Welcome to the Internet: Millennial & Gen Z Ennui

How the Internet Influenced a Generation's Worldview

This is a weekly newsletter about how tech and culture intersect. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Welcome to the Internet: Millennial & Gen Z Ennui

Almost exactly a year ago—on May 30, 2021—Bo Burnham’s Netflix special became an unexpected sensation. Burnham’s special, titled Bo Burnham: Inside, is unique in that it was recorded entirely in the guest house of Burnham’s L.A. home during COVID, without a crew or audience. As a result, Inside became emblematic of our pandemic life: the title itself alludes to the fact that we’re all, quite literally, stuck inside.

But the title also alludes to being inside of Burnham’s mind. And as viewers, we are: the entire special was pulled off by one man’s sheer will (with a little help from a producer), performed alone in his home during a global pandemic.

What fascinates me about Inside is how it perfectly captures the life experience of a digital native. Burnham is a Millennial, and his special will resonate most with those of us who remember AIM and MySpace and AskJeeves. (There’s even a song about turning 30.) But his material will also strike a chord with a younger generation that doesn’t remember 9/11 and that has never known a world without social media. In many ways, the entire special is a commentary on our collective love-hate relationship with the internet.

The commentary starts out innocently enough. One of the opening numbers is a (very catchy) song called “White Woman’s Instagram” that makes fun of…you guessed it, white women on Instagram. A sample verse:

Latte foam art, tiny pumpkins

Fuzzy, comfy socks

Coffee table made out of driftwood

A bobblehead of Ruth Bader Ginsburg

A needlepoint of a fox

Burnham paints a picture of your stereotypical white woman’s very curated, very basic Instagram grid, even going so far as to create the photos he imagines she would post:

Not bad.

The song “Welcome to the Internet” goes on to capture the frenetic chaos of the internet. I often reference what happens in “an internet minute”—5.7M Google searches, 694K hours streamed on YouTube, $283K spent on Amazon, 12M iMessages sent. At Index, we often talk about Discord’s 19 million weekly active servers as being representative of the internet; there’s a place for everyone. Burnham packages this chaos into song:

Welcome to the internet

What would you prefer?

Would you like to fight for civil rights or tweet a racial slur?

Be happy

Be horny

Be bursting with rage

We got a million different ways to engage

The hook “Could I interest you in everything, all of the time?” encapsulates the internet—vast, uncharted, overwhelming, unending.

As Inside continues, the internet becomes less cute and funny, and more sinister. You can already see this in “Welcome to the Internet” with lines like “Would you like to fight for civil rights or tweet a racial slur?” nodding to the internet’s double-edged sword—a force for good and a weapon for hatred, all at the same time.

Burnham’s most viral song—the one that had the most legs in the zeitgeist—is his ode to our lord and savior, Jeffrey Bezos. If you don’t occasionally find yourself singing, “CEO, Entrepreneur, Born in 1964, Jeffrey, Jeffrey Bezos” you don’t spend much time on TikTok. TikTok adopted the Bezos song as an anti-capitalist mantra, and Burnham’s point isn’t far off: he’s signaling that we’ve become pawns to our internet overlords.

Burnham himself has a complicated history with the internet. He became famous on YouTube, way back in 2006 as a 16-year-old, and without the internet he wouldn’t be making a Netflix special for millions of people to see. But Burnham is also candid about the toll the internet has taken on his mental health. More broadly, Inside is about the fraught relationship we all have with technology and our mental health.

The special concludes with its two most somber numbers, and it’s these that capture Millennial and Gen Z ennui.

In “All Eyes On Me” (which went on to win a Grammy), Burnham sings about his personal mental health and his generation’s collective mental health crisis. The song explodes with the incredible line “You say the ocean’s rising like I give a shit” which, in referencing climate change, embodies young America’s sheer exhaustion.

This is the generation that grew up with 9/11 and the Iraq War, with student loan debt and income inequality, with the 2008 recession and the 2020 pandemic. They have to contend with Ukraine and wildfires and school shootings and Mitch McConnell. They’re tired.

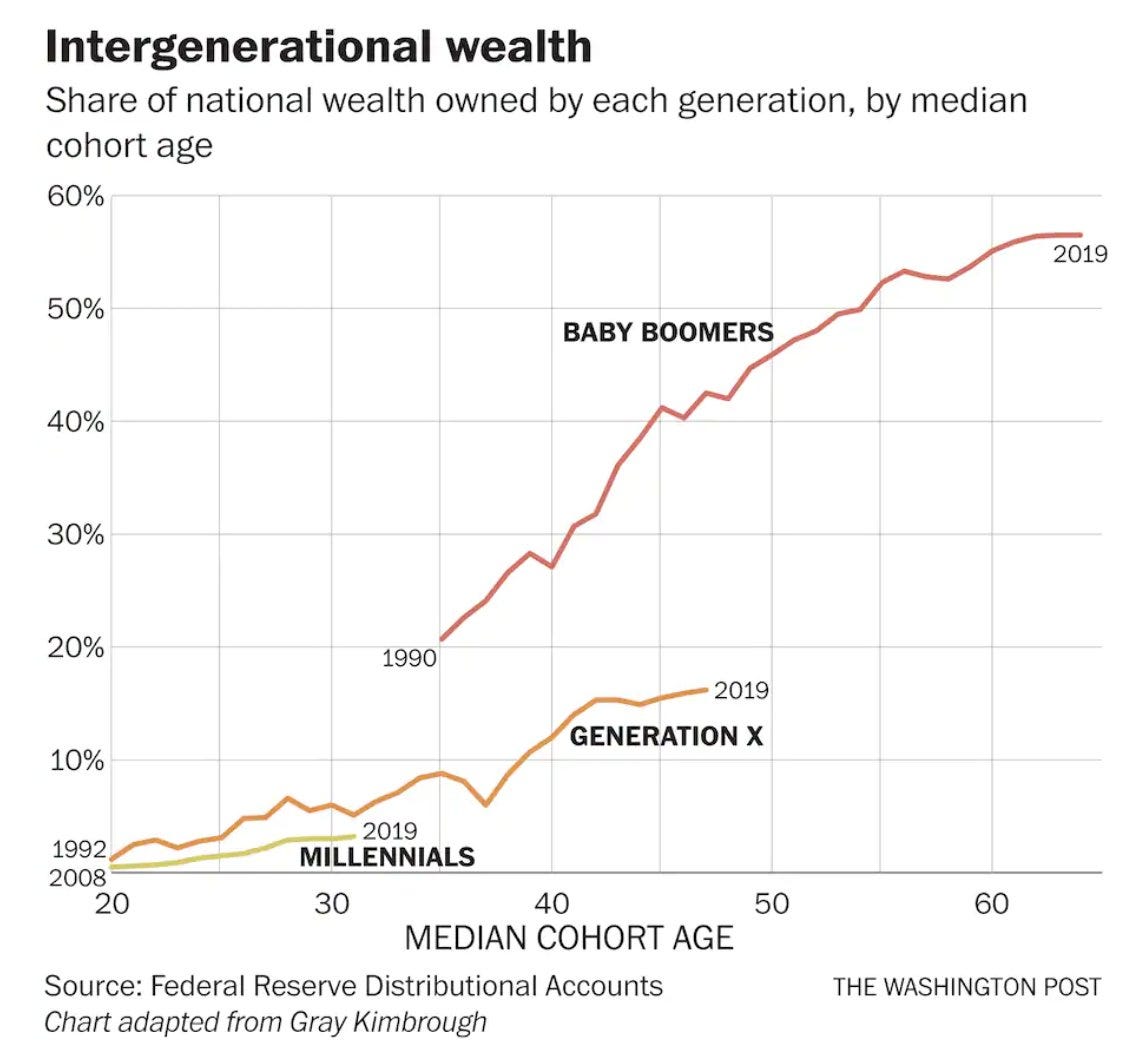

I came across this chart last week, which I think explains a lot of emergent worldviews:

But my favorite song from Inside is “That Funny Feeling, in which Burnham sings over a melancholy, stripped-down production about the mundanities of life and the inevitabilities of American consumerism:

Female Colonel Sanders, easy answers, civil war

The whole world at your fingertips, the ocean at your door

The live-action Lion King, the Pepsi Halftime Show

20,000 years of this, seven more to go

Carpool Karaoke, Steve Aoki, Logan Paul

A gift shop at the gun range, a mass shooting at the mall

What line better captures America than “A gift shop at the gun range, a mass shooting at the mall”? We’re all inundated with content to deliver us our dopamine hits. But at the same time, climate change wages on (“The whole world at your fingertips, the ocean at your door”) and many people have an uneasy feeling that we’re nearing the end (“20,000 years of this, seven more to go”).

Yet consumerism charges ahead. (Another line of the song is, “In honor of the revolution, it’s half off at The Gap.”) We don’t really know what to do, so we just continue on buying stuff and watching stuff.

This is the general sentiment shared by many Millennials and Gen Zs, people who have been crushed by student debt and depressed by climate change and made numb by partisan vitriol. When you look at charts like the one above on income distribution, or this chart of student loan debt, that sentiment doesn’t feel so shocking:

![Student Loan Debt Statistics [2022]: Average + Total Debt Student Loan Debt Statistics [2022]: Average + Total Debt](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!5OKQ!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fbacfd242-d5b3-4c2c-8894-48599f6c5857_800x576.png)

Of course, you can’t lump Millennials and Gen Zs into the same bucket. Millennials were told to follow their dreams and told that they could do anything, be anyone; they came of age with a sunny optimism. That optimism is now hardening into a cold nihilism, but Gen Zs were from the start more pragmatic, more pessimistic, more listless. (There’s a reason Gen Zs denote laughter with 💀 or ⚰️ .)

At the beginning of the pandemic, Ryan Brooks at Buzzfeed News wrote a great piece about how young people were faring. Some quotes from people in their teens and early 20s:

“I saw [my parents] take any and every job they could to keep us from going completely bankrupt [during the 2008 recession] and to keep our apartment and car—unfortunately, that didn’t work out.”

“Kids are intuitive; we know when something’s wrong. I saw my parents go into major debt, I saw them working 50 to 60 hours a week, and I never want to see them struggle like that again.”

“I’ve always felt like I’ve had to look over my shoulder to see what’s coming next, and it’s frustrating.”

Of course, anti-work, anti-establishment, and anti-capitalist sentiments are nothing new in young people. Banksy rose to fame in the 90s with art evoking the same feelings; younger artists and activists have been recoiling from “the system” for generations. But what’s unique about new generations is how aware of everything we are, thanks to the internet and mobile and social media.

Works by artists like Banksy could just as well be created by disillusioned Millennials and Gen Zs in 2022.

There’s a tension in America between corporations that are seeing record profits (well, until recently) and consumers, who are experiencing record inequality. I discovered the Brooklyn-based artist CJ Hendry last week, who makes incredible drawings using only colored pencils. I came across her colored pencil portrait of Mickey Mouse suffocating in plastic wrap, and was struck by how it seems a metaphor for American culture right now.

People—and especially young people—are hurting.

Technology is both an amplifier and a salve. People who came of age with smartphones clearly have a tenuous relationship with them. Take these comments from a TikTok video reminiscing on a time without phones:

They’re sad to read.

One of the things about Bo Burnham’s Inside that makes it so compelling is how it captures both the good things and the bad things about technology, while also understanding that technology’s presence in our lives is now inevitable.

It’s interesting to think about how new generational consumer behaviors translate into new businesses. We’re seeing a slew of startups building better solutions to the housing crisis, the climate crisis, the education crisis. I wrote about many of them in March’s The Glass-Half-Full View of Technology. But there are also less obvious impacts from consumer behavior:

We’re seeing the rise of more authentic social media—apps that focus more on the present, and less on curating a flawless online persona for future benefit. I first wrote about BeReal on June 2, 2021 after my Paris-based internet friend Marie Dolle sent me a Twitter DM about how BeReal was spreading like wildfire across Paris. Twelve months later, it’s taking American colleges by storm. (This viral TikTok on BeReal has 1.2M views.)

We’re also seeing a mental health renaissance in reaction to the Millennial and Gen Z mental health crisis. Companies like Headway, Real, and Pace are building better ways to access therapy and to find community.

And we’re seeing the emergence of more escapist forms of media, namely VR. Over the weekend, I went with my family to the Harry Potter VR exhibit in Madison Square Park. We flew on broomsticks over Hogwarts and fought Death Eaters. Every time I experience VR, I have full conviction that it will live up to its hype—just a bit later than we all expected. I think of a Tim Sweeney line: “I’ve never met a skeptic of VR who has tried it.” And as more people feel the hardships of the real world—income inequality, lack of homeownership, partisan politics—more people will want to escape to immersive and fantastic experiences.

Whether this is a good thing is up for debate—we should, of course, still fix things like income inequality and climate change. (And we need policy changes to complement private sector solutions.) But consumer technologies will always adapt to changes in the people they’re being built to serve—and with the Gen Z and Millennial generations radically different than their predecessors, this will mean some significant adaptations.

Check out clips from Bo Burnham: Inside on YouTube, like this one:

Related Digital Native Pieces

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: