Unbundling College: Technology Is (Finally) Reinventing Education

Uncoupling Learning from Community

This is a weekly newsletter about how people and technology intersect. To receive this newsletter in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Unbundling College: Technology Is (Finally) Reinventing Education

In the opening scene of Netflix’s new show The Chair, the dean of a small liberal arts college gives the newly-appointed chair of the English department (played by Sandra Oh) a piece of paper. It shows that the three highest-paid professors in her department—three tenured old-timers—have the lowest enrollments. They average five students a course. The dean bluntly tells his new chair: get rid of them.

The Chair draws humor from these tenured dinosaurs. One octogenarian professor is stunned that he only has three students show up to his course “Survey of American Letters, 1850 to 1918”, yet he hasn’t bothered to update the syllabus in 30 years. Another professor hasn’t read her teaching evaluations—ever. She burns them in her office waste bin, declaring, “I don’t cater to consumer demands.”

While The Chair is comedic fiction, it captures the state of American colleges in 2021. The bottom line is: college hasn’t changed much in 50 years, and the world has.

More specifically, technology has changed and, with it, the labor market. The slow-moving gears of our education system haven’t kept pace, leading to a system that’s outdated, unequal, and failing learners of the 21st Century.

Covid has thrown these fault lines into stark relief. We’re now entering the third school-year impacted by the pandemic. Parents, teachers, students—everyone is fed up. A year ago, we were talking about a Covid-induced, once-in-a-generation transformation for education. And yet, we’ve slipped into Zoom school; many of the technology solutions for learning act as a band-aid on a flawed system, rather than a fundamental reimagining of how we learn.

The State of the (Education) Union

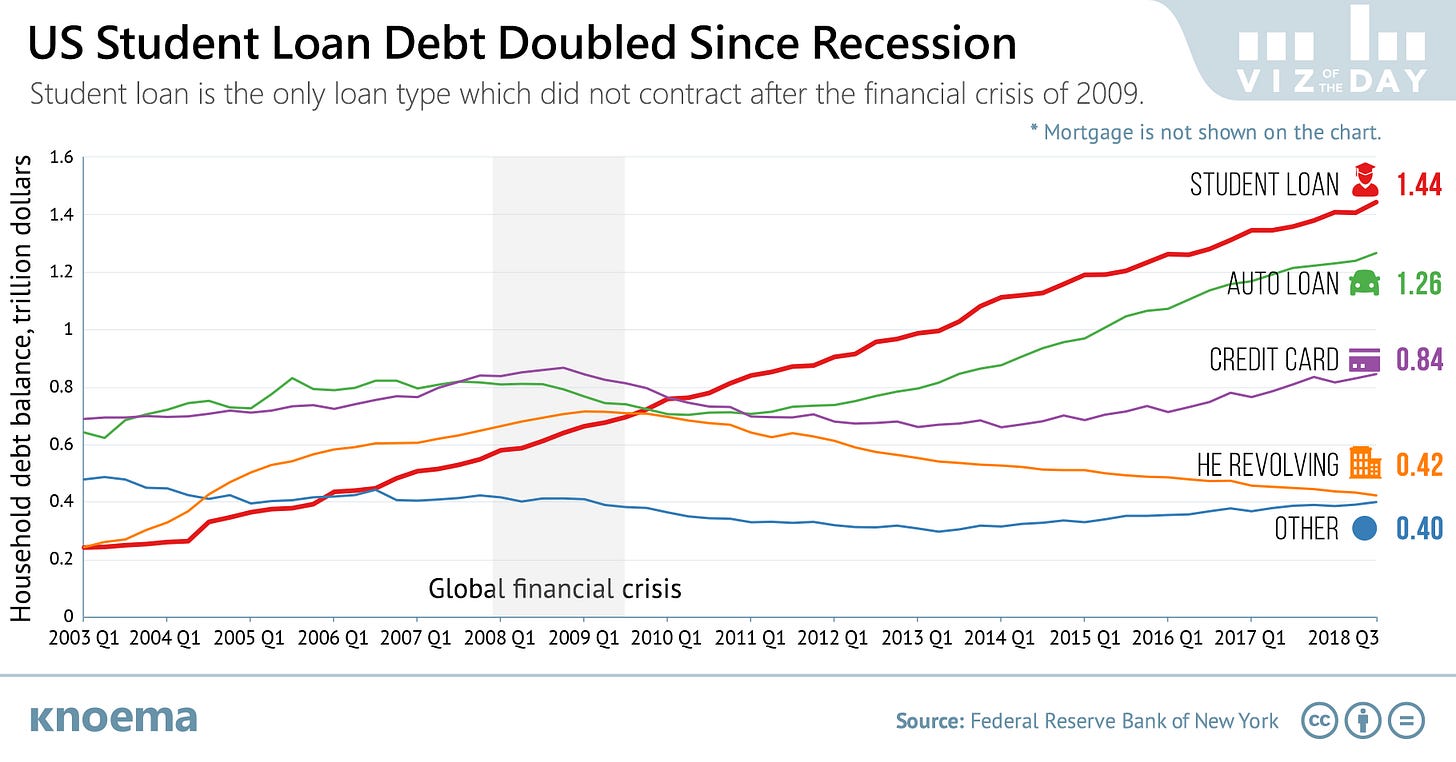

Let’s take a step back. Policy, of course, is partly to blame for education’s lethargy. In fall 2020, I wrote How Technology and Covid-19 Are Reinventing Education and led off with this chart:

This single chart can tell you a lot about American political, social, and cultural shifts over the past 20 years. A $1,000 TV in 2000 might cost you $100 in 2020, but your family’s education, healthcare, and housing costs have soared. The goods and services above the x-axis in the chart are those that form the bedrock for a good life.

Challenges in housing, healthcare, and education can be traced to poor policies: zoning restrictions and NIMBYism (housing), misaligned incentives for quality of care and insurance reimbursements (healthcare), tying school funding to zip codes (education). In a recent podcast, Dylan Field and Marc Andreessen distill the problem down to a supply-demand imbalance. Policy restricts supply—for instance, San Francisco only builds 6,000 (!) new housing units a year. Restricted supply increases prices, so policies are created to subsidize demand; subsidized demand in turn increases prices, and you’ve got a vicious cycle of ever-escalating costs.

Skyrocketing costs of education—the cost of education is growing 8x faster than real wages—have led to a student debt crisis. Americans own $1.5 trillion of student debt—the largest category of non-housing debt in America. And unlike other forms of debt, student debt is nearly impossible to discharge during personal bankruptcy.

Education startups have often run into the buzzsaws of government bureaucracy, thin budgets, and sluggish sales cycles. But education is an attractive market: it’s a $1.6 trillion market in the U.S. ($4.7 trillion globally) and the nation’s second-largest sector by employment, behind only healthcare.

And the problems aren’t going away. Technology will displace millions of jobs over the coming decades, while creating demand for entirely new types of work: 85% of today’s college students will have jobs in just 11 years that don’t currently exist. This requires worker reskilling and yet, only 0.1% of GDP is spent on helping workers retrain—less than half of what was spent 30 years ago. Today’s dual impacts of Covid (a short-term shock) and a rapidly-changing labor market (a long-term shift reaching its zenith) make innovation in education more urgent than ever.

Unbundling College

For many Americans, college is about finding a good job. But for millions of others, college isn’t about the education; it’s a rite of passage.

A piece by Ian Bogost in The Atlantic put it best:

Quietly, higher education was always an excuse to justify the college lifestyle. But the pandemic has revealed that university life is far more embedded in the American idea than anyone thought. America is deeply committed to the dream of attending college. It’s far less interested in the education for which students supposedly attend.

[Education] is just a small part of college’s purpose. In the United States, higher education offers a fantasy for how kids should grow up: by competing for admission to a rarefied place, which erects a safe cocoon that facilitates debauchery and self-discovery, out of which an adult emerges. The process—not just the result, a degree—offers access to opportunity, camaraderie, and even matrimony. Partying, drinking, sex, clubs, fraternities: These rites of passage became an American birthright.

This is the depiction we get from Hollywood: think Animal House (“Toga! Toga!”) or Old School (cut to a shot of Will Ferrell doing a keg stand). Even Monsters University—a Pixar movie!—is about monsters pledging a fraternity called Roar Omega Roar. I mean, come on. College has become less the place to acquire skills for the workplace, and more the cocoon to facilitate debauchery and self-discovery.

In addition to being a rite of passage, college is more than ever about signaling. We can see this in something called “the sheepskin effect”. The sheepskin effect shows that degrees, rather than skills, determine income. If you go to Stanford and drop out after seven of eight semesters, you’d theoretically expect to earn 7/8 the income of a Stanford graduate; after all, you learned 7/8 of the skills. But instead, you can expect to earn 50% as much. That final eighth doesn’t deliver half the learning; instead, completing the degree is a signal to employers.

Over the next 10, 20, 30 years, college will become steadily less important. The story of the next decades will be an unbundling of college—an uncoupling of learning and community.

Young people are more pragmatic: 89% of Gen Zs have considered a path other than college. The combination of crushing student debt and anti-institution sentiment (working within “the system”) make college less attractive. Gen Zs care about learning real skills and then turning those skills into tangible income. I’ve used the example of this TikTok before, but it captures the Gen Z mentality. One woman asks, “What’s something that’s not a cult but borderline seems like one?” A man replies:

“That would be like 98% of the United States population that has been brainwashed into believing that it’s normal to give up 5 out of every 7 days of your week just to make someone else rich for 40, 50 years doing something you don’t even actually enjoy just to get 10 years of freedom before you’re too old to actually enjoy it.”

The dream of college that we’re sold fits into this worldview. But where Millennials are idealistic, Gen Zs are practical. We’ll see more young people eschew college in favor of vocational schools, online degrees, or alternative forms of education. A crop of new startups will offer the “learning” piece of the college bundle.

Forage, for instance, offers students free work programs with companies. Students can showcase their skills and employers can hire people with the right skills for the job. The World Economic Forum estimates that closing the skills gap could add $11.5 trillion to global GDP by 2028; Forage’s mission is to help close that gap.

Outlier makes your typical “college education” more accessible, lowering costs by 80% with online courses from places like the University of Pittsburgh and offering full refunds to students who do the work but don’t pass.

Learn In offers companies “upskilling-as-a-service” by letting employees take “learning sabbaticals” to refresh skills. Upskilling internal talent is 33% less expensive than hiring externally, and helps with employee retention.

Companies like Lambda, Flockjay, and Microverse are pioneering income-share agreement models to make learning more accessible, while stalwarts from the MOOC (massive open online course) era of education like Coursera, Udemy, and Udacity continue to grow. Each is tackling the “learning” piece of college.

On the “community” side, young people are socializing and meeting strangers online; Fortnite’s Battle Royale and niche subreddits are the new fraternities and sororities. For learners who turn to non-college solutions for job readiness, digital realms will provide the community once delivered by college.

Of course, some of the most interesting education companies combine “learning” and “community” in new ways. Outschool, a marketplace for live online courses, lets small groups of kids bond over shared interests. Prendea is doing the same for learners in Latin America. With Kajabi or Maven, creators can launch online courses and reach a vibrant community. There’s a massive opportunity for cohort-based courses to inject community into online learning, using social cohesion and accountability to fix the low completion rates that have plagued MOOCs for the last decade.

And some of the most formidable modern education companies—on both the learning and community side—don’t look obvious. As comments in TikTok constantly remind me, TikTok is the defining education company of our time.

In How Neopets Paved the Road to the Metaverse, I wrote about how Neopets taught a generation how to use HTML to make webpages. Millions of kids today effectively learn to code by playing Minecraft. Minecraft requires users to learn concepts like AND and OR gates, and to figure out that commands like “/time set 0” reset the time in the game to daybreak. Users self-teach these concepts and then use them to build vibrant and complex worlds, like replicating King’s Landing from Game of Thrones:

One 12-year-old playing Minecraft decided he needed a better weapon. So he scoured internet forums and YouTube tutorials (for much of the 2010s, “Minecraft” was the second-most-popular search term on YouTube after “music) to learn what to do. Then he typed: “/give AdventureNerd bow 1 0 {Unbreakable:1,ench:[{id:51,lvl:1}],display:{Name:“Destiny”}}.” The command resulted in a magic, unbreakable bow-and-arrow called Destiny.

Platforms like Minecraft are subtly powerful education tools—ones that combine both skill-building and socialization. Digital-native learning tools (often in disguise) will become more relevant. In five years, a job applicant might present a prospective employer with the Minecraft world she built instead of sharing her college transcript.

Final Thoughts

We’re at an inflection point. Gen Z’s coming-of-age is colliding with a once-in-a-century pandemic, while more of the world comes online. The next generation of learners is faced with crushing student debt, unequal access to education, and rapidly changing skills demanded by the workforce.

And yet, our education system has barely seemed to notice. You know a system is broken when nearly every participant is suffering, but the incumbents effectively shrug. (One is reminded of the professor’s words from The Chair: “I don’t cater to consumer demands.” Well, maybe you should!)

During the beginning of the pandemic, a joke made it’s way around Reddit and Twitter:

The status quo is untenable. We’re overdue for a sea change in education.

Over the next 20 years, I expect college attendance to go down. Little will change for the Harvards and Stanfords of the world—signaling will be as prevalent as ever—but millions of learners will forego mid- and lower-tier colleges (and especially non-STEM programs) in lieu of vocational schools, online education, or other forms of job credentialing. The most successful startups will circumvent the slow and quixotic sales cycles of schools by selling direct-to-learner or by arming enterprises with tools to upskill their workforces.

At the same time, we’ll see a shift to lifelong learning: education won’t be a lump-sum consumed in the first ~20 years of life, but something we all sporadically consume throughout a career. The pace of technological change will necessitate it. This is why I prefer the term “learning” to “education”—it connotes something living and breathing and evolving, rather than something static.

For most people, college won’t be something that takes place on a campus, or that fulfills a rite of passage, or that resembles Animal House. The two components of college—learning and community—will both happen in the digital realm.

Sources & Additional Reading

The Question of Education | Marc Andreessen and Dylan Field

College Was Never About the Education | Ian Bogost, The Atlantic

Unbundling Harvard | CB Insights

The Minecraft Generation | Clive Thompson (one of my favorite reads of the past few years—teaches you so much about how young people use technology)

Related Digital Native pieces:

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive this newsletter in your inbox each week: