The Taxi Cab Theory of Venture Capital

When Did Contrarian Give Way to Consensus?

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 70,000+ weekly readers by subscribing here:

The Taxi Cab Theory of Venture Capital

“The Taxi Cab Theory” is a theory that stems from Sex and the City. The theory posits that men commit to relationships based on timing, rather than based on a deep, intrinsic connection with a partner.

As Charlotte puts it in Season 3:

“Men are like cabs. When they’re available, their light goes on. They wake up one day and decide they’re ready to settle down, get married, whatever. And the next woman they pick up—boom. They get married.”

Most of us can find kernels of truth here. We have friends who were notorious bachelors (or bachelorettes!) and then boom, they turn ~28, become “serious” about dating, and are soon engaged. Clearly, this isn’t the optimal way to choose a partner. But timing or other incentives (say, pressure from family members or a ticking biological clock) strongly influence decision-making. Cab lights flicker on.

You probably saw this segue coming: we see shades of “The Taxi Cab Theory” in venture capital today. To lightly rewrite Charlotte’s quote above:

“VCs are like cabs. When they need to do a deal, their light goes on. They wake up one day and decide they have to invest in a B2B AI company. And the next half-decent founder that comes along—boom. They get married.”

Clearly, this is a problem. When did conviction give way to consensus? When did incentives get so skewed? When did VCs become a bunch of cab drivers wandering around in the dark? These are questions we’ll explore in this week’s piece.

Why Cab Lights Go On

There are various reasons cab lights come on:

Maybe the investor hasn’t made an investment this year. They’re feeling pressure to maintain target pacing.

Maybe in order to get promoted internally, the investor has to show they can win a “hot” deal.

Maybe everyone else is investing in AI / defense / space tech / [insert your buzzy category], and the investor feels FOMO.

Cab lights can also work the other way around, working against a founder to prevent a deal. Maybe the VC did a deal last week, and they feel they can’t do a deal two weeks in a row; they’d look trigger-happy. Maybe the firm’s managing partner has scar tissue in healthcare, so the VC knows they can’t realistically get the deal over the line. Maybe they just read an article about headwinds in gaming, so they’re not feeling too hot on gaming at the moment. The reasons go on, often far beyond a founder’s control.

Founders should realize: the reason a VC says “no” often has nothing to do with you. (The same concept applies to LPs; one mentor once told me: “Believe the no, not the reason.”)

All reasons ladder up to the same core problem: venture has gravitated away from contrarianism and high-conviction decision-making, moving instead toward risk-aversion and consensus thinking. Today’s market is the most consensus market I’ve ever seen. We see it in the data: in the first half of 2025, according to PitchBook, 64% of U.S. venture funding went to AI startups. No surprise there. What’s unique, though, is just how few companies captured most of that. More than a third of venture dollars went to just five (five!) companies.

We see a similar dynamic play out in the LP landscape: 74% of LP dollars went to the top 30 venture firms last year. As the saying goes, “No one ever got fired for allocating to Andreessen Horowitz.”

Venture is maturing as an asset class: a once-cottage industry is now a $1T+ behemoth. VC assets under management doubled between 2019 and 2024 (in 2021 alone, VC AUM grew from $850B to $1.3T), and assets will grow another 38% over the next five years. This is no longer a fledgling industry.

The resulting problem becomes skewed incentives: Andreessen Horowitz lists 92 people (!) under the “Investor” section on its website. General Catalyst lists 70 investors. How does a firm know who to promote from a small army? It’s hard to measure amorphous things like “conviction-building” or “contrarianism.” It’s easier to measure: “Did we beat Lightspeed on that deal?”, “Did we get into Rippling?”, “Did we get a quick mark-up?” TVPI rules the day when DPI takes years to emerge.

Big venture firms are running the same playbook that private equity ran 15 years ago. Public PE firms include Blackstone, Apollo, TPG, and Carlyle. When you realize these firms trade as a multiple of fee-related earnings (FRE), the incentive becomes obvious: fee accumulation. Here’s Blackstone’s management fee growth over the last decade:

If a16z, GC, etc. have public company aspirations (and they seem to), then they’re in the business of accumulating fees. They’ll have their own versions of the Blackstone chart. And fee accumulation runs orthogonal to venture’s original purpose: risk-taking, high loss ratios relative to other asset classes, and power law returns.

We’re in a Prisoner’s Dilemma where good investors might not want to play the game, but they need to. Quick mark-ups and seeing / winning hot deals drive short-term career progression; by the time your portfolio should be showing DPI, you’ve already made GP based on TVPI and vibes.

Consensus vs. Conviction

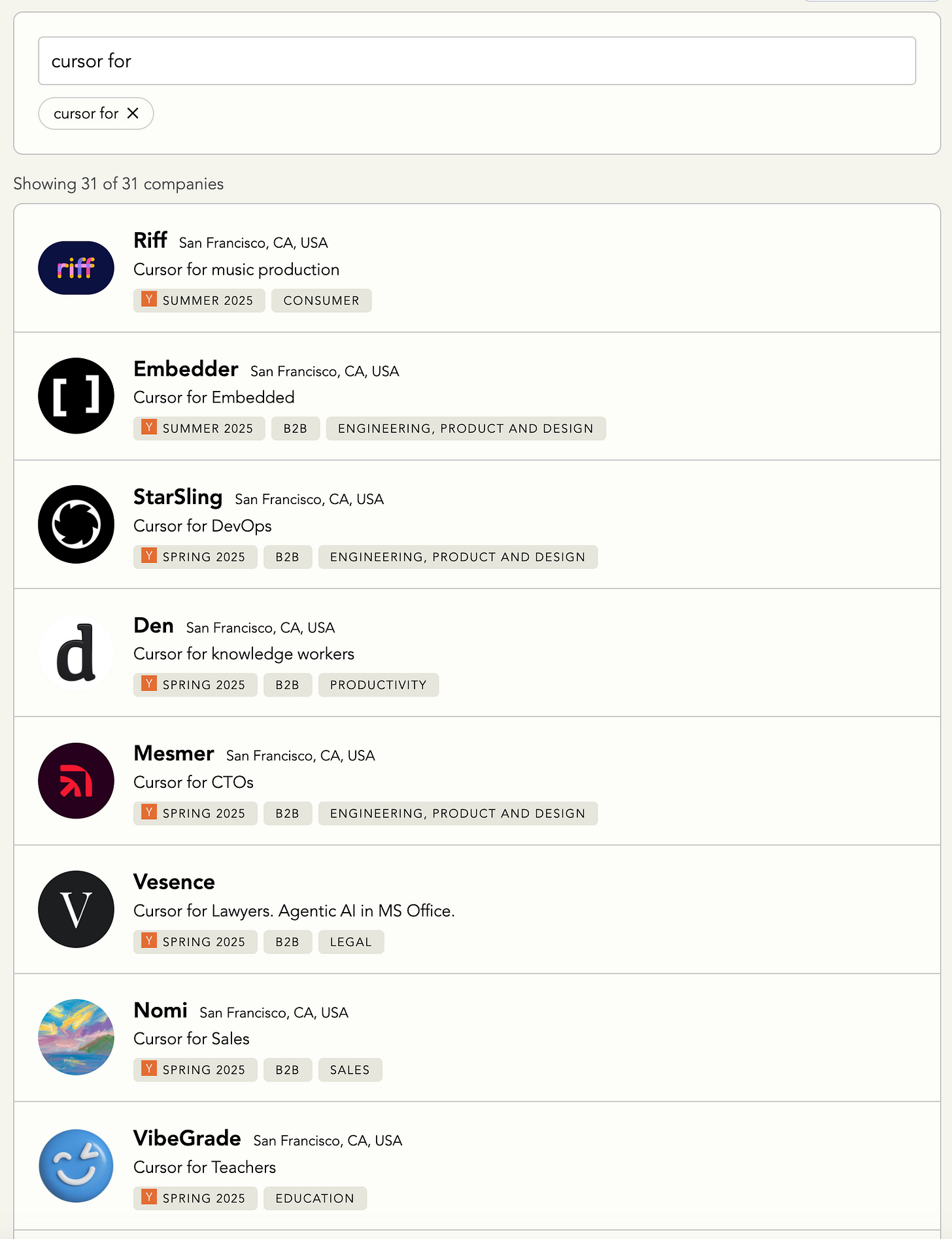

Here’s a surefire way to lose a good venture capitalist’s attention: pitch your company as “____ for X.” A quick search on YC’s database:

31 companies! This isn’t to pick on these companies; I’m sure many are great. But venture is an industry predicated on generational, outlier returns: every good VC wants to be in the company that comes before the x. Founders should pitch something novel, not a formula built on another company’s success.

We’ve see many iterations of this language in Silicon Valley.

“Uber for X” captured the sharing economy of the mid-2010s. We saw variations with Stripe (we’re an API pick and shovel!), Shopify (we’re a platform!), and Figma (real-time collaboration!) over the years. Recent examples I’ve seen include Duolingo, on the back of the company’s ~$17B market cap (often used to refer to any startup that gamifies something), and Anduril for any defense-related startup.

This argument harkens back to last year’s Play It Cool: Chasing Heat vs. Being Contrarian in Venture Capital. That piece included this graphic, inspired by my friends at Founder Collective:

The takeaway was clear: the companies that matter were rarely started when a category was already hot. A few examples:

In 2014, “the sharing economy” was all the rage. The biggest company born that year? Notion. “The future of work” would be trendy a few years later, when most of the key players were already at the growth stage.

In 2015, autonomous vehicles were hot. But the biggest company founded was Scale, an AI “picks and shovels” company way ahead of the AI wave.

In 2016, DTC brands were booming. The highest-valued startup born that year, though, was Anduril, now the poster child of the in-vogue defense space.

And so on, and so on. In venture, when people zig, you should probably zag.

Figma filed its S-1 last week, and the numbers were mighty impressive:

My old firm, Index, led the Seed in Figma and is the largest shareholder today (16.8% for Index, followed by 15.7% for Greylock, 14.0% for Kleiner Perkins, and 8.7% for Sequoia). But Figma wasn’t a clear winner at Index—or in the Valley more broadly—for many years. It took the team four years after founding the company to launch the product. Four years is a lifetime in startups. Dylan and Evan had a clear-eyed view of the future and deep conviction in their product, but the company flew under-the-radar for many years.

The challenge today is that industry incentives work against investments like the Seed in Figma. Incentives encourage quick wins and speed over substance. How many VCs can stomach four years without a product launch? Or moreover, how many firms would allow a portfolio of such long-gestating companies? Systems are no longer set up for patience and conviction.

What Can We Do About It?

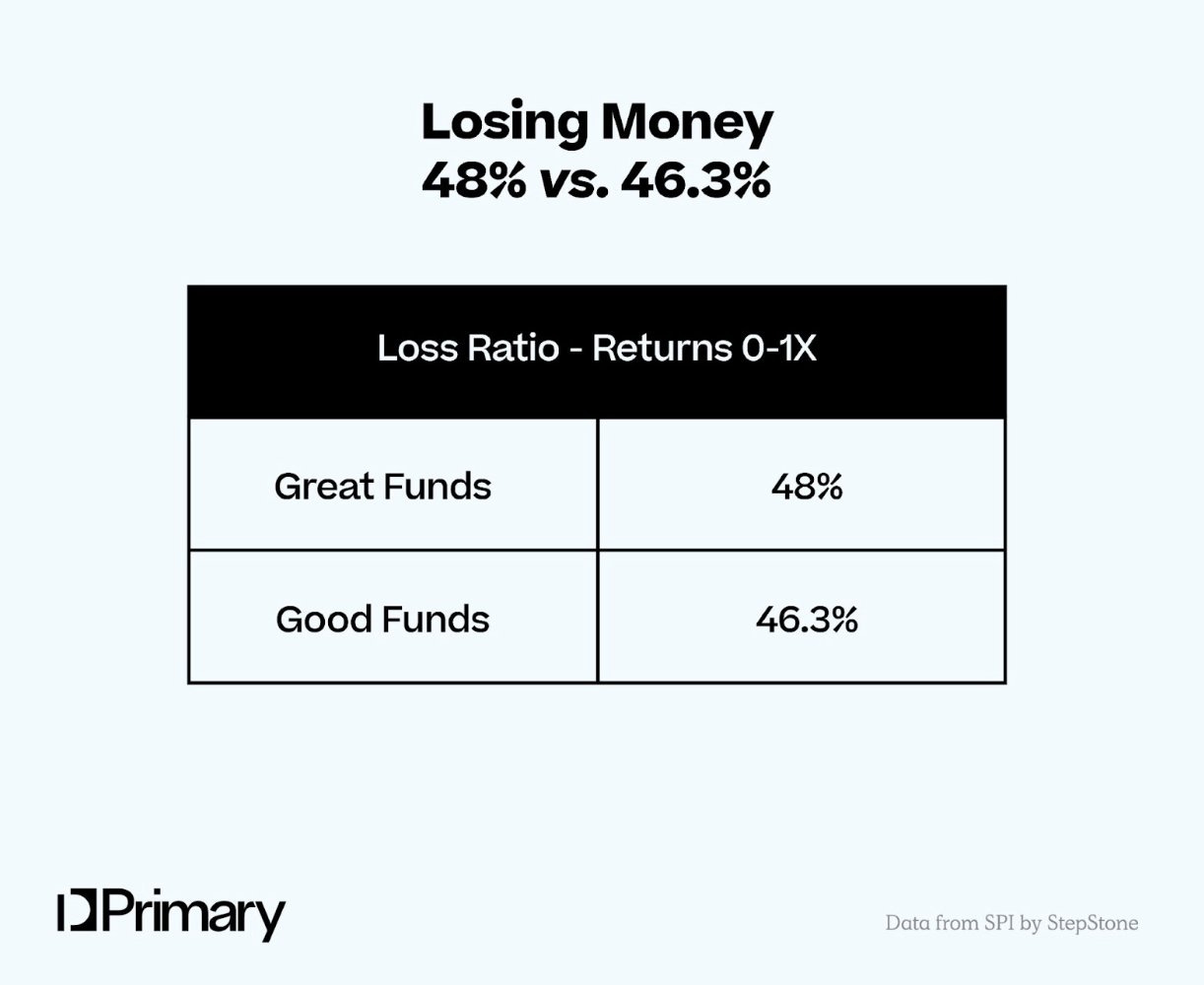

First, we can remember that venture capital is a risk-taking asset class. The best funds have high loss ratios; in fact, many analyses show that “great” funds have higher loss ratios than “good” funds. Here’s some data from StepStone and Primary:

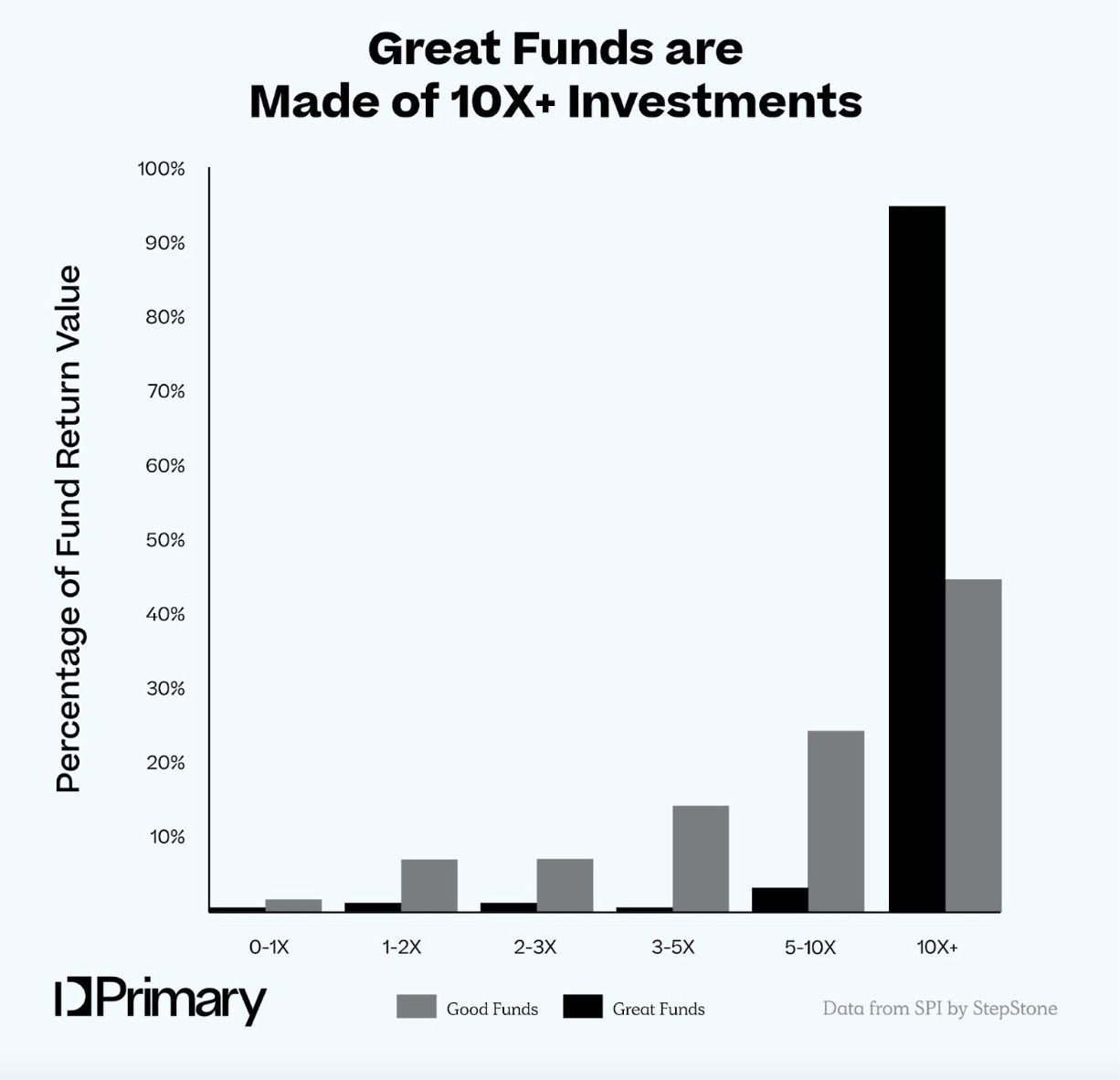

Junior VCs should be encouraged to take risks (primarily at Pre-Seed and Seed, of course, and within reason) to learn the craft. Zeroes should be expected and not punished (again, within reason); not all companies can be winners. Zeroes that could have been fund-returners should be celebrated as good swings: this is a business of home-runs, not second-base hits. More data on that truth here:

This gets to the main point: reward the inputs, not the outputs.

In venture, there’s a time lag. Investors typically need to be promoted before their companies return real dollars. So how can we better measure inputs? Good sourcing and coverage. Good diligence and decision-making. Building deep relationships with founders—and not just winning a competitive deal, but winning a deal that’s unpopular, contrarian, and might not even have anyone else around the table. That’s alpha.

Investors themselves can also take responsibility. We can ask ourselves questions before making investments:

If I did a deal last week, would I still want to do this one?

If no one could find out about this investment for five years, inside my firm or out, would I still want to do it?

Do I have deep conviction, or do I just feel FOMO?

Looking at the table above that showed “hot” categories, you can see the time lag in effect. By the time Figma was ripping, helping make “The Future of Work” buzzy, there were few wall-to-wall products left to build in collaboration software. The category was already saturated. Anduril is consensus now (because defense is hot), but the company was founded a decade ago. Rather than rewarding someone for beating a16z’s American Dynamism team on a defense deal today, we should reward VCs for deep original thinking—finding the next Anduril, in a wildly different, overlooked category.

What could that category be? Maybe longevity. Maybe neurotech, which I’m a huge believer in. Maybe consumer, or climate, or spatial computing. One of my pet peeves is when someone says something like, “But where are the exits in healthcare?” Focusing on the past is a surefire way to be wrong about the future, when variables have shifted that ensure the future ≠ the past. Sure, healthcare hasn’t had many huge exits yet—but I think that by 2030 or 2035, there will have been plenty. That’s one example of many.

All VCs have been guilty of the Taxi Cab Theory, myself included, and it’s tough to resist. Many deals are done not because an investor falls in love with a startup, but because an investor feels pressure or FOMO to do a deal. We’ve all felt that pressure. It takes enormous discipline to forgo the cab light and practice discipline, patience, and quality.

If the venture industry can survive its maturation, everyone needs to be diligent. Smaller funds need to resist playing the game of the asset accumulators, instead remaining focused on conviction over consensus. Firms and LPs need to rewire systems to reward inputs over outputs. And everyone needs to resist becoming a sea of aimless, wandering cab lights chasing mediocre returns.

Any questions on the piece? Chat with my Delphi here:

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: