Why the Tech Pessimists Are Wrong

4 Reasons to Be Optimistic About Technology

This is a weekly newsletter exploring how technology and humanity collide. If you haven’t subscribed, join 40,000 weekly readers by subscribing here:

Why the Tech Pessimists Are Wrong

There are two Black Mirror episodes I often think about when I think of artificial intelligence—or, more specifically, artificial human consciousness. One takes a more pessimistic lens (as is characteristic with Black Mirror) and one leans more optimistic.

The first comes from the “White Christmas” episode. A man (played by Jon Hamm) has a job training “cookies”—digital clones of people—as personal assistants. The way that cookies work is that a human’s consciousness is reproduced digitally, then stored in an egg-shaped device. That consciousness is then used to service your every need, Alexa-style: “What’s the weather? Order me more groceries. Call John.” The thinking goes, what better personal assistant than a digital reproduction of you?

The twist is that trainers need to first break the digital clone’s resolve. Jon Hamm’s character is training the clone for a woman named Greta, but Greta’s clone is stubborn. Greta’s clone thinks that she’s a real person; naturally, she won’t obey commands. Jon Hamm tweaks the tech so that years pass by for Greta’s clone, in just a few “real world” seconds. He breaks her will, and she gives in. She becomes subservient to real-life Greta, living in her kitchen and acting as her personal assistant.

The second Black Mirror episode is “San Junipero,” which looks at artificial human consciousness through a more rosy lens. In this episode, we learn that people about to die can upload their consciousness to a virtual world called San Junipero. San Junipero is a gorgeous, utopian place where people can live in their young, healthy bodies forever (the episode is filmed in Cape Town).

The episode focuses on two elderly women whose younger selves fall in love in the simulation of San Junipero. It’s a beautiful love story.

In the real world, their human bodies eventually die—but their consciousnesses live on in the simulation. The episode’s final shot shows how vast the technology powering San Junipero is: millions of “people” are stored in a massive warehouse, plugged in to their idyllic afterlife.

These two episodes capture two sides of a similar technological breakthrough: one side is foreboding, and the other wondrous.

Much of pop culture’s representation of tech has historically been dystopian, from Brave New World to Ready Player One, 2001: A Space Odyssey to Gattaca. The more recent Black Mirror continues the trend: “San Junipero” injects rare optimism in a series about technology’s dark side. (The show’s name comes from what our screens become when they’re turned off: black mirrors, showing us our dark reflections.)

But we’ve seen dystopian narratives move from the fiction realm to non-fiction. Newspapers and late-night TV skew toward the negative these days, writing scathing takedowns of tech. Some of this is warranted, of course: the scrutiny of social media is appropriate, for instance, and many of the anti-trust critiques against Big Tech have real merit.

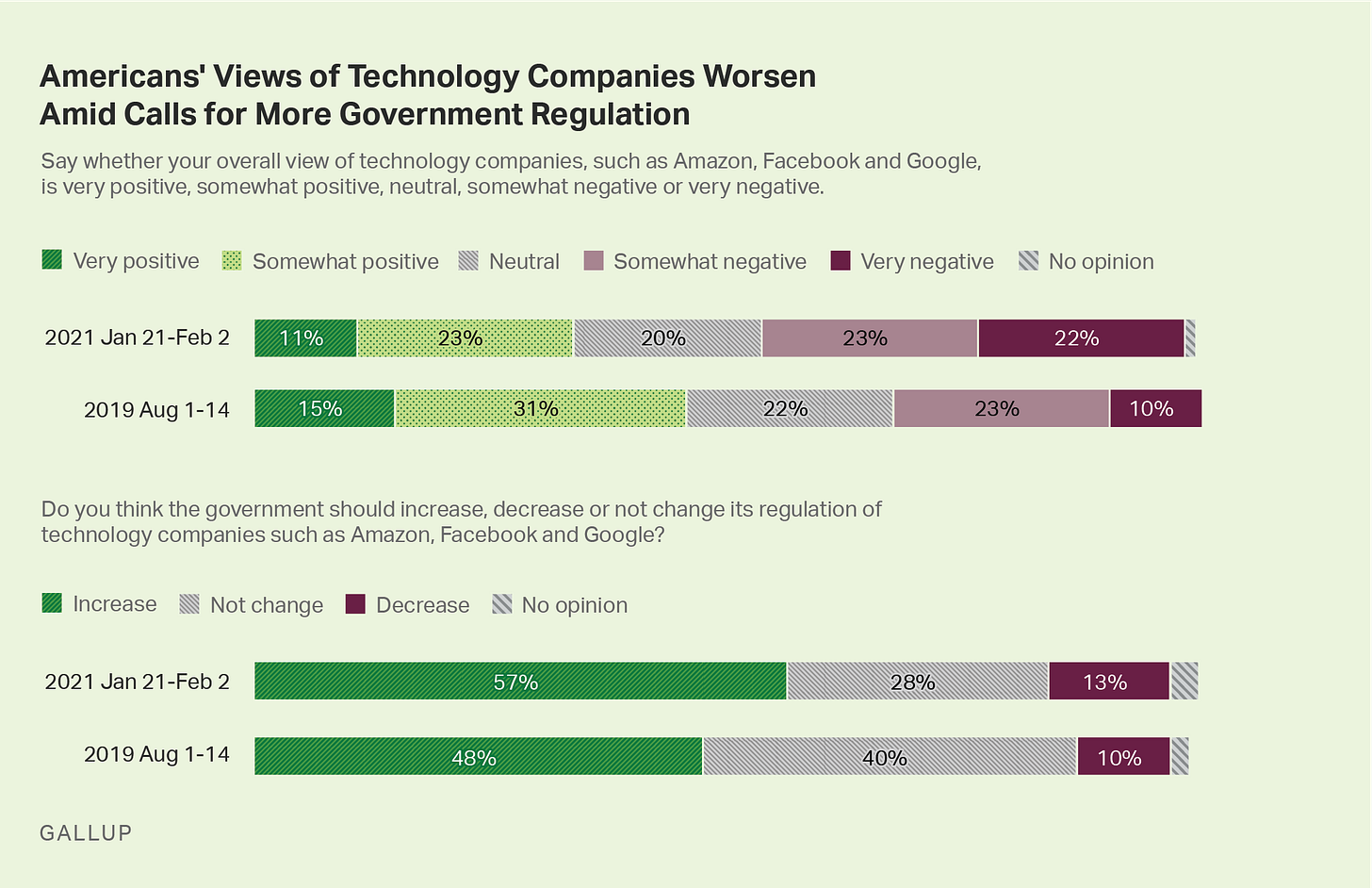

You can see the impact of negative media coverage in the data—polls of the American public show a sharply deteriorating view of tech:

Tech has swollen to 28% of the S&P 500, the index’s largest sector (Healthcare and Consumer Discretionary rank 2nd and 3rd with 13% and 12%, respectively). The digital revolution is the story of this century, and every company is reinventing itself with technology.

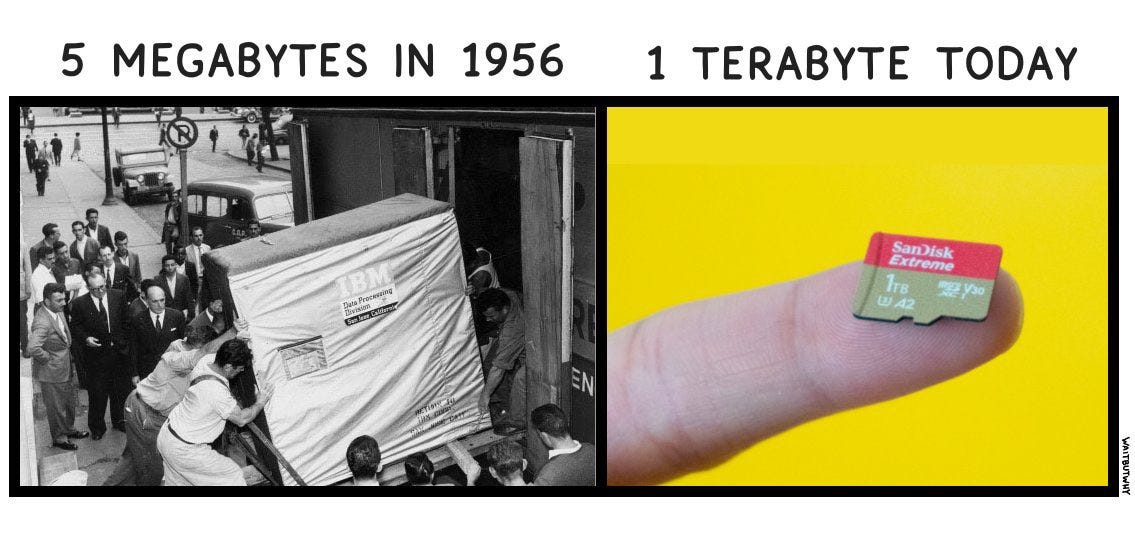

The pace of advancement is staggering. Below is a visual of 5 megabytes in 1956 vs. 1 terabyte today. (For context, 1 terabyte = 1,000,000 megabytes.) A terabyte hard drive in 1956 would’ve been the size of a 40-story building; today, it fits on your fingertip.

Rapid technological change leads to high highs and low lows. I like how Tim Urban frames it: new technologies in the 1900s brought billions of people out of poverty and saved millions of lives with innovations like the polio vaccine and penicillin. We got airplanes and radar and the computer. Yet we also got the atomic bomb.

What are the 21st-century equivalents? We have retinal implants and CRISPR, smartphones and augmented reality. Yet for many technology advancements, the jury is still out on whether they’re a net positive or a net negative: social media, virtual reality, artificial intelligence. Just as in the two Black Mirror episodes, there’s a duality to every innovation—an upside and a downside.

Today’s discourse tends to focus on the downside; what we’re lacking is the optimistic view of technology. And my view is that if you’re working in the startup world, you have to be optimistic. Things are changing so quickly, and every advancement brings with it shades of gray. But when you zoom out, the arc of technology is bending the world to the better.

There are some pioneering journalists reporting on technological progress. My good friend Cleo Abram, for instance, has a YouTube channel called Huge If True that chronicles the optimistic side of tech: artificial wombs and Starlink, electric planes and nuclear fusion. But we need more. We need to counteract the dystopian narratives of tech that are important to acknowledge, yes, but that are ultimately counterproductive at best and fearmongering at worst.

This week’s piece focuses on a loose framework I use to think about tech’s social impact. The four buckets here aren’t perfect, but they broadly capture four reasons I get excited about technology.

In short:

Technology amplifies creativity by giving creative people superpowers. Each of us can use new tools to better make things and express our ideas.

At the same time, tech amplifies productivity, particularly for knowledge workers. While creative tooling trends more right brain (visual and intuitive), productivity tools trend more left brain (logical and analytical).

Both of the prior buckets focus more on the individual. But we’re social animals, and technology connects people in new ways.

Finally, technology also connects people with work—not connection for social expression, but connection to facilitate new economic transactions that underpin new jobs.

Below, I’ll dive into each bucket and look at some of the startups building in it.

Amplify Creativity

Technology has a long history of amplifying human creativity. And humanity has a long history of lashing out against boundary-pushing technology.

In a recent interview on the Dead Cat podcast, Runway co-founder Cristóbal Valenzuela drew parallels between today’s AI breakthroughs and the creative tools of the past. Silent films, he pointed out, were rejected by Hollywood. Most famously, Charlie Chaplin refused to include dialogue in many of his films; his film Modern Times is itself a critique of the influence of technology on human life.

Critics of “The Talkies”—as talking pictures were called—asked a simple question: “What will happen to the orchestra?”

The worry was that the orchestra that played alongside silent films would be out of a job. This worry was valid, of course, but the introduction of sound into movies dramatically grew the industry, thereby increasing net employment by an order of magnitude.

This is true of many innovations: short-term pain for some (e.g., losing a job in the orchestra), long-term gain for many (e.g., new jobs created, like sound editor and sound mixer). Every change has positive and negative externalities.

Valenzuela’s company, Runway, uses AI for real-time video editing and collaboration. In some ways, you can think of Runway as photoshop on steroids, and Valenzuela also draws a comparison to the early days of photoshop. The design world roundly rejected photoshop, arguing that people wouldn’t be able to tell truth from fiction. (In some ways, this has echoes of today’s controversy around deepfakes.) Of course, photoshop has its downsides—airbrushed magazine covers no doubt made us all feel worse about our bodies—but it also ushered in a new wave of visual expression.

This week, Runway announced its new Gen-1 product, a tool that allows you to generate new videos from existing videos. You can take a video of you walking on the street, for instance, and make it claymation style. You can take a video of you skiing and transform it into the style of the moon landing. The Gen-1 demo on Twitter is stunning.

AI is just the latest wave, but technology has been consistently reinventing how humans create. Figma brought design into the browser, expanding the definition of “designer” in doing so. Veed gives its users video creation superpowers; Overwolf makes modding and building in-game apps easy; Descript allows for intuitive audio editing (it’s the software I used to edit last week’s podcast).

Better creative tools crowd in more creation. We see this with TikTok and its sister editing app, CapCut—two of 2022’s five most-downloaded apps.

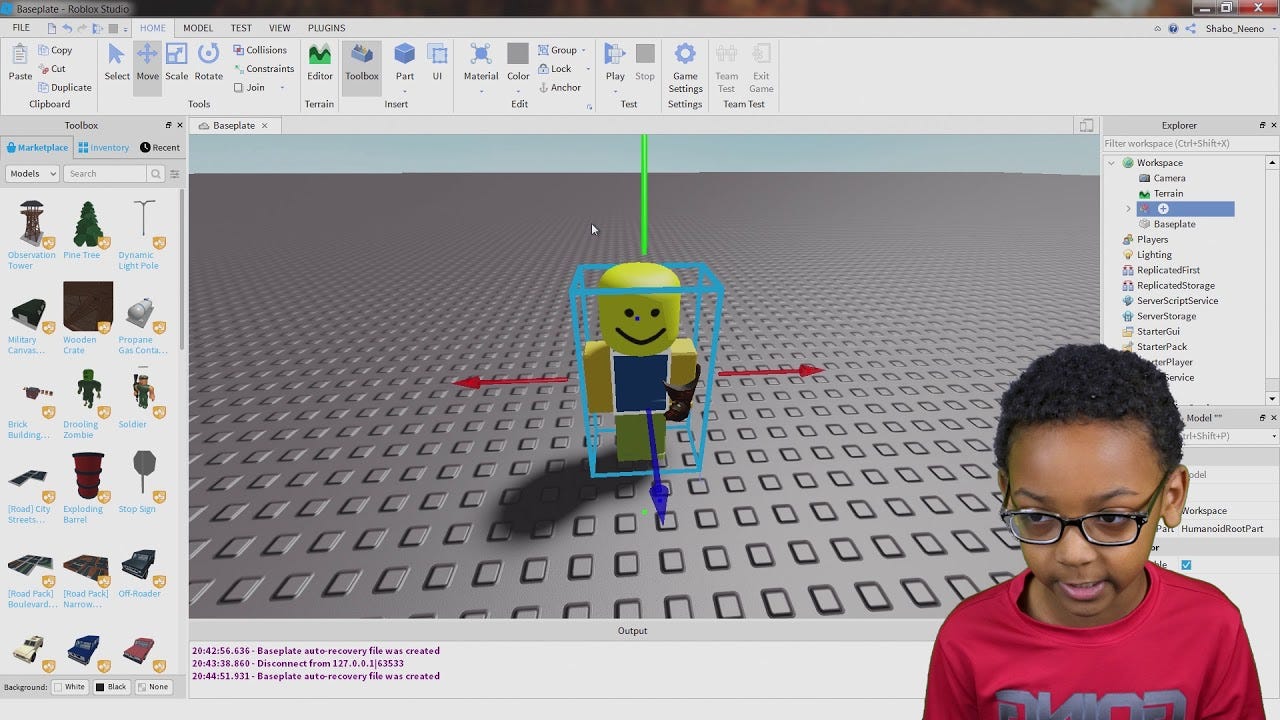

We see this in Roblox and Minecraft, which allow young kids to build complex worlds with software legos. For years, “Minecraft” was the #2 term on YouTube behind “music” as millions of people learned the ropes of in-world creation. Here’s the 10-year-old Shabo Neeno teaching others how to build with Roblox Studio on his YouTube channel. When I was his age, I could barely turn on my Nintendo 64.

And we see more creation in the professional-grade content now made with accessible tools. Oscar-winning movies like Parasite, The Social Network, and No Country for Old Man have been edited on Apple’s Final Cut Pro software—something you and I can buy for $299. Lil Nas X bought the beat for “Old Town Road” for $30 on the online marketplace BeatStars—the song went on to be the longest-running No. 1 hit in Billboard Hot 100 history, with 19 consecutive weeks on top.

The next wave will come with AI-powered creative tools like Midjourney, Runway, and Alpaca. Most are still image-focused so far, but we’ll see them extend to richer media formats like video and 3D gameworlds.

Amplify Productivity

Just as technology can give superpowers to creatives, technology can make us better and faster at our jobs. We saw this with the productivity tools of the last generation—first Microsoft Office 365, then Google Workspace, and finally the rise of product-led-growth startups like Slack, Notion, and Figma.

In an interview with Forbes last week, Bill Gates made the case for how AI will augment white-collar work, to life-changing effects:

Wearing my foundation hat [The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation], the idea that a math tutor that’s available to inner city students, or medical advice that’s available to people in Africa who during their life, generally wouldn’t ever get to see a doctor, that’s pretty fantastic. You know, we don’t have white collar worker capacity available for lots of worthy causes. I have to say, really in the last year, the progress [in AI] has gotten me quite excited.

Gates went on to list AI as the successor in a lineage of three seminal technology moments: 1) the personal computer, 2) the personal computer with a GUI (graphic user interface—essentially, what made PCs accessible to everyday people), and 3) the internet.

I’d say, this is right up there. We’ve got the PC without a graphics interface. Then you have the PC with a graphics interface, which are things like Windows and Mac…Then of course, the internet takes that to a whole new level. When I was CEO of Microsoft, I wrote the internet “tidal wave” memo. It’s pretty stunning that what I’m seeing in AI just in the last 12 months is every bit as important as the PC, the PC with GUI, or the internet. As the four most important milestones in digital technology, this ranks up there.

In prior eras, technology supercharged human productivity. The steam engine transformed mechanical work. The mechanized loom industrialized weaving. The internal combustion engine proved a lot more powerful and scalable than horses. In the most recent tech epoch, software did the trick. There are still emergent software tools making work easier and faster, many of them covered in last month’s piece Enterprise Software Is Dead. Long Live Enterprise Software. But there’s no doubt AI is the next wave. I like how Replit’s founder Amjad Massad put it in a recent podcast: AI tools collapse the distance between idea and product.

Hebbia is neural search for the enterprise—put more simply, Ctrl+F but for contextual, nuanced questions. Rewind is “The Search Engine for Your Life,” allowing you to sort through anything you’ve seen, heard, and read. Rewind began with its founder, Dan Siroker, pondering a simple question: “What if we could use technology to augment our memory the same way a hearing aid can augment our hearing?”

And ChatGPT, of course, is changing everything. The laurels continue to pile up: ChatGPT passed an MBA exam at Wharton; ChatGPT took the bar and passed; ChatGPT passed medical licensing exams.

My friend Nafez writes about how ChatGPT can now augment (and nearly replace) everything a teacher does, end-to-end:

Ask ChatGPT to create a syllabus for you on your topic of choice

Then ask it to create the script for the first lesson or two.

Modify and edit the script to make sure it’s accurate

Plug that into a tool like Synthesia.

Upload these “lectures” to your hosting platform of choice.

Voila

Two closing thoughts on how AI may impact productivity:

First, I often think about the Robert Graves quote: “There’s no such thing as good writing, only good rewriting.” Will AI replace the act of writing a first draft? Maybe we’ll all become editors, polishers who add a human flair to AI-produced text.

And second, who wins? Big Tech owns the distribution—Microsoft and Google most of all. Over a billion people use tools like Excel and Google Docs. Will the Goliaths simply add AI as a layer on top of existing tools that we already use? Will they quell upstarts in the same way that Microsoft Teams used better distribution to stall Slack’s growth? Or is AI a big enough paradigm shift that more agile companies with AI encoded in their DNA can outmaneuver the productivity giants?

Connect People

One of things I love about the internet is how it connects people. In college, I started an organization that matched LGBTQ+ mentors and mentees—effectively, a marketplace through which someone needing guidance and support (often for help coming out) could link up with someone who’d been there before and wanted to give back to the community. The organization wouldn’t have been able to grow without Instagram, yet few people think of Instagram as an “impactful” company.

The same concept extends to dating apps. I met my partner on Tinder, another company few would call impactful. Yet I can’t imagine a more life-altering experience for the better.

Thirty years ago, the concept of an online network didn’t exist. Today, billions of people connect through dozens of enormous online networks.

I often think of something Jack Conte at Patreon once said: “You may have grown up in a small town, where you were the only person out of 1,000 people with a specific interest. But there are 4.5 billion people on the internet, meaning that there are 4.5 million people who share your interest. Online, no niche is too niche.” This helps explain Discord’s 19 million weekly active servers and Reddit’s 2.8 million subreddits, each a thriving niche community.

A few years ago, I wrote about Soul, a Chinese consumer social company.

Soul is unique in how it captures the internet’s ability to connect. Soul—which describes itself as “an algorithm-driven online social playground”—asks you to take a personality test inspired by Myers-Briggs, then uses your answers to connect you to like-minded people. You interact with these people on “Planets,” each built around a shared interest 🪐

Soul is weird, yes, but it’s a fascinating example of how technology can bring people together. The company’s 2021 IPO filing (it later scrapped plans to list in the US) captured it well: “We believe the Soul virtual playground enables Soulers to freely engage with new people and share their ideas by breaking free of the constraints of offline connections.”

Connect People with Work

We connect with other people for many reasons—for love, for sex, for friendship, for belonging. The prior section focused on those social connections, human needs made easier through the internet’s network of 4.5 billion users.

But we also connect with people for more practical purposes: for transactions, typically economic in nature. Put differently: for work. Technology facilitates these connections too. This is Uber matching a driver with a passenger, LinkedIn connecting a prospective hire with a recruiter, DoorDash producing a courier for your chicken tikka masala.

Those examples mostly facilitate offline labor: the internet makes finding work easier, while the work happens in the real world. But more often, a new generation of tech companies enable digitally-native jobs.

For instance, you can be an online therapist with Headway or an online dietician with Nourish; you can teach English through Cambly or sell clothes on Whatnot. Last week, I wrote about our investment in Flagship, which is a newer example: you can be an online merchant with your own Flagship boutique.

My view is that Americans have long wanted more flexible, self-driven work. Millennials were just as fed up with the corporate ladder in 2013 as Gen Zs are in 2023. What’s different now is that there are more alternatives—more options for autonomous work, often work that doesn’t require you to leave your couch.

In 2027, America will become a freelance-majority workforce, with 86M freelancers.

Many of the most successful technology companies connect people with work in new ways. A decade ago, this was Amazon’s seller network, YouTube’s creator ecosystem, Etsy’s artisans. Now it’s new jobs like Whatnot seller. A recent profile in Elle centered on how Whatnot has transformed life for a woman named Zoreen Kabani. Kabani is a Dallas-based streamer who goes live every night at 10pm ET to sell clothes that she sources from online sales and thrift stores. In her words: “I fell in love with it right away, and now, Whatnot is my life. I treat this like my corporate job. I shop constantly—and that’s been my thing: dressing up and looking cute. It’s something my clients look for, to see what I’m wearing.”

On a typical night, Kabani streams to an audience ranging from 85 to 200 people. She says, “I always joke that I’m a loner, but when I’m on Whatnot, it doesn’t feel like I’m working. It feels more like a hangout with my besties than anything else.” In her first month on the platform, Kabani made $12,000; in her first three months, she made $50,000.

Online work has also come for knowledge workers. According to one study:

The study summarizes: “Amidst 130,000 tech layoffs, 62% of knowledge workers say they don’t feel secure committing to one employer anymore.” The study was commissioned by A.Team, a startup that matches engineering, product, and design talent to work. It’s always good to take such self-motivated studies with a grain of salt (the above freelancing chart has ties to Upwork, who is in the freelance business—same rule applies). But A.Team is an interesting example of highly-paid, highly-educated workers turning to “untraditional” ways to monetize their skills.

Final Thoughts

One of the better pieces I read in the past month was The Atlantic’s March 2023 cover story, Megan Garber’s “We’ve Lost the Plot.” A sample excerpt:

No company has placed a bigger bet on [our metaverse] future than Mark Zuckerberg’s. In October 2021, he rebranded Facebook as Meta to plant a flag in this notional landscape. For its new logo, the company redesigned the infinity symbol, all twists with no end. The choice was apt: The aspiration of the renamed company is to engineer a kind of endlessness. Why have mere users when you can have residents?

Why have mere users when you can have residents? Damn.

Garber continues her critique of our slot-machine-like digital existence:

Dwell in this environment long enough, and it becomes difficult to process the facts of the world through anything except entertainment. We’ve become so accustomed to its heightened atmosphere that the plain old real version of things starts to seem dull by comparison. A weather app recently sent me a push notification offering to tell me about “interesting storms.” I didn’t know I needed my storms to be interesting. Or consider an email I received from TurboTax. It informed me, cheerily, that “we’ve pulled together this year’s best tax moments and created your own personalized tax story.” Here was the entertainment imperative at its most absurd: Even my Form 1040 comes with a highlight reel.

These critiques are warranted: there are many, many downsides to technology. They’re also important; as a society, we should acknowledge the Black Mirror-esque dystopian elements of new innovations.

But it’s important to balance critiques with the optimistic view—the view of forward momentum, of how tech makes life better. Much of the startup and venture capital world runs on optimism; it’s hard to make bold bets while being pessimistic. I’ve always admired USV’s theses, for instance, including Thesis 3.0 that focuses on how technology can broaden access—access to knowledge, to capital, and to well-being. And I enjoyed the recent proclamation from Kirsten Green at Forerunner Ventures that “The next wave of game-changing companies will be life-changing companies.” Kirsten pointed to five categories:

Within each of these, startups are finding new ways to make life better. An entire separate piece could focus on these buckets.

The framework guiding this piece isn’t perfect, but it’s a way that I wrap my head around the good things happening with technology.

It’s a good thing that you no longer need $10,000 of specialized equipment to make something that looks great. Anyone can be creative with low-cost, accessible tools.

It’s a good thing that technology can remove many of the rote components of work, just as engines and turbines and conveyor belts did 100 years ago. We can all be more productive, with tech giving us superpowers.

It’s a good thing that we can connect with other people in new ways—that we can build rich relationships and find belonging in new communities.

And it’s a good thing that we can connect people with new forms of work—often, work that is more flexible, autonomous, and economically-rewarding.

There’s more to unpack in future pieces about technology’s optimistic side, but these are a few examples. They’re what keep me energized, clear-eyed, and motivated day in and day out.

Sources & Additional Reading

We’ve Lost the Plot | Megan Garber, The Atlantic

Black Mirror episodes: “White Christmas” and “San Junipero”

Inside Live Shopping | Andrea Cheng, Elle

Bill Gates on OpenAI | Alex Konrad, Forbes

The Next Wave of Game-Changing Companies Will Be Life-Changing | Kirsten Green, Forerunner Ventures

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: