This Is Water: Revisiting Social Constructs

Exploring the Long-Held Norms Ripe for Change

This is a weekly newsletter about how tech and culture intersect. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

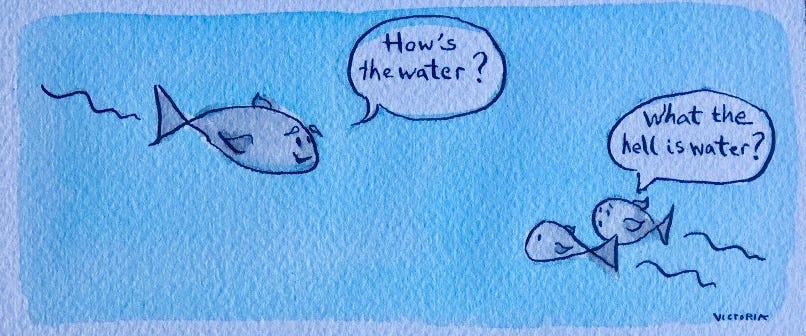

This Is Water

There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says, “Morning, boys. How’s the water?”

And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, “What the hell is water?”

This is the opening story to one of my favorite commencement speeches—David Foster Wallace’s address to the Kenyon College Class of 2005.

Foster Wallace goes on:

This is a standard requirement of U.S. commencement speeches, the deployment of didactic little parable-ish stories. The story thing turns out to be one of the better, less bullshitty conventions of the genre, but if you’re worried that I plan to present myself here as the wise, older fish explaining what water is to you younger fish, please don’t be. I am not the wise old fish.

The point of the fish story is merely that the most obvious, important realities are often the ones that are hardest to see and talk about. Stated as an English sentence, of course, this is just a banal platitude, but the fact is that in the day-to-day trenches of adult existence, banal platitudes can have a life or death importance, or so I wish to suggest to you on this dry and lovely morning.

The most obvious, important realities are often the ones that are hardest to see and talk about.

Many parts of our lives are social constructs. Working in an office. Going to school five days a week. Paying taxes. Marriage.

Gender norms are social constructs—pink, for instance, was originally considered a boy’s color. A 1918 trade publication wrote that, because pink is derived from red, “Pink is for the boys, and blue for the girls. The reason is that pink, being a more decided and stronger color, is more suitable for the boy, while blue, which is more delicate and dainty, is prettier for the girl.”

Only in the 1950s did a series of events shift pink to being “a girl’s color”: Mamie Eisenhower, the newly-minted first lady, wearing a pink ballgown to the inaugural ball; Marilyn Monroe wearing a pink strapless dress in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes; Jackie O wearing a pink Chanel suit the day JFK was assassinated. Slowly, the norm changed.

For added measure on how manufactured gender norms are, here’s a photo of Franklin D. Roosevelt in a dress—a common outfit for boys during his childhood:

Huge swaths of modern life are manmade—simply…made up. Just in the past week, I read three articles that taught me about three surprisingly-recent social creations:

The high five was only invented in 1977. Now it’s so ubiquitous that as I type the words high five, this emoji appears on my MacBook: ✋

The modern use of the word “charisma” only originated in the mid-1900s, and even in 1968, The New York Times still had to explain how to pronounce it: “The big thing in politics these days is charisma, pronounced karizma,” wrote The Times. Now the word is everywhere.

The United States only adopted the five-day workweek in 1932. Our lives now revolve around it. (More on this one later.)

We don’t tend to think about how things came to be the way they are; we just accept them as everyday parts of life. We take things that are made-up (and that may make little sense) as gospel.

This week, I want to dig into the things that we explain away with a wave of the hand and a That’s just the way things are. I’ll examine how these norms might be ripe for change and what companies are leading the way.

Norm: Working in an office

The office is a relatively young concept. And it’s never been a particularly popular one.

In 1822, a man named Charles Lamb was one of the world’s first office employees. In a letter to a friend, he bemoaned his new reality: “You don’t know how wearisome it is to breathe the air of four pent walls, without relief, day after day, all the golden hours of the day between 10 and 4.” He wished for “a few years between the grave and the desk” and then concluded, “but alas, they are the same.” Just a tad bit dramatic.

Over the last 100 years, the office has become a central part of life. The most popular show of this century is literally called The Office. And many modern workers still share Charles Lamb’s 1820s sentiment: I think back to the scene in Office Space where they destroy the printer. (“I’m gonna need those TPS reports ASAP, Peter.”)

But the pandemic dealt the office its most severe blow yet. Over 50% of American office space still sits unoccupied. For many people, remote or hybrid work is the new normal. A recent survey found that 64% of workers would consider quitting if they were required to return to the office full-time.

Some employers are trying to force the world back to the old way of things. Over 1,400 Apple employees recently signed an open letter asking executives to rethink their in-person work mandate, writing: “Stop treating us like school kids who need to be told when to be where and what homework to do.”

Does the pre-pandemic way of things make sense in 2022? No. In the last decade, new tools have made remote and hybrid work not only possible, but efficient and cost-effective. Within the Index portfolio, there’s Slack and Figma and Notion and Dropbox and Pitch. The list goes on. Companies can hire global, distributed teams with Remote. Or companies can recreate their office in Gather, designing a playful virtual space with spatial audio and video. A digital WeWork of sorts, with a much less onerous line item for “rent expense”.

The office isn’t going away completely, of course—there are still benefits to in-person work. An article in The Atlantic this week argues that the office is better for “soft work”—the gossip, eavesdropping, and casual relationship-building that lead to trust and camaraderie among colleagues.

But should knowledge workers do all their work in an office? No. When you start thinking from first principles, it doesn’t make sense: why spend your lunch hour with Janet from accounting when you can eat with your spouse or play with your kids?

When the pandemic began, I said to my partner: the amount of time we’ll get to spend with our kids just went way up. How exciting to be the 30-year-old with years of flexible, remote work ahead; how frustrating to be the 65-year-old who spent the past four decades commuting two hours in traffic every day. (That’s three years of life spent commuting.) Yes, the technology wasn’t there for remote work until recently—but still, this is a definitively positive shift for young workers aspiring to a more flexible and autonomous way of working.

A lot of changes we predicted during COVID didn’t stick. Handshakes are back. Gyms are back. Movie theaters are back, with Spiderman and Top Gun and Minions breaking records. New York City is back, and then some. (Manhattan median rents just hit $4,000 for the first time ever.)

But the old way of working isn’t coming back. It just doesn’t make sense anymore, and it took a massive exogenous shock for us to realize it.

Norm: The 5-day workweek and 2-day weekend

The structure of our workweek is also a relatively new phenomenon.

Back in 1800s Britain, Sundays were a holy day: no one was expected to work Sunday. But people ended up going out drinking, which made Monday mornings not so productive. So factory owners decided to make Saturday a half-day, ensuring workers arrived on Monday well-rested. Eventually, Saturday became a full day off too, and the modern weekend was born. The U.S. officially adopted the five-day workweek in 1932.

In the 1960s, a Senate committee predicted that by 2000, Americans would work a 14-hour workweek thanks to productivity gains. Not so fast. In fact, the average American household works 7-8 working day equivalents in 2022, up from 5-6 in the 1960s.

That said, some startups are experimenting with a 4-day workweek:

But most that have tried it have gone back to the good old five-day workweek.

Our week/weekend norm is so engrained in society that I don’t see it changing. More flexible and freelance work (see below) might change when and where people work, but I expect the workweek structure to remain generally intact.

Norm: Living in one place

Since humans discovered farming 12,000 years ago, most people have pretty much…stayed put. We’re social animals, and we’ve measured our communities in location-based units: households, cul-de-sacs, zip codes, churches.

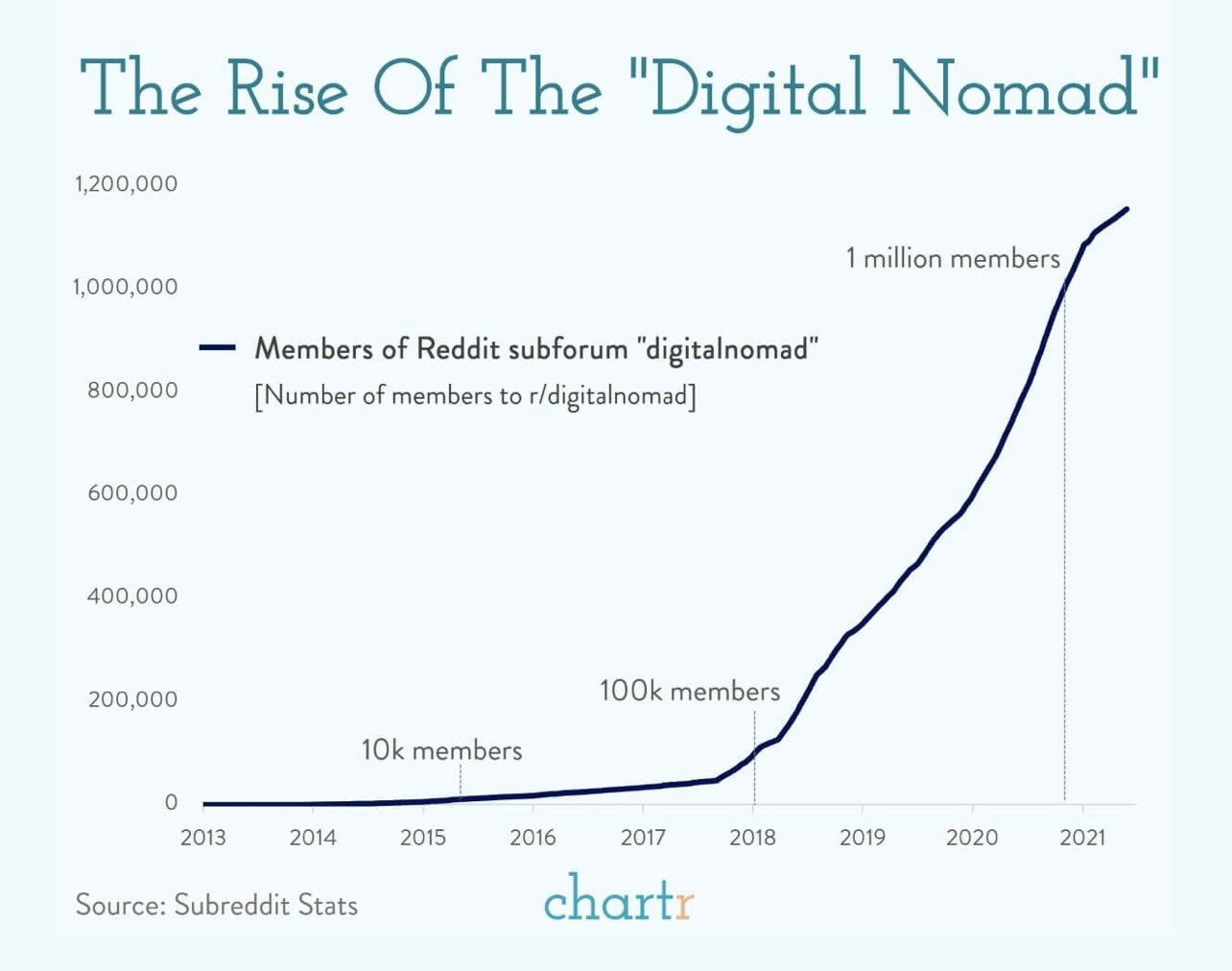

But for many people, that’s starting to change. Millions of people are “digital nomads”, working remotely and traveling the world.

In a world with borderless work—and in a world with borderless friendships born on the internet—does living in just one place make sense?

For many, it still does, but location is becoming more fluid. Airbnb is becoming as much about months-long non-vacation stays as it is about holiday getaways.

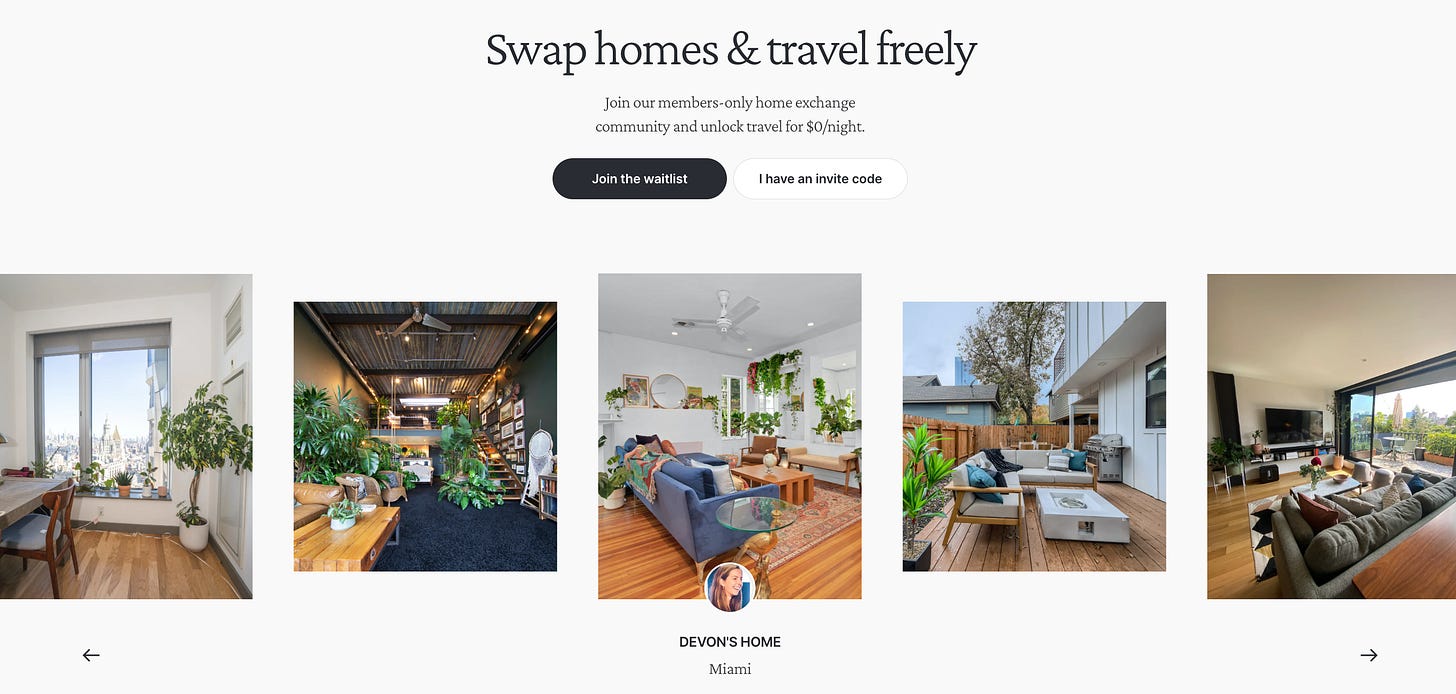

New startups are pioneering new concepts. Kindred lets you swap homes, sort of like Kate Winslet and Cameron Diaz in The Holiday.

Kindred’s vision is to expand the “sharing economy” to everyone, and to make stays away from home more affordable. There’s an interesting ripple effect in the marketplace: if I want to go spend a month in Austin, all of a sudden that opens up a home in New York City (my apartment); if someone wants to come to my place in NYC from LA, all of a sudden their place in LA is available. And so on.

You pay with an annual membership fee, vs. Airbnb’s egregious fees. (Side note: I think Airbnb’s deceptive and sky-high cleaning and service fees pose a serious brand risk to the business—one that the company isn’t taking seriously enough. When you become a meme, it’s rarely a good thing.)

Pacaso makes buying a second home more accessible by letting you buy with a group. A group of friends and I can each pitch in for 1/8th of a ski house in Aspen that Pacaso manages for us.

Summer also helps you buy a second home and rents it for you while you’re away. The goal is to abstract away complexity and make homeownership more affordable.

More and more people will spend some (or all) of the year in a place away from their “main” home—if they even have one. They might stay at an Airbnb or Kindred or Hipcamp, or they might invest in a new home with Pacaso or Summer.

In a technology-driven world, geography no longer rules our lives to the same degree.

Norm: Pursuing your passion

When I think of Gen Z’s approach to work, I think of a line from Ali Wong’s Netflix comedy special Baby Cobra:

Take that, Sheryl Sandberg.

There’s a growing backlash to the Millennial idea that your work should be your purpose in life. Work is shifting lower on Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: work doesn’t need to provide self-actualization; it just needs to provide basic needs like food and shelter. TikTok is full of adolescents proudly slamming their laptops shut at 5pm, despite being in the middle of a Zoom meeting.

One of the best pieces I’ve read in recent months is Anna Codrea-Rado’s long Vice piece called Inside the Online Movement to End Work. The journalist goes deep into r/antiwork, which has become one of Reddit’s most popular subreddits. The antiwork subreddit describes itself as “a subreddit for those who want to end work, are curious about ending work, and want to get the most out of a work-free life.” r/antiwork now has 2.1 million members (who fittingly call themselves “Idlers”), up from just 13,000 in 2019. Comically, the subreddit has three times as many members as r/careerguidance.

Our modern concept of work is actually relatively new—only about 300 years old. For most of human history—from the Greeks, to the Romans, to the Middle Ages—leisure was the basis of culture. Only in the 16th century, when the Reformation brought the rise of the Protestant work ethic, did people begin to see work as a way to bring oneself closer to God. The religious aspect of work faded, but faith in hard work persisted, evolving into the modern-day spirit of capitalism.

There was an excellent piece in The NYTimes last week from Tim Kreider. He captured the exhausted nihilism of a younger generation of workers. Some of my favorite excerpts:

I don’t believe most people are lazy. They would love to be fully, deeply engaged in something worthwhile, something that actually mattered, instead of forfeiting their limited hours on Earth to make a little more money for men they’d rather throw fruit at as they pass by in tumbrels.

I think people are enervated not just by the Sisyphean pointlessness of their individual labors but also by the fact that they’re working in and for a society in which, increasingly, they have zero faith or investment. The future their elders are preparing to bequeath to them is one that reflects the fondest hopes of the same ignorant bigots a lot of them fled their hometowns to escape.

More young people are opting not to have kids not only because they can’t afford them but also because they assume they’ll have only a scorched or sodden wasteland to grow up in. An increasingly popular retirement plan is figuring civilization will collapse before you have to worry about it. I’m not sure anyone’s composed a more eloquent epitaph for the planet than the stand-up comedian Kath Barbadoro, who tweeted: “It’s pretty funny that the world is ending and we all just have to keep going to our little jobs lol.”

I still hope to make it to my grave without ever getting a job job — showing up for eight or more hours a day to a place with fluorescent lighting where I’m expected to feign bushido devotion to a company that could fire me tomorrow and someone’s allowed to yell at you but you’re not allowed to yell back.

Our norm of work-centric life might be short-lived. If the image of 20th-century capitalism was commuting five days a week into Manhattan from Connecticut for your desk job in a midtown skyscraper, the image of 21st-century capitalism might be something quite different: working remotely and freelance for various companies, from various exotic beaches, as you travel the world and enjoy life 🏝. It won’t be that extreme for everyone, of course, but the tide does seem to be turning away from a work-obsessed culture.

Norm: Having one job

Part of that reality will likely be stitching together various income streams. The era of the single job might be over. For most of history, workers have held one profession throughout their careers. People’s names even came from their crafts: Smith for blacksmiths, Taylor for tailors, Webb for weavers, Ward for watchmen. (I can’t seem to recall where Baker, Cook, and Carpenter come from...)

But now, the world is going freelance. In 2027, America will become a freelance-majority workforce. A future “career” might look something like teaching an online course with Reforge, developing Overwolf in-game apps, sprinkling in some brand sponsorships on Instagram, and working a few days a week as a relief veterinary technician through Roo.

You can hire freelancers on companies like Fiverr, Toptal, and Upwork. And a new infrastructure is being built for this world of work. Found, for instance, lets self-employed people manage their banking, bookkeeping, taxes, and invoices.

Having more than one job will be the new normal.

Final Thoughts

I could keep going. The world is changing at an alarming speed, and foundational parts of our everyday lives will soon become extinct. Our kids will ask us why we call charging stations / convenience stores “gas stations”, and we’ll explain to them that cars used to run on gasoline. (*gasp*)

This week’s piece covered many work-related norms: the office, our 5-day workweek, where we live, the careers we pursue. Next week, I’ll do a part 2 that covers norms outside of work, touching on trends like secondhand clothing, plant-based meat alternatives, and the death (or rebirth?) of movie theaters.

I’d also love to include norms ripe for change that I haven’t thought of. Shoot me an email if you’ve thought of one. I’ll share the most interesting submissions next week.

See you next week for part ✌️

Sources & Additional Reading

This Is Water | David Foster Wallace (I promise, this is the best thing you’ll read this week)

It’s Time to Stop Living the American Scam | Tim Kreider, NYTimes

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: