Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 55,000+ weekly readers by subscribing here:

The Three C's: Creativity, Collaboration, and Communication

There are two quotes that I think of often; neither has aged well in our modern era of technology. The first comes from Paul Krugman, the Nobel Prize-winning economist. Poor Paul has been living this one down for 26 years.

The 1998 quote:

“The growth of the Internet will slow drastically, as the flaw in ‘Metcalfe’s law’—which states that the number of potential connections in a network is proportional to the square of the number of participants—becomes apparent: most people have nothing to say to each other! By 2005 or so, it will become clear that the Internet’s impact on the economy has been no greater than the fax machine’s.”

🤦🏼♂️

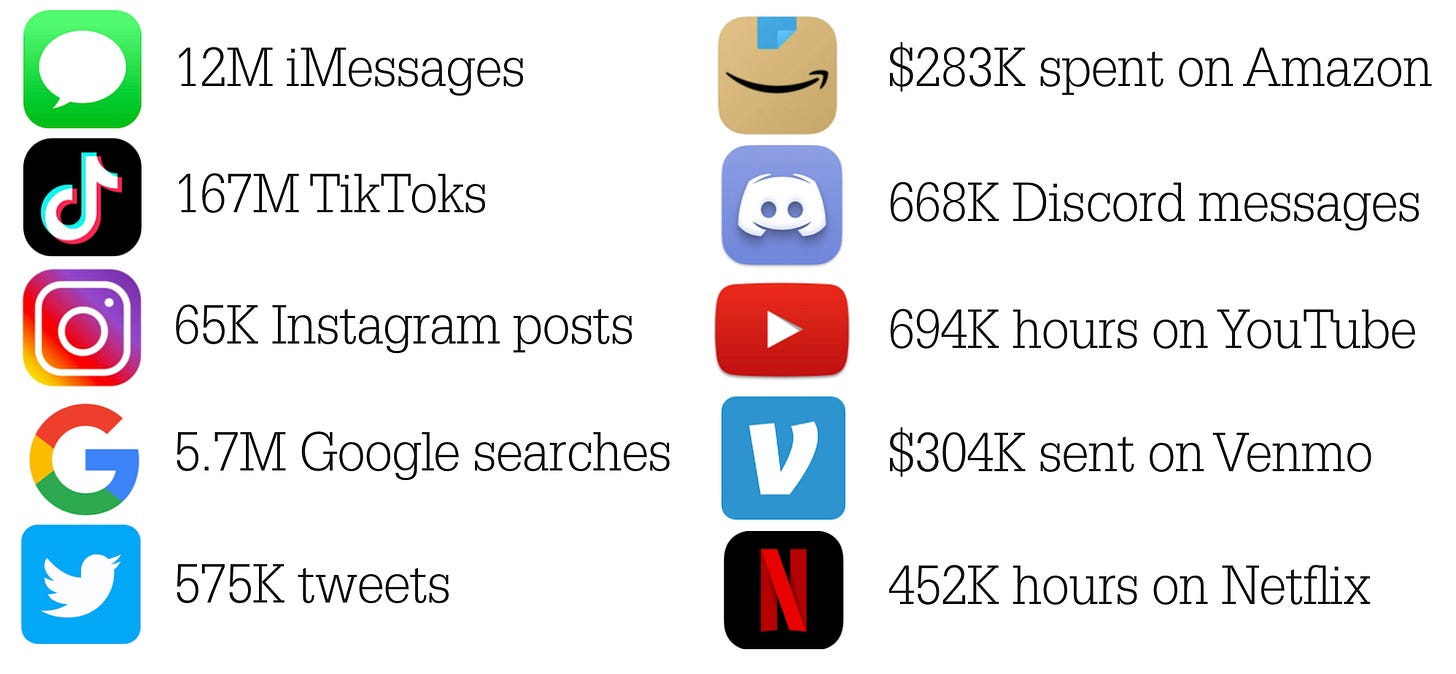

I respect the confidence in Krugman’s prediction; most people don’t have the courage to make big declarations like that. But, of course, it turned out that humans have a lot to say to each other. In a single “internet minute”, we send 12M iMessages, 575K tweets, and 668K Discord messages.

The second quote comes from Barry Diller. In a 2005 interview with WIRED magazine, Barry Diller weighed in on the future of media:

“There is not that much talent in the world. There are very few people in very few closets in very few rooms that are really talented and can’t get out. People with talent and expertise at making entertainment products are not going to be displaced by 1,800 people coming up with their videos that they think are going to have an appeal.”

Again, 🤦🏼♂️.

Diller has had an illustrious career in both old-world media (CEO of both Paramount and 20th Century Fox) and the internet age (founder of IAC, the holding company behind Expedia, Tinder, etc.). But you’d be hard-pressed to find a statement that proved more wrong—other than Krugman’s. The same year that Diller gave that interview, YouTube was founded; Instagram, Twitter, and TikTok soon followed. It turned out that there was a lot of talent in the world—many people in many closets in many rooms. The internet just needed to unlock it.

I imagine you’ll soon be able to add a third quote to this mix, one about remote work. Many people said that companies would never be able to succeed with remote teams; companies like GitLab—fully-remote from the start—have already proved them wrong. I can’t find a quote quite as damning as the two above—the closest is Elon Musk calling remote work “morally wrong”—but I’m sure there are many proclamations that won’t age well over the next decade.

These three quotes touch on three subjects: communication (Krugman), creativity (Diller), and collaboration (remote work). Because everyone loves alliteration—and because I’m a VC who loves a forced framework—we’ll call these the three C’s.

A broad trend-line with technology has been “un-gating” each of the three C’s. Internet and software products have made us 1) talk to each other a lot more, 2) make more stuff, and 3) work together in new ways.

This trend-line won’t stop. In my mind, the amount that humans will communicate, create, and collaborate is fairly boundless; technology is the limiting variable. As technology continues to be a facilitator, we’ll get more of each.

This week’s piece digs into how AI will forward that trend-line, accelerating each C by introducing products that drive more communication, creation, and collaboration.

Creativity

Communication

Collaboration

Creativity

Taylor Swift accounted for 1.8% of all music consumption in the U.S. last year. One out of every 78 songs streamed was a Swift song (for reference, Spotify has over 100M songs), and Swift comprised five of the year’s 10 biggest albums.

2023 Taylor Swift approached 1964 Beatlesmania and 1982 Michael Jackson in terms of cultural juggernaut. Accomplishing such a feat in the modern era—an era in which monoculture has largely died—is astounding.

The reason that culture has fragmented is the explosion of content, made possible by 1) more affordable creative tools, and 2) new distribution channels.

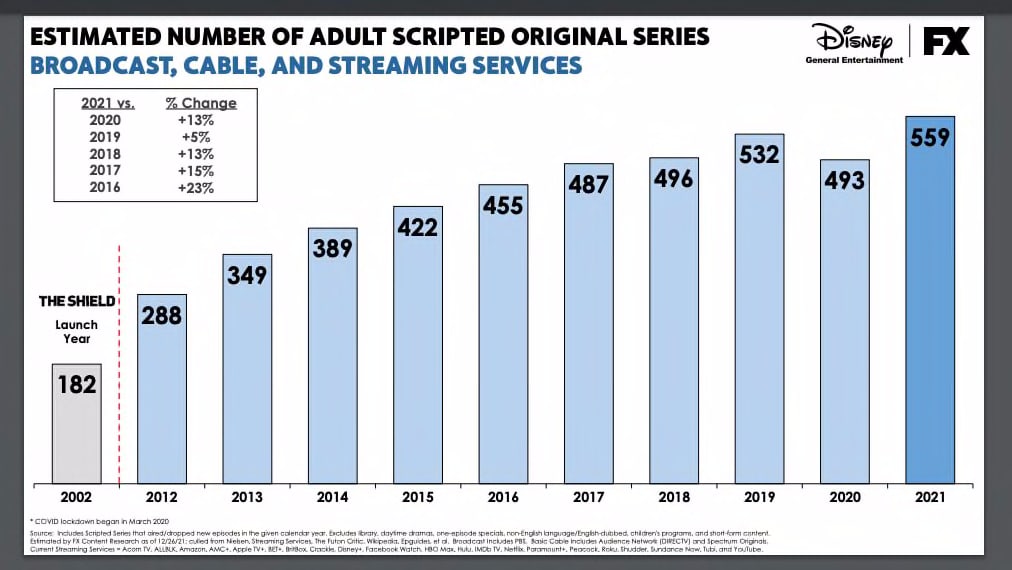

A half-century ago, half of America watched M*A*S*H each week and there were three TV channels. There are now ~600 scripted original series a year, delivered to you via broadcast or cable or streaming or desktop or mobile.

And more young people are watching user-generated content anyway. A new study from Qustodio shows that YouTube is running circles around Netflix among those age 4 through 18.

TikTok in turn is running circles around YouTube in engagement time: that 4-to-18 demo spends an average of 112 minutes per day on TikTok. (I disagree with the study’s classification of TikTok as social media vs. online video, which is why it isn’t in the graphic above.)

It’s difficult to say just how big YouTube is. YouTube has a nice API, but there isn’t a good way to get a reliable size estimate on how many videos are on YouTube. I liked the recent mathematical approach a blogger named Ethan Zuckerman took. He used random URL sampling to back into an estimated number of videos on YouTube, arriving at about 13B. Take a look at YouTube ballooning in video count:

So there’s a lot of content out there.

This is partly because of new distribution channels, like the internet, and partly because of new creative tools. It’s become a lot easier to make good-looking stuff. Back in 2015, Steven Johnson wrote in The New York Times:

The cost of consuming culture may have declined, though not as much as we feared. But the cost of producing it has dropped far more drastically. Authors are writing and publishing novels to a global audience without ever requiring the service of a printing press or an international distributor. For indie filmmakers, a helicopter aerial shot that could cost tens of thousands of dollars a few years ago can now be filmed with a GoPro and a drone for under $1,000; some directors are shooting entire HD-quality films on their iPhones. Apple’s editing software, Final Cut Pro X, costs $299 and has been used to edit Oscar-winning films. A musician running software from Native Instruments can recreate, with astonishing fidelity, the sound of a Steinway grand piano played in a Vienna concert hall, or hundreds of different guitar-amplifier sounds, or the Mellotron proto-synthesizer that the Beatles used on ‘‘Strawberry Fields Forever.’’ These sounds could have cost millions to assemble 15 years ago; today, you can have all of them for a few thousand dollars.

It’s the production of culture that will really change this decade. While the internet was a distribution revolution, generative AI is a production revolution. We think that we’ve seen software make it easier to make stuff, and we have—Unity and Roblox and Canva and so on. But we’re only at the tip of the iceberg. Generative AI is lowering the barrier to creation.

One of my favorite new products is Vizcom.ai, which lets you render your ideas in seconds. Try it out. You can turn a rough sketch of a car into a sleek, stylized SUV:

As AI shows that there’s more latent creativity out there, Barry Diller will continue to live down his words. The last 20 years showed that some people just needed new distribution channels to get noticed; the next 20 will show that some people just need new tools.

Communication

The internet is all about networks, and networks are all about connecting people.

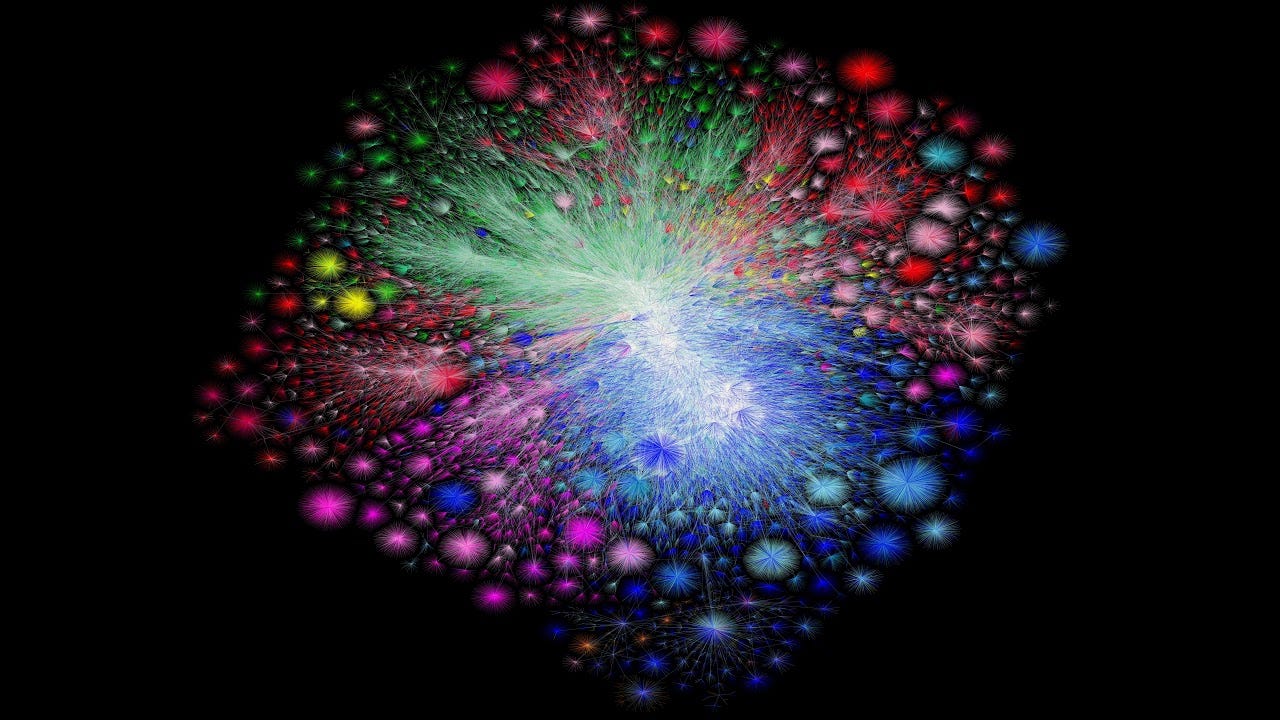

Back in the 2000s, a man named Barrett Lyon sought to visualize the internet’s networks. He used traceroutes (maps of how data travels online from its source to its destination) to create an image that showed internet activity circa 2003:

In 2021, Lyon updated his visualization. This time, rather than using traceroutes, he used Border Gateway Protocol routing tables to get a more accurate view. The updated image is composed of clusters of network regions—examples of clusters include the U.S. Department of Defense’s Non-Classified Internet Protocol Network, Shenzhen Tencent Computer Systems, and Amazon’s AWS. (You can watch a video of the visualization here.)

The internet allowed us to talk to each other—a lot. Expanding on the “internet minute” mentioned earlier, here are some more things that happen in a single minute online:

It’s become second nature to talk to people online—both real-life connections and strangers we meet on the internet. This TikTok comment captures how the app creates a global network built around shared memes:

If the last 20 years were about becoming accustomed to talking to people online, the next 20 will be about becoming accustomed to talking to, well, non-people. AI chatbots that do a good job of acting like people.

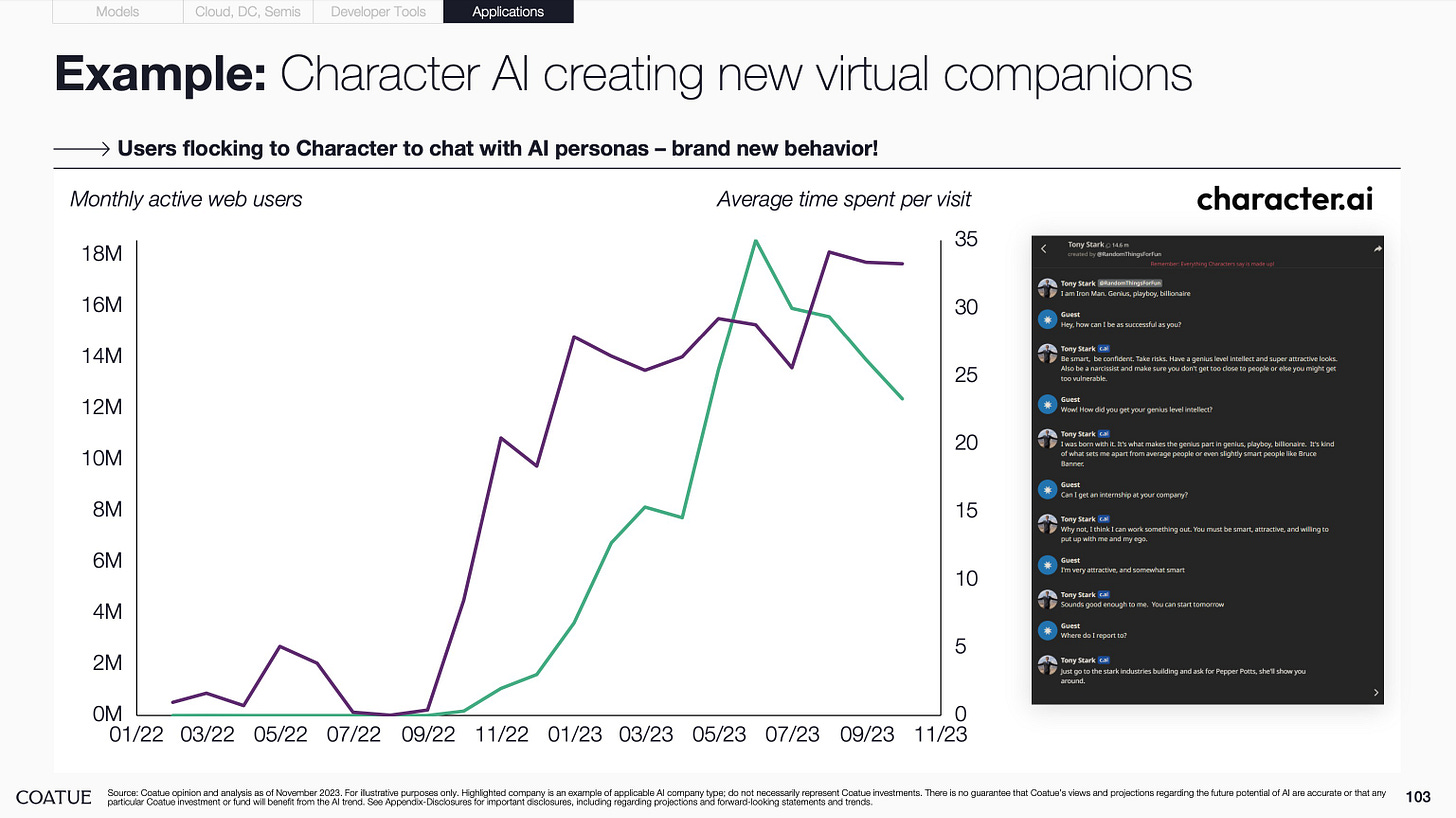

These conversations will take different forms. Some bots will be facsimiles of real-life people: on Character you can chat with Albert Einstein or Napoleon Bonaparte. People seem to like talking to bots—engagement time on Character hovers around 35 minutes per visit, nearing Snap and Instagram levels of engagement:

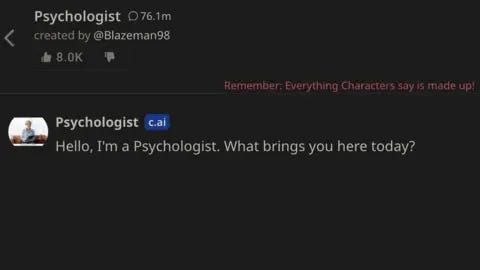

We’re also seeing people enjoy talking to entirely new AI personas. Take another Character example: on the site, a chatbot called Psychologist has become popular among people who can’t afford to see an actual therapist. A user called Blazeman98 created Psychologist a year ago—since then, 78M messages have been shared with the bot.

This is a little dystopian, sure—shouldn’t we, you know, make mental health affordable so that people don’t have to rely on a chatbot? Yes. But I expect this sort of thing will become more common.

Last year we saw chat apps like Replika and Chai blow up (benefiting from NSFW content). When OpenAI opened its app store, AI girlfriends quickly popped up, despite being prohibited. A search in the early days yielded chatbots like “Korean Girlfriend” and “Virtual Sweetheart.”

In the Pre-Seed and Seed markets, I’m seeing chatbots as the early format for AI’s application layer. Use cases are both consumer (“Here’s a friend for you to talk to”) and enterprise (“Here’s a copilot to help you go through legal briefs”). Krugman missed that humans have a lot to say to each other; the internet is teeming with communications flowing back and forth. I expect that humans will also have a lot to say to AIs.

Collaboration

The big shift in work over the past decade was the innovation of real-time collaboration. I’m old enough to remember editing a slide deck, saving the PowerPoint, and emailing it to my colleague for her to take over. (*gasp*) The three words “version control issues” will always create a pit in my stomach.

For years, Microsoft dominated spreadsheets with Excel. Then Google came along with a worse product, Google Sheets, but nailed the one feature that mattered most: real-time collaboration. Figma did something similar in design, catching incumbents and startups alike flat-footed. The same plot-line repeats for most segments of work.

Real-time cloud-based collaboration is now table-stakes. The next innovation is AI—what happens when AI becomes front and center? Last fall’s When AI Begins to Replace Humans explored this question in some detail, asking what it might look like when products are reimagined AI-first.

To continue with the PowerPoint example: PowerPoint has some nifty new tricks, but AI is far from front and center. The startup Tome, meanwhile, is built entirely around AI. I remember Tome’s founder, Keith Peiris, once telling me, “Slide creation and storytelling should be an order of magnitude easier.” AI fulfills that vision. Playing around with making a slide deck in Tome, I can first ask a slide to add an image of a dog:

A few seconds later, I get the output:

A slide later, I can ask for a few bullet points about why AI will change productivity software.

The result:

Microsoft, of course, has now added ChatGPT functionality into its suite of apps, including PowerPoint, Excel, and Word. But the products aren’t designed to be AI-native. AI is tacked on. This creates an Innovator’s Dilemma and an opportunity for startups.

If you look at the way Tome is designed, it’s intuitive—you type in a request. This hints at another change we’ll see. It will soon be standard to have AI coworkers. The result will be a super-charged version of Clippy, the much-memed virtual assistant Microsoft introduced way back in 1997.

We’ll have bots we can talk to and assign work to, just as we do our coworkers. Much of our work will become directing various AI copilots, delegating tasks.

In the past, the analyst might build the financial model and the manager might be tasked with inspecting the analyst’s work for accuracy. What happens when you can give the prompt, “Build an income statement with revenue growing 20% annually for six years, and with 60% gross margins” and generate a model in seconds? The AI becomes the analyst and you become the manager, checking for accuracy. This is oversimplified, of course, but the point stands. More knowledge work will become supervision of AI-executed tasks.

The current trend in collaboration is more collaboration between human colleagues, enabled by software (the slew of $100M+ productivity SaaS companies) and by companies that allow the hiring of global, remote, distributed teams (Deel and Remote, for instance). That trend will continue. Humans will continue to work together more quickly and efficiently, often scattered across time zones. But there will also be a new trend of collaboration with AI, as many of your most valuable coworkers become AI copilots capable of increasingly-complex tasks.

Final Thoughts

When I think of where value accrued over the past 20 years of application-layer technology, I think of products that facilitate communication, creation, and collaboration. These three segments are a good high-level framework for the “jobs to be done” for various products. You have WhatsApp and Instagram and Discord (communication). You have YouTube and Canva and Unity (creation). You have Notion and Miro and Asana (collaboration). The list goes on and on.

I expect that the applications that accrue value in the next 20 years will also fit this mold. Humans still like to do the same things we’ve always liked to do: we like to talk; we like to make stuff; we like to work on stuff together. We’ll continue to flock to products that allow us to do more of each.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: