Viral Growth: How to Keep Lightning in the Bottle ⚡️

In a World of Rising CACs, Exploring Growth Engines and Viral Boosts

Weekly writing about how technology shapes humanity, and vice versa. If you haven’t subscribed, join 40,000+ weekly readers by subscribing here:

Viral Growth: How to Keep Lightning in the Bottle ⚡️

Last week, the forthcoming Barbie movie—starring Margot Robbie as Barbie and Ryan Gosling as Ken—unveiled a brilliant marketing campaign. Anyone could visit the website barbieselfie.ai and create their own version of the movie’s poster, just like the film’s stars:

Here’s my version, which I made for a tweet about this marketing strategy:

Of course, the Barbie poster phenomenon was immediately meme-ified across the internet. Nearly every recent pop culture moment got the Barbie poster treatment:

The campaign is genius in its inherent virality—it’s accessible, it’s simple, it’s easy-to-understand. Most importantly, it can be remixed endlessly. It will generate massive buzz and awareness for the July 21st film.

In my mind, this is the savviest movie promotion since 2008’s The Dark Knight. For that film, Christopher Nolan hired an agency called 42 Entertainment to produce a year-long real-world experience (known as an ARG, or “Alternate Reality Game”) that got 11 million people to participate across 75 countries. Millions took to the streets in support of Gotham’s fictional district attorney Harvey Dent (their signs read “I Believe in Harvey Dent”) while 650,000 took part in a complex Joker-themed scavenger hunt.

The Dark Knight went on to smash box office records for opening weekend.

Savvy marketing fuels commercial performance.

This is true in box office, and it’s true in startups. Virality has always fascinated me. In a world of abundance, how do products catch fire and spread rapidly through society and culture? Virality is an art (can you tap into the zeitgeist?) and a science (can you design a product that embeds viral loops?).

Startups need virality; they need to reach escape velocity. The venture model is built on this premise. I often think of a quote from Paul Graham:

“A startup is a company designed to grow fast. Being newly founded does not in itself make a company a startup. Nor is it necessary for a startup to work on technology, or take venture funding, or have some sort of ‘exit.’ The only essential thing is growth. Everything else we associate with startups follows from growth.”

Startups can rely on paid growth, of course—performance marketing. Many technology companies grew primarily through paid channels—Booking.com in travel, Wish in e-commerce, Credit Karma in fintech. About half of Uber’s growth in the 2010s was paid, and about half was driven by word-of-mouth among drivers and riders.

Paid acquisition can get you a long way: the most famous example from recent years is TikTok. Bytedance, TikTok’s Chinese parent company, spent $3M per day in 2018 on paid acquisition—about $1B for the full year. At one point, TikTok was Snap’s biggest advertiser (before Snap realized that TikTok was siphoning its users and that it had been effectively selling nuclear weapons to the enemy).

We see the paid acquisition playbook happening again right now. The discount e-commerce app Temu has topped US charts for much of the past few months; behind the scenes, China’s Pinduoduo ($85B market cap) is plowing millions of dollars into Temu ads. And Bytedance is quietly executing its TikTok playbook again, pushing Lemon8 on young consumers. Lemon8 is effectively a Gen Z mash-up of Instagram and Pinterest—it’s actually most similar to the popular Chinese app Xiaohongshu, or “Little Red Book”—and it’s been downloaded 650,000 times in just the past week and a half. Lemon8 currently sits 28th in the App Store, and it looks set to break into the top 20 soon.

Of today’s top 20 apps, 10 are owned by just three companies—Bytedance (TikTok and CapCut), Meta (Instagram, Facebook, WhatsApp, and Messenger), and Google (Google, YouTube, Gmail, and Maps). The rest are a smattering of other familiar Big Tech and almost-Big-Tech names: Amazon, SHEIN, Snapchat, Cash App, Roblox.

It’s been a while since we’ve seen a startup linger in the top 10 for more than a few weeks. Much of this comes down to distribution.

Most startups don’t have the backing of an internet giant to fuel growth. And paid growth is becoming much, much more difficult. A direct-to-consumer brand used to be able to scale to $20M, $30M, or even $40M in revenue on Facebook ads alone. Despite its poor reputation, Facebook’s ad engine is actually quite egalitarian for small businesses and fledgling companies; using Facebook, those smaller players could reach customers just as efficiently as multi-billion-dollar companies. In the mid-2010s, we saw a proliferation of DTC brands built on the back of Facebook—they offered us mattresses and meal kits, cosmetics and underwear, shoes and suitcases.

This playbook is monumentally more difficult in 2023: Apple’s ATT changes have made it much more difficult to scale and measure digital advertising spend.

There’s an entire generation of DTC startups that wouldn’t work today. Rather than scaling to ~$40M on Facebook, a brand might hit $1M or $2M in sales, then see its ROAS (Return On Ad Spend) begin to deteriorate. It would then need to find other channels. Attribution platforms like Northbeam and Triplewhale help, but they can’t fix the root of the problem.

With performance marketing becoming more difficult, startups need to figure out virality. Virality is the holy grail for startups, and it’s the focus of this week’s piece. (I’ll do a future piece on paid distribution channels.)

I tend to group virality into two buckets:

Built-in Virality: This is virality embedded in a company’s business model or product.

Viral Boosts: These are one-off “boosts” that drive growth, but that aren’t intrinsic to the business / product.

The analogy I think of—though somewhat silly—is Mario Kart. Built-in virality is the vehicle you select; it’s the engine, and it’s core to your business / product. Viral boosts, meanwhile, are Mario Kart’s growth boosts (for the uninitiated player, you collect coins that you can then spend on boosts to deliver speed and acceleration). Boosts are short-lived, but incredibly helpful.

Dan Hockenmaier and Lenny Rachitsky have a more in-depth racecar analogy in their excellent Reforge course (worth checking out) but I’ll keep things simple here with just the two components. I’ll also keep the Mario Kart analogy given that it’s timely: The Super Mario Bros. Movie is smashing records in theaters right now.

We’ll tackle boosts first, which tend to be more creative and experimental, and then we’ll turn to the core growth engines that are fundamental to startup success.

Let’s jump in 🏎

Viral Boosts

I have a soft-spot for creative growth hacks. There’s so much noise out there; breaking through it—and doing so consistently—is an art form.

Earlier in my career, I worked on the growth team at Calm, the mental health app. Though Calm grew primarily through performance marketing, the team was consistently brilliant at creating viral moments. Virality was in the company’s DNA from the start: in 2011, Alex Tew, Calm’s co-founder, created a website called donothingfor2minutes.com. If a visitor to the website could manage to stare at an image of the sunset for two minutes—without moving her mouse or touching her keyboard—she would get a prompt asking for her email address. The site went viral, and Calm collected 100,000 emails pre-launch. (The donothingfor2minutes.com domain still works and is still owned by Calm.)

Over the years, Calm has kept up its viral moments. I wrote about these moments in last year’s Revisiting Lifetime Value and Customer Acquisition, but two examples: When La La Land was generating Oscar buzz, Calm (famous for its Sleep Stories) put out the spoof Baa Baa Land—an 8-hour film of sheep grazing, marketed as “the dullest movie ever” and promising “the ultimate insomnia cure.” Then in 2020, Calm sponsored the anxiety-ridden Presidential Election coverage on CNN. Tongue-in-cheek, ironic, and brilliant.

This gets at a bifurcation of viral boosts: there are boosts that help you get going, solving the cold start problem. These boosts might get you your first 100 or 1,000 users. And then there are boosts that you use later on, once you have momentum.

The first type of boosts—the “getting off the ground” kind—are what we think of when we tell startups to do things that don’t scale. The canonical example now is the Airbnb story: Airbnb’s founders were strapped for cash, and the business wasn’t taking off. This was right around the 2008 election. So the founders designed fictitious cereals called Obama O’s (“Hope in every bowl!”) and Cap’n McCain’s (“A maverick in every bite!”). They printed off the images and assembled the boxes; Brian Chesky remembers, “I was thinking at the time that Mark Zuckerberg was never hot-gluing anything at Facebook—so maybe this is not a good idea.” They mailed boxes to prominent journalists, and the cereal was a hit; news coverage of the stunt generated tremendous earned media value (a fancy way of saying free coverage, or “buzz”).

Some “boosts” jumpstart virality in a less-viral, more manual way. Tinder, for instance, went to college campuses and signed up sorority girls; the founders knew that if they got the girls, the boys would soon follow. Hipcamp, a marketplace for camping and RV parks, got its first 100 users by setting up a folding table in front of REI stores. (Lenny Rachitsky has an excellent post on how dozens of companies got their first users.)

Other startups have leaned into viral content. Dollar Shave Club’s famous “Our Blades Are F***ing Great” video has 28M views on YouTube. The language-learning app Duolingo took off when its founder gave a viral TED Talk that led to 300,000 people signing up for the private beta.

Duolingo is a great example of a company that has maintained its virality well past its launch. I would crown Duolingo the savviest brand on TikTok 👑 The app’s mascot, Duo, is everywhere. He has his finger wing on the pulse of the zeitgeist; rarely does he miss a pop culture moment. Just this week, Duo made the journey to Cornelia Street to mourn Taylor Swift’s break-up with Joe Alwyn. (One of Swift’s best love songs about Alwyn is called “Cornelia Street”.)

My favorite recent example of Duolingo’s TikTok brilliance: an April Fool’s parody about a new dating show called Love Language. The premise of the show is that 10 “confident and flirty singles” from across the globe come together “to share a house in paradise in hopes of finding true love.” The catch: None of them speak the same language. The trailer for the fake Peacock show is hilarious.

The contestants of course use Duolingo to learn each other’s languages, with disastrous results.

This sort of content is brilliant; it’s destined to go viral. And the trailer for the show did go viral, amassing 12.2M views on TikTok. Not bad, Duo.

Some established brands are also savvy at viral boosts. Chipotle consistently goes viral on TikTok with challenges like the #LidFlipChallenge and #GuacDance. Burger King comes up with genius campaigns, like one of my go-to favorite viral stories: the time Burger King announced it would offer 1-cent Whoppers to any smartphone user within 600 feet of a McDonald’s. Within a week, the campaign drove over 1M downloads of the Burger King app, and the app went from #400 to #1 on the App Store.

These campaigns create massive earned media value. In other words: they create buzz.

Three steps to executing viral boosts:

Hire young people,

Experiment,

Double down on what works (including putting dollars behind viral content).

Earlier this year, I wrote about 20-year-old Mary Clare Lacke, an intern at Claire’s, the teen accessories retailer that was once the go-to place for any 90s-baby looking to get her ears pierced. Claire’s revenue declined throughout the 2010s as the brand struggled to stay relevant in the digital age. One of Lacke’s tasks as an intern: inject fresh energy by running Claire’s nascent TikTok account.

In an 11-second video, Lacke riffed on a TikTok trend called “krissing”—a bait-and-switch type of video, inspired by Kris Jenner, that misleads the viewer and then reveals the fake-out. Lacke used #krissing to reveal that Claire’s did indeed still sell gummy bear earrings. The video generated 1.5 million views and 20,000 new followers for the company’s TikTok account.

This story speaks to a new phenomenon: the rise of the Gen Z TikTok intern.

Mary Claire Lacke is now one of four TikTok “college creators” that work for Claire’s as interns during the school year, producing new TikTok videos each week. Other brands are following suit, leveraging young people’s digital fluency to stay relevant.

Cisco is now offering to train all 83,000 of its employees to act as influencers, even letting them take over corporate socials for a day. United Airlines has a team of 50 in-house influencers. Everyone is looking for virality—for a breakthrough customer acquisition moment.

To close this section, I asked Matt Moss, the founder of Locket, for a few TikTok tips. Locket is an app that lets you embed photos from friends into your phone’s homescreen—sort of a digital photo album. You can send your friends Locket photos that update automatically. Matt started Locket as a way to stay close to his long-distance girlfriend—they’re pictured here:

Upon launch, Locket went viral, hitting #1 in the App Store and amassing 20 million downloads and 1 billion photo shares in its first few months.

No one gets TikTok virality like Matt, so I asked him to share a few words of wisdom:

“TikTok growth, when it’s really working, is actually word-of-mouth growth amplified times a million. It’s the same energy as a kid telling their friend at school about an app, but instead of that leading to one person hearing about the product, it could reach 10 million people.”

“Authenticity is super important. A genuine video of someone using the product is much better than a highly-produced video.”

“Our early users started making their own TikToks about the app in the same style as our original launch video. This is what really drove the app’s initial growth—early users who loved the product wanted to show off how they were using it.”

“Telling a story about the creation of the product is great for authenticity. Some of our best-performing videos just explain how and why the app was originally built.”

“It’s really helpful if the product allows the user to express themselves in some way. This way, when they’re creating a TikTok about the product, it’s 50% about the product and 50% about them as a person.”

Built-in Virality

Viral moments—like those above—are somewhat dependent on luck. There’s hard work and creativity involved, sure, but marketing is fickle; you never know how people will react. Building virality into a product, though, isn’t a function of luck; virality is engineered.

Many of the best companies have growth loops—flywheels that spin faster over time. Here’s Amazon’s famous growth loop:

Low prices attract customers. Customers attract sellers. More sellers improve selection, which in turn improves the customer experience. Growth leads to a lower cost structure, which drives prices down even further.

One of my favorite flywheels is that of Faire. I’ve written about Faire in the past—it’s where my partner Ian works—and I went deep on it in The $100 Trillion Opportunity in Marketplaces. But essentially, Faire is a B2B marketplace connecting retailers and brands. Picture any cute, local shop on Main Street; it probably sources its inventory through Faire’s marketplace.

The key to Faire’s exponential growth is referrals. Here’s a graphic from Anu Hariharan at YC Continuity that captures it well:

Incentives go beyond the benefits in this graphic—they’re also financial:

Say that Rachel, a retailer behind Rachel’s Boutique, already works with a dozen brands. For every brand that Rachel refers to Faire, she gets a shopping credit. Faire also won’t take a commission on that brand-retailer relationship. The platform is designed so that everyone wins. Brands want all their retailers on the marketplace, because they benefit from managing their entire business all in one place. Retailers benefit because they get access to free returns, net-60 payment terms, and better shipping rates. Incentives turn the flywheel faster.

Many other marketplace startups have relied on referrals; referrals are an excellent way to ignite viral growth. In the early days, Uber offered you $10 for referring a friend:

Airbnb, for its part, offered $25 in travel credit for referring a guest and $75 in travel credit for referring a host. According to Airbnb’s Gustaf Alströmer, referrals outperformed every other channel upon launch, growing 900% year-over-year.

The startups best positioned for viral growth—and thus well-positioned for venture dollars—often have a network effect component. To use the Faire example: as more retailers and brands join the platform, the marketplace becomes more valuable to both sides. Same for Uber with drivers and riders, and for Airbnb with guests and hosts.

But you don’t need to have network effects to benefit from well-executed referrals. Duolingo is largely a single-player language learning app, but grew meaningfully through incentivized referrals. And Calm has one of the best-designed referral programs out there; from Growth Design’s case study of Calm’s product:

Calm also gives users the opportunity to share their experience with friends via Instagram Stories and iMessage. They subtly encourage virality.

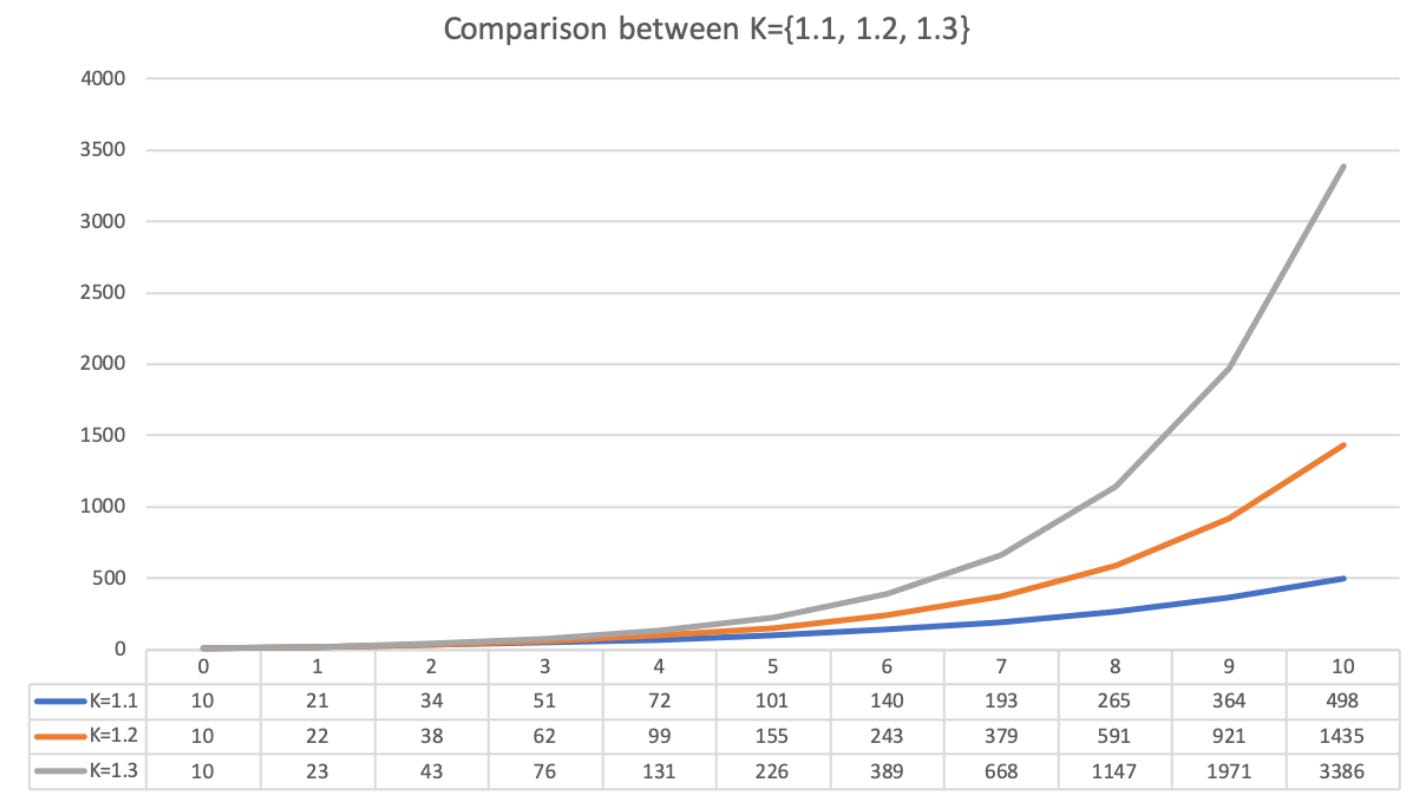

One measure of virality is the k-factor, or the number of new users that each user brings. When the k-factor is greater than 1, the product grows virally. You can see in this chart that small changes in k-factor lead to massive differences in growth; again, the power of compounding.

A 20% change in k-factor leads to 6.8x more users after 10 time periods.

The rise of real-time collaboration and product-led growth brought virality to enterprise software. My friend Badrul Farooqi was Figma’s first PM. He remembers:

“When Figma launched, designers were using several different products to design, build design systems, create prototypes, organize files, and, finally, collaborate with stakeholders. Figma solved many of these problems by providing a single, streamlined experience.

“We focused on providing designers with an experience that they’d never had before: a single source of truth to design and work with others. This experience was so important that it ultimately became the core activation metric: collaboration in the same file with someone else within 24 hours. Specifically, editing or commenting in a file after another user edits or comments in a file. Once this happens, we consider both users activated.

“This allowed us to focus on the customers we really wanted to win: designers who worked on teams. We also found that those who experienced this aha moment were much more likely to continue using Figma and become paying customers.”

Inviting collaborators is built-in virality. You see a similar effect in software products that require multiple users: Calendly, for instance, for calendar management, or Zoom for video calls. Both spread virally. (One call-out to be careful of in viral enterprise products: charging the collaborators people bring in. Many SaaS companies have gotten in trouble for sending a surprisingly large bill. Figma handles this well: new editors can be invited for free at any time. Admins get an email before payment each month that summarizes the bill and any new editors, giving admins the opportunity to downgrade editors to viewers and avoid extra costs.)

Similar viral dynamics are seen in social features. Facebook, of course, pioneered the social network effect: the more friends you have on Facebook, the more valuable the product to you. But startups that aren’t social companies at their core can still leverage social features. Snackpass is an order-ahead app for take-out food—in some ways, you can think of it like the Starbucks mobile app for every restaurant.

Founded by Yale students, Snackpass went viral on Yale’s campus thanks to its social features: users could “gift” each other food. You might send your crush a boba tea, prompting her to download the app to accept the gift.

I asked Kevin Tan, Snackpass’s founder, how they came up with the idea:

“Snackpass started out single player (order ahead and get discounts). Users liked the value they were getting, but word wasn’t spreading as fast as we liked. We asked ourselves how we could incentivize users to share their experience with their friends without spending a boatload on referrals—at the time we were entirely bootstrapped.

“We found a win-win-win between the merchants, the customers, and the platform. With every order, users have the option to gift a point to a friend. This not only increases savings for the user, but also provides marketing and exposure for the merchant, and boosts word of mouth for the platform. Even more than just savings, it evolved into a fun and casual way to connect with close friends.”

Virality doesn’t need to be expensive; it can come down to smart product decisions.

Final Thoughts

There are many creative ways to grow your business. Some are rather unorthodox. Michelin, the tire company, launched the Michelin Guide to Michelin Star restaurants in an effort to get French motorists to drive around Europe looking for good food (thus wearing down their tires). It’s hard to get more out-of-the-box than that.

But there are also playbooks to follow. Most fundamentally, build virality into your product. Having a network effect or being a multi-player product help, of course, but they’re not necessary. See the examples of single-player products like Duolingo and Calm above. Apple is neither a marketplace nor a social network, but figured out clever ways to grow: over two billion iPhones have shipped with the default email signature “Sent from my iPhone.” (Email products like Superhuman and Gmail have followed suit.)

There’s no substitute for embedding virality into the product and business model. That’s the sustainable growth engine. But one-off boosts help. Who knows how many app downloads Duolingo’s Love Language spoof generated—but the stunt created buzz, earned media value, and word-of-mouth. Hiring a Gen Z TikTok intern will probably pay for itself many times over.

This summer, I’ll do deep-dives into additional distribution channels, interviewing some of the leading experts in the space. But there’s nothing quite like viral growth. When you can nail it—either in your product or as a marketing campaign—it’s magic.

Sources & Additional Reading:

I enjoyed Dan Hockenmaier’s and Lenny Rachitsky’s Reforge course, including their racecar framework—it goes into more detail on growth channels (and you get even more car analogies!). Their piece for First Round review is also good.

As mentioned above, Lenny also has some great pieces on how startups grow

Casey Winters has excellent writing on this as well, such as this piece on building content loops

I’ve always enjoyed Sarah Tavel’s writing on marketplaces and growth loops

The Rise of Gen Z TikTok Interns | NYTimes

Thank you to Badrul Farooqi (Figma), Matt Moss (Locket), and Kevin Tan (Snackpass) for contributing here

Related Digital Native Pieces

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: