What Gen Z Thinks About Work, College, and the Internet

Conversations with Five Gen Zs: Nepo Babies, Mental Health, & Capitalism

This is a weekly newsletter exploring the collision of technology and humanity. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

What Gen Z Thinks About Work, College, and the Internet

At the World Economic Forum’s meet-up in Davos earlier this month, two senior executives at McKinsey shared their latest research on Gen Z. Here’s an excerpt from Insider:

“Perhaps the defining characteristic of Gen Z is that, instead of wanting to revolutionize, Gen Z is comfortable with the idea of change through structure.” Francis, who is a senior partner at McKinsey’s office in São Paulo, Brazil [and the firm’s Chief Marketing Officer], told Insider. “The millennial generation was like ‘Let’s blow up all the institutions and start from scratch’,” she said, noting that Gen Z takes a more “pragmatic” approach.

Francis pointed out that Gen Z witnessed how “their parents suffered various crises around the world”—the eldest would have been 12-years-old during the 2009 recession.

“So it’s like, okay, yes, I want change. But I am prepared to work that through existing structures,” she adds.

Hmm 🤔 My view is that this is…completely wrong.

From what I’ve seen, Gen Z is distinctive in how much they do want to blow up the system. If anything, Millennials are the generation willing to “work within existing structures” to change things; Millennials are the ones you might describe as “pragmatic.” (One of my favorite Gen Z writers, Casey Lewis at After School, agrees that McKinsey is way off base.)

One potential nuance: Millennials were also angry, also unhappy with institutions. The difference: they had fewer alternatives. Now, as Gen Zs come of age, the internet has provided them with nearly infinite alternatives to earn a living. They no longer need corporate America in the way Millennials did; they no longer need to work a 9-to-5. They can be a YouTuber or a TikToker, a Twitch streamer or a Whatnot seller, a Roblox developer or a Discord community manager. There are more ways to design a life and a career.

I’ve explored Gen Z in depth before: last summer’s Minions and Gen Z Characteristics was one of my longer pieces, delving into 10 specific characteristics of the up-and-coming generation. In that piece I wrote, “When you account for the fact that Gen Z is now the largest generation in the U.S., small-scale behavior changes compound into macro-sized cultural shifts.”

This is why studying young people matters. Gen Z (roughly anyone born between 1997 and 2012) is two billion strong globally. In tech, we often talk about “platform shifts” and new technologies (blockchain! AI! cloud!), when new behaviors, attitudes, and worldviews just as often inform which companies break through. (To be fair, it’s usually a combination of the two.) If I think back 15 years, the Millennial coming-of-age powered companies ranging from Instagram to YouTube, Robinhood to Airbnb. The question is: what companies born today will ride the wave of Gen Z?

As an investor and consumer behavior enthusiast, I often find there’s a gap in life when it’s difficult to keep your pulse on a younger generation. This gap comes when you’re not so young anymore yourself (😪), but you don’t yet have kids to observe. The solution I’ve come up with is to regularly talk to Gen Zs—to act as an anthropologist of sorts, studying how they behave and interact and transact.

You learn a lot by doing so—and by supplementing with far too much time on TikTok and Reddit. One example learning from (gently) interrogating a 15-year-old cousin on Christmas: the coolest brands in her high school are logos familiar to any 30-something Millennial.

PacSun is huge again, particularly after the brand invested in an expansive Roblox world called PacWorld. Banana Republic is back after pivoting to high fashion. J Crew is experiencing a resurgence under creative director Olympia Gayot. And Abercrombie & Fitch has somehow weathered years of controversy (including a brutal Netflix documentary) to again become teens’ brand of choice.

This week’s piece centers around five quotes from recent conversations with Gen Zs.

I find each quote to embody broader trends in generational behavior, with trickle-down effects for how we communicate, how we shop, and how we construct our culture. Hopefully, each acts as a harbinger of large-scale societal shifts yet to come.

Quote #1: “I kind of wish phones didn’t exist.”

Gen Z is nostalgic. Studies have shown that nostalgia tends to rise during periods of stress and turmoil, and the events of the past few years have engineered something of a nostalgia bubble. A global pandemic, Trump and political polarization, the war in Ukraine, Brexit, a steadily-warming planet. It’s natural for people to long for the halcyon days of yesteryear.

Brands are taking advantage, of course. Coach built a vintage drive-in theater for its runway show last year; Old Spice, not to be outdone, launched a traditional barber shop harking back to the 1950s. You can’t blame them: #nostalgia has 66.1 billion views on TikTok.

And it’s not just Gen Zs: Millennials are also nostalgic, and the 90s are as much in vogue as the naughts. But my view is that Gen Z is nostalgic for a very specific reason: this is a generation that has never known a world pre-internet. The iPhone turned 15 last summer, meaning that today’s high schoolers don’t remember a time without it. As a result, this generation has mixed feelings about their tech-dependence.

This shows up in interesting ways. One fascinating phenomenon is the embrace of analog technologies. In 2021, vinyl outsold CDs for the first time in 35 years. Half of the people who bought vinyl don’t even own a record player! (Another impressive stat: last year, 1 of every 25 vinyl records sold in the U.S. was a Taylor Swift album.)

Young people have also embraced disposable cameras, wired headphones, and vintage game consoles. (I recently played Mario Kart on an old-school Nintendo 64 and I have to say, it was cathartic.) A BuzzFeed reporter wrote a piece this week titled, “I Tried A Flip Phone For A Week For My Mental Health And Here’s How It Went.”

A common refrain when I talk to Gen Zs or scroll the depths of TikTok is some version of “I wish phones didn’t exist” or “I hate my iPhone” or, saddest of all, “I didn’t know what insecurities were until I got my first phone.”

Social media has taken a toll on young people’s mental health, but it’s difficult to measure that toll. Meta’s internal studies, published by The Wall Street Journal last September, indicated that 1 in 3 teenage girls felt Instagram worsened their body image issues, though that data was correlational and self-reported. The American Psychological Association writes: “Studies have linked Instagram to depression, body image concerns, self-esteem issues, social anxiety, and other problems.”

A new study—released this week from the University of Amsterdam’s School of Communication Research—examined 210,000 Instagram DMs belonging to 100 adolescents in 8th and 9th grade, finding that expressions of happiness outnumbered expressions of sadness 4-to-1. (To me, this is more revealing about how people convey emotions to friends than about how social media affects mental health.)

It’s clear that younger people are experiencing a mental health crisis, likely in part because of their relationship with technology.

The good news is that Gen Z knows it has a mental health problem. Mental health isn’t stigmatized like it is in older generations; more and more people are seeking help.

Technology facilitates finding that help. Marketplaces like Headway connect you with a therapist and make sure your insurance covers it. Pace groups you with strangers and a trained facilitator to talk about difficult topics. Woebot is an AI chatbot that’s there for you whenever you need someone to talk to.

No category better underscores the duality of tech than mental health. Our digital world simultaneously inflames our mental well-being and offers more accessible, more affordable, better solutions.

Quote #2: “I met most of my best friends online.”

In 2006, Time Magazine unveiled its person of the year: You. Time set out to recognize the rise of user-generated content, as millions of people began to populate the web with content across YouTube, Myspace, Wikipedia, and so on.

The rise of UGC created a me-centric culture. All of a sudden, everyone had something to say. Twitter’s original prompt was “What are you doing?”, encouraging lots of people to share what they were eating for lunch. Talking about ourselves—loudly and publicly—became expected.

But while Millennials were trained to be individualistic, I’ve found that Gen Zs are much more focused on the collective. I wrote about this a few years ago in Digital Kinship, arguing that belonging was replacing status as the core human need online. Many young people don’t care about performing for others with airbrushed photos and curated grids; instead, they just want to be part of a community.

The solution for young people is finding community online. This has given rise to interesting phenomena: the act of watching people play video games; mukbangs, livestreams of a creator eating; even sleep streaming, the act of watching people sleep.

Of course, older people also crave belonging. The loneliness epidemic is affecting every generation. A recent study found that globally, one of every three people of all ages reported feeling lonely; a 2019 U.S. study found that three in four American adults felt lonely. Last week’s piece was about the dangers of obesity, but loneliness is far more deadly: ongoing loneliness raises a person’s odds of death by 26% in any given year.

Young people are uniquely vulnerable. The same factors that power nostalgia in that younger cohort—the pandemic, student loan debt, gun violence, climate change, the overturning of Roe v. Wade—also contribute to stress and loneliness, in turn creating the urge to form intimate connections. More and more often, those connections are happening online.

Quote #3: “I don’t have a dream job because I don’t dream of labor.”

This quote has become something of a Gen Z rallying cry. I see it and hear it often, and it perfectly captures a younger generation’s wry, borderline-nihilistic attitude.

It also captures broader trends—blowbacks against capitalism, against institutions, against work itself. We see flavors of this in the rise of the subreddit r/antiwork, now 2.4 million members strong (members call themselves “Idlers”), a 185x multiple on the 13,000 members in 2019. We see flavors in the much-hyped “quiet quitting” phenomenon of late 2022. We see flavors in the recent backlash to “nepo babies.”

Vulture had a long piece chronicling the history of nepo babies, but in short: a nepo baby is the child of a famous person (or persons) who is the beneficiary of nepotism. The phrase has its roots in this February 2022 tweet, whose author had just learned that Euphoria star Maude Apatow is a descendent of Hollywood royalty:

Millennials were understandably more distraught that a Gen Z had just referred to Judd Apatow, a mainstay of their formative years and the architect of everything from The 40-Year-Old Virgin to Superbad, as “a movie director.” 🤦🏼♂️

But the tweet launched a tidal wave. Internet sleuths learned that Stranger Things’s Maya Hawke was the daughter of Uma Thurman and Ethan Hawke. Emily In Paris’s Lily Collins turned out to be the daughter of Phil Collins (gasp). Even Cousin Greg from Succession wasn’t innocent! The actor was the son of one of the guys who designed the Rolling Stones’ lips logo.

The internet especially had a field day with a new film called The Rightway, directed by Steven Spielberg’s daughter, starring Sean Penn’s son, and written by Stephen King’s son. Oof.

What people were really mad about, of course, was that the system felt rigged. Nepo babies aren’t new (see: Jamie Lee Curtis, Jane Fonda, Gwyneth Paltrow), but the term offers a shiny new wrapper for a well-trodden phenomenon. The nepo baby backlash rhymes with past movements like Occupy Wall Street, GameStop mania, and the rises of both Trump and Bernie. People are sick and tired of a broken system.

We see this in Gen Z’s collective exhaustion with corporate America. To a new generation, Millennial protagonists like Anne Hathaway’s workaholic “girl boss” in The Devil Wears Prada are just…sad.

This becomes clear when you read enough TikTok comments:

Going back to my point earlier, Gen Zs now have more options. Entrepreneurship has never been easier, with companies like Stripe and AWS offering low-cost, low-friction building blocks. Many large internet platforms create thousands or even millions of digitally-native jobs. These platforms include stalwarts like YouTube and Amazon, but also newcomers like Metafy (gaming coach), Office Hours (expert network), and Leland (career coaching). While American capitalism remains broken, favoring the rich and well-connected, the internet and innovative tech startups provide some lubricant on economic mobility that didn’t exist in an analog world.

Quote #4: “Half my friends have no intention of going to college.”

This quote wasn’t much of a surprise to me; it fits the data. A January 2022 survey from the ECMC Group found that only 51% of Gen Zs want to pursue a four-year college, down from 71% just two years ago. Meanwhile, 56% believe that a skills-based education makes more sense in today’s world.

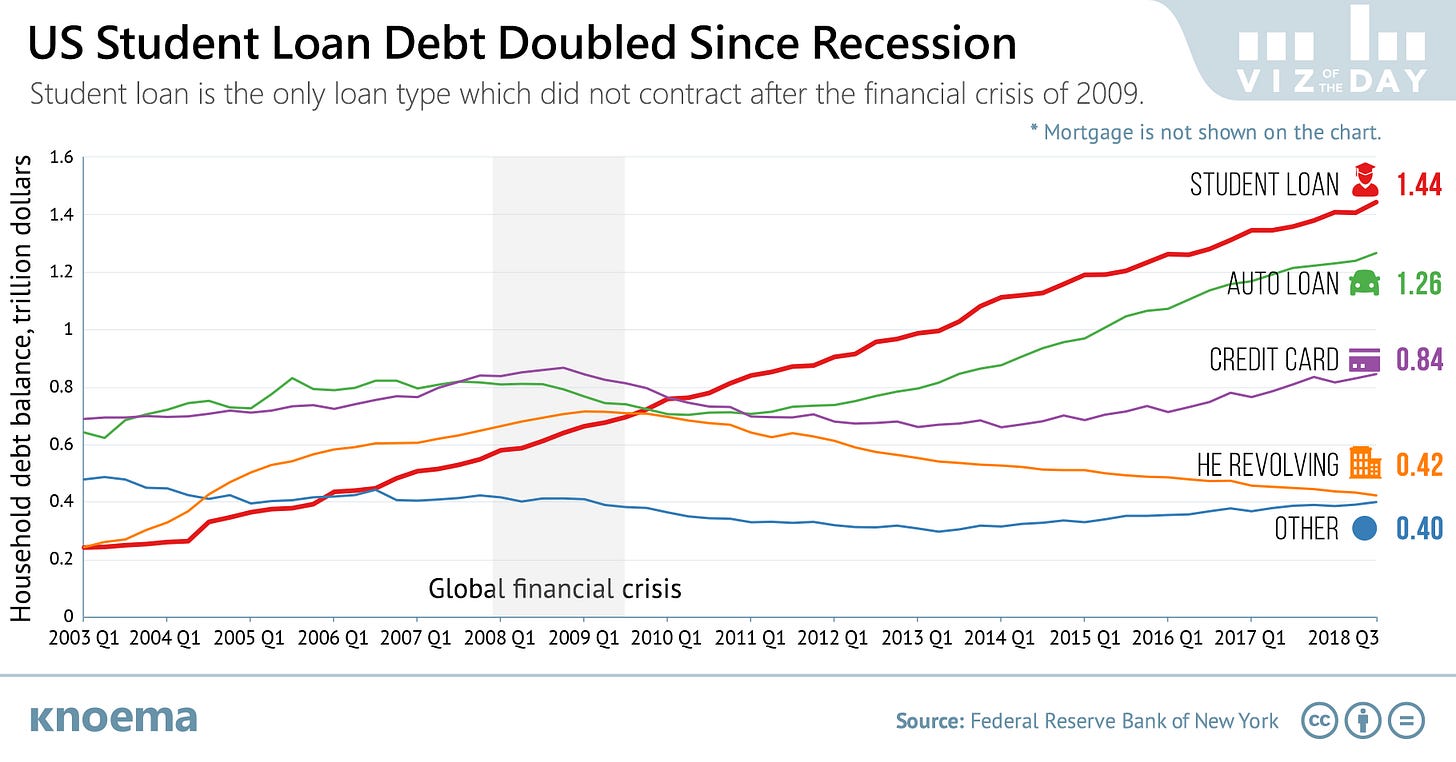

From fall 2019 to fall 2021, undergrad programs saw a 6.6% decline in total enrollment. This decline is somewhat COVID-related, but also speaks to longer-term trends: for many people, college is simply becoming untenable. Student loan debt has ballooned, growing 100% to ~$1.5 trillion from 2008 to 2018.

The cost of education is growing 8x faster than real wages. In the 1950s, 30% of household income was enough to pay for college. Today, people need to shell out 80% of their household income. Two-year colleges and vocational schools look like better options.

(This problem isn’t unique to education: since 1965, housing prices have swelled 118%, while wages have grown only 15%. This gets back to the last section on anti-capitalist sentiment.)

Education has been a slow sector to innovate, as startups run into the buzzsaws of government bureaucracy, thin budgets, and sluggish sales cycles. Regulated markets can be more difficult to reinvent. But education is an attractive market in its scale: it’s a $1.6 trillion market in the U.S. ($4.7 trillion globally) and the nation’s second-largest sector by employment, behind only healthcare.

In 2021, I wrote about the unbundling of college—how we’re seeing a cleaving of college into “learning” and “community.” Much of college has historically been about “the college experience”—the Animal House-esque rite of passage for adolescents. I’ve always liked how Ian Bogost once referred to America’s perception of higher education: “A safe cocoon that facilitates debauchery and self-discovery, out of which an adult emerges.”

Yet with college becoming prohibitively expensive, young people will need to seek both learning and community elsewhere.

Many startups facilitate new ways of learning. Outlier makes your typical “college education” more accessible, lowering costs by 80% with online courses from places like the University of Pittsburgh and offering full refunds to students who do the work but don’t pass. Guild, meanwhile, is an upskilling platform used by big corporations like Walmart and Taco Bell. (The piece from 2021 goes into more depth about companies in this category.)

New avenues for learning are especially in-demand when the labor market moves quickly: 85% of today’s college students will have jobs in just 11 years that don’t currently exist. The traditional undergrad education may wane, replaced by skills-based programs that are refreshed every few years with employer-funded workforce development training.

Meanwhile, forgoing the social development that college facilitates (and its built-in access to a community) means young people will have to turn elsewhere for belonging. The most likely place: the internet, and its FYPs and subreddits and Discord servers and group chats and MMOs and livestreams.

Quote #5: “I basically live online.”

One of my favorite examples of skeumorphism—the phenomenon of user interfaces designed to resemble real-world counterparts—is tabs in the browser resembling folders in a filing cabinet.

I was chatting recently with an entrepreneur building for Gen Z, and she said something interesting: “Gen Z’s brains are browsers with a million tabs open.” Her point was that Gen Zs are exposed to information overload, constantly flooded with peer pressure and comparison and FOMO. Overflowing filing cabinets. “Escapism,” the entrepreneur continued, “isn’t just for fun—it’s for survival.”

Digital natives have grown up in a unique world. As the YouTuber Thomas Flight puts it: “We live in a time when more interesting ideas, concepts, people, and places can fly by in the space of one 30-minute TikTok binge than our ancestors experienced in the entirety of their localized illiterate lives.”

This is full circle from “I wish phones didn’t exist.” Young people sometimes reject technology—and feel depressed and burdened by it—yet technology is also their refuge from reality. This will become even more the case as we march toward richer media formats: we’ve gone from text to photos and from photos to videos; next are 3D, immersive virtual worlds.

Gen Z is the lifeblood of the internet, fueling the web with UGC and becoming early-adopters of new tools. On average, a member of Gen Z spends 12 hours a day (!) interacting with online content. And we’re seeing young people become more and more adept at being online.

A new Gen Z buzzword is “rizz,” which effectively means “One’s ability to seduce a potential love interest.” Used in a sentence: “The ladies love him—he’s got rizz!” A new startup called Rizz has nothing to do with that definition, but is building a product as timely as the buzzword. Rizz lets you generate social media content or messaging content in seconds, using AI. The input “Generate a funny one-liner for my hinge match, she likes boba” produces the output “Hey there, care to grab some boba and see if we’re a matcha made in heaven?”

Young people have grown up in a world with mobile and cloud; now they’re becoming fluent in a world teeming in AI. One fact that makes you think: many Gen Alphas—the generation after Gen Z—won’t remember a world without ChatGPT. Tech burrows into our lives, and despite our love/hate relationship with it, we come to expect it and rely on it.

Final Thoughts

I’m always fascinated by how people contradict themselves. We often say one thing, but our actions say another. A few examples of Gen Z contradictions—

Preach sustainable living, yet shop at SHEIN

Eschew credit cards, yet embrace BNPL with open arms

Wish technology didn’t exist, yet rely on it for their most meaningful relationships and livelihoods

Contradictions are natural: we’re all multi-faceted, complex, flawed beings. The last one here is most fascinating to me. Technology is a double-edged sword.

In 2023, this piece wouldn’t be complete with a generative AI interpretation of Gen Z. Here’s the Midjourney output for “Gen Zs staring at their phones with mixed emotions.”

Three years ago, I named this newsletter “Digital Native” because the idea of people growing up in a tech-centric world fascinated me. Our brains haven’t evolved in millennia, yet our world has transformed in a handful of years. The pace of that transformation is only accelerating.

Studying how young people are coping with this change helps us understand what will happen when they grow up into our politicians, our business leaders, our highest-spending consumers. Quotes like those in this piece reveal a window into what the future might hold. (I’d love to hear from any young people about what I got wrong, or other observations and anecdotes that may shed a light on new behaviors.)

Behavior shifts influence capitalism and commerce and culture. We can do our best to examine these shifts and predict their ripple effects, but ultimately we’ll have to just wait and find out.

Sources & Additional Reading

Three of my favorite Gen Z newsletters are After School, High Tea, and The Future Party

Related Digital Native Pieces

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: