Weekly writing about how technology shapes humanity and vice versa. If you haven’t subscribed, join 50,000 weekly readers by subscribing here:

When AI Begins to Replace Humans

One way to track the state of technology—CAPTCHAs.

CAPTCHA stands for Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart. You probably remember their first iteration, when you were asked to decipher squiggly, hard-to-make-out words.

And we’ve all clicked the faintly-dystopian button, “I’m not a robot.”

CAPTCHAs come from the company reCAPTCHA, which was founded in 2007 by Luis von Ahn—a Carnegie Mellon graduate researcher—and later sold to Google in 2009. What many don’t realize is that those squiggly words you typed were helping to digitize old books. Typically, the distorted word that was given to you in an early CAPTCHA was a word from an old text that had stumped a computer. If enough people identify the hard-to-read word as “dog,” for instance, then the word would be confidently deciphered as dog and the CAPTCHA would move on to a new word.

In 2007, reCAPTCHA partnered with The New York Times to help digitize 100 years of the newspaper’s archives. And after buying reCAPTCHA, Google supercharged the company so that CAPTCHAs were soon deciphering the equivalent of two million books a year (!). As the cherry on top, two years after selling reCAPTCHA to Google, Luis von Ahn founded Duolingo. He’s still CEO today.

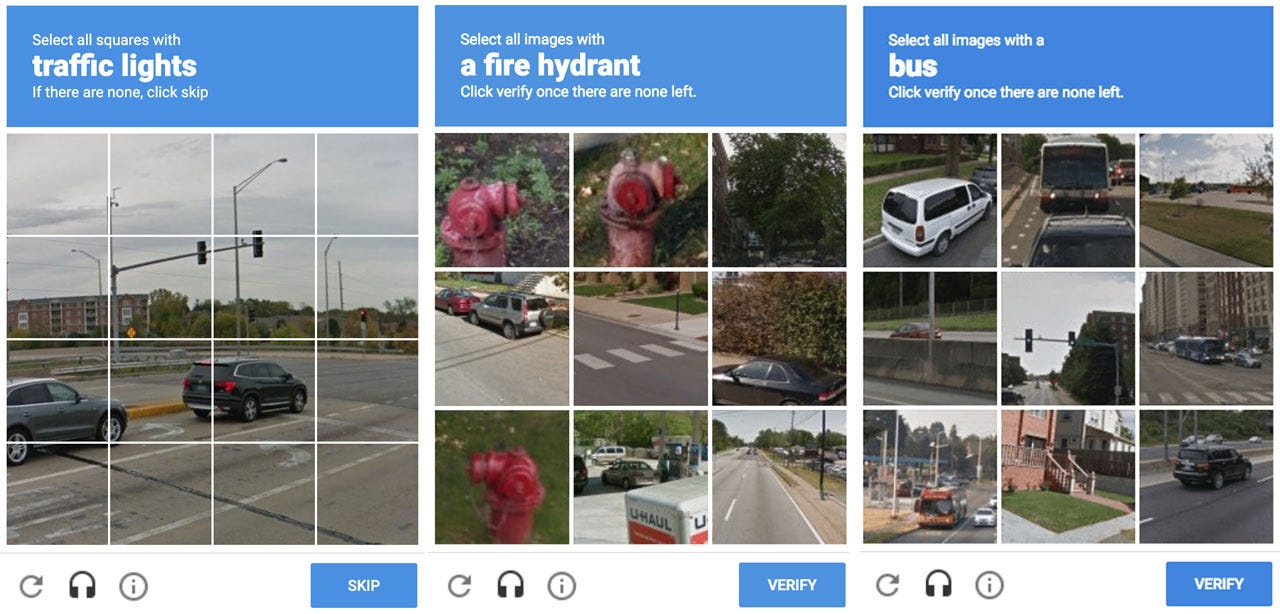

CAPTCHAs no longer give us distorted words. We’re all familiar with their new iteration, selecting tiles of traffic lights and crosswalks and vehicles.

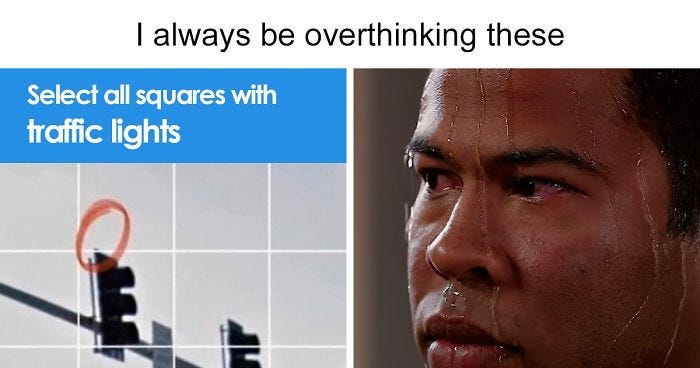

This experience is so universal to being online that it’s become the source of countless memes.

The question below led to a heated debate on Quora—after all, are the poles part of the traffic light? 🤔

Of course, there’s a reason reCAPTCHA (and Google behind the scenes) is asking us to identify traffic lights. As with digitizing old books, there’s a hidden purpose. This time, billions of people are helping Google train its AI. Each time you identify a bicycle, you’re helping improve Google’s image recognition abilities. This proves critical for Google, particularly in its self-driving car efforts. (That’s why we see so many street-related objects like crosswalks and traffic lights!🚦)

The effort has paid off: Google’s image recognition capabilities are now about 20% better than a human’s.

CAPTCHA was born with a single purpose: How do we tell humans and computers apart?

Rarely has a question been more timely or pressing. Countless schoolteachers across America are struggling to differentiate student-produced essays from ChatGPT outputs. The Quora question above led to well-written responses from humans, but also a ChatGPT response that could easily pass as human writing. (Quora has partnered with ChatGPT and given the chatbot valuable real estate on its site.)

CAPTCHA’s early iteration mirrored the early purpose of the internet: translating offline information into online information. The internet was about aggregating and then indexing all human knowledge. Fittingly, Google was the primary beneficiary of that first epoch, owning the indexing portion with online search—arguably the greatest business model ever developed.

CAPTCHA’s newer iterations mirror more recent uses of technology—powerful AI models that are now consistently better at uniquely-human tasks than actual people. The solid lines in this chart show how AI performs against human benchmarks (the dotted lines) of image classification and reading comprehension:

Last week’s piece showed a similar visualization from Visual Capitalist:

The irony with recent CAPTCHAs, of course, is that humans have been training AI to, one day, render humans obsolete. (Gasp!)

That’s the dramatized version—in reality, automating humans isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Many tasks are rote and thankless, and automating those tasks frees up humans to tackle more complex and rewarding efforts. But the sheer pace of AI’s improvement is scaring people. A new survey from Gallup found that 22% of American workers now fear AI could replace them, up from 15% in 2021. AI fears among workers without college degrees remain consistent at ~20%, while AI fears among workers with college degrees went up dramatically—from 8% to 20% in two years.

This week’s Digital Native dives into how AI might replace humans, and what the ripple effects will be. I’ve broken it into three parts:

Worker Displacement

AI-Native Marketplaces

AI-Native Productivity Software

Worker Displacement: The 10,000-Foot View

Even pop stars aren’t safe from AI automation.

This summer, Warner Music Group signed its first AI act, a computer-generated performer named Noonoouri. Noonoouri, who boasts 405K Instagram followers, has been called “the first-ever strictly digital pop star.” Her singing voice is created using generative AI that’s been trained on real human voices.

Of course, Noonoouri is an exception to broader automation, albeit a fascinating one; most of the jobs that AI automates won’t be in pop music. Taylor Swift and Beyoncé are probably safe for now.

It’s everyday people who face the brunt of automation. Goldman Sachs Research estimates that generative AI exposes 300M full-time jobs to automation, with two-thirds of current jobs exposed to some degree of automation. Here’s a visualization of the industries that Goldman expects to be most-impacted. Administrative office work, legal work, and architecture & engineering lead the way.

We’re already seeing startups tackle these areas. To take the top two categories: Xembly is a startup that gives everyone an automated executive assistant to schedule meetings and summarize calls, while Harvey serves lawyers, helping with contract analysis, due diligence, litigation, and regulatory compliance. (AI coming for high-powered fields like law helps explain the jump in college-educated anxiety shown in the Gallup poll above.)

For comparison, here’s the extent of automation Goldman expects across industries:

If you work in maintenance, repair, or construction, you’re pretty safe. If you work in admin or legal, you have a ~40% chance of being replaced by AI. (One interesting trend: Gen Z has a high opinion of skilled trades like plumbers and electricians. A recent survey found that 73% of Gen Zs say they respect skilled trade as a career, putting it second only to medicine (77%); 47% were interested in pursuing a career in a trade. One potential reason: 74% say they believe skilled trade jobs won’t be replaced by AI.)

Last spring’s AI State of the Union covered automation in more depth, pointing out that this is a story we’ve seen unfold before. From that piece:

Many modern jobs will soon seem like distant memories. We’ve seen the same patterns in past technology epochs. Before there was automatic equipment to reset bowling pins, “Bowling Pin Setter” was an actual occupation. Ditto for “Lamplighter”—Lamplighters walked on average 10 miles per day, lighting lamps before dusk and distinguishing them at dawn. Will jobs like Executive Assistant, Copywriter, or Accountant follow the same extinction?

The silver lining: worker displacement from automation has historically been offset by the creation of new jobs. We’ll see jobs emerge that we can’t even think up yet (“Prompt Engineer” seems to be an early, and lucrative, example). Who would have thought 30 years ago that jobs like Cybersecurity Analyst, Database Administrator, or Machine Learning Engineer would exist? Let alone Social Media Manager, SEO Consultant, or Discord Community Manager?

This is a familiar cycle in technology.

Let’s go back to the first era of the internet, the era in which we deciphered old books and newspapers with our CAPTCHAs. That era killed a number of jobs. “Encyclopedia Salesman” and “Yellow Pages Deliveryman” were real jobs; now, those jobs are largely deceased, yet 150,000 people work at Google “to organize the world's information and make it universally accessible and useful.”

Likewise, “Travel Agent” was mostly killed by sites like Booking.com, Expedia, and Airbnb; “Radio Shack Attendant” was killed by iTunes and then Spotify; and “Film Developer” was killed first by digital cameras, and later by the rise of mobile phones.

The question is—will Executive Assistant go the way of those jobs?

Think of the tasks an EA handles: calendar scheduling; researching office space for the company; finding a good private dining room for the company dinner. Within a few years, it wouldn’t be surprising to see each of these executed more quickly (and more economically) by a chatbot: “Give me 10 options for office space in Lower Manhattan that’s available starting October 1st, would fit our 15-person team, and is under $15K-a-month.” Our kids might be alarmed to learn that humans ever took on such tasks.

The job of an EA may instead morph more into a job more akin to a Chief of Staff, shifting the role to more complex tasks that demand human involvement.

What are the startup opportunities here?

Many jobs will be partially automated, receiving an AI “copilot.” The paralegal’s copilot will help her draft more briefs; the tax advisor’s copilot will help him serve more clients during tax season; the engineer’s copilot (fittingly called GitHub Copilot) will help her code better and faster. Other jobs may soon be completely replaced by “vertical AI” solutions that are a next-gen version of vertical SaaS.

I expect the jobs that are automated first to be the jobs that are lower-paid and lower-importance (in terms of dollars at stake; i.e., how costly is a mistake?). Things might move something like this:

The jobs in these boxes aren’t perfect (architects, don’t come at me!), but you get the point. And I might be wrong here; maybe more highly-paid roles are the first to go, given the money they free up for comanies. Either way, roles like “physician” will likely be in the “copilot” category, with meaningful human involvement, potentially forever. Though how many patient visits can be replaced by AI? After all, one study found that ChatGPT outperforms real-life doctors in giving medical advice, and another found that AI has better “bedside manner” than human physicians.

Either way, we’ll need tremendous workforce retraining. Many companies are being founded to build AI infrastructure and AI applications, but I’ve seen far fewer companies building solutions for us to quickly upskill our workforce to offset massive AI-related job loss. Only 0.1% of GDP is spent on helping workers retrain, less than half of what was spent 30 years ago, meaning we’ll have to rely on the private sector to come up with solutions—and fast.

The next two sections are brief snapshots of how two of the most attractive business models in technology might be impacted by AI replacing humans.

AI-Native Marketplaces

Marketplaces are an elegant business model. At its simplest, the classic two-sided marketplace connects two parties to deliver a product or service. Often, one or both of those parties is a human—Airbnb, for instance, connecting a guest and a host, or Uber connecting a passenger and a driver.

But what happens when one party is an AI?

This may be especially present in services marketplaces, which remain less-developed than product marketplaces. I like this visualization from Dan Hockenmaier, a marketplace guru who works at Faire:

None of the 10 public U.S. marketplaces with $10B+ market caps are in services (you could make an argument for Uber, but that’s about it); none of the 10-largest private marketplaces are either. As Dan puts it, “You can buy a lightbulb in one click on Amazon, but hiring an electrician is still about as hard as it was 100 years ago.”

This is because services are more diverse than products, and thus more difficult to categorize. Services also include humans, leading to a lot of back-and-forth. Anyone who’s tried to hire a plumber on Thumbtack, a furniture-assembler on TaskRabbit, or a housecleaner on Handy understands this: 37 messages later, and you’re still trying to pin down the person who can come on Thursday and do the job for under $100.

AI will first reinvent marketplaces by helping with the matching process; LLMs trained on those 37 messages (multiplied by millions of customers) can get very good at delivering the best service-provider quickly. This should unlock innovation in service marketplaces.

But what also interests me is the service marketplace that matches you to AI. Many services are vulnerable to automation. Tutoring; web design; translation; animation; website creation.

Today on Fiverr, I might search for a logo designer to make a new logo for Daybreak. What if a marketplace instead matched me with an AI who could do the job cheaply and effectively. The demand-side is still a human, but the supply-side becomes AI.

AI-Native Productivity

Productivity software has felt stale in recent years—there are only so many wall-to-wall products like Slack and Notion, or category-winners like Figma (design) and Gong (sales). Each of those companies is 8+ years old. What’s more, it’s challenging to compete with Goliaths like Microsoft Office 365 (345M paid users) and Google Workspace (3B users, including paid and unpaid).

But AI injects a new “killer feature.” As Seth Rosenberg points out in a good piece on product-led AI, Microsoft dominated spreadsheets with Excel for years. Then Google came along with a worse product, Google Sheets, but nailed the one feature that mattered most: real-time collaboration. Figma did something similar in design, catching incumbents and startups alike flat-footed.

Real-time collaboration is now table-stakes. But what happens when AI is front and center?

Take slide decks, a staple of the business world that we all love to loathe. PowerPoint has some nifty new tricks, but AI is far from front and center. The startup Tome, meanwhile, is built entirely around AI. I remember Tome’s founder, Keith Peiris, once telling me, “Slide creation and storytelling should be an order of magnitude easier.” AI fulfills that vision. Playing around with making a slide deck in Tome, I first asked a slide to add an image of a dog.

A few seconds later, I got the output:

A slide later, I asked for a few bullet points about why AI will change productivity software.

The result:

Productivity software has stagnated for a few years, treading water. But thinking AI-first—building the entire product experience around what’s now possible, a new killer feature—creates an Innovator’s Dilemma for incumbents and an opportunity for startups. Every category becomes ripe for reinvention.

Final Thoughts

Ultimately, we should lean into inevitable technological displacement.

How should teachers respond to AI in classrooms? Rather than using (unreliable) software to assess whether a student used AI in an essay, a teacher should rethink how she teaches: perhaps she assigns students to write an essay using ChatGPT—a tool they’ll have in the real world, by the way!—then in the classroom students analyze, dissect, and critique the ChatGPT essay. Math instruction had to evolve to react to the invention of the calculator; English instruction (among every other subject) will need to evolve to react to improvements in AI.

AI means massive worker upheaval over the next few years. Many people will get AI copilots that make them faster and more effective at their jobs—though it’s unlikely this means fewer hours worked, and more likely this means higher productivity and greater GDP growth. (Remember that in 1930, John Maynard Keynes predicted that because of innovation, we’d all be working 15 hours per week in 2030. Whoops.) Many other people will lose their jobs together. We’ll need widespread workforce development to mitigate the pain of job loss.

It’s also interesting to think about what AI-native companies will be born to challenge incumbents. Marketplaces and prosumer SaaS are two business models that have powered much of startup value creation over the past 10 years—how do their AI-first iterations compare? In all likelihood, incumbents are in for another reckoning and more value creation to startups is yet to come.

Sources & Additional Reading

Seth Rosenberg had a great piece on product-led AI

Here’s Dan Hockenmaier’s piece on services marketplaces

Rachel Stonecraft had a great video about CAPTCHA on the Index TikTok; this New York Times piece covers reCAPTCHA’s partnership with The Times

Related Digital Native Pieces

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: