What Taylor Swift Can Teach Us About Business

From Viral Marketing to Market Sizing to Product Roadmaps

Weekly writing exploring how technology and humanity collide. If you haven’t subscribed, join 40,000 weekly readers by subscribing here:

Hey Everyone 👋 ,

This past week has been exhausting for many in the tech world. Though the startup ecosystem (and broader economy) avoided the worst case scenario, it came at the cost of many sleepless nights and frayed nerves.

As a result, I wanted to make this week’s piece somewhat more light-hearted, an escape from the somberness. Though the headline may sound trivial, there are interesting and important lessons here for all companies.

Let’s dive in.

What Taylor Swift Can Teach Us About Business

It’s no secret that I’m a massive Taylor Swift fan. Why? Billy Joel said it best when he called her “The Beatles of her generation.” Swift is a skilled songwriter and the only woman to win the Grammy for Album of the Year three separate times (a feat she accomplished at the age of 31).

But Taylor Swift is also a fascinating business case study. She’s one of the savviest businesswomen of her generation, and she’s unique in how deftly she’s leveraged the internet from the very beginning. I’ve wanted to write a piece about what we can learn from Swift for a while. With her Eras tour kicking off tomorrow, this is as good a time as any. Ben and David at Acquired had a terrific (and long) podcast episode about Swift a little over a year ago, but other than that I haven’t seen many breakdowns. My hope is that this piece both 1) sheds light on one of the first digitally-native superstars, and 2) extrapolates relevant lessons for startups.

This piece is also an excuse to delve into topics that interest me: viral marketing, product roadmaps, market sizing. I’ll use Swift as a launching-off point for various startup concepts. How does Taylor Swift relate to Figma and Notion, Red Bull and Apple, Datadog and Square? We’ll find out.

First, for those who aren’t Taylor fans (🚩), a word about why you should care:

With her Eras tour, Swift is set to the become the highest-grossing female touring artist of all time. She holds the record for most songs to ever chart on the Billboard Hot 100 (188 songs), and last fall became the first artist to own the entire Top 10 simultaneously. In 2019, the American Music Association named her the Artist of the Decade for the 2010s, and Billboard recently named her #8 on its Greatest Artists of All-Time list, highest among contemporary artists and sandwiched between Michael Jackson and Stevie Wonder. She’s still just 33.

One example of Swift’s influence:

When Apple went to launch Apple Music, it announced that everyone would get a three-month free trial. The problem: artists wouldn’t be paid during those three months. Swift, long a champion of artist rights, penned an open letter to Apple: “We don’t ask you for free iPhones. Please don’t ask us to provide you with our music for no compensation.”

Within 24 hours, Apple relented and decided to eat the cost itself. Eddy Cue openly apologized to Swift and other artists. It was a stunning backtrack for a company not exactly known for changing its stances (Exhibit A: Tim Sweeney). The point is: even if Swift’s music isn’t your cup of tea, you can respect her business acumen.

This piece will focus on five business lessons, each built around Swift’s career:

Great Products Expand the Market

It’s All About Community

Brand Building: Is Brand a Moat?

Product Velocity Wins

Reward Your Superfans

1) Great Products Expand the Market

Taylor Swift was born in Pennsylvania, but at age 13 convinced her parents to move the family to Nashville. Determined to be a country singer, Swift went door-to-door in Nashville to the major country music labels—which all rejected her. Undeterred, 13-year-old Swift began to write her own music and perform that music in bars around Nashville, hoping to be discovered.

The mechanics of the music industry are fairly similar to those of the venture capital industry. Music labels have A&R reps (A&R stands for Artists and Repertoire) whose job is talent scouting—they’re out and about looking for the next big thing. Once a label signs an artist, it offers an advance—essentially money to fund the production of an album—and the label then contractually owns the rights to recoup that advance and eventually profit. The industry is much more complicated than that, but that’s the gist. Like venture, music operates by a power law in which most artists fail, but the ones who make it (like Swift) more than make up for the ones who don’t.

In Nashville, RCA Records discovered a young Taylor Swift. But there was one problem: they didn’t want her to be a country singer-songwriter. RCA looked at the data, and they saw country music on the decline with young listeners; they looked at Swift, and they saw a teenager they thought they could mold for a more lucrative segment of the market. They could give Swift other people’s songs to sing, and she could be a vessel for the label.

They were wrong, of course.

Swift rejected RCA’s offer, unheard of for an up-and-coming artist. Swift later reflected, “I didn’t just want to be another girl singer. I wanted there to be something that set me apart and I knew that had to be my writing. Basically, there are two types of people. People who see me as an artist and judge me by my music. The other people judge me by a number, my age, which means nothing. It’s not really a popular thing to do in Nashville to walk away from a major record deal, but that’s what I did.”

Swift later signed with Big Machine Records, and the rest is history. (Swift’s catalog constitutes about 80% of Big Machine’s revenue.)

The key insight here is that RCA underestimated the market. Yes, country listenership was declining among young people. But great products revitalize stale markets and ultimately expand their markets. Swift did both, first proving that there was an opportunity in country music, and later growing beyond country to become a bona fide pop star.

Swift’s story reminds me of a fatal error in startups: underestimating market size.

A classic example is that of Uber. As Bill Gurley outlines in a great post from 2014, many experts dramatically underestimated Uber’s market opportunity. One finance professor at NYU, Aswath Damodaran, wrote: “For my base case valuation, I’m going to assume that the primary market Uber is targeting is the global taxi and car-service market.” He arrived at a TAM (Total Addressable Market) of $100 billion.

Damodaran’s error, of course, was not recognizing that a great product can expand a market. Uber offered a 10x better offering than taxis: coverage density was higher, which drove down average wait times to under five minutes; geolocation on mobile devices enabled anyone to call a car, nearly from anywhere; payment was done via mobile, meaning customers didn’t need to carry cash; the dual rating system ensured quality; and a digital record of each ride meant that Ubers were safer than cabs.

In New York, the taxi capital of America, ride-hailing apps quickly overtook traditional cabs, revealing that a 10x better product would crowd in more riders.

As Gurley puts it: “The past can be a poor guide for the future if the future offering is materially different than the past.”

Gurley also points to a similar mistake made by McKinsey, forty years ago:

“In 1980, McKinsey & Company was commissioned by AT&T (whose Bell Labs had invented cellular telephony) to forecast cell phone penetration in the U.S. by 2000. The consultant’s prediction, 900,000 subscribers, was less than 1% of the actual figure, 109 million. Based on this legendary mistake, AT&T decided there was not much future to these toys. A decade later, to rejoin the cellular market, AT&T had to acquire McCaw Cellular for $12.6 billion. By 2011, the number of subscribers worldwide had surpassed 5 billion and cellular communication had become an unprecedented technological revolution.”

Great products expand markets. Airbnb popularized home-sharing. Tesla brought electric vehicles mainstream. Red Bull effectively created the energy drink market, which now comprises $53B globally and is expected to grow 7.2% a year through 2027. (For its troubles, Red Bull owns 43% of the market.)

Taylor Swift is a classic story of a great product expanding a market. That same story has played out time and time again in the technology world. From the venture perspective, not investing in a company based on market size (particularly at Seed and Series A) can be a grave mistake.

2) It’s All About Community

One consequence of the digital age is that it’s become possible to cultivate global, vibrant online communities. For businesses, this manifests as communicating with customers and users; for artists, this manifests as talking to fans.

In her first decade of stardom, Taylor Swift was a Tumblr die-hard: she logged a stunning 27,000 (!) interactions with fans on Tumblr.

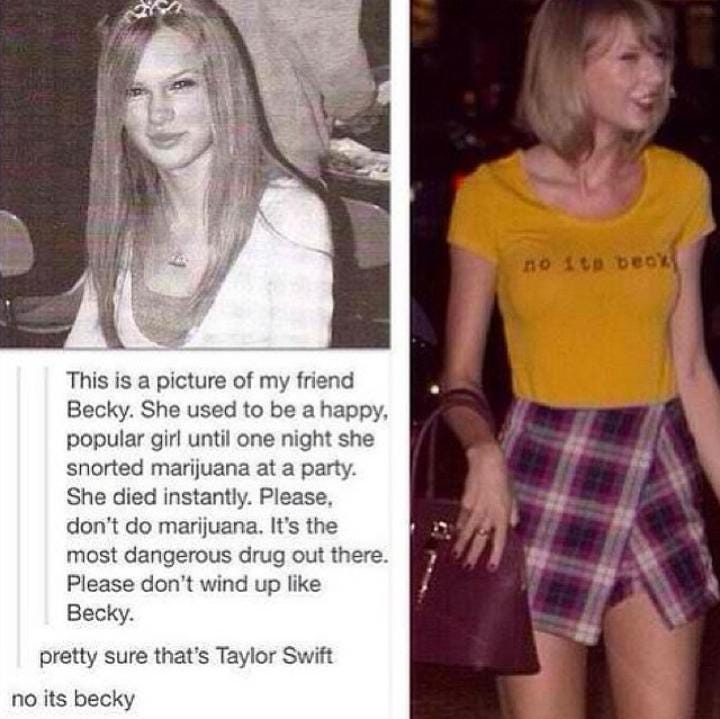

From ~2006 to ~2016, Swift was frequently liking, commenting, and reblogging fan content. Fans felt like she was one of them. Swift even formed inside jokes with fans. Most famous is 2014’s “no, it’s becky”—essentially, a Tumblr user told a story about a girl named Becky (below) who suspiciously looked a lot like a young Taylor Swift. Swift was later spotted wearing a “no, it’s becky” shirt, proving to be in on the joke.

More recently, Swift has updated her playbook for the 2020s, frequently commenting on fans’ TikToks:

Better than arguably any other artist, Swift meets fans where they are: the internet. Early on, she understood the power of nurturing and growing a loyal online community.

“Community” has now become something of a buzzword in the startup world. The best startups know how to cultivate their communities.

Last week, Figma launched its revamped Figma Community, a digital marketplace for users to post widgets, plug-ins, and other files. As Figma puts it: “Explore thousands of free and paid templates, plugins, and UI kits to kickstart your next big idea.”

Notion, another company we work with at Index, is equally brilliant at community management. One of Notion’s masterstrokes as it grew was tapping local “community ambassadors” in different cities around the world. Ambassadors organize offline and offline events, produce courses and tutorials, and share translations. Two ambassadors even run Notion’s 270K-members-strong subreddit.

Notion was always intentional about community, with Camille Ricketts (Head of Brand and Communications) and Ben Lang (Head of Community) leading the charge. At first, community was seen as a top-of-funnel channel to build brand awareness. But soon, Camille and Ben learned that community could drive activation, and even contribute to upgrade and expansion.

More companies are formalizing community management.

Common Room, which we’ve also partnered with at Index, is infrastructure for community management—an “intelligent community growth platform.” Linda Lian, Common Room’s co-founder and CEO, experienced the problem firsthand while working at Amazon Web Services: she spent her days managing a crowded Slack channel of AWS developers and logging members in a Google Sheet. It was a nightmare. Lian left to build Common Room to solve her problems.

There are dozens of disparate places that developers, customers, and users interact—Slack, Discord, Twitter, GitHub, Reddit, LinkedIn. Common Room’s goal is to tether everything together into one unified dashboard, offering a snapshot of community health and engagement.

“Community” is a vague and amorphous word, but it’s an essential concept for businesses to grasp. The best companies have millions of builders and users scattered across dozens of countries—this applies to API companies like Twilio and Stripe, to open source companies like GitHub and Confluent, to application software like Airtable and Asana.

Companies can learn from Swift: stay plugged in to your community. Talk to people. In a digital world, that’s easier than ever.

3) Brand Building: Is Brand a Moat?

There’s a frequent debate in the business world: is brand a moat?

In other words, can a company’s competitive differentiation come from its brand? My view has always been yes. There are better moats than brand, sure, but brand matters. Many iconic consumer companies will always enjoy an advantage because of the strength of their brands—and that advantage compounds, with the strongest brands enjoying name recognition that drives strong cash flows, which can then be plowed back into further growing the brand.

Let me digress from Swift for a minute and geek out about brands.

Marketing, in its modern form, essentially didn’t exist before the Industrial Revolution. There was such little product differentiation that it wasn’t necessary. Then manufacturing exploded, and production became cheaper and faster than ever before. New entrants crowded into the market, and marketing became essential. Today, marketing is often all that distinguishes a product.

Marketing rules our consumerist society. Children as young as two can recognize brands on shelves, and by age 10 children have recognition of 300 to 400 brands. The power of brand is clear. To use examples from three of the world’s strongest brands:

People buy Nike because they want to be like LeBron and Tiger and Serena.

People will watch a Disney movie because they know they can expect a great story.

People buy Apple products because Apple stands for innovation.

Apple offers an interesting jumping-off point, as for forty years Apple has consistently been at the top of the marketing game. In 1984, Apple commissioned the ad agency Chiat/Day to create its now-iconic Macintosh Super Bowl commercial. (Ridley Scott, the director of Alien, Blade Runner, and Gladiator, directed the commercial.) The message was clear: Apple is pioneering the future.

Chiat/Day went on to also produce Apple’s 1997 to 2002 “Think Different” campaign.

Many of the best brands play on how they make you feel. Apple evokes feelings of excitement and innovation. Nike evokes grit and passion and inspiration.

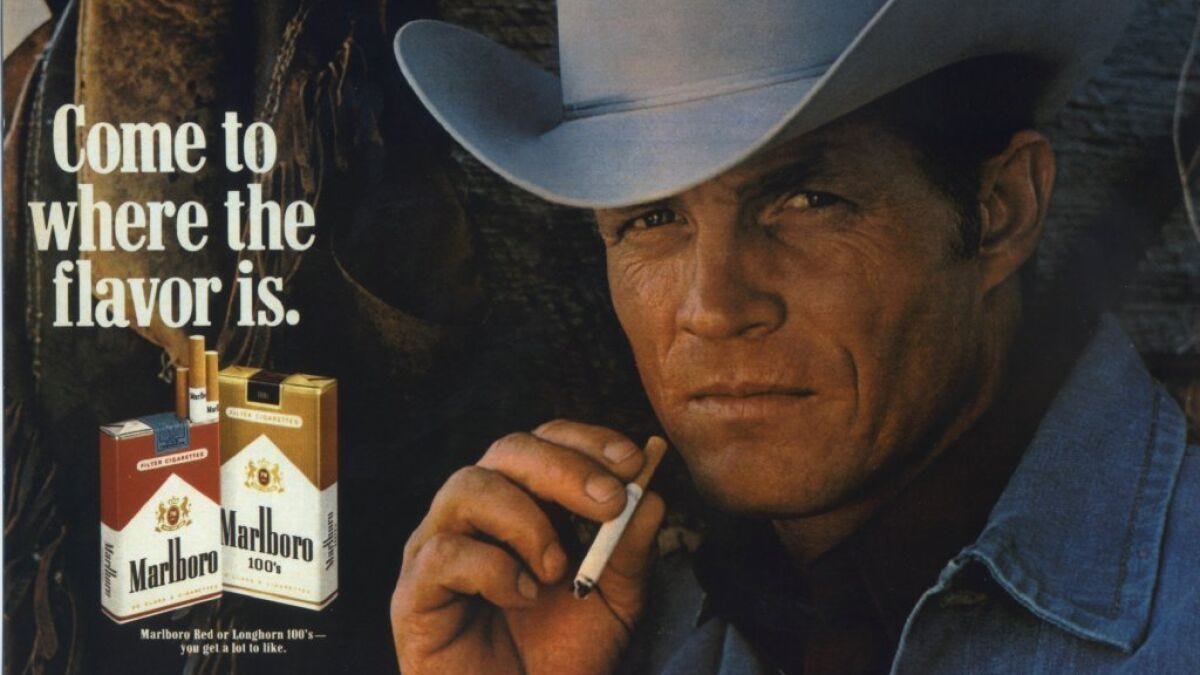

One of my favorite branding examples (but not one of my favorite companies!) is Marlboro. In the 1950s, Marlboro had a problem: it was a major producer of filtered cigarettes, but filtered cigarettes were considered feminine. So Marlboro came up with The Marlboro Man, an ad campaign portraying Marlboro tobacco products as rugged and masculine, often featuring cowboys. The campaign, which ran from 1954 to 1999, told consumers: if you want to be like The Marlboro Man, buy Marlboro.

Brands need distinct voices. Taylor Swift has one of the most clearly-delineated brands in pop culture. She embodies authenticity and vulnerability through her songwriting. She’s a role-model and a champion for artists. She stands by her values (donating proceeds of her songs to LGBTQ+ organizations, for instance, or speaking out against Republicans in Tennessee), just as the best brands stand by their values (Nike’s Colin Kaepernick ads come to mind).

Throughout her eras, she’s refreshed her brand to stay modern and in step with culture.

The best brands also evolve to stay modern (and yes, Apple’s first logo was an image of Isaac Newton sitting under the tree):

In a world of abundant consumer choice, brand is one of the most powerful moats to build. Just as people buy Nike or Apple or Disney because of the strength of those brands, people buy Taylor Swift products for the same association. (Chances are, you’ll listen to a new Taylor Swift album just because it’s a Taylor Swift album.) Swift’s brand gives her a head start, which powers a flywheel of ever-greater brand recognition and brand affinity.

4) Product Velocity Wins

One thing I admire about Taylor Swift is her sheer output. She’s prolific.

During COVID lockdowns, Swift recorded the album folklore, which she dropped without warning in July and which went on to win Album of the Year. A few months after folklore, she again dropped a surprise album—evermore.

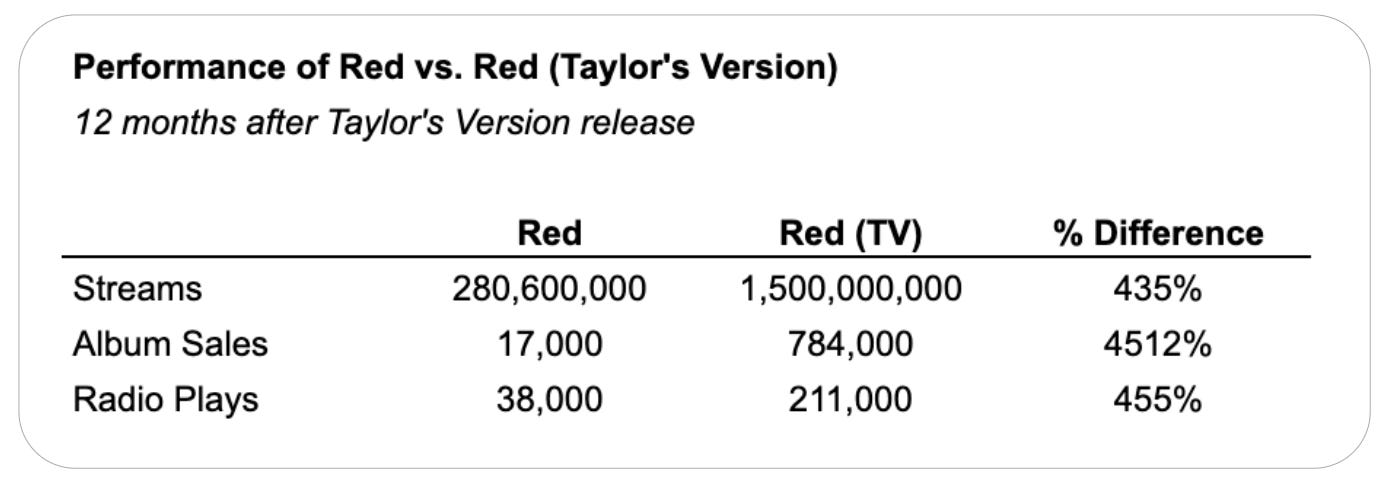

In 2021, Swift released two re-recordings of her past albums after losing the rights to her work when her previous label was sold. She brilliantly branded them Fearless: Taylor’s Version and Red: Taylor’s Version, thereby nullifying the value of the non-Taylor’s Version records. The strategy worked:

Both re-recorded albums included expanded “From the Vault” tracks of previously-unreleased material. Red (TV) came in at a whopping 30 songs, including the 10-minute version of “All Too Well”, which became the longest song to ever top the Billboard Hot 100.

Take this stat: over the 11 years from 2006 to 2017, Swift put out six albums with 82 total songs (7.5 songs / year). Over the four years from 2019 to 2022, Swift put out six albums with 125 songs (32 songs / year). Yes, two of those six albums are re-recordings, but Swift’s output is accelerating.

And that prolific output is tied to business metrics:

For Midnights, Swift revealed that if fans bought all four versions of her vinyl, they could align the covers to form a clock. (Gasp!) This was a thinly-veiled, but highly-effective effort to get fans to buy four times as much vinyl.

When Swift was close to claiming the entire top 10 of the Billboard charts, nearing the end of the charting week, her song “Bejeweled” was lagging. What did she do? She released a music video for the song, which propelled it up the charts and delivered her a clean sweep of the top 10.

When I think of Swift’s ever-growing output of work, I think of the product velocity of the best startups. Very few startups begin with a diverse set of products—Rippling and Wiz are two exceptions that come to mind. Most instead start narrow, and then layer on products over time to drive up average contract values and power strong net dollar retention.

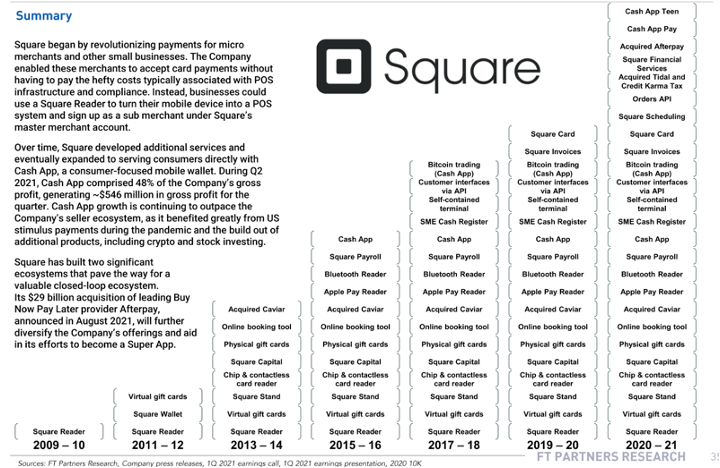

The product roadmaps for the best technology companies look like ever-increasing stepladders. Here’s one for Square, tracking its history from its Reader product through the additions of everything from Cash App to Square Payroll to Caviar.

Here’s a look at a similar chart for Datadog, which has been exceptional at layering on more and more products over the years.

Taylor Swift started narrow (country), then went broad (pop). She’s reinvented herself again and again, launching new “products” in each era of her career at an ever-increasing rate of acceleration.

The best startups follow that same playbook, mastering one segment with a best-in-class product and then layering on more and more bricks to capture market share and fortify their moats.

5) Reward Your Superfans

An artist’s superfans are her lifeblood: they’re the people who buy every vinyl, the people who rack up streams, the people who get the most expensive tickets on tour.

A company’s superfans are its lifeblood: they’re the customers with the highest spend, the strongest usage, the best retention.

Swift has always been someone to reward her superfans. While casual fans might get a reblog on Tumblr or a comment on TikTok, the most enthusiastic fans get something better: an invitation to Secret Sessions. Secret Sessions are small and intimate gatherings in Swift’s own home, in which she previews her new albums for a handful of fans (who have signed strict NDAs, of course).

Swift has other products for superfans. She’s famous for dropping “Easter eggs” that hint at upcoming music; being a Swiftie is often akin to being Sherlock Holmes. And she’s a master of merchandise and vinyl that drive up the “ARPU” of a fan.

Vinyl is booming right now, buoyed by young people’s desire to own a physical token of their fandom (a proxy for community and belonging). In 2021, vinyl outsold CDs for the first time in 35 years. Half of the people who bought vinyl don’t even own a record player!

The most impressive stat? Last year, 1 of every 25 vinyl records sold in the U.S. was a Taylor Swift album.

In the startup world, we see the best companies productize “superfandom.”

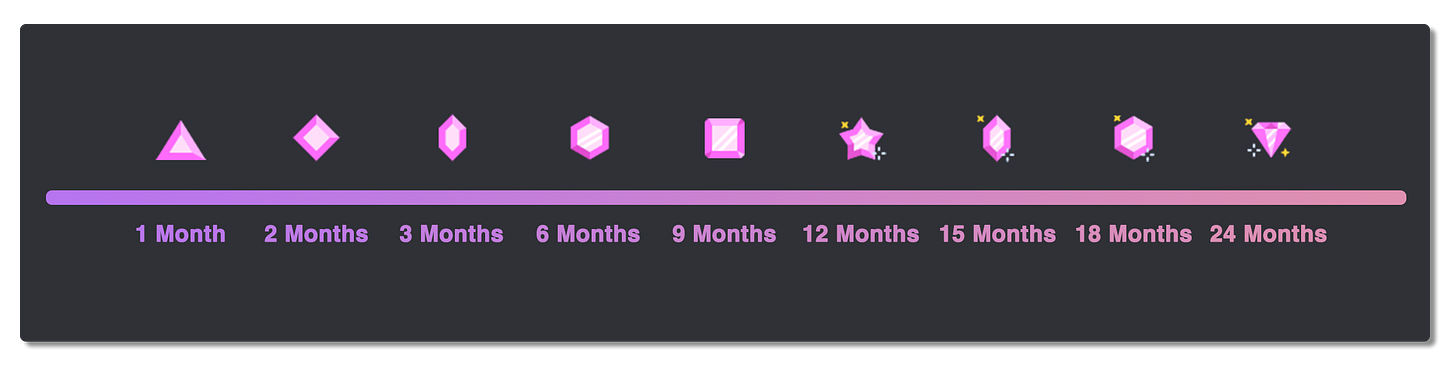

One example is a Streaks feature, which rewards users for daily engagement. Snap pioneered Streaks, which track how consistently two users chat with one another. The more days in a row friends chat, the longer their streak becomes. This feature cleverly encourages daily engagement—you don’t want to lose your streak.

In a social media context, Streaks can be viewed negatively; some critics argue that Streaks gamifies socialization to keep people addicted to social apps. But in other contexts, Streaks can encourage good behaviors.

Artifact, the new personalized news app from the Instagram founders, uses Streaks to tell users how many days in a row they’ve read an article. The better a user’s streak, the better Artifact will learn what kinds of articles to surface. Reading the news is a daily habit, and Streaks encourages that daily usage.

Duolingo, similarly, uses Streaks to celebrate a user’s consistency in language learning, also a space where daily engagement is key to success. I wrote last week about how revamping Streaks improved user retention at Duolingo.

We also see companies come up with products to recognize “superfans,” playing into people’s desire for status. Discord, for instance, monetizes through a paid subscription called Discord Nitro. Nitro users are Discord’s power users—the people willing to pay for customized profiles, bigger uploads, and HD video. Discord rewards Nitro subscribers (and other power users) with badges that signify a user belongs to Nitro and how long a user has subscribed. Badges are a smart and easy way to reward power users.

One of my favorite examples of a company rewarding its most loyal users: Chewy sends pet owners free, personalized portraits of their pets.

It’s a nice touch that probably ticks up retention by a few points (at least a few basis points). When a pet owner loses her pet, Chewy is also known to send a letter of condolence.

Doing things that don’t scale with your best customers is good business. Not only do you gain further goodwill with the people who are your biggest evangelists, but, if done correctly, you generate meaningful word of mouth and earned media value. The fans who attend one of Swift’s Secret Sessions will tell everyone they know about it for years; Secret Sessions, and how Taylor treats her fans, become part of fandom lore. The customer who gets an unexpected pet portrait from Chewy will share it on social media and offer Chewy free marketing. Thoughtful engagement of superfans pays dividends.

Final Thoughts

Last year, NYU announced a class on Taylor Swift. This week, Stanford followed suit. They may be on to something.

The people who power pop culture can be blueprints for the companies that need to tap into the zeitgeist to break through. Swift is one of the first internet-era pop stars, and she’s a masterclass in brand-building and community management.

Enduring companies are nimble and agile, able to stay embedded in culture—Apple, Nike, Disney. The best startups are similarly finding creative ways to stay modern and to constantly reinvent themselves—Figma and Notion, Snap and Duolingo.

Two years ago, I wrote Lil Nas X Is Gen Z’s Defining Icon to examine what we could learn about Gen Z behavior through the example of a leading Gen Z superstar. Taylor Swift is another example of a pop culture mainstay who embodies aspects of 21st-century business. Many companies would benefit from taking a page out of her book.

Sources & Additional Reading

Acquired has a terrific episode on Taylor Swift’s career, as of January 2022. Warning: it’s long (nearly 3 hours!) but it’s a great listen.

Contrary has a great research report on Common Room

Here is Bill Gurley’s piece on market sizing mentioned above

A deep-dive into how Notion cultivates community from Decibel VC

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: