The Third Workforce: From Analog Labor to Agentic Labor

How do you build for "non-human economic participants"?

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 70,000 weekly readers by subscribing here:

The Third Workforce: From Analog Labor to Agentic Labor

In Blade Runner, Replicants are synthetic beings who perform the work that humans don’t want to. This is mostly work deemed dangerous or undesirable—mining for resources in colonies like Mars, for instance, or serving in the military. (In the opening text crawl of the 1982 film, we’re told that Replicants are “used Off-World as slave labor in hazardous exploration and colonization.”) Occasionally, Replicants are used for pleasure too: companionship, sex work, and so on.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the intersection of technology and work. I see three distinct phases of work:

Phase I: The Analog Workforce (pre-2000s)

Phase II: The Digital Workforce (2000s to early 2020s)

Phase III: The AI Workforce (2020s and beyond)

Phases I and II are both human-centric. But Phase III, which we’re entering, introduces non-human economic participants. What does that mean? In some ways, we’re getting our own Replicants to do the work we don’t want to: so far, mostly mundane, monotonous tasks—but increasingly, cerebral and creative work too.

The focus of this week’s piece is to unpack the three phases above. But first, let’s take a step back.

Goodbye Great Stagnation?

I think we’re about to be shaken out of The Great Stagnation. What’s The Great Stagnation? Simply put, the number of years that it took our global economy to double has shortened rapidly over the last 1,000 years. A millennium ago, it took us 400 years to double. But the world doubled in just 40 years between 1860 to 1900—a 10x improvement.

My friend Michelle Valentine recently wrote about this table, which comes from a 1998 Bradford DeLong paper. If you carry the table forward, you’ll see that the number of years it takes the world economy to double begins to plateau. Economists call this The Great Stagnation:

We’ve been stuck at a ~20 year rate of doubling for almost 100 years. The question is: is this the new normal, or is this a blip in a broader arc of progress?

I think there’s a real possibility that we’ll again re-accelerate GDP growth. We’re in the Wright Brothers era of AI. As Michelle puts it:

The trend is clear: GPT2 in 2019 had an 80% accuracy counting to 10, GPT3 in 2020 had an 80% accuracy in summing three digit numbers, and GPT4 in 2023 passed the California Bar exam. Each 100x increase in compute has unlocked dramatically new capabilities.

Human brains aren’t particularly good at understanding exponential improvements, and no generation of humans has experienced the pace of change that we’re seeing today. The world will look a lot different in 2030.

So how’s work going to change, and what companies will be built?

Phase I: The Analog Workforce

This was physical offices, W-2 employees, punch cards, and desk jobs. Think Working Girl and Office Space.

Each phase of work comes with its own infrastructure. For “The Analog Era,” ADP ran your payroll and QuickBooks did your accounting.

Phase II: The Digital Workforce

In Digital Native, we’ve written extensively about the shift to digital work. This includes shifts in both (1) the types of jobs people have, and (2) the infrastructure underpinning digital work.

To take the first: we’ve seen the rise of internet-native workers. A slew of platforms underpinned this shift in work: YouTube for creators, Roblox for game developers, Fiverr for freelancers, Substack for writers, and so on. When I think “make money online” I think Whop, which is a Swiss Army Knife-like business equipping internet entrepreneurs. You can sell a sneaker bot or launch a paid Discord community using Whop’s tools.

As the workforce digitized, we’ve seen both digital-first jobs and digital-first infrastructure.

The infrastructure for work needed a refresh. Digital work broke down geographic barriers, meaning we needed picks-and-shovels like Deel (which helps you hire across borders) and Anrok (which is led by Michelle Valentine, who I quoted earlier, and which helps you manage sales tax in the age of software). And offline workflows moved online, demanding new tools: Zip for procurement, for instance, or Persona for identity verification and management.

Work became global, fragmented, asynchronous. And digital. No more ADP and QuickBooks; we saw the rise of work infrastructure for an online world.

Phase III: The Agentic Workforce

For the first time, workers don’t need to be human. AI agents can book meetings, run ad campaigns, build software. I like the phrase from earlier—non-human economic participant—because it makes it clear that agents aren’t just digitizing the work, but doing the work (and thereby making money!).

You see a shift in pricing as a result:

This is only the start; we’re already seeing a lot of debate about how to price agents as they replace (or significantly supplement) workers. If everyone becomes a manager of agents—instead of coding yourself, you could essentially supervise five coding agents—how should those agents be priced? One option is as a function of productivity relative to a full-time worker. I doubt we see parity here (if five agents 5x productivity, the company probably won’t be paying five full-time salaries) but I bet we’re not paying per-seat SaaS pricing.

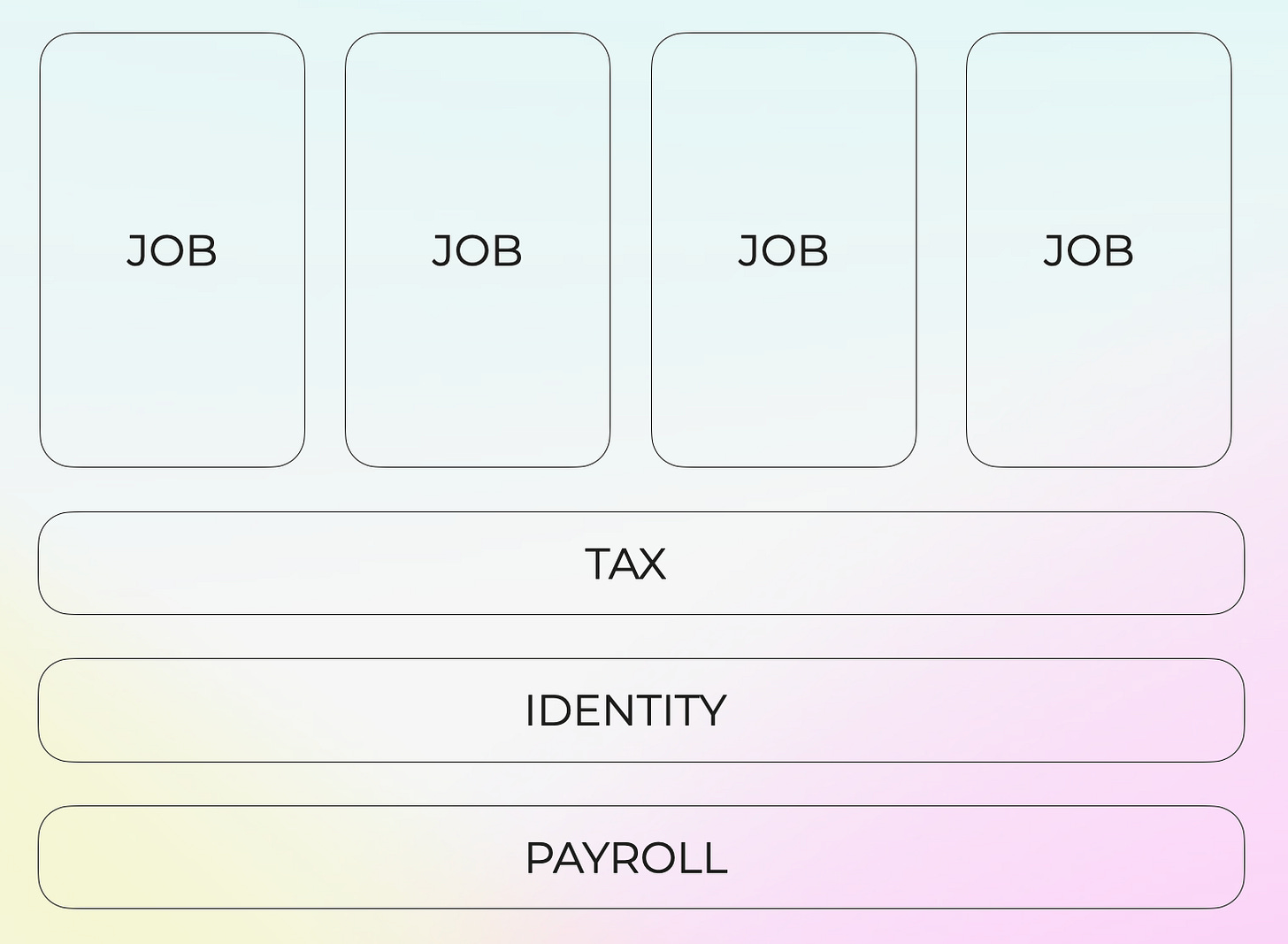

People are naturally spending a lot of time thinking about the agents that do the work. And we should: we’ll see many vertical products, indexed by both function (e.g., customer support) and industry (e.g., construction), as well as some horizontal products. But what about the infra for the agentic workforce? What are the payroll and tax and identity equivalents for agents?

We’re on the cusp of an agentic workforce, and no one really knows how it’ll shake out. Some hot takes / provocative questions:

🔥 Hot Take 1: The IRS will care about AI agents.

In a world where synthetic workers generate real economic value, how do we tax them? It’s been tricky for the IRS to tax Uber drivers and Etsy sellers. But what about when an AI sales rep books $2M this quarter? The tax code wasn’t built for agents without SSNs, bank accounts, or physical locations.

🔥 Hot Take 2: Most SaaS will go obsolete.

Most software is built on the assumption that a human is behind the keyboard—making the purchase decision, drafting the contract, using the software. If a company’s workforce becomes meaningfully AI, how do current SaaS companies fare, companies that were built for legacy payroll, benefits, and compliance systems?

🔥 Hot Take 3: AI agents may one day need labor rights.

This one sounds a bit silly, and it’s a little meta. But if agents are workers, can they be exploited? If agents are generating real economic value, who owns their output? I highly recommend the show Pantheon on Netflix, which explores the premise of artificial intelligences being exploited for profit by corporations (think: hedge funds using agents for highly-profitable trades) and the ethics behind AI exploitation. If you like a slick Black Mirror-esque thriller that makes you think, Pantheon is for you.

🔥 Hot Take 4: Agents will be blamed (often) for decisions.

First they came for our tasks, and I did not speak out. Then they came for our workflows, and I did not speak out. Then they came for our decisions, and I did not speak out… Clearly, automation has moved from tasks → workflows → decisions. Software is now making decisions, and this will inevitably end in many enormous disasters (some agent decision that shuts down a company’s systems or loses the company a ton of money). Agent-makers (the developers) and agent-handlers (the customers) will play the blame game.

🔥 Hot Take 5: Agent-to-agent (A2A?) transactions are coming.

Imagine: your sales team is AI. And the buyer’s procurement team is also AI. The agents discuss and strike a deal. This is A2A—the new B2B?—and my brain is already hurting thinking through the complexities of managing this form of commerce.

Final Thoughts

Obviously tariffs are a reminder that our economy isn’t all digital: we live in the cold, cruel world of atoms. I don’t remember much from my econ classes but I do remember that free trade is sort of… the entire premise of economic growth? Something something comparative advantage.

Of course, the lines are blurring between physical commerce and digital commerce. Savvy companies tie both together. Anrok last week launched support for physical goods tax compliance. Deel certainly helps you hire in-office workers and remote workers. And Persona works as well for verifying you’re 21+ when ordering alcohol on a food delivery app as it does when logging into your crypto wallet. The world is both atoms and bits, and best-in-class software companies underpin both.

But the bits side of that equation is getting a lot more complicated. Already, AI is a co-pilot for most forms of work. I can paste this essay into ChatGPT and get a summary table within seconds:

I can quickly spin up cover art in Midjourney:

But most AI tools still have the human in the driver seat. That will change quickly, and our interactions will change as a result. “Want to grab dinner? Have your agent talk to my agent!” The entire economy of work is about to change.

Sources & Additional Reading:

Read some of Michelle at Anrok’s writing — The Fog of AI and Agentic Framework. Thank you, Michelle, for being a thought partner on this topic!

I liked Konstantine at Sequoia’s Usage Is the Moat about why AI usage data is so critical

Related Digital Native Pieces:

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: