This is a weekly newsletter about tech, media, and culture. To receive this newsletter in your inbox each week, you can subscribe here:

Hi Everyone 👋 ,

Over the coming weeks, I’m going to write about four consumer internet companies. Today, I’m writing about TikTok through a product lens—why it’s a groundbreaking product for both content consumption and content creation. In the coming weeks, I’ll write about Twitter, Instagram Shops (including a comparison to China’s Xiaohongshu), and Snap.

I’ll write these analyses every other week, interspersing them with other topics.

On to this week’s topic: TikTok.

Product Analysis: TikTok

Earlier this year, I wrote about the rise of TikTok in the U.S. That piece focused on TikTok’s cultural impact. At the time:

Doja Cat’s “Say So” was the #1 song in America after going viral on TikTok

Hype House was the center of the zeitgeist—and Hollywood, having missed the boat with YouTube, was rapidly signing young TikTok stars

15-year-old Charli D’Amelio had just become TikTok’s most-followed account

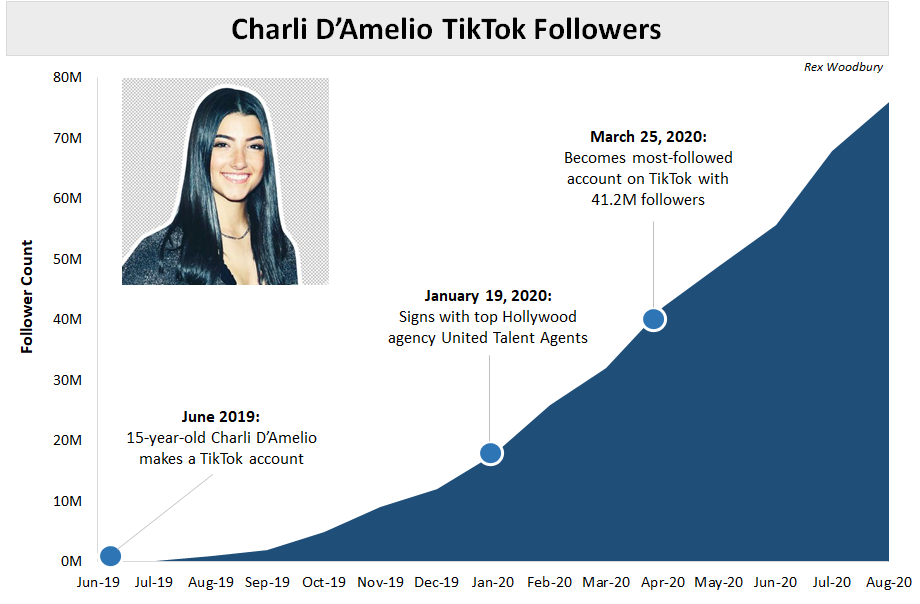

D’Amelio’s ascent is my favorite example of how quickly TikTok caught on in the U.S. On March 25, 2020, D’Amelio became the most-followed TikTok account with 41.2M followers—only 9 months after joining TikTok.

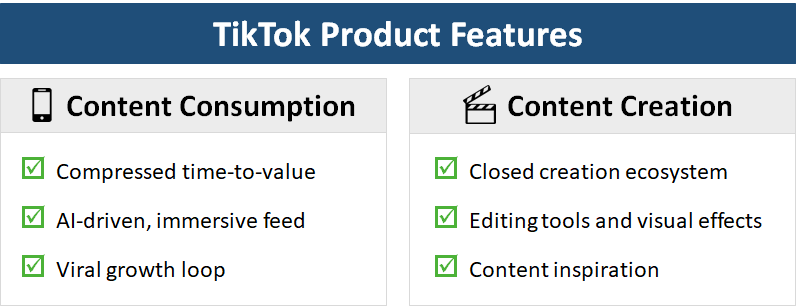

This week, I’m going to analyze TikTok as a product. TikTok gets a lot of credit for reimagining content consumption, but not enough credit for reimagining content creation. Its creation features are its more groundbreaking product innovation. (There’s a reason that the most-followed people on TikTok are called “creators” and the most-followed people on most other platforms are called “influencers”.)

TikTok removed the friction to create so effectively that 1 in 4 users create content on TikTok, compared to 1 in 1,000 on YouTube.

Whereas YouTube is a product built for consumption, TikTok is a product built for creation.

I’ll touch on both consumption and creation features, but I’ll focus on creation—even going so far as to embarrass myself by making my first-ever TikTok.

Content Consumption Features

Compressed Time-to-Value

In the early days of Facebook, Mark Zuckerberg found that new users were more likely to stick with Facebook if they made at least 10 friend connections in their first 14 days. In the early days of Twitter, Jack Dorsey noticed that user retention improved when a new user followed 30 accounts.

Time-to-value for Facebook and Twitter—the time from sign-up to realizing the value of the product—is measured in hours, days, or even weeks. It takes time for new users to understand the value of Facebook or Twitter.

TikTok’s time-to-value is measured in seconds. One of TikTok’s key features is that it requires no account sign-up. New users download the app and immediately begin consuming content; there’s no friction and there’s no learning curve. Every 15 seconds or so, the algorithm serves a new video and a new emotional high.

This isn’t a completely fair comparison, because TikTok isn’t really a social network like Facebook or Twitter—it’s a content platform more comparable to YouTube. But a new user to YouTube still needs to first select a video. Time-to-value is dramatically lower on TikTok because TikTok selects content for you.

AI-Driven, Immersive Feed

Netflix and YouTube create paralysis: users are inundated with content and overwhelmed by choice. TikTok avoids this by deciding what the user should watch with AI.

Earlier this year, TikTok revealed how its algorithm works:

The app takes into account the videos you like or share, the accounts you follow, the comments you post and the content you create to help determine your interests. In addition, the recommendation system will factor in video information like the captions, sounds, and hashtags associated with the content you like. To a lesser extent, it will also use your device and account settings information like your language preference, country setting and device type.

Other signals contribute to TikTok’s understanding of what a user likes, as well. For example, if a user watches a longer video from beginning to end, it’s considered a strong indicator of interest. This would be given a greater weight than a weaker signal, like if the viewer and poster were from the same country.

TikTok is optimized to hold your attention, serving a never-ending and constantly-refined stream of content. Because users don’t need to browse, TikTok can dedicate the entire feed to the content. Opening TikTok, this is what I see:

There are a few features on the screen—liking and commenting, for example—but most of the screen’s real estate is dedicated to the content. (As a side note: I’m very impressed by how Jason DeRulo has reinvented himself as a TikTok celebrity.)

And full-screen immersion goes hand-in-hand with audio immersion. It’s basically impossible to use TikTok in public without headphones.

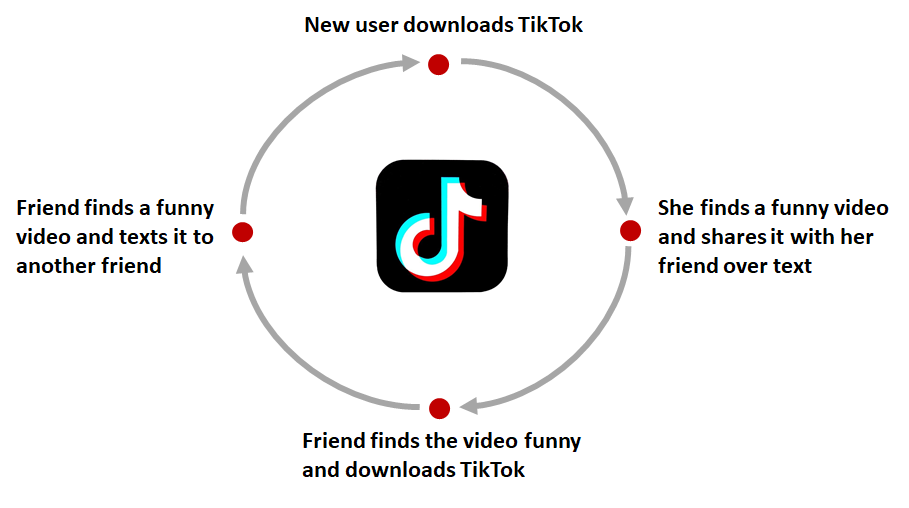

Viral Growth Loop

When sharing a post on Instagram, the default is to send a direct message within the app; Instagram keeps communication within its closed ecosystem. (The feature to share the post externally is buried under a few more taps.)

But when I go to share a post on TikTok, the first tap shows me a range of choices: SMS, Instagram, Instagram Stories, Messenger, Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp. TikTok tries to push me out of the TikTok ecosystem. This feature—making external sharing the default—creates a powerful viral loop for user growth.

The ability to share to an Instagram Story makes the above loop become one-to-many: the new user shares a TikTok to her Instagram Story and 1,000 people see it and decide to check out TikTok. TikTok has virality built into its features.

Content Creation Features

Closed Creation Ecosystem

If I visit YouTube and go to create a video, YouTube gives me no help in creating my content. I’m expected to create off-platform, stitching together Adobe Premiere, iMovie, and some fancy equipment.

TikTok, meanwhile, is a closed creation ecosystem. All I need to create high-quality content is my phone and the TikTok app.

YouTube was the first to democratize creation—anyone, in theory, could create and upload a video. But there were still barriers to creation: (1) the money to invest in expensive tools, and (2) the knowledge of how to use those tools. TikTok removed these barriers and equalized the playing field.

Editing Tools and Visual Effects

To enable its closed creation ecosystem, TikTok provides video editing tools and effects for creators. All within the app, creators can trim video clips, stitch clips together, slow down or speed up clips, and set a timer to record their videos. Vine creators used to have to blast speakers in the background to add sound to their video; on TikTok, creators play sounds through their phones while they record.

TikTok’s founder, Zhang Yiming, said that he realized early on that ordinary users didn’t have the right tools. His mission became helping the average person express themselves by making technology more accessible.

TikTok’s tools include sophisticated visual effects. I was curious how many visual effects are available on TikTok, so I went into the app and counted. There are 437 visual effects that creators can use.

Here are three of them:

With TikTok’s visual effects, I can easily “visit” Jurassic Park (left) or become a White Walker (right). (I have literally no idea what’s going on in the middle picture.)

Here’s my screen recording of some of the other effects. Check it out if you want to see me embarrassing myself some more 😁

Zhang is building what he envisioned: accessible technology that allows anyone to create. Armed with these tools, anyone can make high-quality content. And when combined with the AI-driven feed, this means that anyone can go viral if their content is deemed “good enough” by the algorithm. This is the reason that a 16-year-old like Charli D’Amelio can be the most popular person on TikTok (76.4M followers today), while traditional celebrities like Jennifer Lopez (10.7M followers) or Kylie Jenner (14.1M) lag behind. TikTok’s creation tools democratize the road to fame.

Content Inspiration

Beyond making it possible to create content, TikTok needs to make creation central to the user experience.

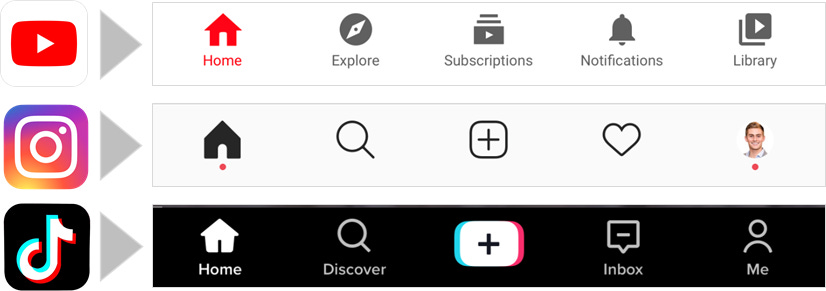

Compare the navigation bars for YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok:

YouTube’s bar is completely focused on consumption. On the YouTube app, there’s nothing that would make me think that I could or should create something. And this has an effect: it would never occur to me to share content on YouTube.

Instagram, meanwhile, puts creation front and center. In this way, TikTok is a hybrid of YouTube and Instagram: TikTok content is more complex than Instagram’s—more like a mobile-first YouTube—and yet content creation is core to the TikTok user experience like it is on Instagram.

Another hurdle to creation is deciding what to create. TikTok solves this by using sounds and challenges to provide inspiration to creators.

A new TikTok user can search by sound—often short snippets of songs—and tap “Use this sound” to create their own video set to that sound. For instance, searching “Say So” (the #1 song I mentioned earlier), shows that there are 19.9 million videos that use the song.

If a user creates a video with an original sound, that new sound becomes a sound that anyone else on TikTok can use in their content. This is a powerful driver for content generation.

Challenges work in a similar way. At any given time, there are trending challenges on TikTok that millions of users join in on. By being able to search by sounds or challenges, new creators can easily find inspiration for content.

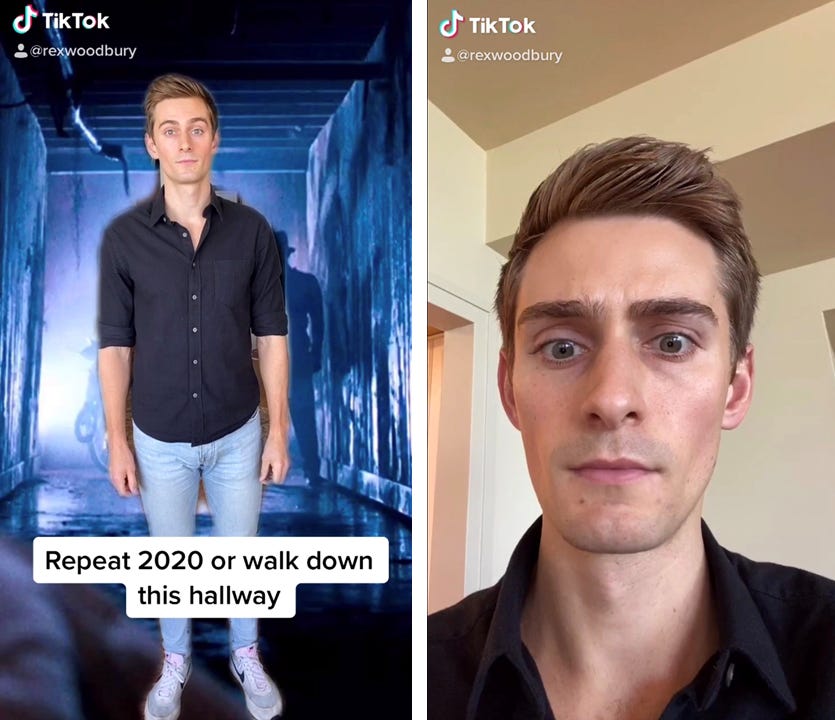

To prove this point, I decided to create my first-ever TikToks. Both are set to existing sounds, use built-in visual effects, and are popular TikTok challenges.

This video uses the green screen effect and is set to a Stevie Wonder song.

This video uses a face filter effect and is set to a sound that some user uploaded.

(Tragically, Substack doesn’t allow me to embed TikTok videos.)

It took me just a few minutes to discover these popular challenges in my feed and then to create my own versions using TikTok’s creator tools.

P.S. Combined, they have—wait for it—two likes.

Final Thoughts

In mapping out the future of work, Lightspeed’s Merci Victoria Grace wrote:

Years ago, a common refrain in tech was that Everyone is an engineer, or would be soon. People would learn to code the way they learn to read or write and it would become a basic form of communication. Lately this has evolved into the much more believable Everyone is a designer.

I would broaden this to Everyone is a creator. This is as much a trend in consumer as it is in enterprise. Just as TikTok is giving users the tools to create videos, Roblox is giving users the tools to create game worlds and Niantic is giving users the tools to create consumer AR applications.

“Low-code / no-code” isn’t the right term for this, but it’s close. Someone with no specialized knowledge can create professional-looking content by leveraging sophisticated but accessible technology. This is what’s groundbreaking about TikTok: TikTok is the most visible in a growing set of creator-focused tech platforms.

One more thought—

This is an interesting angle through which to view Microsoft’s potential acquisition of TikTok. Lots of smart people have written about why Microsoft would want to buy TikTok—Ben Thompson has a good take here—but I’ll add one more thought:

Back in 2014, Microsoft bought a 5-year-old company called Mojang for $2.5B. Mojang makes Minecraft, which has grown to ~150M MAUs and recently passed Tetris to become the best-selling game of all-time.

While Minecraft is a game creation platform and TikTok is a video creation platform, they are both Gen Z-focused platforms that give creators the tools with which to build complex content.

There are many reasons Microsoft might want TikTok. TikTok bolsters Microsoft’s advertising unit. It immediately makes Microsoft a major player in consumer social. Maybe Satya Nadella just felt left out while watching last week’s congressional hearings. But one more reason is that TikTok offers Microsoft another content platform that equips users with advanced, yet accessible tools to create.

Sources & Additional Reading—here are the pieces that inspired and informed this content; check them out for further reading on this subject:

How TikTok Holds Our Attention | Jia Tolentino | The New Yorker

Stratechery | Ben Thompson

Drinking from the Firehose | Alex Taussig | Lightspeed

The Rise of TikTok and Bytedance | Turner Novak

Thanks for reading! To receive this newsletter in your inbox weekly, subscribe here: