This is a weekly newsletter about how tech and culture intersect. To receive Digital Native in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

When Art and Technology Collide

Back in February, I wrote a piece called The Art of the Deal. That piece was about how money shapes art, and it began by tracing the origins of the modern art market:

The modern art industry can be traced back to October 18, 1973.

That day in history has become known as “the Scull sale”—the day that Robert Scull, a New York taxi-fleet magnate, auctioned off his prized art collection for an outrageous and (to many) offensive sum. Scull sold 50 of his most prized works at a Sotheby’s auction. Brazenly, Scull—a talented self-promoter—marketed the event as a must-see attraction. The New York art community was horrified. Art had never been so financialized; the art world had never seen such prices. Jasper Johns’s “Target”, for instance, sold that day for $135,000. (The painting is currently owned by Stefan Edlis, who bought it in 1997 for $10 million and who says it’s now worth $100 million.)

That October day was the day that, in many ways, art became about money. Or, at the very least, the two became even more inextricably bound.

Last year was a banner year for the intersection of art and money, with the explosion of NFTs and with digital art as their first mainstream use case. It’s hard to believe that it’s been 18 months (18 months to the day, in fact, as of Monday) since Beeple sold his collection of NFTs at Christie’s for $69 million.

The rise of digital art—and rampant speculation in the NFT markets—posed interesting questions: What is art? What makes a piece of art valuable? Those questions were the focus of the piece in February, and money and art continue to intermingle in fascinating ways. (Fine art is an emerging asset class, in fact, led by startups like Masterworks.)

But this week’s piece focuses on a different intersection—the intersection of art and technology. The intersection of art and tech has flavors in NFTs and digital art, of course, but the collision is even more timely in 2022 due to the arrival of mainstream AI-generated art.

There are three players to know: DALL-E, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion. Let’s quickly tackle each, and then unpack some of the ramifications of AI art.

DALL-E

The two most prominent large language models are from OpenAI and Google. Google’s image generation model, Imagen, is closed off, but OpenAI’s model, DALL-E, can be accessed through OpenAI’s controlled API. DALL-E (now DALL-E 2, to be specific) has become something of a sensation this year, kicking off the mania around generative art. (The name DALL-E, by the way, is a portmanteau of the artist Salvador Dali and the Pixar character WALL-E.)

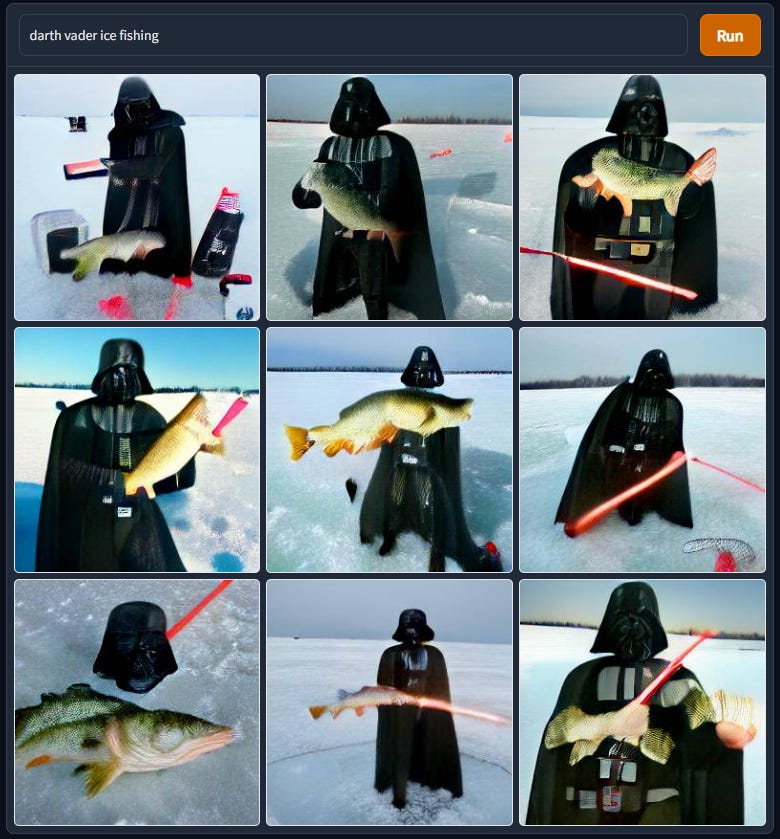

One of my favorite Twitter accounts is Weird DALL-E Mini Generations (shoutout to my colleague Erin for first showing it to me), which showcases some of the…odder examples of DALL-E’s AI creations. For instance, here’s what DALL-E produces for the text prompt “darth vader ice fishing”—

And here’s what DALL-E produces for “Donald Trump Big Bird mask”—

You can spend hours perusing the text prompts people dream up on the Twitter feed.

Midjourney

After DALL-E got things started, Midjourney came along this summer and shook things up. Midjourney exists on Discord: anyone can sign up for a free account and get 25 credits, with images generated in a public server. (You can join the Discord here.) After you exhaust your 25 credits, you pay either $10 or $30 a month, depending on the number of images you want to create and whether or not you want them to be private to you.

Midjourney has rapidly become one of the most popular servers on all of Discord, with 2 million members. This has thrust text-to-image AI into the mainstream, which was all part of the plan for Midjourney’s founder David Holz. Holz told The Verge last month (in an excellent interview worth reading in full): “A lot of people ask us, why don’t you just make an iOS app that makes you a picture? But people want to make things together, and if you do that on iOS, you have to make your own social network. And that’s pretty hard. So if you want your own social experience, Discord is really great.” Launching on Discord was Holz’s way to make text-to-image AI a mass-market phenomenon.

Much of Midjourney’s art is stunning. Here are some snippets from the Community Showcase:

If you hover over an image in the showcase, you see the text prompt that led to that image. For instance, the prompt in the bottom right image here is “Tiny cute adorable Giraffe | Bobble Head | Pixar Style | Dramatic lighting”—

I’d say he fits that description 🦒

Here’s what Midjourney produces when I try to replicate the Digital Native logo, which is a Bitmoji of me scrolling through my phone.

Not bad. I probably could’ve been more specific—“wearing a blue shirt” for instance—but you get the point.

My partner and I recently moved into a new apartment in New York. Say we want some art for our wall that showcases our new neighborhood. Here’s what the output might look like:

I recommend going into Midjourney and experimenting with your own text prompts. When you do so, you’ll likely experience a technology moment akin to the first time you used an iPhone—a delightful, magical experience that makes you go, “This is going to change everything.”

Stable Diffusion

As Midjourney began to steal DALL-E’s spotlight, Stable Diffusion came along and threw down its own gauntlet: like Midjourney, Stable Diffusion is free—but Stable Diffusion is also open source, and its models can be run on your own computer.

Stable Diffusion, which comes from the company Stability AI, was trained on three massive datasets with over 2 billion images. While DALL-E and Midjourney have content guardrails, Stable Diffusion has none: predictably, deepfake nude celebrities, pornography, and violent images have ensued, which caused Reddit to shut down many Stable Diffusion communities.

A report last week from programmers Andy Baio and Simon Willison explored 12 million images from Stable Diffusion’s dataset (a small but insightful subset of the 2 billion) and found that 50% came from just 100 websites, with a million alone coming from Pinterest. Much of the concern around Stable Diffusion stems from the fact that most images feeding the model are being used without permission, with the artist or photographer not receiving any compensation—or, often, not even knowing his or her work is being used.

Destroyer of Human Creativity or “Engine for the Imagination”?

Each of the main three players takes a different approach to text-to-image generation. It’s interesting to compare how they each interpret the same prompt:

But all three play a key role in the heated and controversial debate around the technology. I like how Charlie Warzel framed it in The Atlantic: “AI art tools are evolving quickly—often faster than the moral and ethical debates around the technology.” This isn’t unusual: technology breakthroughs happen, and society struggles to keep up; cultural digestion, reflection, and action take time.

AI tools invite fascinating questions. For one, who is the artist of one of these creations? Is the AI the artist? Is is the developer of the AI the artist? Is the artist the photographer whose image informed the model? Or perhaps the artist is you, the person inputting the text prompt.

There’s no right answer, and there are good arguments for each case. The most compelling argument is that all of these parties are in-part the artist. We’ve come a long way from the straightforwardness of Van Gogh painting Starry Night. The future isn’t so cut and dried.

A lot of the hand-wringing from text-to-image generation comes from the idea that these tools will take away human jobs. The Atlantic’s Charlie Warzel—yup, same guy quoted above—went viral (in the bad way) when he used a Midjourney-created image for a piece he wrote on Alex Jones. The image was the result of the text prompt, “Alex Jones inside an American Office under fluorescent lights.”

The backlash was multi-faceted (you can read Warzel’s mea culpa here), but one key argument was that The Atlantic should have paid a human artist to create the image. Like many technological innovations, text-to-image AI will likely obfuscate many existing jobs. In his piece earlier this week, Ben Thompson likened it to how the internet disrupted destroyed the newspaper industry, putting millions out of work.

It’s scary to think about machines replacing human creative output. But I tend to take the glass-half-full lens when it comes to innovation; I’m a perpetual technology optimist. Tools like DALL-E and Midjourney and Stable Diffusion will greatly amplify human creativity.

This is how Midjourney’s Holz puts it:

We don’t think it’s really about art or making deepfakes, but — how do we expand the imaginative powers of the human species? And what does that mean? What does it mean when computers are better at visual imagination than 99 percent of humans? That doesn’t mean we will stop imagining. Cars are faster than humans, but that doesn’t mean we stopped walking. When we’re moving huge amounts of stuff over huge distances, we need engines, whether that’s airplanes or boats or cars. And we see this technology as an engine for the imagination. So it’s a very positive and humanistic thing.

An engine for the imagination.

It will still require skill to make high-quality art. Even with an iPhone in 1.2 billion hands, many people are still really, really bad photographers. iPhones can now be used to make feature-length motion pictures that nearly mirror in quality films shot on expensive professional equipment. But you still need to be a talented director to make something great. Steven Soderbergh used an iPhone to shoot an entire movie, but the movie’s quality owed more to the fact that Soderbergh has a lifetime of carefully-honed expertise than to the device he used.

There are major questions yet to work out—who gets credit for AI creations, who gets paid for them, when is it better to hire a human vs. when is it ethical to use AI. It will take years, maybe decades, to sort out answers that become viewed as even modestly acceptable to society.

But text-to-image AI tools are groundbreaking in how they equip humans with even more ways to create. I like how Ben Thompson puts it:

What remains is one final bundle: the creation and substantiation of an idea. To use myself as an example, I have plenty of ideas, and thanks to the Internet, the ability to distribute them around the globe; however, I still need to write them down, just as an artist needs to create an image, or a musician needs to write a song. What is becoming increasingly clear, though, is that this too is a bottleneck that is on the verge of being removed.

When the printing press was invented in 1440, it was hugely controversial. New technologies typically are. But over time, throughout newer and newer innovations, humans have become more connected and creative and empowered—the printing press, the phonograph, the video camera, the iPhone. Each augments us in new ways. It feels like we’re on the cusp of a new era—one with many unforeseen consequences lurking around the corner, but one that will unleash new levels of creativity.

Sources & Additional Reading

An Interview with Midjourney’s David Holz | James Vincent, The Verge

What’s Really Behind Those AI Art Images? | Charlie Warzel, The Atlantic

I Went Viral in the Bad Way | Charlie Warzel, The Atlantic

The AI Unbundling | Ben Thompson, Stratechery

AI Images | John Oliver

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: