The 'Storification' of Technology: From Steve Jobs to Elon Musk, Pixar to FTX

Stories Are Central to Business, But Demand Skepticism and Scrutiny

This is a weekly newsletter about how tech and culture intersect. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Hey Everyone 👋 ,

The year is winding down, and I’m beginning to reflect on what happened in 2022 and where we’ll go in 2023. This week’s piece is the first of a series of “end-of-year” reflections and predictions. In this piece, I’ll tackle one pattern I’ve observed in tech this past year: how storytelling can be a double-edged sword. Then next week, I’ll turn to startup founders, investors, and operators for their end-of-year thoughts.

Let’s jump in.

The 'Storification' of Technology: From Steve Jobs to Elon Musk, Pixar to FTX

One of the qualities that made Steve Jobs a great entrepreneur is that he was an excellent storyteller. Jobs knew how to craft a narrative around a product. Think of his keynote presentations, which were almost cinematic in nature. On stage in 2007, Jobs announced that he’d be introducing three revolutionary new products:

A wide-screen iPod with touch controls,

A revolutionary new phone, and

A breakthrough internet communications device

Then he made his big reveal: these weren’t three distinct products, but rather a single product called iPhone. The audience loved it—and so have consumers. Fifteen years later, Apple has sold 2.2 billion iPhones. iPhone sales alone would place Apple 12th on the Fortune 500—above titans like Microsoft, AT&T, Chevron, Walgreens, and JP Morgan Chase.

Apple has always excelled at storytelling. The company’s 1984 Macintosh commercial remains one of the most iconic ads in history. At the time, the idea of a graphical user interface was groundbreaking. Apple’s Macintosh team came up with concepts like files, folders, and trashcans; created windows for different applications; and decided that tasks could be layered on top of one another. The 1984 commercial reminded consumers how transformative Macintosh was as a product. Macintosh was making computing accessible, charting the course for the next three decades of consumer-facing technology.

Fast forward to 1997, and Apple launched the “Think Different” campaign. Think Different again told a story, this time encouraging consumers to associate Apple products with innovation and creativity.

And a few years later, Apple launched its brilliant iPod ads—still among my favorite all-time ads. They told a new story: one of elegant, simple, portable devices that evoke joy.

Today, Apple is again telling a story—one centered around privacy, which Tim Cook clearly views as the crux of consumer purchase decisions in 2022.

Buoyed by its storytelling prowess, Apple has risen to the top of the business world—its $2.3 trillion market cap is a good $500 billion ahead of 2nd-place Saudi Aramco. Great storytelling can unlock great business performance.

But storytelling can also be dangerous when it goes unchecked.

The Storification of Everything

The literary theorist Peter Brooks warns of a growing trend in American culture: “storification.” In his book Seduced by Story: The Use and Abuse of Narrative, Brooks argues that as a society, we’ve turned to storytelling conventions to make sense of our world, creating a “narrative takeover of reality” that bleeds into every form of communication: the way doctors interact with patients, how financial reports are written, the branding that corporations use to present themselves to consumers.

In The Atlantic, Sophia Stewart takes storification a step further—the internet, she argues, greases the wheels of narrative takeover. On Instagram, we construct stories of our lives that we tell through photo and video. On TikTok, people talk about channeling “main character energy” in their day-to-day. The multi-hyphenate YouTuber and comedian Bo Burnham—an authority on internet culture if there ever was one—puts it this way: “We really do spend so much time building narrative for ourselves, and I sense with people that there was a real pressure to view one’s life as something like a movie.”

We see this same phenomenon taking hold in tech companies and their leaders. Take Elon Musk. Musk is masterful at controlling and burnishing the public persona of Elon Musk. While Musk is no doubt an impressive entrepreneur (though many would be surprised to learn that he isn’t the founder of Tesla, but instead an early investor-turned-CEO), the Musk mythology has gotten ahead of itself. The man was even inspiration for Tony Stark, a.k.a. Iron Man. His every tweet is devoured with such reverence—in an almost Trumpian way— that there’s rarely room for healthy skepticism, scrutiny, or debate. Musk’s accomplishments (and I deeply admire them, particularly SpaceX) should be separate from blind approbation, no questions asked.

Nothing demonstrates the dangers of storification more than the Twitter-Musk saga.

Twitter is a poor business, one that has never figured out how to effectively monetize its influential place in culture. There’s no doubt that Twitter the product is massively important in global communications and news. But Twitter the company has failed to build a robust advertising engine to capitalize on that importance. And it turns out that a text-centric, anger-filled venue might not be the most attractive to advertisers in the first place; the video-centric, joy-filled TikTok fares much better.

Yet Musk’s telling of the Twitter story is quite different. In November, at the Baron Conference in New York, Musk said that Twitter could be the most valuable company in the world. Somehow, a $40 billion company (that would probably be worth $10-15 billion if still publicly-traded) could overtake the aforementioned $2.3 trillion Apple, currently 58x its size. A company with 450 monthly active users—one-seventh as many as Facebook, one-fifth as many as Instagram, and one-third (estimated) as many as TikTok—that is growing its user base just 4% a year could somehow overtake tech giants many multiples bigger. The story just doesn’t make sense.

In his recent piece Narratives, Ben Thompson makes the same point: Musk has his narratives (Bots are bad! Free speech! Subscription is the right business model!) but they come up hollow upon closer examination. Investors backed Musk in his overpriced Twitter acquisition because of Musk’s track record, yes, but also because of the story he told. And it’s looking like they’ll be taking a loss on that investment.

The other major story of the past month—the story of Sam Bankman-Fried and FTX—also underscores the dangers of storification. The complexity and grey areas of FTX’s business was camouflaged by SBF’s simplistic black-and-white narrative. Everyone loves a good hero-villain story, and SBF delivered: SBF, crypto’s young savior, was here to take on the big bad banks and their centralized financial system. He painted the narrative in absolutes, distracting from the conflicts, financial mismanagement, and self-trading under the hood.

We saw the same thing happen with Elizabeth Holmes and Theranos. Holmes told an alluring story—the story of the young wunderkind, complete with lore (green smoothies only) and costume (Steve Jobs-esque black turtleneck). But again, the narrative masked the truth. In his book, Peter Brooks points to Enron and Purdue Pharma as two business examples of “narrative takeover of reality”; FTX and Theranos provide two recent proofpoints in the tech world.

This is difficult, of course, because storytelling is also key to any great entrepreneur and any great company. Storytelling is a powerful tool for attracting talent, motivating employees, and selling to customers.

The challenge is that in today’s fast-paced, internet-fueled environment, we have too often sacrificed analysis, examination, and argument. Any good story should demand a healthy dose of scrutiny; after all, every story is constructed through deliberate choices of inclusion and omission.

As an investor, this discipline is even more critical—how do you separate fact from fiction? What narratives are valid, and what narratives are overinflated and more bluster than substance?

The Glass-Half-Full View

My writing in Digital Native tends to take the optimistic view of technology and entrepreneurship, so I’ll end with a more positive reframing.

The above isn’t to argue that storytelling is bad; rather, stories are an essential part of human connection. One of the reasons I love mediums like film and television is because they leverage stories to influence real-world viewpoints, actions, and policies. Will & Grace was pivotal in driving mainstream acceptance of same-sex marriage in America. Studies have shown that watching a TV show with a female president increases a person’s likelihood of voting for a female president. I dedicated an entire piece to the relationship between media and culture, April’s Cultural Transmission in the Internet Age. From that piece:

Media is also a powerful vehicle for relaying true stories, raising awareness and spurring action. How many Americans would even know about the Rwandan genocide if it weren’t for Hotel Rwanda? Or in the 80s, the excellent film Mississippi Burning painted a vivid portrait of American racism for the movie-going public. And more recently, the Hulu show Dopesick (which I highly recommend) both educated and infuriated viewers about Purdue Pharma and its role in the opioid crisis.

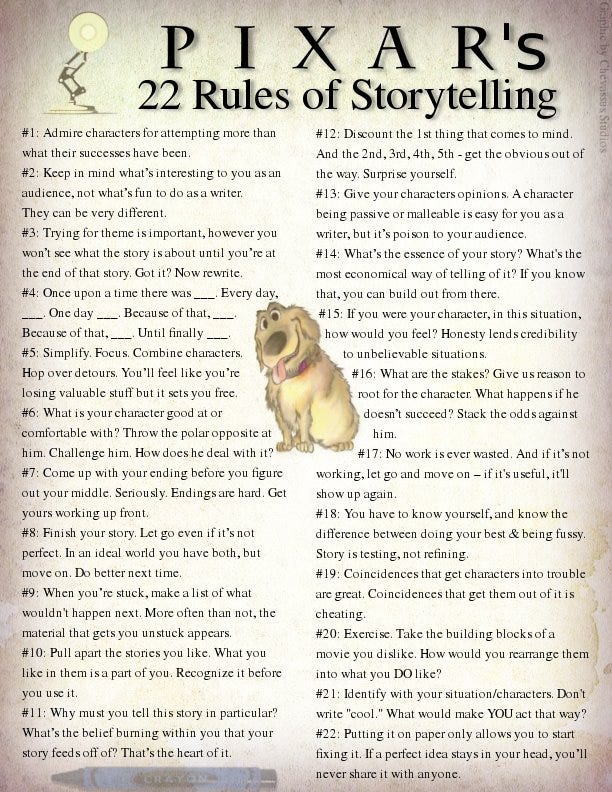

To loop back to Steve Jobs, how many kids (and adults) have learned important life lessons from another of Jobs’s creations—Pixar?

Stories are wonderful, and learning to tell a good story is integral to being successful as an entrepreneur. (Side note: Pixar’s 22 Rules of Storytelling are worth reading in full—they are the masters of their craft.)

The best startups learn to write their own narrative, yet in an honest, high-integrity way. The book Play Bigger calls this “category design”, and when executed well, category design can be powerful.

Qualtrics was a middling survey company until its founders reframed surveys as “Experience Management.” What exec wants to pay for yet another survey tool? No thanks. But the exec who wouldn’t pay for Experience Management? That’s a bad boss right there. Qualtrics’s storytelling was brilliant, inflected the business, and today Qualtrics is a $6B public company (SurveyMonkey, now called Momentive, sits at $1B).

In the bull market of the past decade, it became easy to listen to a good story and to gloss over analysis. After all, everything was up and to the right.

But heading into 2023, and given how narratives seem to have outpaced substance, it’s important to realize what a good story is. A tool in an entrepreneur’s arsenal? Yes. A feather in a company’s cap? Absolutely. But a story isn’t everything. Beware the ‘storification’ of business and technology. Every story demands deep scrutiny and thoughtful examination—especially the good stories. When the story sounds too good to be true, it often is.

Sources & Additional Reading

Seduced By Story | Peter Brooks

Beware the Storification of the Internet | Sophia Stewart, The Atlantic

Narratives | Ben Thompson

Play Bigger | Ramadan, Peterson, Lochhead, Maney

Thank you to my colleague Paris Heymann for being a sparring partner on the topics of storification and category creation, and how they relate to the art of investing and entrepreneurship

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: