This Is Water: Revisiting Social Constructs

Exploring the Long-Held Norms Ripe for Change

This is a weekly newsletter about how tech and culture intersect. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

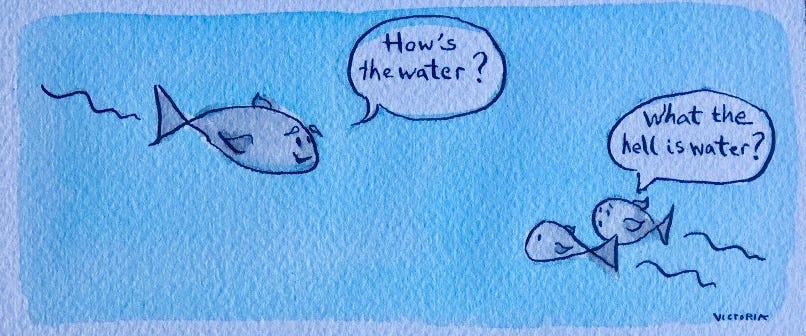

This Is Water

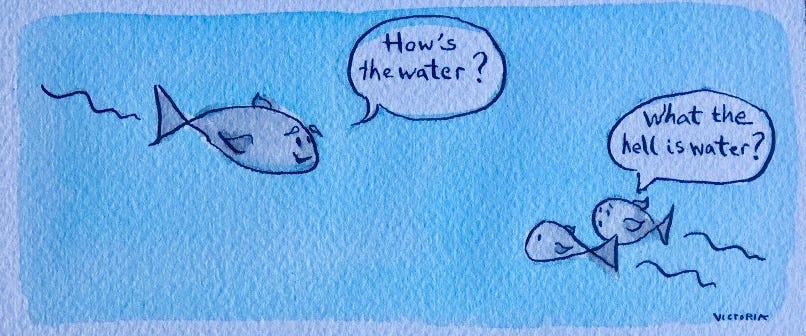

There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says, “Morning, boys. How’s the water?”

And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, “What the hell is water?”

This is the opening story to one of my favorite commencement speeches—David Foster Wallace’s address to the Kenyon College Class of 2005.

Foster Wallace goes on:

This is a standard requirement of U.S. commencement speeches, the deployment of didactic little parable-ish stories. The story thing turns out to be one of the better, less bullshitty conventions of the genre, but if you’re worried that I plan to present myself here as the wise, older fish explaining what water is to you younger fish, please don’t be. I am not the wise old fish.

The point of the fish story is merely that the most obvious, important realities are often the ones that are hardest to see and talk about. Stated as an English sentence, of course, this is just a banal platitude, but the fact is that in the day-to-day trenches of adult existence, banal platitudes can have a life or death importance, or so I wish to suggest to you on this dry and lovely morning.

The most obvious, important realities are often the ones that are hardest to see and talk about.

Many parts of our lives are social constructs. Working in an office. Going to school five days a week. Paying taxes. Marriage.

Gender norms are social constructs—pink, for instance, was originally considered a boy’s color. A 1918 trade publication wrote that, because pink is derived from red, “Pink is for the boys, and blue for the girls. The reason is that pink, being a more decided and stronger color, is more suitable for the boy, while blue, which is more delicate and dainty, is prettier for the girl.”

Only in the 1950s did a series of events shift pink to being “a girl’s color”: Mamie Eisenhower, the newly-minted first lady, wearing a pink ballgown to the inaugural ball; Marilyn Monroe wearing a pink strapless dress in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes; Jackie O wearing a pink Chanel suit the day JFK was assassinated. Slowly, the norm changed.

For added measure on how manufactured gender norms are, here’s a photo of Franklin D. Roosevelt in a dress—a common outfit for boys during his childhood:

Huge swaths of modern life are manmade—simply…made up. Just in the past week, I read three articles that taught me about three surprisingly-recent social creations:

The high five was only invented in 1977. Now it’s so ubiquitous that as I type the words high five, this emoji appears on my MacBook: ✋

The modern use of the word “charisma” only originated in the mid-1900s, and even in 1968, The New York Times still had to explain how to pronounce it: “The big thing in politics these days is charisma, pronounced karizma,” wrote The Times. Now the word is everywhere.

The United States only adopted the five-day workweek in 1932. Our lives now revolve around it. (More on this one later.)

We don’t tend to think about how things came to be the way they are; we just accept them as everyday parts of life. We take things that are made-up (and that may make little sense) as gospel.

This week, I want to dig into the things that we explain away with a wave of the hand and a That’s just the way things are. I’ll examine how these norms might be ripe for change and what companies are leading the way.

Norm: Working in an office

The office is a relatively young concept. And it’s never been a particularly popular one.

In 1822, a man named Charles Lamb was one of the world’s first office employees. In a letter to a friend, he bemoaned his new reality: “You don’t know how wearisome it is to breathe the air of four pent walls, without relief, day after day, all the golden hours of the day between 10 and 4.” He wished for “a few years between the grave and the desk” and then concluded, “but alas, they are the same.” Just a tad bit dramatic.

Over the last 100 years, the office has become a central part of life. The most popular show of this century is literally called The Office. And many modern workers still share Charles Lamb’s 1820s sentiment: I think back to the scene in Office Space where they destroy the printer. (“I’m gonna need those TPS reports ASAP, Peter.”)

But the pandemic dealt the office its most severe blow yet. Over 50% of American office space still sits unoccupied. For many people, remote or hybrid work is the new normal. A recent survey found that 64% of workers would consider quitting if they were required to return to the office full-time.

Some employers are trying to force the world back to the old way of things. Over 1,400 Apple employees recently signed an open letter asking executives to rethink their in-person work mandate, writing: “Stop treating us like school kids who need to be told when to be where and what homework to do.”

Does the pre-pandemic way of things make sense in 2022? No. In the last decade, new tools have made remote and hybrid work not only possible, but efficient and cost-effective. Within the Index portfolio, there’s Slack and Figma and Notion and Dropbox and Pitch. The list goes on. Companies can hire global, distributed teams with Remote. Or companies can recreate their office in Gather, designing a playful virtual space with spatial audio and video. A digital WeWork of sorts, with a much less onerous line item for “rent expense”.

The office isn’t going away completely, of course—there are still benefits to in-person work. An article in The Atlantic this week argues that the office is better for “soft work”—the gossip, eavesdropping, and casual relationship-building that lead to trust and camaraderie among colleagues.

But should knowledge workers do all their work in an office? No. When you start thinking from first principles, it doesn’t make sense: why spend your lunch hour with Janet from accounting when you can eat with your spouse or play with your kids?

When the pandemic began, I said to my partner: the amount of time we’ll get to spend with our kids just went way up. How exciting to be the 30-year-old with years of flexible, remote work ahead; how frustrating to be the 65-year-old who spent the past four decades commuting two hours in traffic every day. (That’s three years of life spent commuting.) Yes, the technology wasn’t there for remote work until recently—but still, this is a definitively positive shift for young workers aspiring to a more flexible and autonomous way of working.

A lot of changes we predicted during COVID didn’t stick. Handshakes are back. Gyms are back. Movie theaters are back, with Spiderman and Top Gun and Minions breaking records. New York City is back, and then some. (Manhattan median rents just hit $4,000 for the first time ever.)

But the old way of working isn’t coming back. It just doesn’t make sense anymore, and it took a massive exogenous shock for us to realize it.

Norm: The 5-day workweek and 2-day weekend

The structure of our workweek is also a relatively new phenomenon.

Back in 1800s Britain, Sundays were a holy day: no one was expected to work Sunday. But people ended up going out drinking, which made Monday mornings not so productive. So factory owners decided to make Saturday a half-day, ensuring workers arrived on Monday well-rested. Eventually, Saturday became a full day off too, and the modern weekend was born. The U.S. officially adopted the five-day workweek in 1932.

In the 1960s, a Senate committee predicted that by 2000, Americans would work a 14-hour workweek thanks to productivity gains. Not so fast. In fact, the average American household works 7-8 working day equivalents in 2022, up from 5-6 in the 1960s.

That said, some startups are experimenting with a 4-day workweek:

But most that have tried it have gone back to the good old five-day workweek.

Our week/weekend norm is so engrained in society that I don’t see it changing. More flexible and freelance work (see below) might change when and where people work, but I expect the workweek structure to remain generally intact.

Norm: Living in one place

Since humans discovered farming 12,000 years ago, most people have pretty much…stayed put. We’re social animals, and we’ve measured our communities in location-based units: households, cul-de-sacs, zip codes, churches.

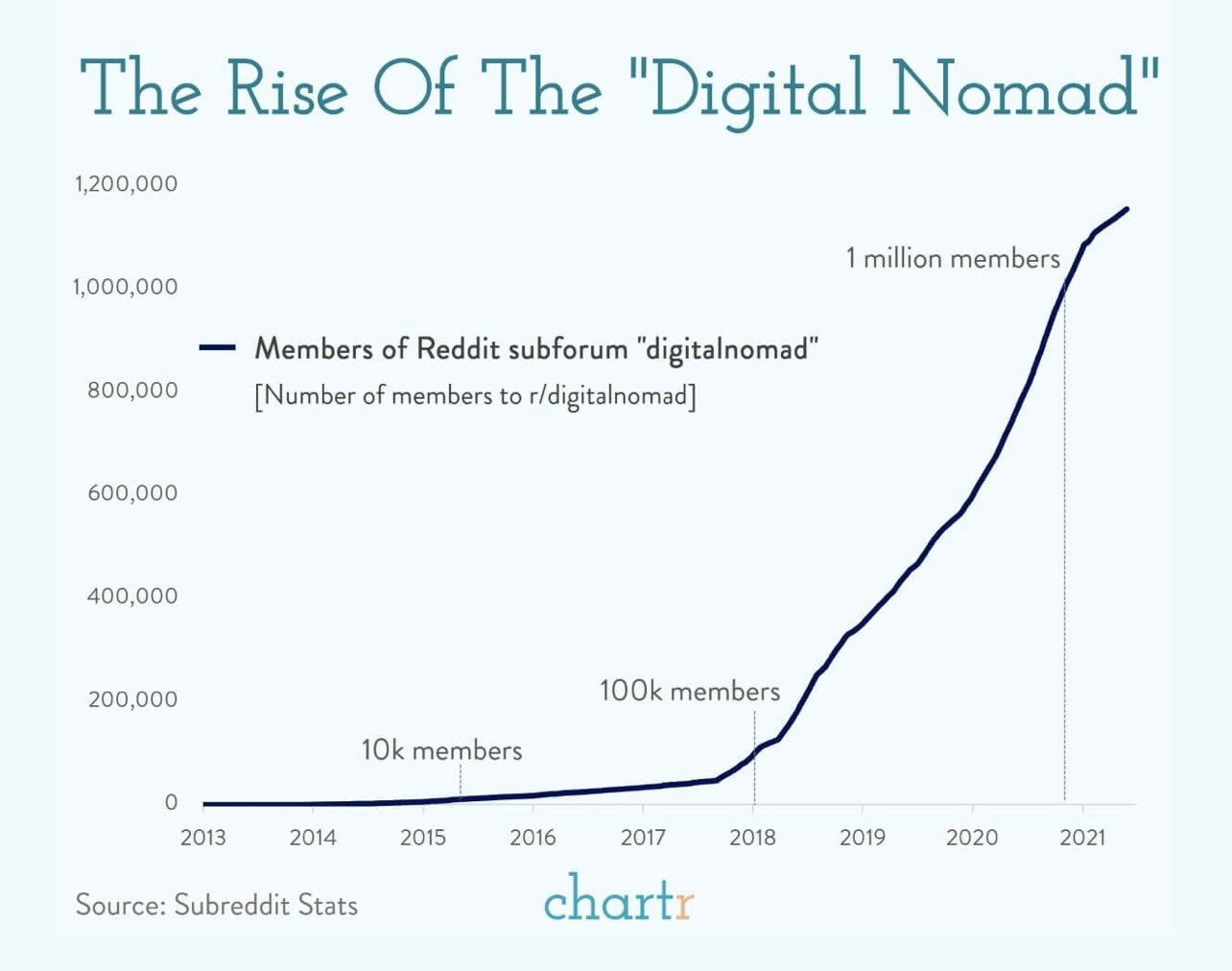

But for many people, that’s starting to change. Millions of people are “digital nomads”, working remotely and traveling the world.

In a world with borderless work—and in a world with borderless friendships born on the internet—does living in just one place make sense?

For many, it still does, but location is becoming more fluid. Airbnb is becoming as much about months-long non-vacation stays as it is about holiday getaways.

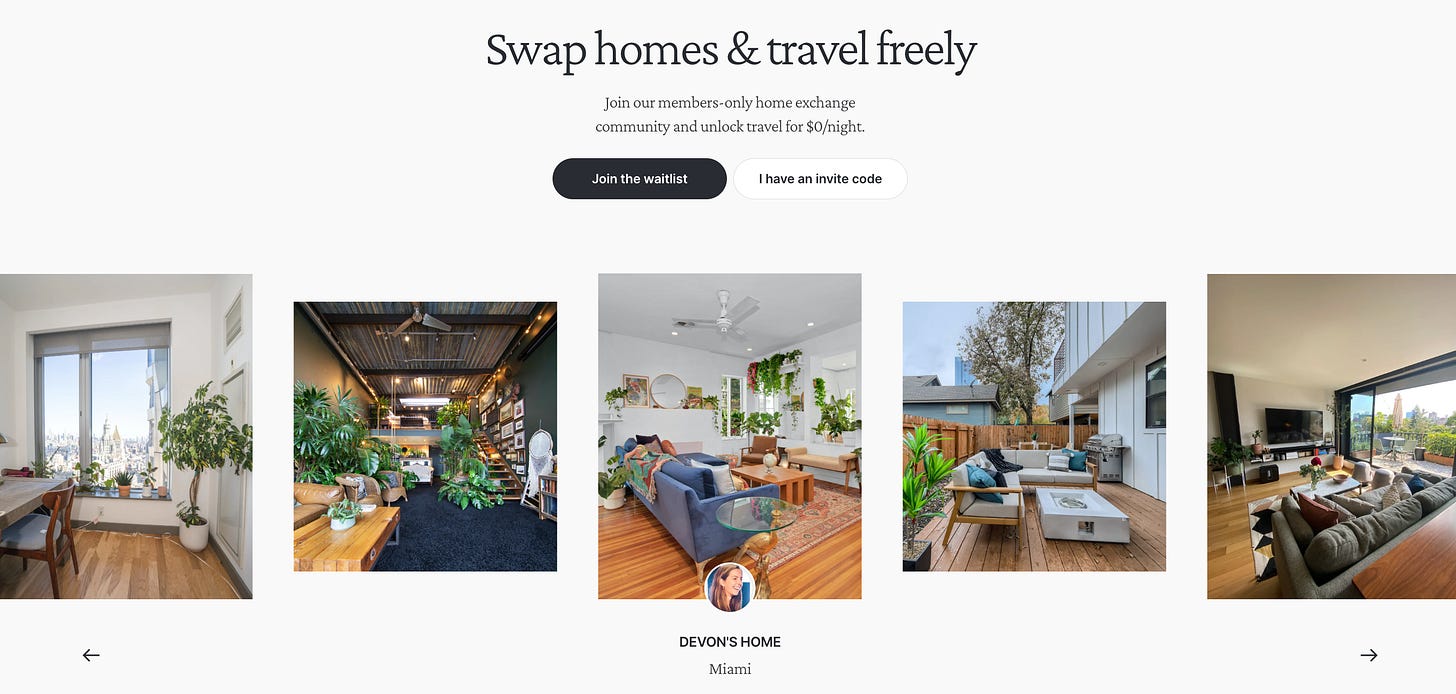

New startups are pioneering new concepts. Kindred lets you swap homes, sort of like Kate Winslet and Cameron Diaz in The Holiday.

Kindred’s vision is to expand the “sharing economy” to everyone, and to make stays away from home more affordable. There’s an interesting ripple effect in the marketplace: if I want to go spend a month in Austin, all of a sudden that opens up a home in New York City (my apartment); if someone wants to come to my place in NYC from LA, all of a sudden their place in LA is available. And so on.

You pay with an annual membership fee, vs. Airbnb’s egregious fees. (Side note: I think Airbnb’s deceptive and sky-high cleaning and service fees pose a serious brand risk to the business—one that the company isn’t taking seriously enough. When you become a meme, it’s rarely a good thing.)

Pacaso makes buying a second home more accessible by letting you buy with a group. A group of friends and I can each pitch in for 1/8th of a ski house in Aspen that Pacaso manages for us.

Summer also helps you buy a second home and rents it for you while you’re away. The goal is to abstract away complexity and make homeownership more affordable.

More and more people will spend some (or all) of the year in a place away from their “main” home—if they even have one. They might stay at an Airbnb or Kindred or Hipcamp, or they might invest in a new home with Pacaso or Summer.

In a technology-driven world, geography no longer rules our lives to the same degree.

Norm: Pursuing your passion

When I think of Gen Z’s approach to work, I think of a line from Ali Wong’s Netflix comedy special Baby Cobra:

Take that, Sheryl Sandberg.

There’s a growing backlash to the Millennial idea that your work should be your purpose in life. Work is shifting lower on Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: work doesn’t need to provide self-actualization; it just needs to provide basic needs like food and shelter. TikTok is full of adolescents proudly slamming their laptops shut at 5pm, despite being in the middle of a Zoom meeting.

One of the best pieces I’ve read in recent months is Anna Codrea-Rado’s long Vice piece called Inside the Online Movement to End Work. The journalist goes deep into r/antiwork, which has become one of Reddit’s most popular subreddits. The antiwork subreddit describes itself as “a subreddit for those who want to end work, are curious about ending work, and want to get the most out of a work-free life.” r/antiwork now has 2.1 million members (who fittingly call themselves “Idlers”), up from just 13,000 in 2019. Comically, the subreddit has three times as many members as r/careerguidance.

Our modern concept of work is actually relatively new—only about 300 years old. For most of human history—from the Greeks, to the Romans, to the Middle Ages—leisure was the basis of culture. Only in the 16th century, when the Reformation brought the rise of the Protestant work ethic, did people begin to see work as a way to bring oneself closer to God. The religious aspect of work faded, but faith in hard work persisted, evolving into the modern-day spirit of capitalism.

There was an excellent piece in The NYTimes last week from Tim Kreider. He captured the exhausted nihilism of a younger generation of workers. Some of my favorite excerpts:

I don’t believe most people are lazy. They would love to be fully, deeply engaged in something worthwhile, something that actually mattered, instead of forfeiting their limited hours on Earth to make a little more money for men they’d rather throw fruit at as they pass by in tumbrels.

I think people are enervated not just by the Sisyphean pointlessness of their individual labors but also by the fact that they’re working in and for a society in which, increasingly, they have zero faith or investment. The future their elders are preparing to bequeath to them is one that reflects the fondest hopes of the same ignorant bigots a lot of them fled their hometowns to escape.

More young people are opting not to have kids not only because they can’t afford them but also because they assume they’ll have only a scorched or sodden wasteland to grow up in. An increasingly popular retirement plan is figuring civilization will collapse before you have to worry about it. I’m not sure anyone’s composed a more eloquent epitaph for the planet than the stand-up comedian Kath Barbadoro, who tweeted: “It’s pretty funny that the world is ending and we all just have to keep going to our little jobs lol.”

I still hope to make it to my grave without ever getting a job job — showing up for eight or more hours a day to a place with fluorescent lighting where I’m expected to feign bushido devotion to a company that could fire me tomorrow and someone’s allowed to yell at you but you’re not allowed to yell back.

Our norm of work-centric life might be short-lived. If the image of 20th-century capitalism was commuting five days a week into Manhattan from Connecticut for your desk job in a midtown skyscraper, the image of 21st-century capitalism might be something quite different: working remotely and freelance for various companies, from various exotic beaches, as you travel the world and enjoy life 🏝. It won’t be that extreme for everyone, of course, but the tide does seem to be turning away from a work-obsessed culture.

Norm: Having one job

Part of that reality will likely be stitching together various income streams. The era of the single job might be over. For most of history, workers have held one profession throughout their careers. People’s names even came from their crafts: Smith for blacksmiths, Taylor for tailors, Webb for weavers, Ward for watchmen. (I can’t seem to recall where Baker, Cook, and Carpenter come from...)

But now, the world is going freelance. In 2027, America will become a freelance-majority workforce. A future “career” might look something like teaching an online course with Reforge, developing Overwolf in-game apps, sprinkling in some brand sponsorships on Instagram, and working a few days a week as a relief veterinary technician through Roo.

You can hire freelancers on companies like Fiverr, Toptal, and Upwork. And a new infrastructure is being built for this world of work. Found, for instance, lets self-employed people manage their banking, bookkeeping, taxes, and invoices.

Having more than one job will be the new normal.

Final Thoughts

I could keep going. The world is changing at an alarming speed, and foundational parts of our everyday lives will soon become extinct. Our kids will ask us why we call charging stations / convenience stores “gas stations”, and we’ll explain to them that cars used to run on gasoline. (*gasp*)

This week’s piece covered many work-related norms: the office, our 5-day workweek, where we live, the careers we pursue. Next week, I’ll do a part 2 that covers norms outside of work, touching on trends like secondhand clothing, plant-based meat alternatives, and the death (or rebirth?) of movie theaters.

I’d also love to include norms ripe for change that I haven’t thought of. Shoot me an email if you’ve thought of one. I’ll share the most interesting submissions next week.

See you next week for part ✌️

This Is Water (Part 2)

Last week in Part 1, I shared the opening parable to David Foster Wallace’s 2005 commencement address at Kenyon College:

There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says, “Morning, boys. How’s the water?”

And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, “What the hell is water?”

The idea is that the most obvious things in the world are often hard for us to see. Many parts of our lives are social constructs—things that are totally…made up. Working in an office. The five-day workweek. Paying taxes. Marriage. Gender.

Sometimes social constructs make sense, and sometimes they don’t. Sometimes they should remain as they are, and other times they’re long overdue for change.

Last week, I dug into norms like working in an office and living in one place. This week, I’ll dig into another set of norms, touching on topics like secondhand fashion, climate change, and movie theaters. The goals are three-fold: 1) to examine the things we take as gospel, 2) to question whether those things are ripe for change, and 3) to explore the companies poised to power that change.

Norm: Driving cars 🚘

Every year, over 40,000 Americans die from car crashes and 2,000,000 more are injured. Cars are the leading cause of death for kids and young adults age 5 to 29. We hurl ourselves through the air in metal death machines, and we think nothing of it.

Meanwhile, our cities are built for cars, not people. The area in New York City devoted to street parking is equivalent to 12 Central Parks (!). Just think how else that space could be used. My partner Martin shared this image with me—once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

Why do we choose to live this way?

In the future, we’ll look back and wonder how we ever centered our lives around cars. Self-driving cars will be so safe that we’ll marvel at the fact that we had vehicles susceptible to human error. Companies like Aurora and Waymo and Applied Intuition will power this future. And cities will become designed for walking and biking and public transit—greener options.

There was an excellent recent piece in The Atlantic about how American cities aren’t built for kids. Essentially, cars lead to urban sprawl, and urban sprawl makes it hard for kids to get anywhere; kids become reliant on their parents to drive them around. Most child socialization happens through unstructured play, which is rarer and rarer for American children given urban sprawl. In Amsterdam, by contrast, the majority of kids bike to school. Higher population density creates a safer environment for unstructured play and, consequently, for human development.

At Index, we’re investors in Cowboy, which makes elegant electric bikes.

This is how our London team gets to work:

My hope is that more of our commutes will soon look like this—especially here in the U.S.

Another major reason cars will decline, of course, is their carbon footprint. The next few norms all build on the theme of climate change.

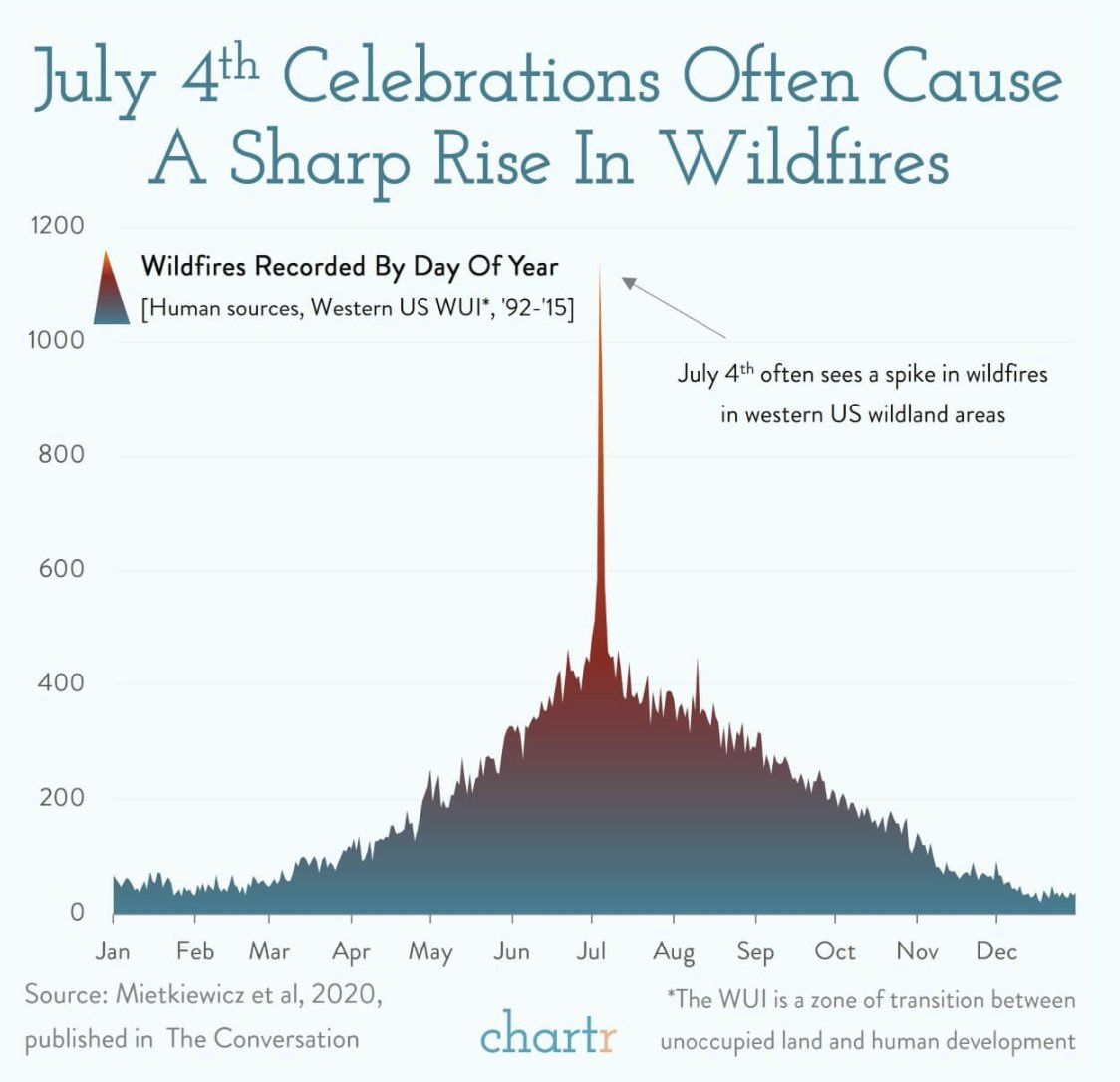

Norm: Fireworks on the Fourth…and other traditions

Climate change may lead us to rethink key parts of culture.

The tradition of setting off fireworks on the Fourth of July began in Philadelphia on July 4, 1777, during the first organized celebration of Independence Day. Fireworks have been a part of all 245 celebrations since. But with climate change wreaking havoc, that might change. Every year, fireworks drive a huge spike in wildfires:

This year, many communities subbed in drones instead.

As climate change worsens, drones may supplant fireworks completely. And other small ways of life may have to adjust for a changing planet.

Norm: Eating meat

Food production is responsible for about 35% of global greenhouse gas emissions, about double the entire emissions of the United States. Meat accounts for 60% of food production emissions.

Young people are eating less and less meat. This chart does a good job showing how habits are changing along generational lines:

To be clear, I don’t think meat is going anywhere. There will still be many meat lovers around in 2050. But plant-based meat alternatives will become a growing share of food. Beyond Meat is already a $2.5 billion market cap public company, though its sales have plateaued in recent quarters. Impossible is becoming a household name.

And there are younger, promising startups building on this behavior shift.

Planted, for instance, is a Swiss company that offers everything from plant-based chicken skewers to plant-based chimichurris.

Simulate is the New York-based holding company behind brands like Nuggs, which offer chicken-less chicken nuggets 🐔

The tailwinds behind meat’s decline are many: some people just want to be healthier; others are fed up with animal cruelty in the meat supply chain; and others care about meat’s carbon footprint. It’ll be interesting to see how large meat alternatives can become. 10% of the meat market? 50%? 90%? The global meat market is growing from $838 billion in 2020 to over $1 trillion by 2025. Even if meat alternatives only capture single-digit percentage points, that’s a multi-billion-dollar opportunity.

Norm: Frequent travel

Given the carbon footprint of air travel, barriers to flying will become higher. The stigma around flying might increase—if you’re a frequent business traveler, or a jet-setting influencer, you may find friends beginning to judge you. Zoom will replace all but the most important business meetings, and job interviews (at least initial screenings) will happen online.

I also expect more people to track and manage their own emissions. Apps like Joro already let you do this:

As climate change ramps up in urgency, more consumers and more businesses will take it upon themselves to take action. Measuring and offsetting our travel might become commonplace.

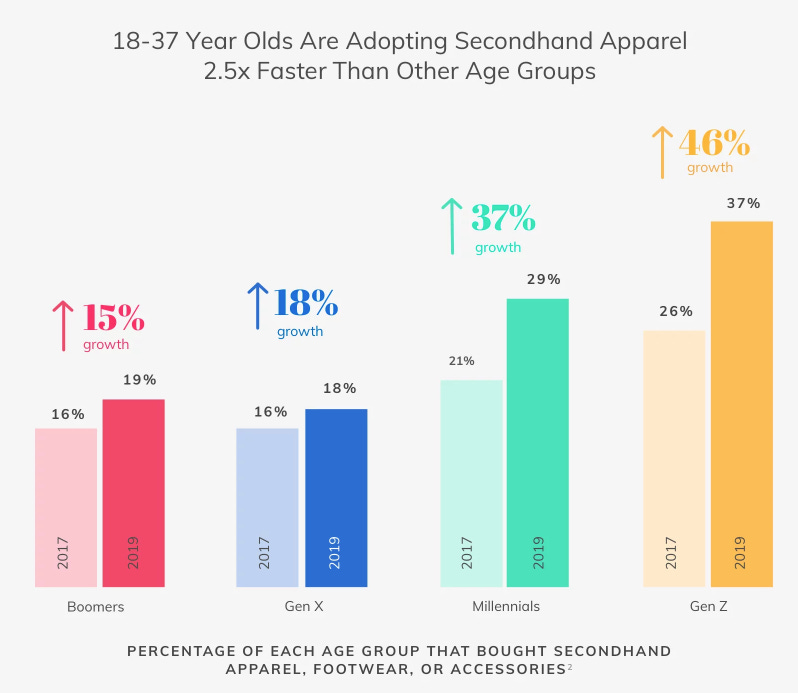

Norm: Buying items firsthand

The last of the climate-related norms:

The fashion industry is responsible for 10% of annual global carbon emissions, with fast fashion the worst culprit of all. Traditionally, buying items firsthand has been our default. But that will change. The secondhand market is booming, buoyed by environmental concerns, and this decade, secondhand will surge past fast fashion in market size.

This shift is generational, with secondhand growing 2.5x faster in younger cohorts than older cohorts.

In the future, your first instinct might not be to shop new goods. You might first peruse Facebook Marketplace or Depop or Vinted. Or you might shop the dedicated “pre-owned” section on brand websites using Reflaunt or Archive. Secondhand will slowly eat the world.

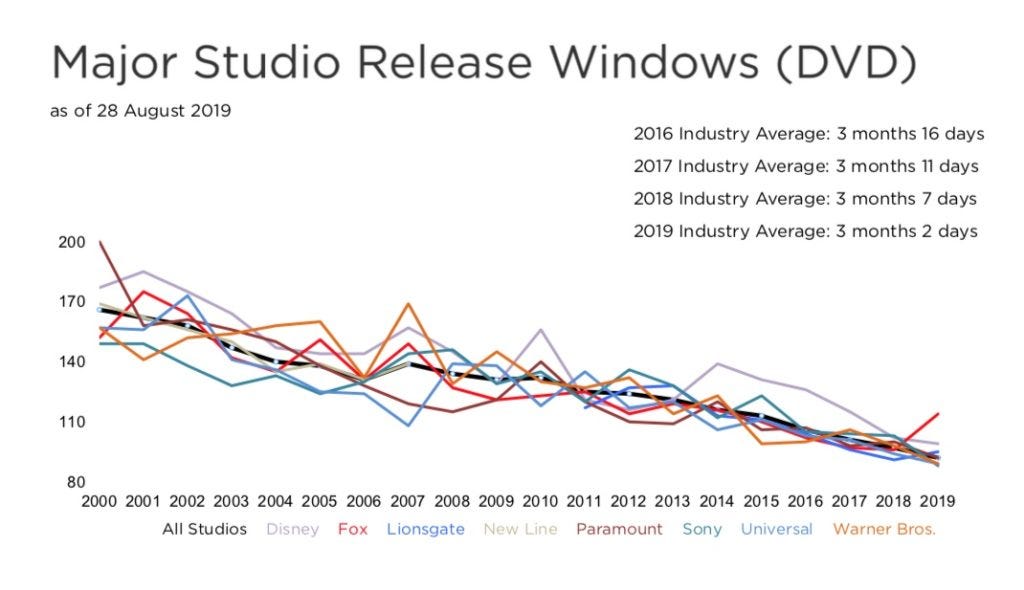

Norm: Movies in theaters for 30+ days

The “theatrical window” is the length of time that movies stay exclusively in theaters. The window used to be 200+ days. Only after those 200 days would movies become available on VHS and DVD. And then, even later on, movies would finally be shown on TV. The idea was that a studio would get paid three separate times: 1) at the box office, 2) from VHS and DVD sales, 3) from selling TV rights. Cha-ching 💰

Even before COVID, the theatrical window was shrinking. Streaming put pressure on old deals struck between theater chains and studios, compressing the window down to ~80 days pre-COVID.

Then COVID hit, and major studios like Warner Bros and Disney began directing major films (Mulan, Borat 2, Hamilton, Soul) straight to streaming.

But in a post-pandemic world, the theatrical window isn’t dead. Blockbusters like Top Gun: Maverick, Spiderman: No Way Home, and Minions: The Rise of Gru have shattered box office records over the past six months. People like the communal experience of moviegoing. But theatrical windows are going to become a lot shorter. The new normal will be a 30- or 45-day window. “Event pictures” will post big numbers at the box office for a few short weeks, before hitting Netflix or Hulu or Disney+.

Meanwhile, family fare (e.g., Pixar films) and lower-budget flicks (e.g., rom coms) will forgo theaters altogether. The economics just won’t make sense anymore.

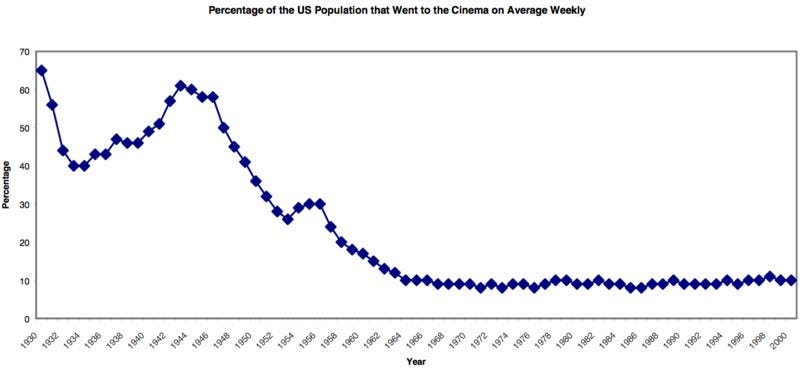

Norm: Only showing movies in theaters

It’s hard to believe now, but there was a time when the average American went to the movie theater 40 times a year (!). Visits to the cinema peaked in the 1940s, just before a little device called a television began to invade American households.

Today, the average person goes to the movies about twice a year. In other words, about 20x less often than 80 years ago.

The big theater chains are, unsurprisingly, struggling. They’re looking for other ways to draw consumers, and many have turned to premium offerings (reclining seats, IMAX, dine-in theaters).

But there’s no reason that cinema real estate should be restricted to showing only movies. Expect to see more content hit theaters. Why wasn’t the Game of Thrones final season shown on big screens across the country? Each episode, brimming with special effects, cost $15 million to make—but viewers had to watch dragons lay siege to entire cities on 60” TVs.

In the future, theaters will become hubs for communal gatherings. The next Stranger Things season. The Super Bowl. The Oscars. Formula 1. The new normal will be that movie theaters become just…community theaters.

Norm: Binge-watching

This is a recent norm: the concept, popularized by Netflix, of consuming a new TV series all at once. Because of Netflix, streaming became synonymous with binge-watching. You burned through 12 hours of House of Cards in a weekend.

But the era of binge-watching is coming to a close. Content budgets are ballooning: Netflix will spend ~$20B on original content in 2022.

It’s unsustainable. Netflix is already finding creative ways to extend the life (and economics) of content. The latest seasons of Ozark and Stranger Things both dropped in two separate segments, months apart. Competing services like Disney+ and Hulu, meanwhile, have stuck to weekly roll-outs for hit shows like The Mandalorian and Only Murders in the Building (both excellent!).

Binge-watching will be remembered as a remnant of the 2010s “peak TV” era—the cash-burning race to win the streaming wars. We’re now going back to the old way of things. One upside: the water cooler might be back, with appointment television creating a more cohesive cultural lingua franca for people to bond over on Monday morning.

Norm: TV and movies as the dominant forms of entertainment

One of my all-time favorite charts is this chart of household technology adoption:

The pink line for color TV is among the most vertical lines on the chart. Within years, 95% of U.S. households had a color TV. And since then, television has dominated entertainment (in tandem with movies, a related phenomenon.) In 2022, American adults will spend three hours a day watching TV. But that figure is actually declining, as TV competes for attention with the internet. Netflix’s Reed Hastings is famous for saying that Fortnite is a bigger competitor than HBO.

Over the coming decades, we’ll see TV and movies stop being the nuclei of culture. There are already 3.5 billion gamers on Earth—about half the planet. And new technologies like virtual reality and augmented reality are only just getting started. The potential for entertainment from these technologies far surpasses what a flat screen can accomplish.

Hollywood has already begun tapping technologies built for non-moviemaking purposes. Disney’s The Mandalorian and live action The Lion King were both rendered with Unreal Engine, the 3D computer graphics game engine from Epic Games (the maker of Fortnite).

Game engines are getting so realistic that they’re able to create unparalleled experiences. Here’s a rendering of the Star Wars planet Tatooine, made with Unreal:

Soon, consumers will be able to walk through this hyper-realistic world. Instead of watching Star Wars at home, you can live it and explore its universe within VR. Television’s command over culture will wane, replaced by new technologies yet to go mainstream—technologies that will gain rapid adoption in U.S. households and will be new additions to the chart above.

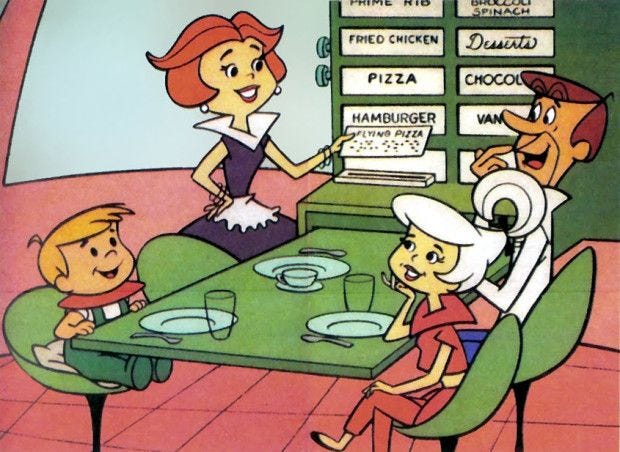

Norm: Stereotypes on gender, race, and nationality

One final, broad norm to end on. As a society, we have a tendency to overestimate technological change and to underestimate social change.

Take The Jetsons. The Jetsons was an animated sitcom in the 1960s about a family living in a futuristic society. The show has flying cars, holograms, and a robotic housekeeper. But Jane Jetson—the matriarch of the family—is a stay-at-home mom whose hobbies include cooking, cleaning, and shopping. Hmm. The creators of The Jetsons could envision a future with incredible inventions, but they couldn’t envision a future with a working mom.

We talk a lot about the technologies that we’ll have by 2030, 2040, 2050. Virtual reality. Self-driving cars. Implants in our brains. Harder to dream up, but arguably more impactful, will be the social changes. We’re already seeing Gen Z be more gender fluid than any other generation. And as the world globalizes—and thanks to the internet—people are becoming more informed about and accepting of other races, ethnicities, and nationalities.

It’s difficult to imagine what the ripple effects will be, but social innovations will likely evolve more rapidly than technological innovations.

It would be easy to keep going. There are many everyday parts of life that our kids will one day laugh at. Paper money will be a distant memory, with dollar bills replaced by software. The digital penetration of money is still in its early innings, but companies like Revolut, Brazil’s Pix, and Cash App (The Rise of Cash App) will change that.

Or our kids might view today’s social media in the way that we view the cigarettes our parents smoked—addictive, unhealthy, destructive to mental health.

When I think of our current trajectory as a digital species, I think of the humans in Wall-E. I think of the oft-told joke: “I’m going to take a break from my mid-sized screen to lie on the couch and watch my big screen while scrolling my small screen.”

My hope is that new generations will challenge this trajectory and right the ship.

But rather than keep going, I’ll finish with interesting submissions from readers who responded to last week’s Part 1.

Reader Submissions

Here are some norms that readers suggested are ripe for change:

“Meetings: more teams will work asynchronously with remote work and distributed, global teams.” — Jeremy

“Alcohol! Gen Z already consumes 20% less alcohol than Millennials. They’re turning to fun alternatives like Ghia, Seedlip, Recess.” — Nora

“Leaving home at 18. We’re already seeing kids stay in the nest longer. The pandemic led to a step-change here, but younger adults are also struggling with finances and will live at home throughout their 20s.” — Gary

“One fixed first name for your entire life. I’m amazed by how many of my Asian friends literally ‘change’ names every other year.” — Kevin

“The duration of formal schooling. Why should schools run 9 months a year? The roots of this system are agrarian, from when there was a summer harvest. The pandemic forced a rethink of how, when, and where students should learn.” — Nora

“Private homes: we might go back to communal living, or multi-generational living.” — Kevin

“Children and schools adapting to digital nomad life. With parents working remotely and changing locations—New York in fall, LA in winter, etc.—will schools follow suit? I could see this happening with private schools for sure.” — Jackie

“My girlfriend and I traveled while working remotely, but it’s still a legal gray area for most countries. Will we see more ‘nomad visas’ as remote work booms? Companies and governments will need to break down international barriers as talent becomes borderless and fluid.” — Jeremy

Final Thoughts

Some of the most successful startups in history were built on behavior changes that challenged a norm: Uber encouraged us to share a vehicle with a stranger; Airbnb asked us to live in a stranger’s home and to invite them into ours; Facebook, and later TikTok to an even greater degree, taught us to broadcast everything to everyone around the world.

It turns out that it doesn’t take as many people to change culture as you might think. My partner Martin shared with me this study on “the 25% tipping point”—basically, research has proved that if just 25% of a population changes behavior, the rest follow suit.

It all starts with awareness of what needs to change. To finish with an excerpt from This Is Water:

It is about the real value of a real education, which has almost nothing to do with knowledge, and everything to do with simple awareness; awareness of what is so real and essential, so hidden in plain sight all around us, all the time, that we have to keep reminding ourselves over and over:

“This is water.”

“This is water.”

It is unimaginably hard to do this, to stay conscious and alive in the adult world day in and day out.

Sources & Additional Reading

This Is Water | David Foster Wallace (I promise, this is the best thing you’ll read this week)

It’s Time to Stop Living the American Scam | Tim Kreider, NYTimes

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: