic was fueling Zoom fatigue, and fancy business lunches were out of the question; CEOs instead turned to a virtual world to dine with clients and other executives.

This new behavior wasn’t limited to Animal Crossing. One advertising executive met with an investment manager in Grand Theft Auto, where the pair robbed a bank together. (“It’s my version of golf,” said the ad exec.) Others held business meetings in Red Dead Redemption, a Western-themed game set in the American frontier of 1899:

Beyond work meetings, people began to express themselves through digital worlds. Some even put up Biden / Harris yard signs in Animal Crossing:

The pandemic is accelerating one of the most important trends of the Internet: the creation and normalization of virtual worlds and virtual economies.

Today, virtual worlds mostly take the form of multiplayer online games: Roblox players average nearly 3 hours per day in Roblox; Fortnite has been collectively played for 10.4 million years—about 52x the time that humans have occupied the Earth.

But virtual worlds are emerging in new forms, bleeding into parts of life from music to education to work. We’re slowly inching toward the “metaverse”—a term from the novel Snow Crash that describes a collective virtual shared space. (Roblox’s S-1 filing from last month mentions the term “metaverse” 16 times.) In the future, we’ll all spend hours each day as digital avatars or as ourselves in immersive virtual reality worlds.

Most importantly, virtual worlds will level the playing field. We’re living through unprecedented income inequality, with global wealth concentrated at the top. In the analog world, talent is equally distributed but opportunity is not. In virtual worlds, everyone will have equal access to opportunity: all a participant needs is Internet access. Virtual worlds and virtual economies will break down traditional barriers to wealth creation and wealth distribution.

Below are parts of life shifting to virtual worlds, and the companies behind the shift.

Music

In April, 46 million people watched Travis Scott’s “Astronomical” concert in Fortnite. Millions more watched across the Internet, and the YouTube video of the event has 112 million views.

Hosting a concert in a virtual world gave Scott unlimited creative freedom. He arrived on a purple comet, grew to the size of a skyscraper, and went underwater.

Last month, Roblox hosted a concert with Lil Nas X that attracted 33 million views.

While not all take place in virtual worlds, virtual concerts are becoming popular as the pandemic shuts down physical events and as online-first events become more creative and immersive.

Three startups powering virtual concerts are Maestro, Moment House, and Wave:

Maestro is a white-label platform: an artist can fully customize Maestro to fit her needs, with consumers never seeing Maestro’s name. Billie Eilish’s blockbuster concert from earlier this fall, for example, was powered by Maestro. Using Maestro’s mixed reality tech, Eilish was able to transport viewers into different worlds for each song.

Moment House is essentially a business-in-a-box platform for live concerts, enabling a long tail of artists to launch and monetize a virtual experience.

Wave, which recently received a strategic investment from Tencent, has powered concerts for Justin Bieber, John Legend, and The Weeknd. Wave turns artists into digital avatars for virtual concerts—similar to Fortnite and Roblox concerts—and airs concerts across the Internet. The Weeknd’s concert, for instance, aired on TikTok and drew 2 million viewers.

Socializing

A generation ago, online dating was stigmatized—it was embarrassing to have to resort to the Internet for dating. Today, online dating is fully mainstream:

Socializing through virtual worlds is following a similar arc. Second Life, an online virtual world developed by Linden Labs, became popular in the late 2000s but was too early—it faded from popularity over the last decade. The idea of hanging out with friends through digital avatars hadn’t been normalized.

But today, millions of people—particularly Gen Zs and Millennials—socialize through Fortnite, Roblox, Minecraft, and other massively multiplayer online games (MMOs). Virtual worlds are becoming part of life; a couple even fell in love through an online game and got married.

One startup building a virtual world for socialization is Magic Unicorn, the maker of Chudo. In Chudo, people create avatars and hang out with friends. It’s a little odd-looking at first, but social-based virtual worlds are earlier on the “normalization curve” than game-based virtual worlds.

As of April, Chudo had 800,000 active users, with the majority coming from Gen Zs (53%) and Millennials (28%).

Education

Online education platforms are making education more accessible and more affordable, but video-based instruction is limiting. Virtual worlds lend themselves to more immersive, interactive remote learning.

Dr. Estelle Codier is a 65-year-old retired nurse. She discovered Second Life back in the 2000s and saw an opportunity to teach real-world skills within the virtual world. Within Second Life, Dr. Codier led students on critical care rounds on virtual patients within a virtual hospital. She later published Teaching Health Care in Virtual Space, a guide to using virtual worlds for education, which includes this image:

Dr. Codier remarks:

At one point, I got really interested in why people were in Second Life. I sometimes ran into people and asked them why they were there. I happened to meet this 22-year-old who was waiting for a heart transplant. In real life, she was a girl lying in bed with her oxygen on. But in Second Life she could fly, she could control how people perceived her, which was not someone who might die…I realized that the role of imagination was as important in learning…It wasn’t an imaginary world, it wasn’t Disney. It was an extension to whom they really were. And that means that the learning taking place in Second Life was not fiction: it was gold.

(Her words remind me of a Black Mirror episode, “San Junipero”, which is set in a simulated reality that the elderly can inhabit after death. The episode is on Netflix and I highly recommend it.)

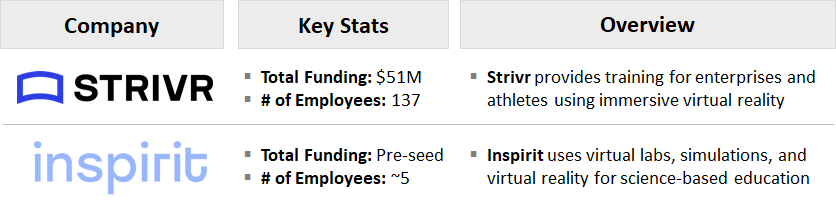

There are companies using virtual worlds for education, including Strivr and Inspirit:

Strivr teaches people critical work tasks using virtual reality. People with dangerous jobs—think operating construction equipment or flying a plane—use Strivr to prepare. NFL athletes also use Strivr for game simulations.

Inspirit is using VR for science education. Its tools replace whiteboards, enabling students to learn in more interactive and immersive environments.

Subscribe to Digital Native to get each week’s piece in your inbox:

Work

The pandemic has caused companies to look for new ways to connect and collaborate remotely, with virtual offices emerging as an alternative to Zoom.

There are a variety of startups in the space; among them:

Features of virtual offices range from the basic (meeting rooms) to the specific (Gather has virtual pool tables for employees to play together). Employees congregate for work and socializing, recreating the feeling of being in the office together.

Startups typically use a mix of digital avatars and virtual reality. Spatial, for example, works with VR headsets and participants take on digital forms within Spatial:

Teeoh, meanwhile, brings users into a digital world with avatars. Teeoh can be used for team meetings or for large professional events and conferences.

Virtual offices often use spatial gaming infrastructure, which allows you to only hear people when they’re nearby—people get quieter as you “walk” away, simulating a real-world office environment.

These companies are a precursor to what’s to come. As teams become more global and distributed—and as Zoom fatigue gets worse—companies will turn to more creative and expressive ways to interact virtually.

Monetizing Virtual Economies

Most of today’s consumer tech giants monetize through ads: Facebook, Google, Twitter, Snap, YouTube. Virtual worlds are the next generation of consumer tech, and they’ll monetize through commerce—through virtual economies and marketplaces.

MMOs already make money this way. A common insult on Fortnite is to call someone “Default”, which means that the person is using free skins (free outfits and weapons). The cool players, meanwhile, pay for exclusive, sought-after skins; buying skins is a way of buying status in the game world.

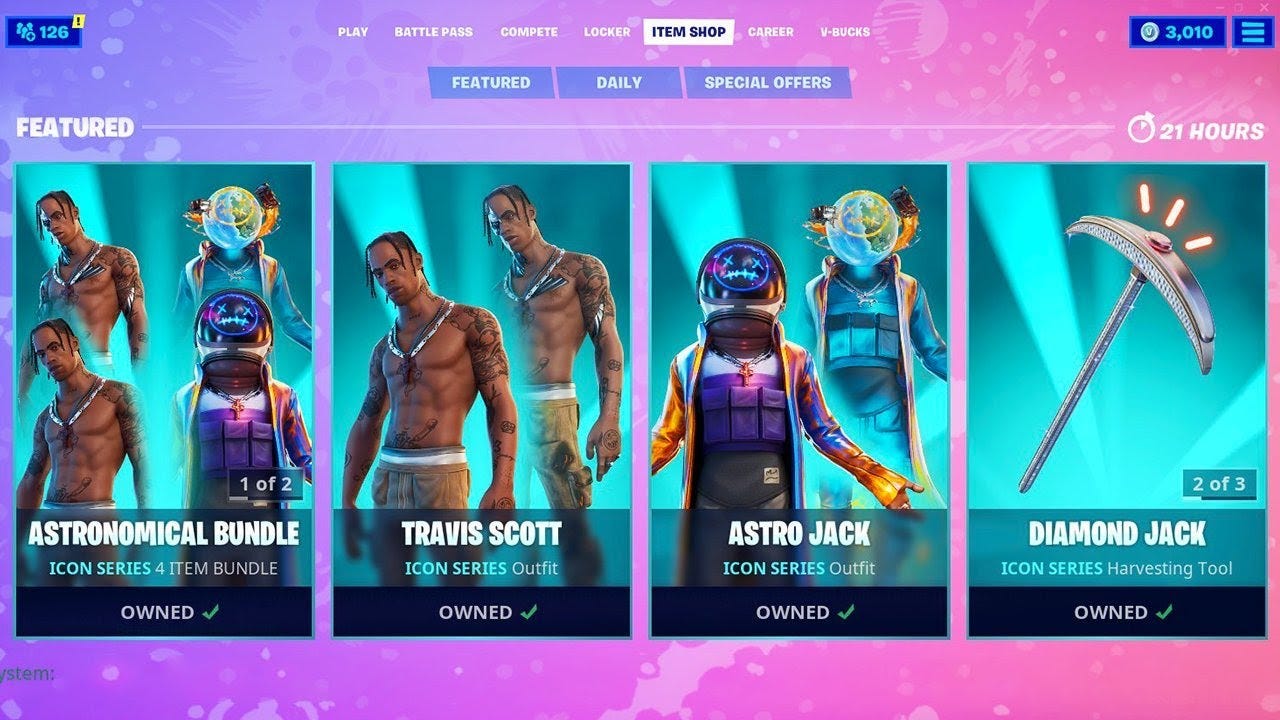

MMOs make about 85% of their revenue from microtransactions. Fortnite, for example, offered Travis Scott skins to align with Scott’s “Astronomical” performance:

Fortnite’s currency is called V-Bucks and can be purchased using real-world money. For reference, the Travis Scott skin costs 1,500 V-Bucks, or about $15. The average paying Fortnite player spends about $20 a month on digital items. Roblox uses Robux as its in-game currency, while Minecraft has Minecraft Coins.

This concept is already moving beyond games. Gucci recently released digital clothing, including a $10,000 virtual dress, and Instagram influencers are using digital clothing to mix up their wardrobes and promote brands.

Marketplaces to facilitate digital commerce will emerge both inside and outside of virtual worlds. G2A and Loot.Farm are formal online exchanges for virtual gaming goods, while unofficial transactions often happen on Discord, Reddit, or eBay. There’s already a black market for goods: in China, Nintendo cracked down on 4,000 Animal Crossing stores that had sprung up on Alibaba’s Taobao.

Blockchain technology will make it easier to trace ownership of digital assets, especially rare or coveted assets. For instance, an avatar of Donald Trump in the game Cryptocelebrities sold for $137,000, tracked by blockchain’s distributed ledger.

Eventually, there will be full-fledged virtual economies within these worlds, for everything from clothes to cars to real estate. Anyone can be an entrepreneur, democratizing access to innovation and opportunity. The virtual hair salon or digital clothing retailer will be the new small business.

Final Thoughts: Blurring Real and Virtual

Today, virtual worlds are microcosms of the physical world. Eventually, the two will bleed into one another. This is already starting to happen:

It’s possible to place a phone call through a digital cell phone in Minecraft, and call someone on their real world phone.

One digital world, Upland, recreates the real world and auctioned off Trump Tower to the highest bidder.

Fittingly, the author of Ready Player One—one of the sci-fi books that popularized the metaverse—is promoting his real-world sequel, Ready Player Two, through a Roblox book tour.

Eventually, virtual worlds will overlay or replicate our physical world. This is similar to the “mirrorworlds” that Snap and Niantic are building, which I wrote about in Snap and Our Augmented Reality Future. People will have their LinkedIn profiles or Facebook profiles or job titles and relationship statuses floating above their heads. You’ll be able to glance across the street and see a restaurant’s menu hovering above the restaurant. VR and AR will coexist, blurring lines between real and virtual.

People have always escaped into other worlds for entertainment—movies, TV shows, video games. Now, people will enter virtual worlds for every part of life. You’ll attend a virtual concert in Wave. Your kids will learn through Inspirit. You’ll work in Spatial. These worlds will be stitched together by indexes like Discord or Bunch or Twitch. Virtual worlds may be the greatest competitive threat for companies as diverse as Facebook, Netflix, and Zoom.

There are opportunities to create companies across virtual worlds. There will be platforms to create the worlds themselves. There will be secondhand marketplaces and exchanges for commerce and ownership. There will be underlying technologies that lower latency and stitch together complicated digital worlds in real time.

In the real world, a new generation of entrepreneurs will enable virtual worlds; within those virtual worlds, a long tail of entrepreneurs will power virtual economies. We’re still years away from the full-on metaverse, but companies are beginning to lay the bricks toward an immersive, virtual future.

Sources & Additional Reading

Check these out for further reading on this subject:

Virtual HQs Race to Win Remote Work | Natasha Mascarenhas, TechCrunch

Video Game Business Meetings | David Segal, NYTimes

The Virtual Economy | Atelier

If you’re interested in these topics, read Matthew Ball’s Metaverse piece, Mario at The Generalist’s Unity S-1 breakdown, or this recent interview with Bessemer’s Ethan Kurzweil, who worked at Second Life

Good write-ups on virtual concerts: Billie Eilish, Lil Nas X, Travis Scott

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive this newsletter in your inbox each week: