What People Misunderstand About The Creator Economy

How The Creator Economy Unlocks Self-Expression, Diverse Voices, & Economic Mobility

This is a weekly newsletter about how people and technology intersect. To receive this newsletter in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

What People Misunderstand About The Creator Economy

Over the weekend, I tweeted out a survey showing that “YouTuber” is the career today’s kids aspire to above all others. Being an online creator is 2x as popular as being a pop star or movie star, and 3x as popular as being a professional athlete or astronaut.

The survey is actually a few years old—I expect that the pandemic, the rise of TikTok, and the growing ubiquity of internet culture have all made being a creator more desirable to more kids.

My tweet inspired a lot of handwringing, with many people forecasting society’s imminent demise. I was surprised by the backlash to the survey results, though maybe I shouldn’t have been: there’s a long history of attacks on new forms of creative expression. In the 1940s, people criticized Hollywood’s assembly-line approach to filmmaking. In the 1960s, people feared television was rotting our brains. In the 1980s, (mostly white) people fretted over rap lyrics and the rise of hip-hop. Demonizing art and those who create it is an age-old tradition.

I spent the past few days thinking about what people were missing and why the rise of online creators is an important and positive societal shift. I boiled it down to five reasons:

This movement is about creative expression.

It’s a horizontal trend, not a vertical trend.

It enables and empowers more diverse voices and stories.

It lets workers reclaim their agency.

It breaks down outdated power structures.

1) Creative Expression

In a 2005 interview with WIRED magazine, Barry Diller weighed in on the future of media:

“There is not that much talent in the world. There are very few people in very few closets in very few rooms that are really talented and can’t get out.

People with talent and expertise at making entertainment products are not going to be displaced by 1,800 people coming up with their videos that they think are going to have an appeal.”

This isn’t to pick on Diller, who had an illustrious career as the CEO of both Paramount and 20th Century Fox and as the founder of IAC. But you’d be hard-pressed to find a statement that proved more wrong. The same year that Diller gave that interview, YouTube was founded; Instagram, Twitter, and TikTok soon followed. It turned out that there was a lot of talent in the world—many people in many closets in many rooms. The internet just needed to unlock it.

One misconception about creators is that they’re just seeking fame and fortune. The same survey of today’s youth showed that “Creativity” is the top-rated reason for wanting to work as a creator, outpacing celebrity and money. Being a creator is a form of self-expression.

Here are the top 5 reasons that kids give:

Creativity (24%)

Fame (11.4%)

Self-expression (11%)

Money (9.8%)

Connecting with people and finding community (8.4%)

As more kids become creators, more creativity is unleashed. While YouTube initially broke down barriers to creating content, creation is becoming even easier over time.

TikTok takes it a step further: it removes friction to create not only with its no-code in-app tools, but with remix culture. Features like “Duet” and “Stitch” and the ability to use other peoples’ sounds dissolve the cold start problem, letting you build on other creations. Every piece of content is a building block for a new one. You not only have have the tools to make content, but you have inspiration about what content to make.

Newer social apps continue to make creation easier. Piñata Farms, one of our investments at Index, lets anyone make fairly complex memes in just a few seconds. Clubhouse lets you be a creator just by talking. The barriers to producing content are lowering, both through creation tools and through a culture that encourages creation. This unlocks more talent and creative expression.

2) Horizontal, Not Vertical

A common response to my tweet was “But we need doctors and engineers and teachers!” The thought was that if kids were growing up to be YouTubers, society would find itself with a terrible shortage of people in “regular”, very important jobs.

This makes the common mistake of lumping creators with Hollywood-types. Yes, many creators are comedians and actors and entertainers. But the creator economy is a horizontal trend, not a vertical one: it’s much broader than Hollywood.

You can be a doctor and a YouTuber. You can be an engineer and a YouTuber. The careers aren’t mutually exclusive. Being a creator means making content for other people and (typically) earning income off of that content and off of that community.

Some of the most popular YouTubers fit different molds:

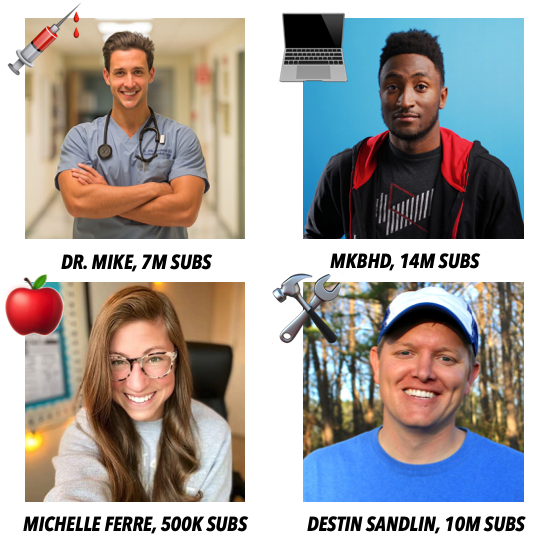

Dr. Mike is a family physician who offers health tips to his 7 million subscribers. Marques Brownlee, better known as MKBHD, reviews tech products. Michelle Ferre is a primary school teacher who also runs a YouTube channel called Pocketful of Primary, and Destin Sandlin is an engineer behind the STEM videos on SmarterEveryDay.

These creators are a far cry from Hollywood types. But with internet platforms, they can broadcast their knowledge and expertise. They’re also able to better monetize what they know and what they love: before YouTube, MKBHD might have worked as a techie at the Apple Store; now, he employs a dozen people and does tech reviews for 14 million subscribers. In the future, doctors and engineers and teachers can have an additional income stream. There will be a long tail of creators who still fulfill other roles in society.

I’ve also argued that the creator economy isn’t limited to consumer—it’s an enterprise trend as well. Companies like Figma and Notion, both in our portfolio at Index, or like Airtable, where I used to work, let everyday people build with software. Each has a vibrant community of creators. They become creator economy companies—and become more than just tools—when they layer on a marketplace to let creators sell what they build. Airtable Marketplace, for instance, lets you build an Airtable App and then earn income as others use your App. A mom-and-pop shop owner who builds an App to track her inventory can make money when other shop owners use what she built.

The creator economy is broader than entertainment and it’s broader than consumer—it’s about people being able to use technology to build in new ways, and then being able to use the internet as distribution to share and monetize those creations.

3) Diverse Voices

In 1940, Hattie McDaniel became the first Black person to win an Oscar. McDaniel—the daughter of two former slaves—won for her portrayal of Mammy, the head slave at the plantation Tara in Gone with the Wind.

But when McDaniel won, she wasn’t sitting at the Gone with the Wind table with the main cast, including Clark Gable and Vivien Leigh. Instead, she was sitting at a small table tucked against a back wall. The hotel hosting the Oscars ceremony was a “no-Blacks” hotel and it had taken significant effort to even get McDaniel allowed into the building.

For the rest of McDaniel’s career, she was typecast by white Hollywood. She played a stunning 74 roles as a maid (she was famous for saying, “I’d rather play a maid than be a maid.”) And it took 51 years for another Black woman—Whoopi Goldberg—to win an Oscar.

Hollywood has long had a fraught relationship with race. But while traditional media has been slow to reflect the world we live in, the internet has opened the floodgates for diverse talent and stories. By removing the mostly-white, mostly-male gatekeepers of media, the internet ensured that anyone could create content for audiences around the world.

Platforms are taking efforts to invest in and amplify Black stories. YouTube recently launched #YouTubeBlack. Last month, TikTok tapped 100 Black creators for its incubator.

There’s still racism and bias across media. Last summer, TikTok was criticized for its treatment of Black creators, issuing an apology, and many Black creators aren’t happy with the app’s progress since. Black people are often the arbiters of mainstream culture, and their influence is still broadly unacknowledged and undervalued. Creators of color face an uphill battle compared to their white counterparts.

But the world of online creators is vastly more diverse and inclusive than mainstream media. While Hollywood has changed depressingly little since Hattie McDaniel won her Oscar 80 years ago (see: #OscarsSoWhite), the internet has reinvented creativity and art. Anyone can broadcast their story and find an audience.

4) Reclaiming Agency

Last week, I wrote about how we’re seeing “reclaiming agency” as a recurring theme in the GameStop and r/WallStreetBets phenomenon, in NFT mania, in the deification of Elon Musk. The young people coming of age today grew up during the Great Recession. They watched their parents struggle through the financial crisis, and they have an inherent skepticism of institutions and “traditional” career paths. They want to dictate their own fortunes.

The creator economy embodies this behavior shift. The internet levels the playing field, and anyone can use their hustle and savvy to amass a following and monetize that following. In a time when American capitalism is broken and when the rich get richer, the internet actually resembles something like a meritocracy.

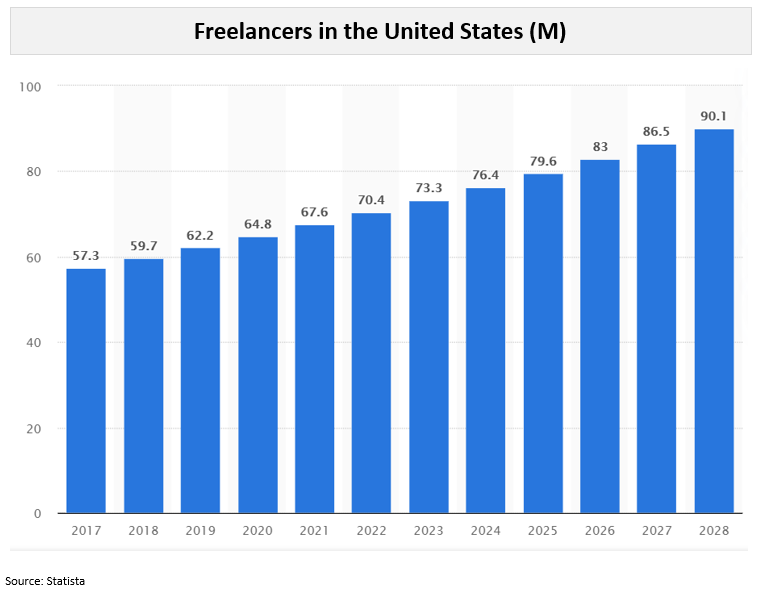

We’re just at the beginning of this shift—work will continue to disaggregate and the next generation of entrepreneurs will be “solopreneurs”.

There’s a robust ecosystem of software tools and platforms enabling this shift. You can manage your community in Circle and connect with members directly using ConvertKit. You can write on Substack, teach a course on Outschool, and sell art on Foundation. You can earn more income with Streamloots and run your business through Kajabi.

My friend Hugo’s market map is the best I’ve seen:

This economy will continue to grow, as all of the tools that support today’s businesses emerge to support tomorrow’s creators.

5) Removing Gatekeepers

This final point ties together the others. Each of the above is about removing the brokers and intermediaries of outdated power structures, and this is the foundation of the creator economy. NFTs and social tokens are the next iterations, which I wrote about in The Digital Renaissance earlier this month.

I think Chris Paik captures this point best. In his piece The American Dream Is Going Digital, he argues that the internet is the new land of opportunity:

“For my parents’ generation, the American Dream meant physically moving to America to pursue economic and social mobility—a better life. For today’s generation, the internet has replaced The United States as the Land of Opportunity—the place where hard work and an appetite for risk is rewarded the most.”

Final Thoughts: Imperfect Progress

Perhaps the most salient response to criticism of the “dream job” survey is that not all kids will be YouTubers. Most won’t succeed and will move on to other careers.

That’s because being a creator is hard work and often unforgiving. One study found that reaching the top 3.5% of YouTube channels—which means about 1 million views each month—only gets you $12,000 to $16,000 a year. That’s right around the federal poverty line. About 97% of YouTube creators aren’t making minimum wage from YouTube. One popular YouTuber, Shelby Church, wrote a blog post about how getting 3,907,000 views on a video only made her $1,276.

This is an imperfect and still-evolving economy. The big platforms have too much power and vacuum up too much of the economic value created. Even though many creators stitch together earnings across YouTube, TikTok, Patreon, Instagram, and so on, most are over-indexed on a single platform. They’re a YouTuber or a TikToker or an Instagrammer. I thought of this fact again last week when I saw this cringeworthy advertisement for a YouTubers vs. TikTokers boxing match 😐

Your platform determines their fate. One creator, for instance, saw his earnings drop 80% because of a change to the YouTube algorithm.

The ecosystem will improve as business models shift away from advertising and become more creator-friendly. Imagine taking a paid vacation or a sick day as a creator; platforms can do a lot to lower the pressure to create that takes a toll on mental health. Incomes are already more predictable thanks to platforms like Patreon, Substack, and OnlyFans.

There also needs to be a new infrastructure undergirding this new economy. Creative Juice will be part of the solution (and I’ll write more about the company in the coming weeks). But we’ll also need a full suite of tools for internet entrepreneurs—the same robust set of tools that have helped small businesses and large enterprises over the last 100 years. Creators are the new businesses, and these jobs are the jobs of the future.

Despite negative perceptions, the creator economy is a significant and positive shift in how we work, learn, and express ourselves. I’m hopeful that it will break down some of the calcified, outdated parts of American capitalism and reorient the economy to equal opportunity and economic mobility.

Sources & Additional Reading

YouTube and Patreon Still Aren’t Paying the Rent for Most Creatives | Herbert Lui, Marker

The Creative Apocalypse That Wasn’t | Steven Johnson, NYT Magazine

The American Dream Is Going Digital | Chris Paik

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive this newsletter in your inbox each week: