This is a weekly newsletter about how people and technology intersect. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Throughlines

There are a lot of words we hear again and again in 2021—metaverse, NFT, creator, Web3. Given the sheer pace of innovation, it’s become hard to keep up and easy to lose the forest for the trees. But the thing is, these words all connect: they interrelate and build on one another to forge a new digital future.

Six months ago, I wrote Chain Reactions to make sense of it all. I thought it was again time to step back and offer the 10,000-foot view of how the topics I write about in Digital Native intersect. And what better way to do so than through the lens of those buzzwords? In this piece, I’ll dive into 10 buzzwords:

Community

Authenticity

Avatars

Metaverse

VR & AR

Web3

Tokens (Fungible & Non-Fungible)

DeFi

DAOs

Creators

I’ll unpack each one and take a stab at connecting the dots. Let’s jump in.

🙏 Community

On her song “Coney Island”, Taylor Swift sings:

'Cause we were like the mall before the internet

It was the one place to be

It’s a simple line that captures the longing for a bygone relationship. But it also, in my mind, captures how we’ve become a predominantly digital species. The internet is the new mall: 4.5 billion people are online—60% of the human race. The internet is where we seek and find community.

What’s fascinating is that today’s communities are both the deepest and the broadest in human history. During last month’s Index Creator Summit, Discord’s Jason Citron mentioned that Discord has 19 million (!) weekly active servers. That’s up +184% from 6.7 million a year ago. Each server is the living, breathing nucleus of a community. Jack Conte of Patreon framed it this way: you may think your interests are niche—maybe only 1 in 1,000 people like the same things as you—but with 4 billion people online, that’s 4 million people who share your interests. On the internet, no niche is too niche.

At the same time, the internet’s scale unlocks breadth: 142 million Netflix accounts watched Squid Game in its first month—67% of all accounts around the world. The pace of internet culture means cultural phenomena have shorter durations (there will be another hit show next month), but this scale has never been seen before.

Over the weekend, I came across this comment on TikTok:

kweenboi666, whoever you are: you’re right. The sounds and challenges on TikTok are massive, collective jokes shared by millions of creators and a billion monthly active users. One week, it’s a cranberry juice-drinking, Fleetwood Mac-listening skateboarder; the next, we’re all debating “it’s giving cher” 💅; last month, we were all on couch guy TikTok. Lying in bed scrolling our FYP, we feel like we belong.

There are interesting companies building for online belonging: Geneva is a hub for all your community chats; Yoni Circle provides community for women through storytelling; Circle equips creators with the tools to manage their community.

Last week, Ian Bogost argued in The Atlantic that the internet actually lets us talk too much—that humans were never meant to talk and be heard to this extent. He writes:

A lot is wrong with the internet, but much of it boils down to this one problem: We are all constantly talking to one another. Take that in every sense. Before online tools, we talked less frequently, and with fewer people. The average person had a handful of conversations a day, and the biggest group she spoke in front of was maybe a wedding reception or a company meeting, a few hundred people at most.

He might be right, but the floodgates of online communication are open. Everyone now has a megaphone. Bogost argues that Facebook should be more like how Google+ was originally conceived, back in 2011: built for intimate, small-group relationships.

But what if Discord is the better version of Google+? Those 19 million Discord communities aren’t built for a 2011 social graph like Google+ was—your work friends, your hockey league—but for a 2021 social graph: your multinational Fortnite team, your fellow Nicki Minaj stans, and so on. Belonging is borderless.

In Digital Kinship last spring, I wrote about our loneliness epidemic—about how nearly half of Americans always or sometimes feel alone (46%) or left out (47%). The internet is both a cause of and an antidote to our loneliness epidemic. Soul, China’s 5th-most-popular social app, emphasized this duality in its S1 filing:

We have especially attracted young generations in China, who are native to mobile internet and who therefore more palpably experience the loneliness technologies bring.

As more of our lives go digital, we more deeply feel the gaps where rich, in-person interactions used to be. Yet technology is also a salve for that isolation, connecting us in new ways to new people. Soul’s filing mentions the word “community” 43 times.

Another Chinese internet company, Bilibili, has grown to a $33 billion market cap by nurturing niche communities. Bilibili has 202 million monthly active users (putting it not far behind Snapchat) who are averaging 75 minutes of daily engagement (for reference, Instagram and TikTok are 53 minutes and 52 minutes, respectively).

What’s most unique about Bilibili is how engaged and retentive its communities are. Bilibili achieves this by building friction into community. In order to join a Bilibili community, users must pass a 100-question test. A sample question from the quiz to join the Game of Thrones community, according to Lillian Lin: “Which of the following is not part of the Faith of Seven?” (For what it’s worth, I watched all eight seasons and there’s zero chance I could answer that question.) Bilibili used to require an 80% correct score to enter the community, though it’s become more lenient over time. Building in friction means that communities are comprised only of superfans; 80%+ of users retain after 12 months.

The search for online belonging manifests in many ways: the casual livestreaming category “Just Chatting” becoming Twitch’s fastest-growing category; the rise of creator fandoms; even the phenomenon of sleep streaming—watching other people sleep over livestream.

If the 2010s were the decade of performance online—status and signaling in broad brushstrokes, through likes and retweets and follower counts—the 2020s are the decade of deep and engaged digital communities.

📹 Authenticity

Last month, Zoolander celebrated its 20th anniversary. Back in 2001, Ben Stiller’s brainchild (Stiller also directed the film) was a massive flop—critics panned it as a “one-joke movie” and it was a box office failure. But it’s since become a cult phenomenon, perhaps most famous for Derek Zoolander’s “Blue Steel” pose:

In some ways, Zoolander foreshadowed our self-obsessed social media culture. John Hamburg, the film’s writer, says, “It kind of predated social media, obviously, but I think it tapped into these things that were brewing and would explode with the Kardashians.”

Ilana Kaplan at Esquire put it best:

The film held a magnifying glass to a culture that was consumed by narcissism and an obsession with appearances…And as for “Blue Steel,” “Le Tigre” and “Magnum”? They’re all different versions of “duck face.” In 2021, whether we’d like to admit it or not, we’re all just Derek and Hansel—but with better lighting.

“Authenticity” has become an overused word—especially when tied to Gen Z—but it also captures a collective exhaustion with the narcissistic, image-obsessed internet culture of the past decade. This year’s social media upstarts have leaned into authenticity. I wrote about three of them in June’s The Evolution of Social Media: BeReal, Dispo, and Poparazzi. In many ways, they’re taking on Instagram, which began as a literal filtered version of reality. (A side note: while Instagram’s filters were meant to beautify your images, many filters on Snapchat and TikTok purposefully make you look less attractive. It’s a fascinating distinction in how the products were designed and, consequently, in the types of users they attract.)

Authenticity shows up in the types of platforms we’re spending time on. More “authentic” platforms like Snapchat and TikTok continue to thrive.

More 13- to 34-year-olds in the U.S. are on Snapchat than are on Instagram or TikTok. Evan Spiegel’s strategy is to 1) keep younger users as they age, and 2) attract new cohorts of young users. It seems to be working.

Facebook and Instagram use are down; iMessage and TikTok use are up. Mark Zuckerberg emphasized this in Facebook’s earnings release last month:

Facebook Chief Executive Mark Zuckerberg, on an analysts call, also addressed Facebook’s growing competition for young adult users from Apple’s iMessage app and the rise of ByteDance’s TikTok, saying that retaining and adding members of this demographic segment is essential for the company’s long-term success.

What’s interesting is that iMessage and TikTok are polar opposites: iMessage is where you connect with your closest contacts, and TikTok is where you connect with strangers. Facebook’s suite of products falls into the wasteland of “loose social ties” in the middle. Zuckerberg is being attacked from both sides.

I often use a framework of concentric circles for the future of social:

Ring 1 and Ring 4 are the future.

And as we shift to more Ring 1 and Ring 4 platforms, we emphasize authenticity over aspiration.

👽 Avatars

Authenticity brings us to avatars. This might seem a strange connection: aren’t avatars, by nature, inauthentic? After all, avatars entail being someone other than yourself. But for many people, avatars are a vessel for more authentic self-expression.

This shows up in the root of the word: the word “avatar” originates from Hinduism, where it stands for the “descent” of a deity into terrestrial form. In 1985, the video game developer Richard Garriott used the word to refer to his player in a video game—Garriott wanted his player’s character to be his Earth self manifested into the virtual world—and the word caught on. Avatars have evolved into digital representations of who we are or who we hope to be.

The vTuber (virtual YouTuber) Ironmouse is a creator who streams in the form of a pink-haired anime girl. Here she is being interviewed by Anthony Padilla:

Ironmouse became a vTuber because of an autoimmune disorder—Common Variable Immune Deficiency, or CVID—that limited her offline life. She remembers: “I got so sick that I couldn’t go out. My contact with people was very limited and I felt that I couldn’t really be a human. So I started being a vTuber.” Ironmouse found community online and, crucially, was able to express herself in a body she felt comfortable in: she says, “I have never felt more myself than I have in this digital body.”

Equally fascinating is Sam Kelly, a man who spends hours in a virtual world called Stardew Valley. Sam writes:

“In the real world, I am a burly 27-year-old man with a bushy beard. In the video game, I am Olivianne, a strapping blue-haired woman married to Penny.”

Sam’s avatar allows him to be a lesbian with two children who raises livestock. This unlocks a new side of him: a self-proclaimed introvert in the real-world, Sam is “a social butterfly” in Stardew Valley.

We’re seeing more creators lean in to digital self-expression. I’ve written extensively about Miko, who I also had the chance to interview during the Index Creator Summit. “The Technician” leverages the Unreal Engine and her mo-cap suit to embody Miko.

When I think of avatars, I often think of a quote from Ready Player One. Asked why people visit the OASIS—a vast, immersive virtual world—the protagonist says: “People come to the OASIS for all the things they can do, but they stay because of all the things they can be.” People stay for who they can be.

Within worlds like Minecraft and Roblox and Fortnite, people are already embodying new digital identities. In Fortnite, you can pay ~1,500 V-Bucks (~$15) to be Iron Man or a Patriots player or Marshmello.

Outfitting our avatars in virtual worlds has become a massive business: a decade ago, microtransactions made up 20% of gaming revenue; today, they make up 75%. By 2025, they’re expected to grow to 95%.

But our digital items exist within walled gardens: your Fortnite skin doesn’t work in Roblox. New companies are bringing avatars to life in new ways, often by building interoperability into digital assets. RTFKT, for instance, is a digital fashion house that sells NFT sneakers. You can envision one day wearing these sneakers between virtual worlds.

Genies allows anyone to design their own avatar and then buy digital clothing and accessories. Here’s my Genie—in the photo on the right, I’m doing my best Zoolander Blue Steel impression.

And Ready Player Me is a cross-game avatar platform. Game developers can quickly integrate avatars into their game, while players can snap a selfie (which generates their avatar) and then use that avatar in 660 supported games.

Fittingly, Ready Player Me calls itself “Your passport to the metaverse.”

🪐 Metaverse

The metaverse is perhaps the buzzword of 2021, but there’s been a long road leading up to this point:

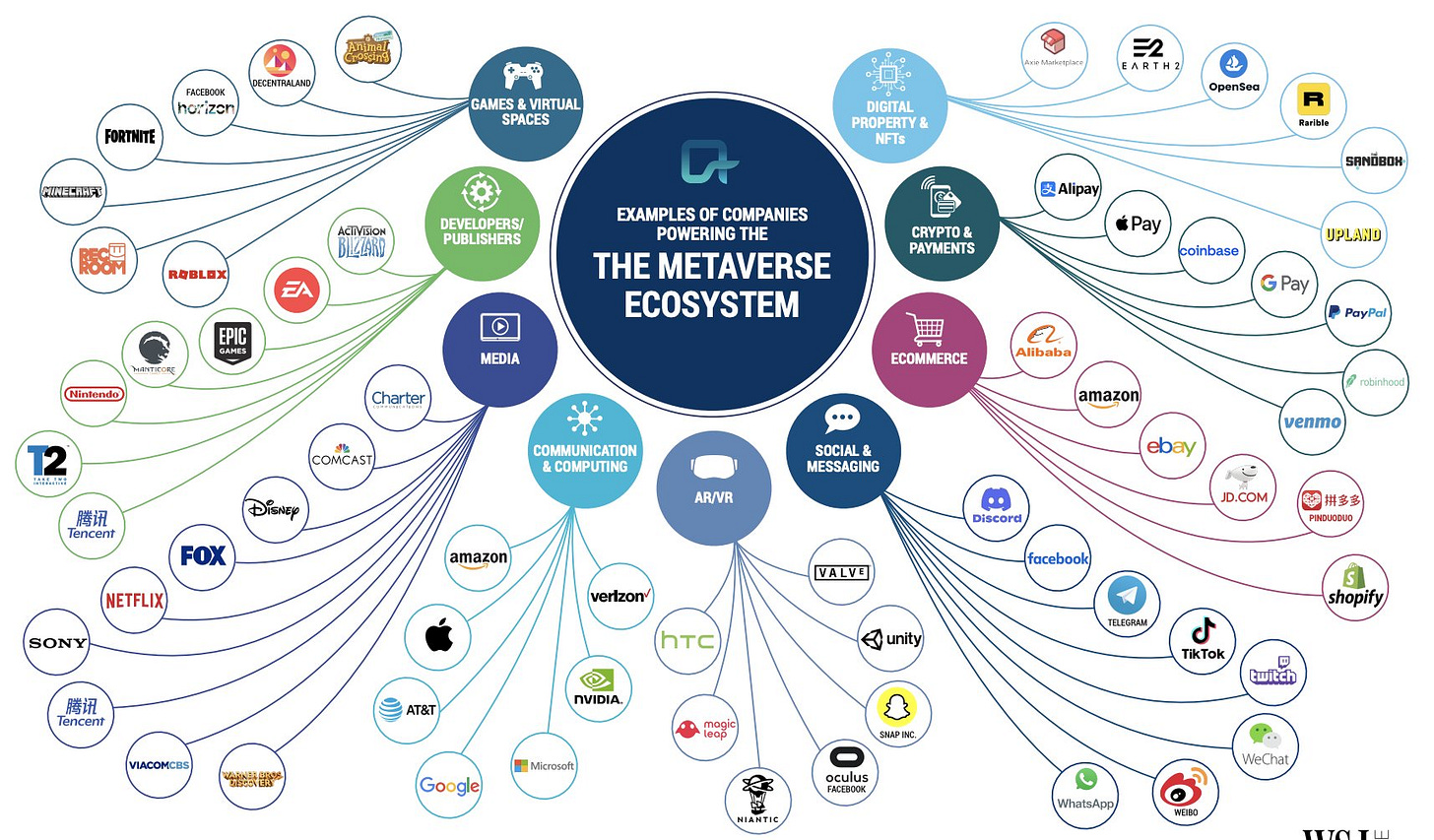

We’ve been building toward this future for years; as I wrote about in July, even Neopets helped paved the way. And as the below graphic helpfully captures, “the metaverse” has many components: gaming, media, messaging, commerce, crypto. Of course, these aren’t metaverse companies themselves—but they’re building a digital future that will accelerate our road to the metaverse.

In perhaps the biggest sign yet that the metaverse is now mainstream, Vanity Fair published a piece last month called The Metaverse Is About to Change Everything. My favorite part of the piece is when Nick Bilton envisions what this future could look like:

The number of possibilities around the metaverse are endless, but you can easily imagine how it might change the way we interact in the same way that mobile devices have changed society today. In a world where the metaverse exists, rather than hosting a weekly meeting on Zoom with all of your coworkers, you could imagine meeting in a physical representation of your office, where each person looks like a digital version of themselves, seated at a digital coffee table drinking digital artisanal coffee and snacking on digital donuts. If that sounds a bit boring, you could meet somewhere else, perhaps in the past, like in 1776 New York City, or in the future, on a spaceship, or at the zoo, on another planet—if it made sense for the meeting, of course. You could choose not to be yourself, but rather some form of digital avatar you picked up at the local online NFT swap meet, or at a virtual Balenciaga store. You could dress like a bunny rabbit to go to the meeting. A dragon. A dead dragon. And that’s just one measly little meeting. Imagine what the rest of the metaverse might look like.

You could play first-person shooter video games in the metaverse, that look like they’re in real life. You could take a British history class taught by a digital representation of King George III, or learn about the theory of relativity from Albert Einstein himself. You could attend a TED Talk, or give one, or go to church. You could hook up your exercise bike to race against Maurice Garin in the Tour de France. Or your running machine to race against Usain Bolt at the Olympics (and lose). You could go to the zoo. You could be an animal at the zoo. Visit the Louvre. Le Mans. The International Space Station. You could go for a walk on Mars. Neptune. Float in space. Play “red light, green light” with your friends in Squid Game. You could go shopping, trying on outfits that once you pay for, are actually mailed to your house. You could go to a theme park and ride the world’s biggest roller coaster and maybe even throw up in real life. There are also lots of potential dark sides of the metaverse. Don’t be surprised to see Nazi rallies and people who choose racist and dangerous avatars, or hackers stealing from people, or performing metaversal terrorism, whatever that becomes. All of this stuff could be for sale in crypto, where we buy and sell digital goods with Bitcoin or Ethereum.

That’s a long excerpt, but it beautifully captures how grand this future could be. Some elements are already coming to fruition. That virtual Balenciaga store? It already exists in Fortnite:

And if Bilton’s vision sounds far-off, remember how rapidly technology has progressed over the past 20 years. Here’s the progression of Lara Croft’s avatar from 1998 through 2018:

Technology is becoming more and more powerful, better forging digital worlds and digital identities that rival their analog counterparts. Unreal Engine, for instance, launched MetaHuman Creator as a tool for creating believable digital humans within minutes. Each of these faces was made by MetaHuman:

Or consider one of the most simultaneously fascinating and unnerving websites out there, ThisPersonDoesNotExist.com. Each time you refresh the website, a new human face is digitally rendered. Here are four such faces—none of these people exist:

We’re hurtling towards our metaverse future. The full manifestation is still years (decades?) off, but the bricks are being laid. The next steps are VR and AR.

🔮 VR and AR

Virtual reality and augmented reality are the ultimate vessels for the metaverse. Our phones and computers and gaming consoles can act as portals, but VR and AR will deliver the metaverse in its truest form—vibrant, three-dimensional, immersive.

We’re still in the early days of VR and AR, but things are picking up. VR software sales inflected in 2019. By early 2020, over 100 VR titles had broken $1M in revenue. VR is finally moving from product to platform.

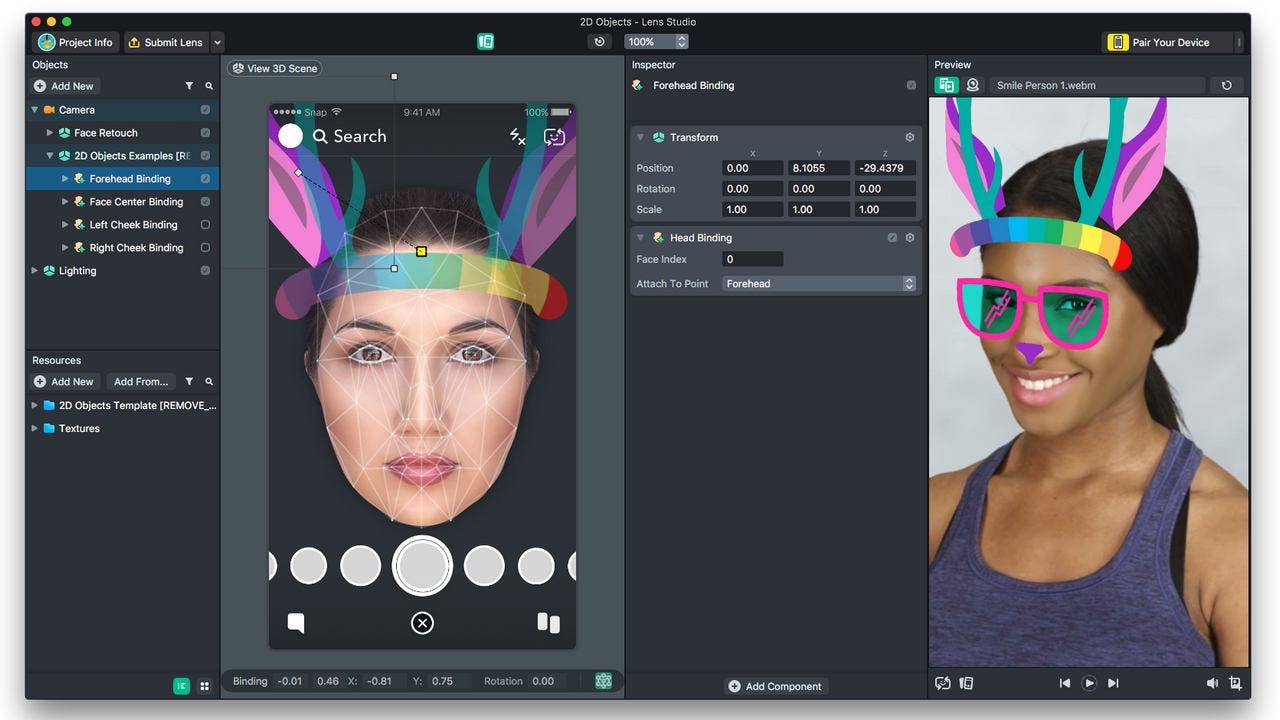

And on the AR side, Snap has been quietly building a robust platform of its own. Lens Studio lets developers build their own AR experiences with a set of accessible tools.

200 million Snapchat users interact with AR in the app every day, and “AR creator” is rapidly becoming a new job title.

Bilton envisioned our AR future in his Vanity Fair piece:

Maybe you come across as a three-headed puppy with multicolored pigtails to your kids, but a professional in a suit to your coworkers. In this scenario, you could play a game of Pac-Man in the real world, running around trying to capture virtual coins that no one else can see, or evading multicolored ghosts who want to eat you alive. You could sit in a coffee shop in New York while a friend sits in a coffee shop in Paris, and both have a “real” coffee together, even though you’re not in the same place.

Snap has been innovating on AR for years—its famous puppy-dog filter came out five years ago—but Snap is still criminally underrated for its efforts. Lens Studio and the creativity it unlocks will push forward AR, making it more accessible to both creators and end users. That’s one step closer to the realization of the metaverse.

How Crypto Fits In

On a run in New York last week, while in town for NFT NYC, David Bowie’s “Changes” came on my playlist. As I ran along the Hudson, a few lines jumped out:

And these children that you spit on

As they try to change their worlds

Are immune to your consultations

They’re quite aware of what they’re goin’ through

Bowie’s song—one of his best—is about defying the status quo and stepping out to, well, change the world. To me, the lines captured much of the crypto movement.

It’s easy to look down on crypto or to dismiss it, particularly given the market’s irrational exuberance. Skepticism often falls along generational lines: almost everyone I met at NFT NYC was young; almost everyone I know at OpenSea is between the ages of 25 and 30; and it’s not uncommon for crypto people to refer to all non-believers as “Boomers”. Change often comes from the young. Bowie’s lyrics apply as much to Greta Thunberg, as to X Gonzalez, as to Vitalik Buterin.

This isn’t to say that a JPEG of a Clipart rock will still be worth $1.3 million in a few years. Many (most?) of today’s headline-grabbing NFT sales will end up worthless, just as many tech companies from the late 90s lost their value. But that doesn’t mean the movement itself is worthless.

If you strip away the noise, you get to the heart of why this movement matters: crypto is about removing gatekeepers and providing a more efficient and more egalitarian digital economy. Crypto infuses value into the web’s vast networks of information, people, goods, and services.

The second half of this piece focuses on buzzwords related to crypto: Web3, Tokens (Fungible & Non-Fungible), DeFi, DAOs, and Creators.

🕸️ Web3

On the web, the third time’s the charm.

Web1 ran from roughly 1990 to 2005 and centered around information becoming accessible on the internet. Documents and pages were linked together, with companies like Google and Yahoo! making the world’s information easily discoverable. In Web1, most people were passive consumers.

Web2, which has run from around 2005 through today, brought a shift to a participatory web. Rather than passive consumers, we became active creators; the web shifted from a reading platform to a publishing platform. Web2 brought the rise of user-generated content (UGC), which fueled massive platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, YouTube, and TikTok. If Web1 was about information, Web2 was about social connection and content creation.

But Web2 had a dark side: the major platforms vacuumed up all of the economics. The promise of the internet was to cut out the middlemen: instead of being tapped by a studio executive, you could post to YouTube; instead of going through a newspaper editor, you could tweet; instead of signing with a record label, you could upload your music to Soundcloud. But the big internet platforms became the new middlemen. In Web2, users created the value that the platforms then enjoyed.

Web3 is a reorientation of our digital economy. Web3 is the internet (finally) owned by creators and communities. This is made possible through blockchains like Ethereum. Smart contracts run on Ethereum as collections of code with specific built-in instructions—there’s no need for a centralized authority and no intermediaries are involved.

Instead of Facebook owning and profiting from user-generated content, everyday people gain from their own creations. Everyone contributes value to the internet, and everyone enjoys the benefits of that value creation.

I often think of the web’s chronology as:

Consumption ➡️ Participation ➡️ Ownership

And the language of each era matters. In Web1, we browsed. Web2 was about users who were acquired. (The old adage goes: “There are only two industries that call their customers ‘users’: illegal drugs and technology.”) Web3 is about creators and communities who are owners. This is a paradigm shift that rethinks underlying principles: who owns data; who makes decisions; and who reaps the rewards of our collective value creation.

🪙 Tokens (Fungible & Non-Fungible)

Tokens are the lifeblood of Web3: they underpin our new digital economy.

Tokens can be either fungible or non-fungible. Fungible tokens are interchangeable with one another, like dollars in the real world. In last month’s The Deceptive Complexity of Axie Infinity’s Digital Economy, I gave the example of Axie’s two tokens: AXS and SLP. Both are fungible. Star Atlas has similarly outlined a detailed digital economy in its 38-page (!) white-paper:

To use another example, The Sandbox (in some ways “Minecraft for Web3”) has a token called SAND that is the basis for all transactions. The SAND token has particularly strong tokenomics, with three distinct purposes: (1) SAND is a medium of exchange, traded for land and in-game items; (2) SAND is used for governance, with tokenholders able to vote on decisions; and (3) users can stake SAND tokens, earning a share of the platform’s ad and transaction fee revenue. SAND trades today for $2.52, up from $0.04 at the start of the year. With 892,246,119 SAND outstanding, SAND has a market cap of $2.2 billion.

To be technical, tokens like AXS and SLP in Axie, like POLIS and ATLAS in Star Atlas, or like SAND in The Sandbox are ERC-20 tokens. By contrast, non-fungible tokens are ERC-721, a token standard on Ethereum that identifies uniqueness. Most things in the world are non-fungible: your house, your land, your art. NFTs are revolutionary because they inject scarcity into the digital world.

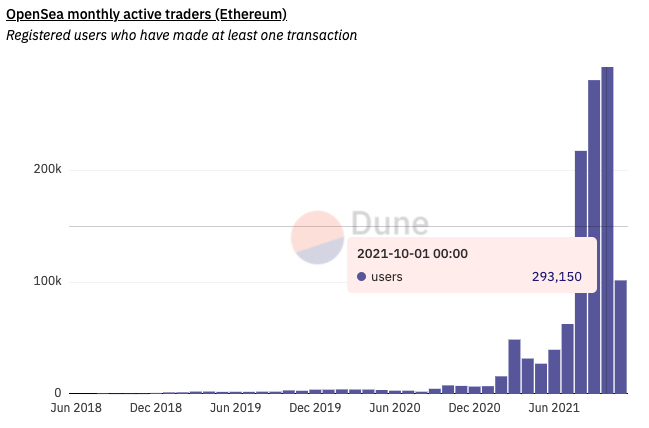

NFTs have exploded in 2021. Trading volume surged to $10.7 billion in the third quarter, +704% over the second quarter. OpenSea has emerged as the go-to destination for buying and selling NFTs, capturing 97% market share. In August, transaction volume on OpenSea grew ~10x month-over-month to $3.4 billion. That’s more volume in a single month than Etsy’s GMV in all of Q2.

OpenSea’s volume has mostly kept pace since August, hitting $3 billion in September and $2.6 billion in October.

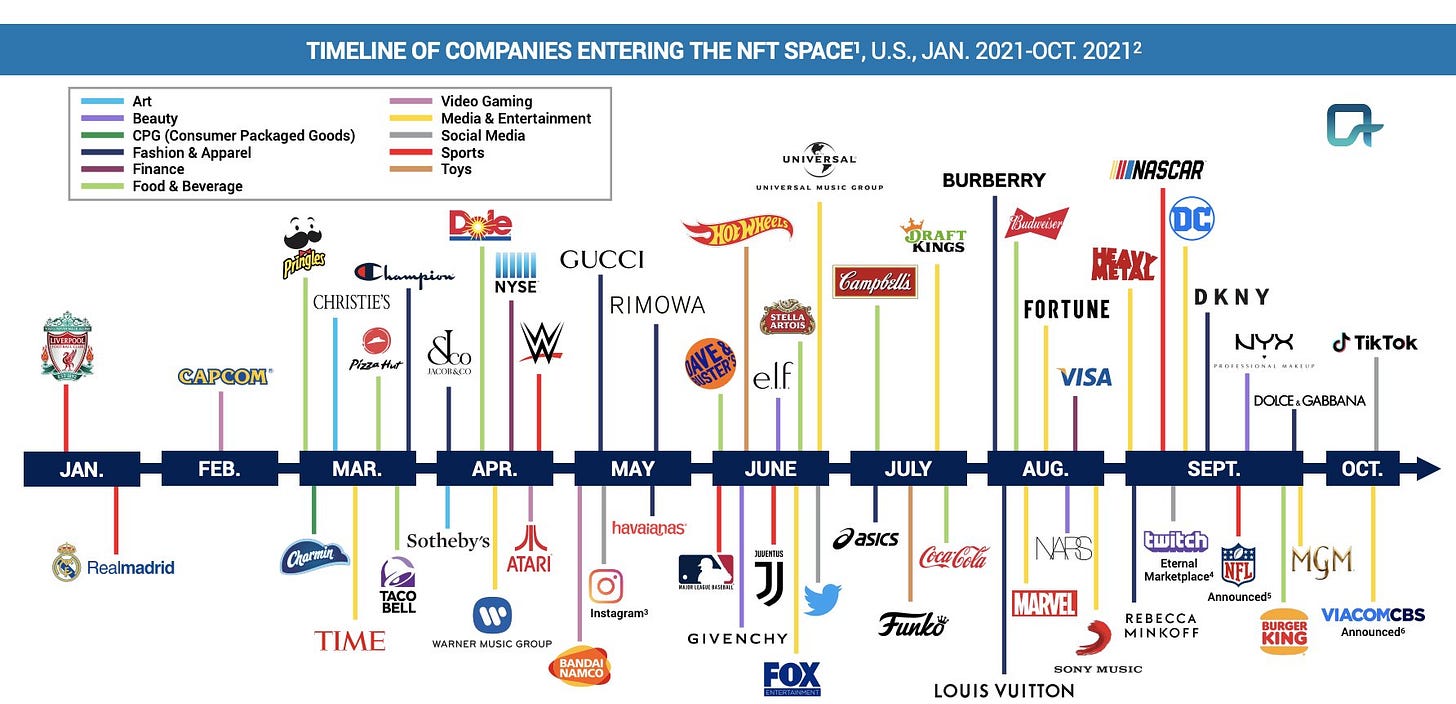

Seeing what’s happening, brands are rapidly entering the NFT space. Everyone from Pringles to Gucci to Burger King has joined in:

Last week, McDonald’s even introduced McRib NFTs 🍔

Slowly, NFTs are seeping into the mainstream with innovative partnerships and use cases. For the upcoming reboot of The Matrix, for instance, Warner Bros. will offer 100,000 NFT avatars for $50 each. On December 16th, NFT holders can choose to take the “Red Pill” or “Blue Pill” and if they choose the “Red Pill”, their avatar will transform into a resistance fighter. Pretty cool.

But despite more companies entering, NFTs remain niche: only 25% of U.S. adults are familiar with NFTs, and only 7% are active users. OpenSea has about 300,000 monthly active traders. By comparison, Ebay has close to 200 million monthly actives. (OpenSea’s October volume implies ~$9,000 of volume per user.)

Volume is concentrated among a small group of crypto enthusiasts: about 70% of OpenSea buyer volume comes from the top 10% of buyers.

The most recent NFT hype cycle was driven by PFP (profile pic) projects. Projects like CryptoPunks, Bored Ape Yacht Club, and Meebits have done hundreds of millions in transaction volume. Having a Punk or an Ape as your Twitter pic is a coveted signal of status in the crypto community.

But PFP projects are traditionally inaccessible to the masses, unless you’re early. There are only 10,000 Punks and only 10,000 Apes. The floor price for an Ape right now (the lowest price you can buy one for) is $155K; the floor price for a Punk is $379K.

Fractional ownership of NFTs, enabled by companies like Fractional, is allowing more people to partake in the NFT market. Fractional ownership also often drives up price. The original image of Doge, the Shiba Inu dog turned into the Dogecoin mascot, was turned into an NFT in June that sold for $4 million. In September, fractional share sales implied a $300 million valuation for the entire NFT.

Essentially any digital asset can be tokenized. Royal, for instance, is a platform that lets fans buy fractional ownership of songs. Fans then earn royalties on those songs.

Say you’re an Adele fan and you believe she’ll be an iconic artist for generations to come. You may have bought a share of ownership in her song “Easy on Me” last month, her first new song in six years. You’ll earn a share of future earnings that the song brings in.

In this way, NFTs are an interesting combination of patronage (support for the artist), fandom (closer connection to the artist), and investment (financial upside from the appreciation of the digital asset).

In Q2, digital art was the killer NFT use case. In Q3, it was PFP projects. What’s next?

I expect utility NFTs to be next, pushing NFTs further toward mainstream adoption. Utility NFTs, as the name implies, provide some underlying utility or application. They could be tickets that unlock exclusive experiences or gaming assets that unlock special powers in a game. Blockchain gaming, in particular, will hit a tipping point. There are many promising companies approaching the space from different angles: gaming studios like Laguna Games; scaling solutions like Immutable; picks-and-shovels like Stardust. Utility NFTs in games may be the mass adoption use case NFTs are waiting for.

Across all of Web3, tokens are being used in new ways to influence behavior. Fungible tokens are becoming the currencies of virtual worlds; NFTs denote ownership and scarcity. Above all, tokens inject incentives into the digital economy. They incentivize creation and consumption, investment and governance. They are the architecture behind the complex economies being built.

💰 DeFi

DeFi is decentralized finance, a blockchain-based form of finance that doesn’t rely on traditional financial intermediaries like brokerages, exchanges, and banks. Fewer industries have more middlemen than finance, and DeFi obfuscates them all.

You don’t need your government-issued ID or Social Security number to use DeFi. By using blockchains—software-based smart contracts—DeFi enables frictionless peer-to-peer transactions with no institution or bank or company facilitating.

At NFT NYC, I overheard two friends arguing over whether DeFi or NFTs will be more impactful.

“There’s over $200 billion of value locked in DeFi,” one said.

“But way more people know about NFTs,” the other countered.

The argument is moot: crypto needs both money and culture. If DeFi ushers Wall Street into a new era, NFTs will do the same for Hollywood, for Fifth Avenue, and for other cultural hubs. Both matter, and both will be massive.

🗳️ DAOs

I kicked off this piece with the buzzword “community”. A DAO is essentially a crypto-native community. I like how Chris Dixon frames it: a DAO is an internet community with a balance sheet. DAO stands for decentralized autonomous organization and DAOs are communities in which the members are in charge.

Tokens are again the lifeblood—they enable access and incentivize action. Early members of a DAO buy tokens to gain access. As the community becomes more popular, tokens appreciate in value and early members are rewarded. DAOs are elegant in that the asset directly reflects the value that the community helps create. Tokenholders also oversee a community-owned treasury and vote on governance decisions. In many ways, DAOs are like an internet-native democracy: the power rests in the hands of the people.

DAOs have become a complex ecosystem with various subcategories. For more detail, Cooper Turley has a good overview of DAO types and offers a market map:

To provide a tangible example, Friends with Benefits (FWB) is one of the most popular and well-known DAOs. FWB is a social DAO—in some ways, you can think of it as a digital Soho House. FWB, which describes itself as “Where Culture Meets Crypto”, writes:

To join FWB, you must hold $FWB cryptocurrency tokens. This means that everyone in the community is literally invested in the community’s success and gets to participate in the upside of the value we create together.

You need 75 $FWB to join the members-only Discord, which currently costs ~$7,000 to ~$8,000. There are also token-gated events for FWB members, including in-person events last week at NFT NYC. And members of FWB vote on key decisions. Even the decision to take VC investment was voted on, passing with 98% of the vote. Instead of a company pitching VCs, VCs had to pitch the community.

This inverted power structure is what makes DAOs so fascinating. DAOs turn the pyramid upside down: power flows bottom-up rather than top-down.

For example, Mad Realities is a DAO-like project that flips the concept of a dating show on its head. Rather than a show’s producers selecting contestants and designing plot-lines, as on shows like ABC’s The Bachelor, Mad Realities puts the community in charge. Buying a Mad Realities NFT means that you get to vote on who is in the show and on what happens. Designed by Devin Lewtan and Alice Ma, the project launched last week and has raised 50 ETH (~$240K) of its 150 ETH target.

Mila Kunis and Ashton Kutcher created the animated show Stoner Cats with a similar concept: you buy an NFT to watch the show and to provide input on the show. If Stoner Cats is the next Family Guy or The Simpsons, tokenholders benefit.

While not full-on DAOs (yet), these examples illustrate the concept. DAOs are about throwing out antiquated power structures, using tokens to align incentives and put the people in charge.

🔨 Creator

During the Index Creator Summit last month, Figma’s Dylan Field and Patreon’s Jack Conte distinguished between creators and the creator economy. Everyone can be a creator with accessible tools, they argued; we all make stuff online. But only when you start earning income from your creations do you become part of the creator economy.

Web2 brought us UGC, which made all of us creators. But it’s been hard to make money off of your work. Web3 changes that. In Web3, it will become easier for us all to be participants in the creator economy—to earn income from the things we make. Instead of earning social capital on your creations—an Instagram like, a Twitter retweet, a new YouTube subscriber—we’ll earn real economic value in the form of tokens.

Creating is like building with legos. A song is a beat, a chord progression, a baseline. A piece of writing borrows from previous ideas and reworks them in new ways. A film fuses images and dialogue and music. The creation of culture involves remixing: we break things down into their atomic units and then assemble them in new ways.

Web3 introduces economic value flows into remix culture.

Imagine this scenario: you make a video of a popular dance trend set to Olivia Rodrigo’s “Good 4 U” that uses an augmented reality filter. In Web3, three creators earn income off of this: the person who came up with the dance trend; Olivia Rodrigo; and the person who originally made the AR filter. Each component part lives on the blockchain and value flows to creators frictionlessly and instantaneously.

The right economic system will expand the market for creators. Today, society devalues creative work—the “starving artist” stigma. In many circles, being an investment banker is more prestigious than being a course creator; being a lawyer is more prestigious than being a podcaster. Building better monetization will help solve this. The best companies and business models expand their markets. The market for digitally-native creative work will grow enormously in Web3.

In What People Misunderstand About the Creator Economy, I wrote about how people misconstrue the creator economy as a vertical trend—as a replacement for Hollywood or a disruptor to media. In reality, being a creator is a horizontal phenomenon. We’ll have doctors and teachers and engineers who are also creators—who earn income in exchange for their specialized knowledge and creative output. The creator economy, at its heart, is a reorientation of how economics flow to the people who make things, rather than being captured by intermediaries along the way.

Final Thoughts

The buzzwords we hear in 2021 are inseparable from one another: expressing ourselves through our avatars will be a critical piece of the metaverse; we need creators to build virtual worlds and we need communities to bring life to them; Web3 and tokens provide the building blocks for vibrant digital economies.

One final example to tie together these thoughts: Loot is an NFT project launched in August by Dom Hofmann, one of the co-founders of Vine. Loot gives players a “bag” of eight pieces of randomized adventure gear. The adventure bag is just eight rows of text:

That’s it. Anyone can then decide what to create with those building blocks.

This is like fan fiction, with economics built in. Imagine if George Lucas hadn’t created Star Wars, but instead gave us the component parts: lightsabers, Jedi, the Millennium Falcon. The community would then be responsible for forging not only one story, but a hundred thousand stories built from the same atomic units. Loot is fascinating because it changes how culture is made. Anyone can buy and sell tokens, anyone can take an economic interest, and anyone can be a creator.

To imagine what the world will look like in 2030 or 2040, you have to think from first principles. The arc of technology bends towards a more equitable, convenient, enjoyable, and affordable future. If you’re providing friction to this inevitable progression, you’re fighting a losing battle. The companies and people who define the next generation will be the ones who lean into this arc.

Sources & Additional Reading

Activate Technology and Media Outlook for 2022 | Activate & WSJ

Zoolander’s 20th Anniversary | Ilana Kaplan

How the Metaverse Is About to Change Everything | Nick Bilton

I enjoyed Naval Ravikant’s and Chris Dixon’s episode on the Tim Ferris podcast

OpenSea’s NFT Bible is a good primer on NFTs

David and Ben at Acquired have a great (3-hour!) podcast episode on the history of Ethereum, as well as an episode on Solana

Two great pieces on DAOs: Mario Gabriele and Cooper Turley

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: