Throughlines (Part I)

Taking the 10,000-Foot View

This is a weekly newsletter about how people and technology intersect. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Throughlines (Part I)

In 2016, I decided to run a half marathon in a suit and tie.

There wasn’t much forethought put into it. I’d already signed up to run the New York Half Marathon when I read an article about a guy in Massachusetts setting the Guinness World Record for “Fastest Half Marathon in a Business Suit”. I thought it could be fun to try to beat his time of 1:24:41, so I went for it. Motivated by spectators yelling “How’s the commute?!”—and in spite of some major chafing—I managed a 1:18:42 to nab the record.

Well, technically, before my record could be officially ratified by Guinness, someone read about my record in Runner’s World and went out and broke it 😔 I opted to not try to get it back—it’s a fun story once, but you don’t want to become the guy perennially running races in a suit.

I tell this story for two reasons:

First, because it demonstrates the power of the internet and how interconnected we all are, which is relevant to today’s piece. I read about someone setting the record so I went out and broke it. Then a guy 3,500 miles away in the UK read about it, so he broke it. (Then someone in Australia quickly went and broke his record.) The world is smaller than ever.

Second, because it gives me an excuse to mention that I’m running the New York Marathon next week—no, not in a suit and tie—and that I’m running for Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Every dollar will go toward ovarian cancer research. I would really appreciate any and all donations—if you’re interested in contributing $5 or $10, my fundraising page is here.

Anyway, where were we? Oh yeah—our digital interconnectivity. Back in May, I wrote Chain Reactions: How Creators, Web3, and the Metaverse Intersect in an attempt to zoom out and offer a 10,000-foot view of how the topics I write about in Digital Native connect. I even offered an oversimplified, one-paragraph summary:

We’re becoming a digital-first species, and at the same time we’re rejecting institutions. Those two factors are combining to make work more disaggregated and creative, fueling the creator economy and letting everyone build with technology. Web3 and new business models will better allow creators and their communities to capture and exchange value, forming robust digital economies. Ultimately, this will lead to an immersive, decentralized metaverse.

That’s a lot of buzzwords packed into one paragraph—creator economy, Web3, decentralized, metaverse. Six months have gone by since I wrote that, and I thought it was again worth stepping back. This time, fittingly, I’ll do so through the lens of buzzwords—the words and terms you hear again and again in 2021. I’ll dive into 10 of them and take a stab at connecting the dots.

Community

Authenticity

Avatars

Metaverse

VR & AR

Web3

Creators

DeFi

Tokens (Fungible & Non-Fungible)

DAOs

This week, I’ll cover #1-5; next week, I’ll cover #6-10. Let’s jump in.

🙏 Community

I started Chain Reactions with a Taylor Swift lyric:

'Cause we were like the mall before the internet

It was the one place to be

This line from the song “Coney Island” captures the longing for a bygone relationship. But it also, in some ways, captures how we’ve become a predominantly digital species.

The internet is the new mall: 4.5 billion people are online—60% of the human race. The internet is where we seek and find community.

What’s fascinating is that today’s communities are both the deepest and the broadest in human history. During last week’s Index Creator Summit, Discord’s Jason Citron mentioned that Discord has 19 million (!) active servers. Each is the living, breathing nucleus of a community. Jack Conte of Patreon framed it this way: you may think your interests are niche—maybe only 1 in 1,000 people like the same things as you—but with 4 billion people online, that’s 4 million people who share your interests. On the internet, nothing is too niche.

At the same time, the internet’s scale unlocks breadth: 142 million Netflix accounts watched Squid Game in its first month—67% of all accounts around the world. The pace of internet culture means cultural phenomena have shorter durations (there will be another hit show next month), but this scale has never been seen before.

Over the weekend, I came across this comment on TikTok:

kweenboi666 (quite the handle) is right. The sounds and challenges on TikTok are enormous, collective jokes shared by millions of creators and a billion monthly active users. One week, it’s a cranberry juice-drinking, Fleetwood Mac-listening skateboarder; the next, we’re all debating “it’s giving cher” 💅; last month, we were all on couch guy TikTok. Lying in bed scrolling our FYP, we feel like we belong.

There are interesting companies building for online belonging: Geneva is a hub for all your community chats; Yoni Circle provides community for women through storytelling; Circle equips creators with the tools to manage their community.

Last week, Ian Bogost argued in The Atlantic that the internet actually lets us talk too much—that humans were never meant to talk and be heard to this extent. He writes:

A lot is wrong with the internet, but much of it boils down to this one problem: We are all constantly talking to one another. Take that in every sense. Before online tools, we talked less frequently, and with fewer people. The average person had a handful of conversations a day, and the biggest group she spoke in front of was maybe a wedding reception or a company meeting, a few hundred people at most.

He might be right, but the floodgates of online communication are open. Everyone now has a megaphone. Bogost argues that Facebook should be more like how Google+ was originally conceived, back in 2011: built for intimate, small-group relationships.

But what if Discord is the better version of Google+? Those 19 million Discord communities aren’t built for a 2011 social graph like Google+ was—your work friends, your hockey league—but for a 2021 social graph: your multinational Fortnite team, your fellow Nicki Minaj stans, and so on.

📹 Authenticity

Last month, Zoolander celebrated its 20th anniversary. Back in 2001, Ben Stiller’s brainchild (Stiller also directed the film) was a massive flop—critics panned it as a “one-joke movie” and it was a box office failure. But it’s since become a cult phenomenon, perhaps most famous for Derek Zoolander’s “Blue Steel” pose:

In some ways, Zoolander foreshadowed our self-obsessed social media culture. John Hamburg, the film’s writer, says, “It kind of predated social media, obviously, but I think it tapped into these things that were brewing and would explode with the Kardashians.”

Ilana Kaplan at Esquire put it best:

The film held a magnifying glass to a culture that was consumed by narcissism and an obsession with appearances…And as for “Blue Steel,” “Le Tigre” and “Magnum”? They’re all different versions of “duck face.” In 2021, whether we’d like to admit it or not, we’re all just Derek and Hansel—but with better lighting.

“Authenticity” has become an overused word—especially when tied to Gen Z—but it also captures a collective exhaustion with the narcissistic, image-obsessed internet culture of the past decade. This year’s social media upstarts have leaned into authenticity. I wrote about three of them in June’s The Evolution of Social Media: BeReal, Dispo, and Poparazzi. In many ways, they’re taking on Instagram, which began as a literal filtered version of reality. (A side note: while Instagram’s filters were meant to beautify your images, many filters on Snapchat and TikTok purposefully make you look uglier. It’s a fascinating distinction in how the products were designed and, consequently, in the types of users they attract.)

Authenticity shows up in the types of platforms we’re spending time on. Facebook and Instagram use are down; iMessage and TikTok use are up. Mark Zuckerberg actually emphasized this in Facebook’s earnings release this week:

Facebook Chief Executive Mark Zuckerberg, on an analysts call, also addressed Facebook’s growing competition for young adult users from Apple’s iMessage app and the rise of ByteDance’s TikTok, saying that retaining and adding members of this demographic segment is essential for the company’s long-term success.

What’s interesting is that iMessage and TikTok are polar opposites: iMessage is where you connect with your closest contacts, and TikTok is where you connect with strangers. Facebook’s suite of products falls into the wasteland of “loose social ties” in the middle. Zuckerberg is being attacked from both sides.

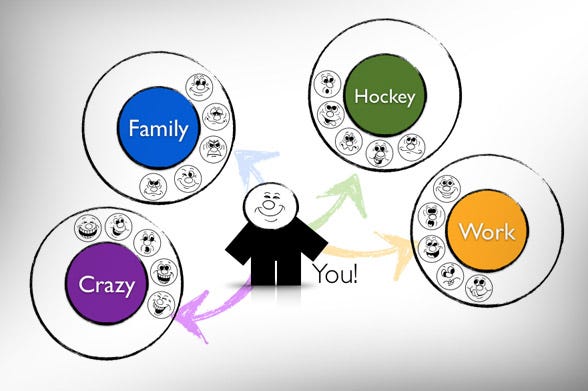

I often use a framework of concentric circles:

Ring 1 and Ring 4 are the future.

And as we shift to more Ring 1 and Ring 4 platforms, we emphasize authenticity over aspiration.

👽 Avatars

Authenticity brings us to avatars. This might seem a strange connection: aren’t avatars, by nature, inauthentic? After all, avatars entail being someone other than yourself. But for many people, avatars are a vessel for more authentic self-expression.

This shows up in the root of the word: the word “avatar” originates from Hinduism, where it stands for the “descent” of a deity into terrestrial form. In 1985, the video game developer Richard Garriott used the word to refer to his player in a video game—Garriott wanted his player’s character to be his Earth self manifested into the virtual world—and the word caught on. Avatars have evolved into digital representations of who we are or who we hope to be.

The vTuber (virtual YouTuber) Ironmouse is a creator who streams in the form of a pink-haired anime girl. Here she is being interviewed by Anthony Padilla:

Ironmouse became a vTuber because of an autoimmune disorder—Common Variable Immune Deficiency, or CVID—that limited her offline life. She remembers: “I got so sick that I couldn’t go out. My contact with people was very limited and I felt that I couldn’t really be a human. So I started being a vTuber.” Ironmouse found community online and, crucially, was able to express herself in a body she felt comfortable in: she says, “I have never felt more myself than I have in this digital body.”

Equally fascinating is Sam Kelly, a man who spends hours in a virtual world called Stardew Valley. Sam writes:

“In the real world, I am a burly 27-year-old man with a bushy beard. In the video game, I am Olivianne, a strapping blue-haired woman married to Penny.”

Sam’s avatar allows him to be a lesbian with two children who raises livestock. This unlocks a new side of him: a self-proclaimed introvert in the real-world, Sam is “a social butterfly” in Stardew Valley.

New companies are bringing avatars to life in new ways. RTFKT, for instance, is a digital fashion house that sells NFT sneakers. You can envision one day wearing these sneakers in a virtual world.

Genies allows anyone to design their own avatar and then buy digital clothing and accessories. Here’s my Genie—in the photo on the right, I’m doing my best Blue Steel impression.

And Ready Player Me is a cross-game avatar platform. Game developers can quickly integrate avatars into their game, while players can snap a selfie (which generates their avatar) and then use that avatar in 660 supported games.

Ready Player Me calls itself “Your passport to the metaverse.”

🪐 Metaverse

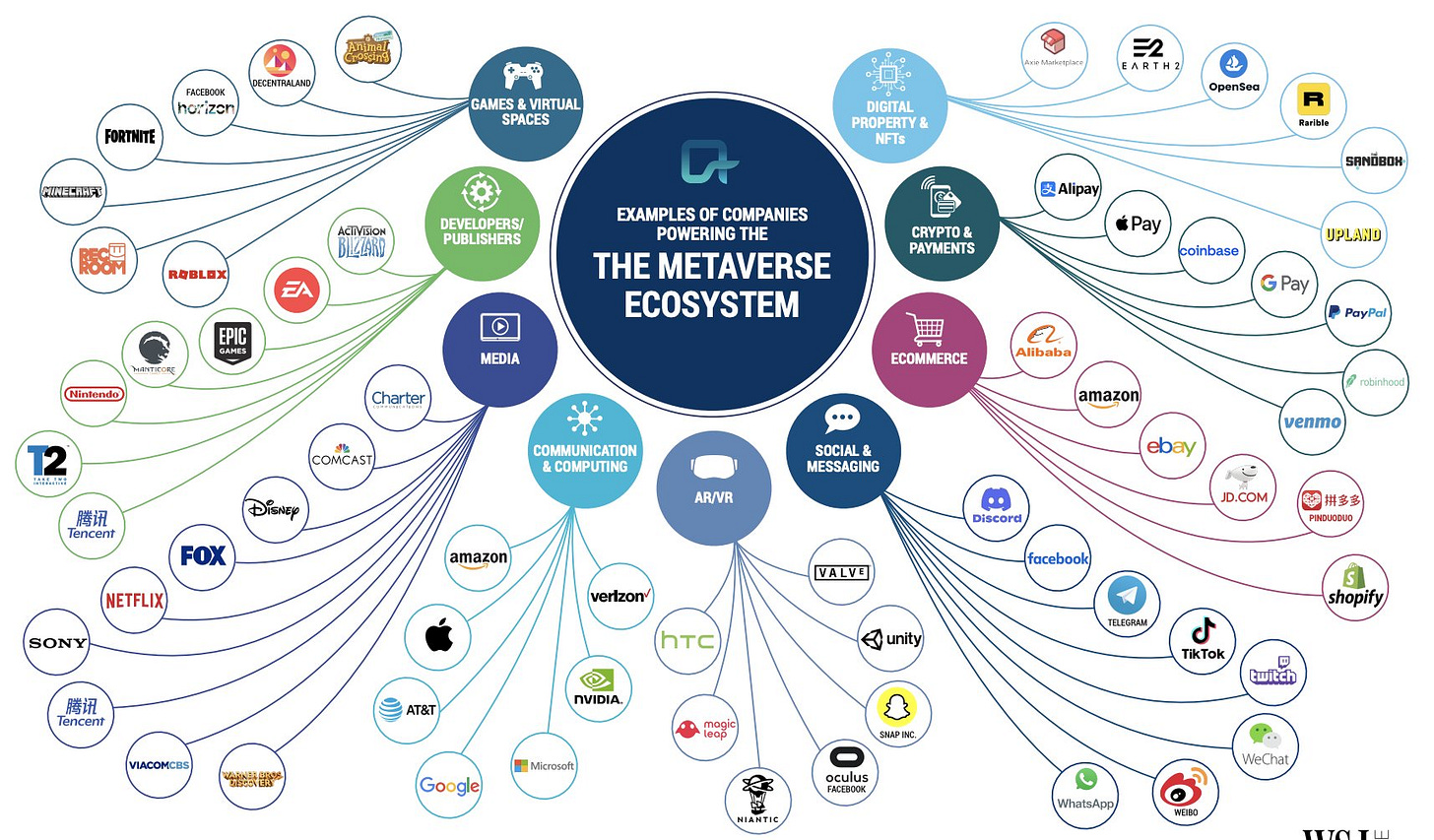

The metaverse is perhaps the buzzword of 2021, but there’s been a long road leading up to this point:

And as this graphic helpfully captures, “the metaverse” has many components: gaming, media, messaging, commerce, crypto.

In perhaps the biggest sign yet that the metaverse is now mainstream, Vanity Fair published a piece last week called The Metaverse Is About to Change Everything. My favorite part of the piece is when Nick Bilton envisions what this future could look like:

The number of possibilities around the metaverse are endless, but you can easily imagine how it might change the way we interact in the same way that mobile devices have changed society today. In a world where the metaverse exists, rather than hosting a weekly meeting on Zoom with all of your coworkers, you could imagine meeting in a physical representation of your office, where each person looks like a digital version of themselves, seated at a digital coffee table drinking digital artisanal coffee and snacking on digital donuts. If that sounds a bit boring, you could meet somewhere else, perhaps in the past, like in 1776 New York City, or in the future, on a spaceship, or at the zoo, on another planet—if it made sense for the meeting, of course. You could choose not to be yourself, but rather some form of digital avatar you picked up at the local online NFT swap meet, or at a virtual Balenciaga store. You could dress like a bunny rabbit to go to the meeting. A dragon. A dead dragon. And that’s just one measly little meeting. Imagine what the rest of the metaverse might look like.

You could play first-person shooter video games in the metaverse, that look like they’re in real life. You could take a British history class taught by a digital representation of King George III, or learn about the theory of relativity from Albert Einstein himself. You could attend a TED Talk, or give one, or go to church. You could hook up your exercise bike to race against Maurice Garin in the Tour de France. Or your running machine to race against Usain Bolt at the Olympics (and lose). You could go to the zoo. You could be an animal at the zoo. Visit the Louvre. Le Mans. The International Space Station. You could go for a walk on Mars. Neptune. Float in space. Play “red light, green light” with your friends in Squid Game. You could go shopping, trying on outfits that once you pay for, are actually mailed to your house. You could go to a theme park and ride the world’s biggest roller coaster and maybe even throw up in real life. There are also lots of potential dark sides of the metaverse. Don’t be surprised to see Nazi rallies and people who choose racist and dangerous avatars, or hackers stealing from people, or performing metaversal terrorism, whatever that becomes. All of this stuff could be for sale in crypto, where we buy and sell digital goods with Bitcoin or Ethereum.

That’s a long excerpt, but it beautifully captures how grand this future could be. Some elements are already coming to fruition. That virtual Balenciaga store? It already exists in Fortnite:

The rest of the possibilities Bilton floats will soon exist in VR and AR.

🔮 VR and AR

Virtual reality and augmented reality are the ultimate vessels for the metaverse. Our phones and computers and gaming consoles can act as portals, but VR and AR will deliver the metaverse in its truest form—vibrant, three-dimensional, immersive.

We’re still in the early days of VR and AR, but things are picking up. VR software sales inflected in 2019. By early 2020, over 100 VR titles had broken $1M in revenue. VR is finally moving from product to platform.

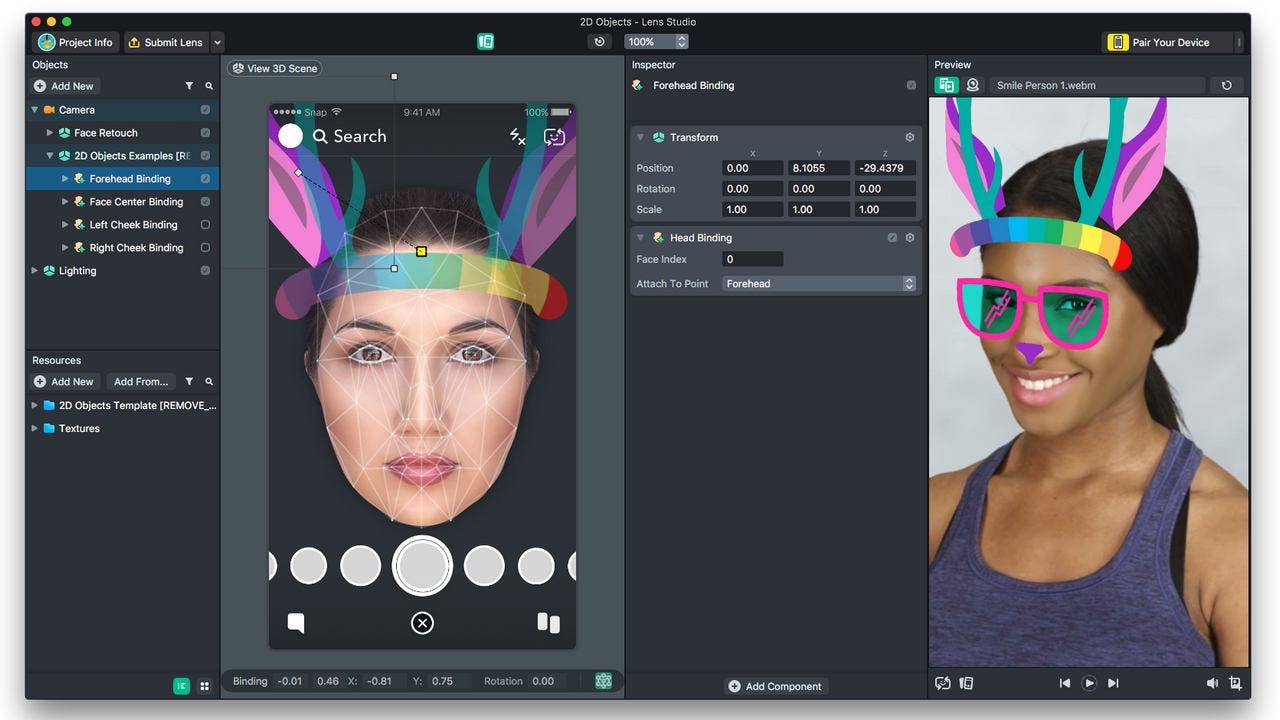

And on the AR side, Snap has been quietly building a robust platform of its own. Lens Studio lets developers build their own AR experiences with a set of accessible tools.

200 million Snapchat users interact with AR in the app every day, and “AR creator” is rapidly becoming a new job title.

Bilton envisioned part of our AR future in his Vanity Fair piece:

Maybe you come across as a three-headed puppy with multicolored pigtails to your kids, but a professional in a suit to your coworkers. In this scenario, you could play a game of Pac-Man in the real world, running around trying to capture virtual coins that no one else can see, or evading multicolored ghosts who want to eat you alive. You could sit in a coffee shop in New York while a friend sits in a coffee shop in Paris, and both have a “real” coffee together, even though you’re not in the same place.

Snap has been innovating on AR for years—its famous puppy-dog filter came out five years ago—but Snap is still criminally underrated for its efforts. Lens Studio and the creativity it unlocks will push forward AR, making it more accessible to both creators and end users. That’s one step closer to the realization of the metaverse.

Final Thoughts

It’s impossible to touch on these topics—metaverse, avatars, community—without talking about crypto. Next week, I’ll focus on five crypto-related buzzwords: creators, Web3, tokens (both NFTs and fungible tokens), DAOs, and DeFi. We’re becoming a digital species, and crypto underpins our new digital economy.

Stay tuned for Part II next week!

Sources & Additional Reading

Activate Technology and Media Outlook for 2022 | Activate & WSJ

Zoolander’s 20th Anniversary | Ilana Kaplan

How the Metaverse Is About to Change Everything | Nick Bilton

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: