The Two-Way Mirror of Art and Technology

How Tech Innovations Move Culture

This is a weekly newsletter about how people and technology intersect. To receive this newsletter in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

The Two-Way Mirror of Art and Technology

If you poll people on the average length of a song, most people could tell you that a song is around three or four minutes long. But fewer people could tell you why—and it might surprise them to realize that the reason is technological, not artistic.

A century ago, the vinyl record was created. One of the earliest records was called a “78” because the record spun at 78 revolutions per minute. This technology limited the length of songs, because only so much music could fit onto one disc. A 10-inch 78 could hold three minutes of music, and a 12-inch 78 could hold four minutes. This technology constraint is why—for the last 100 years—song lengths have hovered around three to four minutes.

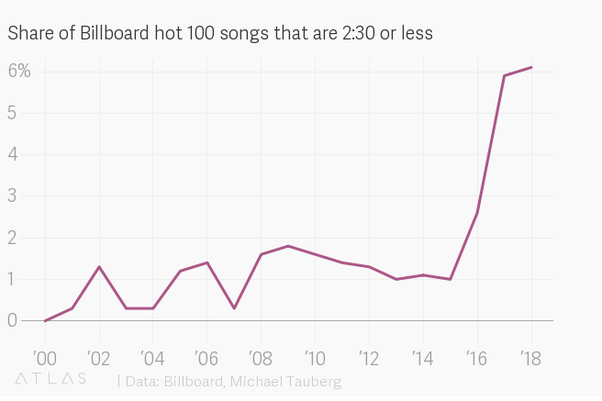

In the last 15 years, we’ve seen the birth of a new music technology: streaming. This breakthrough has similarly influenced art. Streaming economics dictate that artists get paid by the stream, creating an incentive for artists to release shorter songs. Consequently, in the last few years there’s been a sharp uptick in shorter songs:

Artists also only get paid if a listener streams their song for at least 30 seconds. This has had the effect of pulling choruses earlier in songs. Traditionally, a chorus might start 40 seconds into a song; today, it’s not uncommon to hear the chorus in the first 30 seconds.

Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road”, the longest-running #1 hit in Billboard history, is a good example of both these phenomena. The original song clocks in at only 1:53, and the chorus hits just 13 seconds into the song.

Technology informs art, and art informs technology. The two are inseparable and interconnected. This week, I want to look at how technologies over the years have influenced art and culture. I’ll do this by looking at how defining figures of different eras were enabled by new technologies.

📻 Radio

Even before running for president, FDR used radio to host monthly chats with constituents while governor of New York. Eleanor Roosevelt remembered, “His voice lent itself remarkably to the radio.”

In 1933—FDR’s first year in the White House—a listener from California wrote, “Your voice radiates so much human sympathy and tenderness, and Oh, how the public does love that.”

FDR’s first public broadcast as president came on March 12, 1933. The nation was entering the fourth year of the Great Depression, the stock market had fallen 75%, and one in four Americans was unemployed. FDR addressed 60 million listeners in a 13-minute speech at 10pm ET. Many listeners huddled around radios in their living rooms. Movie theaters halted screenings and switched over to Roosevelt’s radio broadcast, resuming films once he’d finished.

FDR used his calm, steady voice to put the American people at ease. His timing was strategic: the day after his broadcast, banks were set to reopen. In his remarks, FDR said, “I can assure you that it is safer to keep your money in a reopened bank than under the mattress.” It worked. On March 13th, millions of Americans lined up to put their cash back into banks; within two weeks, more than half the funds people had withdrawn during the crisis were back in banks.

FDR’s radio addresses became known as “fireside chats”—and yes, he was actually seated next to a fireplace as he spoke. He wielded radio as a powerful tool, and the technology became key to his success. Crucially, if Roosevelt had come of age during a later era, he may never have been president: few Americans knew that FDR was in a wheelchair and radio let him keep that secret.

📺 Television

Two decades after FDR, another three-letter president used a new technology to fuel his rise. JFK was built for television: his good looks, youth, and charm made TV the ideal medium. Kennedy acknowledged that TV benefited him, writing: “Youth may still be a handicap in the eyes of older politicians, but it is definitely an asset in creating a television image people like and (most difficult of all) remember.”

JFK’s candidacy was perfectly timed: between 1950 and the 1960 Presidential Campaign, TV household penetration leapt from 8% to 88%.

As penetration approached 90%, Kennedy and Nixon squared off in four debates—the first debates to be set on live TV. Where Nixon looked pale and ill, Kennedy looked tan and vibrant. Where Nixon addressed his opponent, Kennedy addressed the camera directly. And where Nixon wore a bland gray suit, Kennedy shined in a crisp blue suit. (Dan Rather remembers, “I had always been told to wear a dark suit on TV.”)

For Americans watching on TV, Kennedy won the debate in a landslide. Interestingly, radio listeners gave the edge to Nixon. But by this point, radio listeners were the minority; millions of Americans watched on TV, and Kennedy essentially secured election victory that night. He would go on to be the first candidate to appear on Late Night television and, five days after taking office, delivered the first live TV press conference.

Just as radio enabled FDR, TV enabled JFK. Two mass-media technologies largely determined two iconic American leaders. And beyond politics, television began to define American culture and the people driving culture. Like JFK, Oprah Winfrey was made for TV.

Oprah’s superpower was her relatability. To learn more about Oprah’s incredible story, I highly recommend listening to the podcast series Making Oprah by WBEZ Chicago or the Oprah episode from Acquired. It becomes clear early in Oprah’s life that she’s special because she can connect deeply with people. Television magnified this ability.

Unlike movies, TV was in the home. For an hour each day, Oprah was in your living room, a member of your family. Acquired recounts an early exchange between Oprah and her producer:

Oprah: You know I’m black?

Producer: Yeah, I can see that.

Oprah: You know I’m overweight?

Producer: So are many Americans.

So are many Americans. Oprah’s producer later told her: “You are America—that’s the whole point.” On TV, Oprah wasn’t playing a role; she was playing herself. The intimacy of the medium made that possible.

Oprah’s first show revealed how different her fame would be from the fame of celebrities from a past era. Here’s her opening monologue:

I’m Oprah Winfrey and welcome to the first national Oprah Winfrey Show! There has been so much hoopla about this premiere show that it’s enough to give a girl hives. I mean I’ve got them right now under my armpits…Now, I don't have a lot of problems in my life. I have to tell you, things are going pretty good for me right now, but two things have bugged me for years. The first, my thighs. The second, my love life.

In her first 30 seconds on air, Oprah was self-effacing, personal, and approachable. Her show was an overnight success, and she’d become arguably the most influential woman in the world. Just as TV magnified JFK’s charisma, TV amplified Oprah’s authenticity.

🎞️ Film

While TV was intimate by nature—in your living room, a hub of family time—film was awe-striking and dramatic. Actors were 30-feet-tall on a screen, literally larger than life. Going to the movies was a destination—an event.

And while you might interact with your favorite TV stars daily, you saw your favorite film star once or twice a year. When you weren’t watching them on screen, you were watching them glide down a red carpet. If Oprah was about relatability, movie stars were about aspiration.

This becomes clear when you look back at movie stars throughout Hollywood history: Marilyn Monroe, Audrey Hepburn, Angelina Jolie. TV stars are often raw and personal. Movie stars are glossy and polished.

This is one reason that movie stars have struggled to adapt to the internet more than their TV counterparts. People like Oprah and Ellen DeGeneres and Jimmy Fallon were already themselves on TV; in some ways, social media is a more expansive and always-on version of TV. The elusiveness of the movie star, meanwhile, rings hollow in the age of social media.

🤳 Social Media

Instagram began as a literal filtered version of reality. That made it the perfect platform for the Kardashians, who themselves project a contrived and curated version of life.

In The Business of Fame, I wrote:

A recurring theme as technology has changed celebrity is that content output goes up and production value goes down. The production value of a Kardashian social media post is orders of magnitude lower than the production value of an episode of The Oprah Winfrey Show. This allows digital influencers like the Kardashians to release content at a faster pace, a continuation of the trend started by the shift from film to TV.

While a movie star like Audrey Hepburn might release two films per year, Oprah averaged 182 episodes per season and Kim K averages 660 Instagram posts per year.

One interesting parallel is how online fame has mimicked offline fame’s progression from aspiration to authenticity. While film stars during the Hollywood Golden Age were inaccessible and elusive, TV stars in the late-20th-Century were approachable and relatable. The same arc has played out with the evolution of social media, from Instagram to TikTok.

Both easy-to-use creator tools and a culture of creation embolden the long tail of creators. Only 1 in ~1,000 YouTube users also produces content, but as many as 4 in 5 TikTok users are also creators. The internet is becoming more participatory and as more people create, the pendulum again swings to relatability. Witness the rise of Charli D’Amelio, your everyday teenager from suburban Connecticut who now boasts 114 million TikTok followers.

Last week, I touched on Alice’s and Faye’s High Tea piece about Victoria Paris, the TikTok creator gaining 16,000 TikTok followers per day by relentlessly sharing her life. Victoria Paris posts up to 80 TikToks each day—adding her to my very-unscientific chart underscores just how prolific modern creators can be.

🚀 The Next Generation

“Traditional” celebrities are adapting their playbooks to compete in the new landscape of creativity. In a recent chat with Ben Thompson, Nathan Hubbard made an interesting observation about Taylor Swift:

[Taylor] is, I think, is looking at the TikTok-ization of the world and seeing that the traditional album cycle or tour cycle that an artist would go on, which was effectively—I’m going to put out an album every two years in Taylor’s case, and I’m going to tour in between it, but they’re going to be periods of time where you don’t hear from me—that doesn’t work anymore in 2021. She has really started to accelerate the volume of content, the frequency with which she puts things out, even if it’s just a bunch of Easter eggs in a tweet, she has really changed the way that she communicates with the fan base to move to an always-on model.

Taylor used to religiously release an album every two years. This week, she had her third #1 album in just eight months. This broke a 54-year-old record held by The Beatles’ (Taylor scored her hat trick in 259 days, beating their 364 days).

Modern creation is always-on and the creators who define the next generation of culture will be the immersive creators. They will glide so effortlessly between the real and digital realms that they’ll nearly always be producing content. Emma Chamberlain is one example of such a creator: there’s rarely a moment in Emma’s life when she’s not filming or livestreaming. The camera is a fluid extension of who she is.

A more extreme example is Ludwig Ahgren, a Twitch streamer who made headlines last week when he completed a 31 day livestream. Ahgren spent many hours sleeping, eating, and lying in bed scrolling his phone while millions of people watched. There was clearly demand for Ahgren’s passive livestreaming: he broke the world-record for highest-number of Twitch subscribers.

Donald Trump, in his own way, could also be described as the immersive creator—nearly always tweeting or making headlines. Part of Trump’s savvy was adapting to the always-on nature of internet creation and exploiting it to his advantage.

New technologies and platforms will continue enabling new types of creators. Clubhouse, for instance, has been a boon to the audio creator. Since the onset of television in the 1950s, creation has largely been video-centric; now, audio creators are again having a moment. As virtual reality and augmented reality take hold, a whole new class of creators will rise alongside the technologies.

As they always have, new technologies will determine new forms of creating. And those forms of creating will determine the people who move culture.

Sources & Additional Reading

How FDR's ‘Fireside Chats’ Helped Calm a Nation in Crisis | History

What JFK Had to Say About TV Politics | Smithsonian

Radio: FDR’s Natural Gift | APM Reports

Oprah | Acquired FM

Making Oprah | WBEZ Chicago

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive this newsletter in your inbox each week: