What the Analog Inventions of the 20th Century Teach Us About the Digital Inventions of the 21st

From Filing Cabinets to VR, Pneumatic Tubes to AI

This is a weekly newsletter about how tech and culture intersect. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

What the Analog Inventions of the 20th Century Teach Us About the Digital Inventions of the 21st

One of the unsung inventions of the 20th century was that of the filing cabinet.

In the 1800s, information was organized in pigeonhole desks. These were desks with a series of small holes that—you guessed it—were once nests for carrier pigeons. The problem with pigeonhole desks was that they proved more practical for birds than for paper: paper needed to be folded to fit into the holes, making it difficult to quickly organize and retrieve information.

At the turn of the 20th century, the vertical filing cabinet was invented. These filing cabinets, first made of wood and later metal, used mechanical systems that enabled drawers of up to 75 pounds of paper to open and close smoothly. They were a game-changer. Suddenly, people could easily retrieve paper records, which were becoming essential to modern life—health documents, school records, mortgage papers.

People created systems for organizing files using folders and tabs. The terms “folder” and “tab” have carried over to the digital age. The design of the browser, for instance, resembles tabs in a filing cabinet:

This is a form of skeuomorphism—how interfaces mimic real-world counterparts in order to be more intuitive for users—which we also see in examples like the ‘Save’ icon being a floppy disk, the calculator app being a calculator, and the trash bin being…well, a trash bin. These are all analog-to-digital examples. It’s interesting to think about the terms we use today in the digital age that will carry forward to future technologies. We may still say “download” in 2050, for instance, even though we may not technically be downloading anything. Or we may still say “app” or “homescreen” when those words no longer apply. More directly related to skeuomorphism, perhaps going to the movies in VR will resemble going to a physical movie theater, while autonomous vehicles will resemble modern cars, even though we could theoretically rethink aspects of their design.

Over the weekend, I went with my family to the Museum of the City of New York. The museum (which I highly recommend) has an exhibit dedicated to New York’s relationship with technology, focusing on 20th century analog innovations that transformed the city.

I’d group the innovations into three broad buckets—technologies focused on the:

Production of Content & Information,

Organization of Content & Information, and

Access to Content & Information

This same framework can be applied to our current moment in technology and to where we might be going. Just as I viewed the museum exhibit and was stunned by how far we’ve come since the 1950s, I imagine someone in 2090 will be similarly stunned by how things looked in the 2020s.

In this week’s piece, I’ll look at some of the analog technologies that paved the path to modern day, and then how those same broad themes can be carried forward into future innovations.

Production of Content & Information

In the 1900s, New York became a global hub for media: the newspaper, radio, and magazine industries each had their hearts in the city.

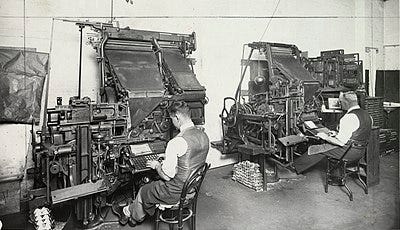

In the early part of the century, producing a daily edition of the newspaper was a herculean task. Newspaper companies—led by The New York Times—relied on breakthrough innovations like the linotype machine. The name of the linotype—an enormous, hulking contraption—comes from the fact that it could produce an entire line of metal type at once. Line-o’-type = linotype. Before the linotype’s invention, newspapers had to manually typeset letter by letter using a composing stick. If you don’t know what a composing stick is, I don’t either—but it sounds very, very painful and slow.

The linotype accelerated newspaper production. By 1920, New York had 15 daily papers in English and dozens more in foreign languages (the city’s population was 41% foreign-born at the time).

In the 21st century, we’ve again seen innovations accelerate the production of content and information. It’s now been over two years since I made this graphic, but it still captures the arc toward democratized video creation tools:

It’s becoming easier to create quality content without specialized knowledge or expensive equipment. Standalone apps like the free editing app CapCut further push forward ease of production: CapCut, which powers hundreds of TikTok trends, was the 9th-most-downloaded app globally in 2021 with 255M downloads, wedged between #8 Messenger and #10 Spotify. (CapCut is also owned by Bytedance, after Bytedance bought CapCut’s predecessor, Viamaker, for $300M in 2018.)

This trend of democratized production is years in the making. Back in 2015, Steven Johnson wrote in The New York Times:

The cost of consuming culture may have declined, though not as much as we feared. But the cost of producing it has dropped far more drastically. Authors are writing and publishing novels to a global audience without ever requiring the service of a printing press or an international distributor. For indie filmmakers, a helicopter aerial shot that could cost tens of thousands of dollars a few years ago can now be filmed with a GoPro and a drone for under $1,000; some directors are shooting entire HD-quality films on their iPhones. Apple’s editing software, Final Cut Pro X, costs $299 and has been used to edit Oscar-winning films. A musician running software from Native Instruments can recreate, with astonishing fidelity, the sound of a Steinway grand piano played in a Vienna concert hall, or hundreds of different guitar-amplifier sounds, or the Mellotron proto-synthesizer that the Beatles used on ‘‘Strawberry Fields Forever.’’ These sounds could have cost millions to assemble 15 years ago; today, you can have all of them for a few thousand dollars.

This is pretty remarkable. And it continues to hold true: Parasite, the 2020 Best Picture winner and my current answer for favorite movie (it changes every week), was cut on Final Cut Pro.

The same concept extends to 3D creation. Minecraft and Roblox have broadened the definition of game developer. Overwolf makes it easy to build in-game apps and mods.

And we’re now seeing AI drive a Cambrian explosion in creativity. Jasper.ai, Copy.ai, and Lex give writers superpowers. Midjourney lets anyone with a Discord account create beautiful AI-generated images—and v4 is dramatically better than v3. As my colleague Cat shared last week, in these v3 (left) and v4 (right) outputs for the same prompt—“A penguin in Venice”—we get much better results in v4. We no longer have penguins with two beaks and three legs.

Ben Thompson had Midjourney’s David Holz on Stratechery recently for an interview. Holz shared that about 10% of cloud costs are going into training, while 90% are going into the inference to the users making images. Midjourney is using more than 10,000 GPUs, making it one of the largest GPU users in the world.

I found this excerpt particularly interesting:

Holz: Our inference usage is weird in that some users are willing to wait and some don’t have to wait and some won’t wait. And then there’s a large latency, but the usage pattern is really weird. So we did a lot of innovative logistics stuff early on to make the costs low. So right now, if you make an image, there are eight different regions of the world that the image might get made in, and you have no idea. It might get made in Korea or Japan or the Netherlands or something. It’s going to eight different regions that the GPUs are balancing between. Where it’s really cool is because we’ll use a lot of the GPUs in Korea while it’s nighttime and everyone’s sleeping there, no one’s using them. We can kind of load balance. You can basically race the darkness of the night across the earth.

We’re still in the early innings of AI applications, and every year leaps are being made. GPT-3 came out less than three years ago with ~200 billion parameters; the upcoming GPT-4 has ~1,000,000,000,000 (a trillion) parameters. AI will accelerate production by an order of magnitude, just as analog technologies like the linotype accelerated production a century ago.

At the same time, AI-powered production will converge with more immersive forms of content, like VR and AR. (One of my favorite quotes is Epic Games’s Tim Sweeney on VR: “I’ve never met a skeptic of VR who has tried it.”) The next decade will see a proliferation of information and content unleashed by new tools.

Organization of Content & Information

We already covered the creation of the filing cabinet, which was essential to organizing information. A related invention was that of the index card. Before index cards, information was stored in cumbersome bounded ledgers. Around the turn of the century, information management via cards of uniform size and weight took hold; cards were stored in drawers, each representing one unit of information, and could be arranged sequentially or alphabetically.

Founded in 1895, The New York Public Library became the city’s central nervous system of knowledge. The largest free public library system in the country, it housed eight million books and one million items of research by 1913, using recent innovations like the Dewey Decimal system to catalog everything. The card-based systems underpinning the library were the databases of the analog age.

An early version of a search engine, meanwhile, took place at The New York Times headquarters. Staff on the second floor fielded phone calls from a curious public, providing answers to their questions. One clip, for instance, shows a woman answering a call from a member of the public.

“Which player had the highest batting average this year?” the caller asks.

“That would be Bill Terry, at .401,” the woman replies.

The caller thanks her and hangs up. Seventy-odd years later, Google emerged. And now, as Google turns 24, many young people instead turn to TikTok and Instagram for search: 40% of Gen Zs prefer searching TikTok and Insta over Google.

Google’s mission, famously, is “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” New technologies are organizing information in fascinating new ways. One of our portfolio companies at Index, for instance, is Hebbia. You can think of Hebbia as Ctrl + F for contextual search. Instead of needing an exact match, you can ask Hebbia a question. Imagine an investment banking analyst trying to sift through an SEC filing to figure out reasons revenue is down; using Hebbia, the analyst can just type in the question.

You can read more about Hebbia from my partner Mike here, and from The Information’s recent profile of George Sivulka, Hebbia’s founder and one of my favorite people.

As remote and hybrid work surge, meanwhile, we see knowledge management become central to companies: software like Guru, Notion, and Tango facilitate better organization of company content and information.

We’ve come a long way from index cards and public libraries. We’ve even come a long way from Google, the most successful company to emerge from the late-90s tech boom. It’s becoming easier and easier to organize vast quantities of information, and relatedly, to make that information readily accessible. Which brings us to…

Access to Content and Information

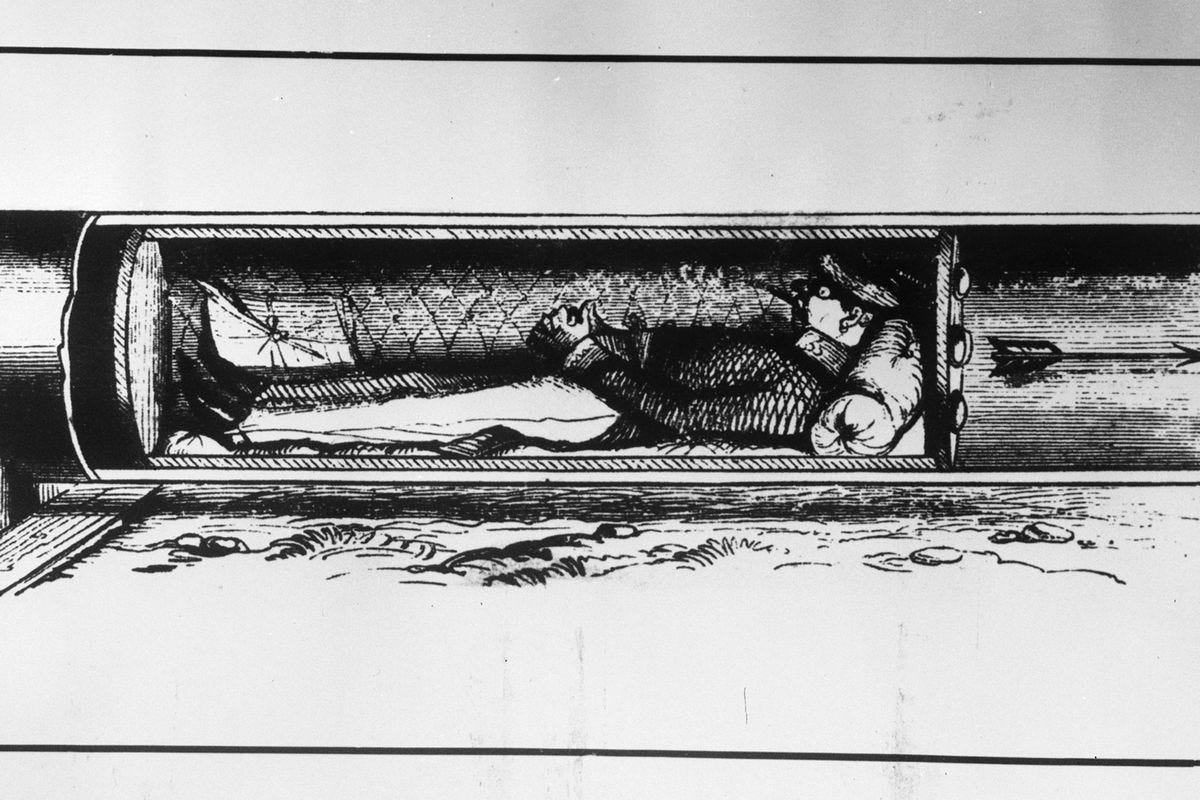

One of the forgotten eras of analog technology was the era of the pneumatic tube. Pneumatic tubes use compressed air or a vacuum to move capsules—and New York City ran on them.

Pneumatic tubes were actually originally intended to move people: one early New York demonstration sold 400,000 rides through a block-long human-sized tube. But moving people soon proved impractical (and dangerous), so pneumatic tubes focused on moving packages.

The tubes became staples in postal offices for moving mail and in hospitals for moving lab specimens and test results (some large hospitals still use them today for this purpose). Once, a sick cat was even sent through a pneumatic tube to a veterinarian.

As E.B. White wrote in 1949’s Here Is New York:

It is a miracle that New York works at all. The whole thing is implausible. When a young man in Manhattan writes a letter to his girl in Brooklyn, the love message gets blown to her through a pneumatic tube—pfft—just like that. The subterranean system of telephone cables, power lines, steam pipes, is reason enough to abandon the island to the gods and the weevils…

The distribution of content and information (and physical goods) has come a long way. Fax machines soon emerged. Then the internet came along and blew everything up.

You could argue Hebbia fits better in this bucket—and Hebbia certainly improves access to information, in addition to organization. But another interesting vector is broadening access by crowding in more content and information in the first place. There’s a lot of latent knowledge out there, and we’re now seeing startups work to unlock it. Reforge is building an “expert economy” to learn from world-class functional leaders in categories like growth marketing and product management. Office Hours lets you book time with an expert to tap their specialized knowledge. And Tegus offers a repository of company intelligence—thousands and thousands of transcripts with experts.

AI applies here too: in the old days, you might need to learn a new language through Duolingo or even a live human tutor; now you can turn to Speak and get instant feedback from an AI tutor.

Access is being approved—both in how we tap into pre-existing information, and how we expand the pool of information that’s out there.

Final Thoughts

Why does any of this matter? Technologies of the moment have far-reaching impacts on how people live and work. One example—

In 1950, 342,000 Americans worked as telephone operators for the Bell Telephone network—and another 1,000,000 worked for private phone operator companies. The US population at the time was ~150 million, meaning about 1 in 100 Americans (and 1 in 60 members of the labor force) worked as a phone operator. That’s a roughly equivalent portion to the share of the modern workforce employed by Walmart, the nation’s largest private employer.

But by 1984, the telephone was shifting to automated systems, and national employment was down to 40,000. By 2020, fewer than 2,000 Americans were employed as telephone operators (and I’m sure we’re all wondering why we still need 2,000 phone operators).

The transition from analog to digital transformed labor markets. We’ll see a similar shift with new technologies reinventing how people work. The Institute for the Future predicts that 85% of the jobs that today’s students will have in 2030 don’t yet exist. That seems far-fetched, until you consider jobs that have emerged in the past decade or so: drone operator, social media manager, app developer, cloud computing engineer.

The analog technologies above were groundbreaking at the time, but were rendered moot by the onset of the digital age. We’re now progressively moving through digital eras: mobile, cloud, AI. The same frameworks from the innovations of the 20th century can be applied to the innovations of the 21st. The arc of technology bends to more production, better organization, improved access. The arc has bent that way for hundreds of years, and it will continue to bend that way—likely even more rapidly and more dramatically as the pace of change accelerates.

Sources & Additional Reading

Check out the Museum of the City of New York—it’s well worth a visit

Read about Hebbia and George Sivulka in The Information

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: