Fund Math for Dummies

For Most Venture Funds, the Math Ain't Mathing

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 70,000+ weekly readers by subscribing here:

Fund Math for Dummies

In recent years, elite cycling has turned into a sport of simple math.

Today’s leading cyclists—like Slovenia’s Tadej Pogacar, who just won his 4th Tour de France title on Sunday—are posting better times than champions from the doping-fueled era of Lance Armstrong and company. How can cyclists be faster today, despite the sport cracking down on PEDs?

In short, cyclists today are better at controlling the numbers.

In a good Atlantic piece this week, Matt Seaton argues that cycling really comes down to one thing: a high power-to-weight ratio, measured in watts per kilogram. Today, every leading cyclist trains and competes with a power meter fitted to their bike. This means they can precisely track their watts / kilogram output, minute by minute. During this year’s Tour de France, for example, Pogacar averaged 7 watts per kilo for 40 minutes during a critical mountain stage in the Pyrenees. Lance Armstrong, back in his heyday, had averaged just 6 watts per kilo in the same section. Experts argue that today’s cyclists go faster because they can better redline, managing their physical output with mathematical precision.

What’s the lesson here? If you want to be world-class at what you do, you’d better know the math.

Venture is no different. We’re now a mature industry, meaning we have a lot of data on fund performance. Savvy VCs should study that data and wield it to their advantage. Unfortunately, many aren’t paying attention to the math—or, just as dangerously, they’re allowing perverse incentives to convince them that the math doesn’t matter. (Spoiler alert: it does. Bad math will always catch up to you.)

The goal of this week’s piece is to dig into the math behind a venture fund.

I almost titled this piece, “Portfolio Construction for Dummies.” Then I realized that “portfolio construction” might be two words I dream about, but they probably don’t mean much to the broader startup ecosystem. So let’s call this “Fund Math for Dummies.” The goal here is a piece that’s helpful for everyone: this stuff matters for VCs, sure, but also for founders; if you’re a founder, you should understand how your VC is thinking about fund math, because incentives lie behind that math.

We’ll break this piece into four parts:

Preamble: The Venture Arrogance Score

The Only Two Things That Matter: Ownership and Outliers

Reserves and Recycling

The Case for Small Funds and Emerging Managers

Let’s dive in 👇

1) Preamble: The Venture Arrogance Score

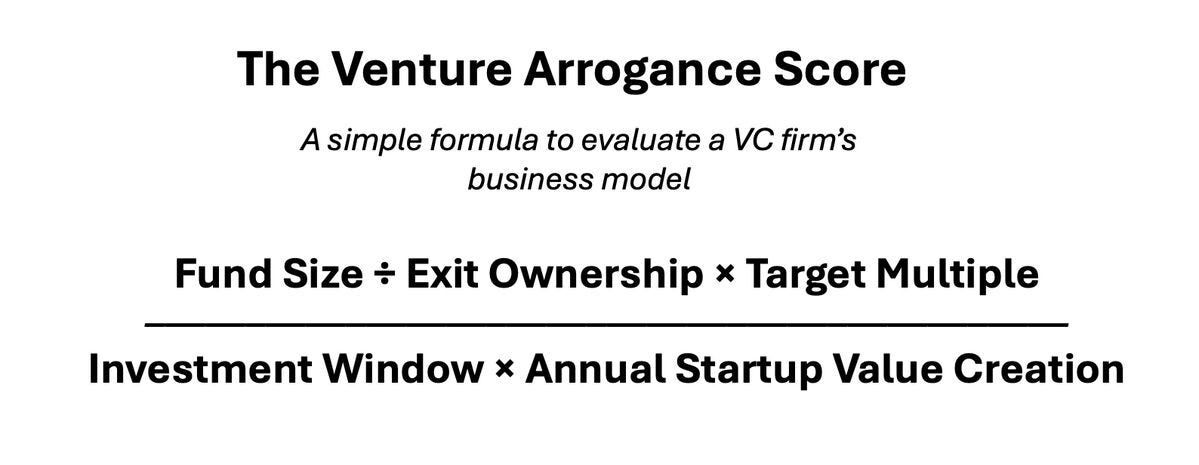

Josh Kopelman recently shared what he calls the “Venture Arrogance Score,” a formula for evaluating VC firms. The score answers the question: what percent of “total annual startup value creation” does a fund need to capture in order to generate their desired return?

Josh gives an example: let’s assume we have a $7B fund that has a 3-year investment window. The fund owns 10% of companies at exit and aims for 2.5x returns. (Note that 2.5x is a pretty low multiple for venture; we’re in growth equity / private equity territory.) The final variable is “Annual Startup Value Creation,” and PitchBook reports about $2T of total U.S. venture returns over the past decade, or about $200B / year.

Inserting our numbers into the formula, we get $175B / $600B = ~30%.

The Venture Arrogance Score is telling us that the sample firm has to capture about 30% of all value created in the startup ecosystem. That’s…really hard. As Josh concludes: “I don’t believe there has been a fund group which has repeatedly captured more than 10% of the total value created by US founders.” The math ain’t mathing.

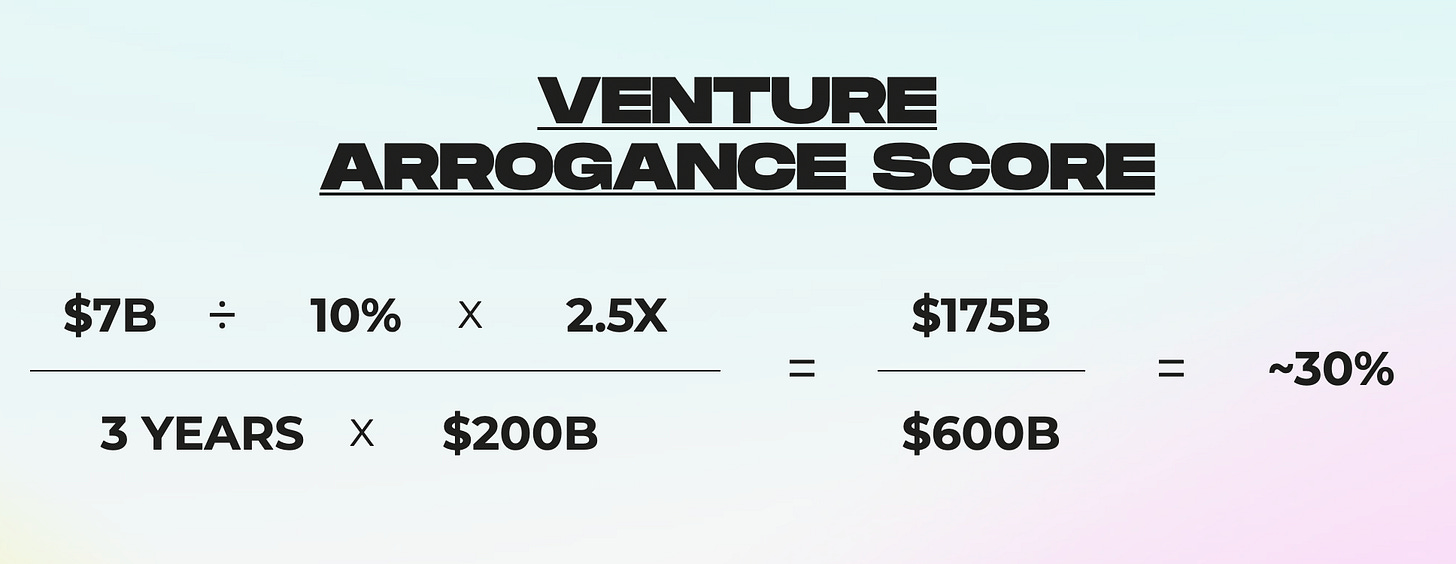

News broke in April that Andreessen Horowitz is raising a $20B (!) fund. Let’s try that math again. We’ll give a16z the benefit of the doubt, increasing exit ownership to 12.5%. We’ll also keep the 2.5x multiple.

a16z would need to capture $2 out of every $3 created by startups.

Of course, a16z would argue that outcomes will be bigger in the age of AI, which grows the denominator here. Software is eating the world, etc etc. They’re right on that. But it’s still doubtful that the returns math will work. We’re going to have a lot of disappointed LPs, LPs who thought they were seeking venture returns but ended up with PE returns. What those LPs are missing is that they’re investing in a mature asset manager branded as venture capital.

The math for big funds is tough. Insight is the third-largest shareholder in Wiz after Index and Sequoia (8% vs. 13% and 10%, respectively), meaning the firm is a huge beneficiary of Google’s $32B acquisition—the largest-ever acquisition of a venture-backed company. Yet even the $2.7B in proceeds from Wiz will return just a third of Insight’s $8B vehicle.

Two weeks back, we explained in The Taxi Cab of Venture Capital that the big venture firms are playing a different game:

Big venture firms are running the same playbook that private equity ran 15 years ago. Public PE firms include Blackstone, Apollo, TPG, and Carlyle. When you realize these firms trade as a multiple of fee-related earnings (FRE), the incentive becomes obvious: fee accumulation.

Here’s the chart of Blackstone’s fee accumulation over the past decade:

If a16z, GC, Insight, etc. have public company aspirations (and they seem to), then they’re in the business of accumulating fees. They’ll have their own versions of the Blackstone chart. These are great firms, and they’ll post good returns—I respect them greatly and don’t want to be too harsh on them. But it’s important to understand the distinction between mega-fund fund math and venture’s cottage industry roots. There’s a big gap between 10% IRRs and 40%+ IRRs.

For the rest of the venture asset class—those not accumulating assets, but chasing high cash-on-cash multiples—we need to focus on familiar math: good ownership + outlier companies = venture-scale returns.

Let’s look at the fund math for early-stage venture.

2) The Only Two Things That Matter: Ownership and Outliers

Venture capital seems complicated, but it really boils down to two things: (1) good ownership in (2) great companies. Ownership + outliers. That’s about it. Everything else will funnel into one of those two variables.

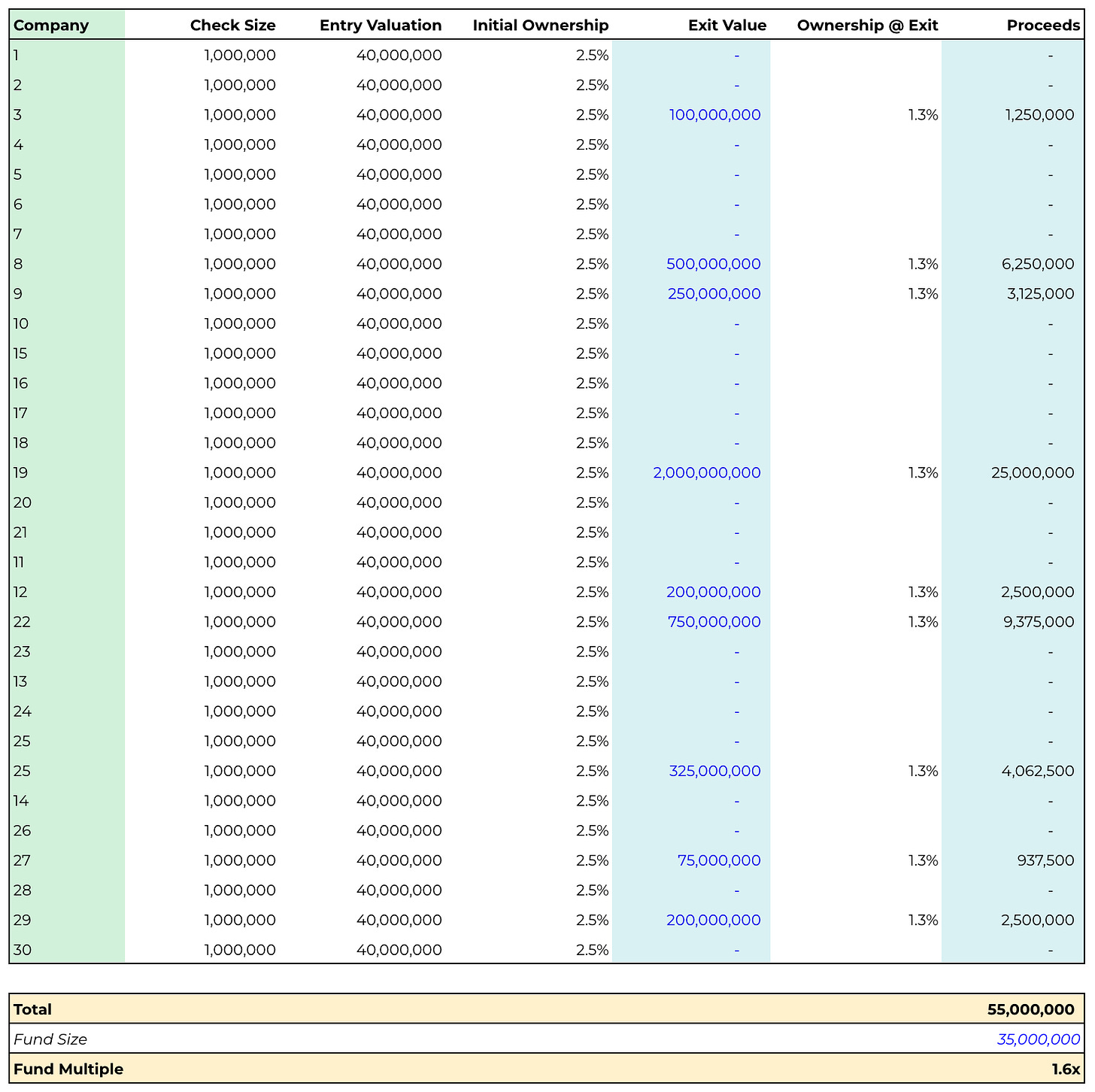

Let’s look at sample portfolio construction for a Pre-Seed firm. This is oversimplified math, but it should demonstrate the two key variables.

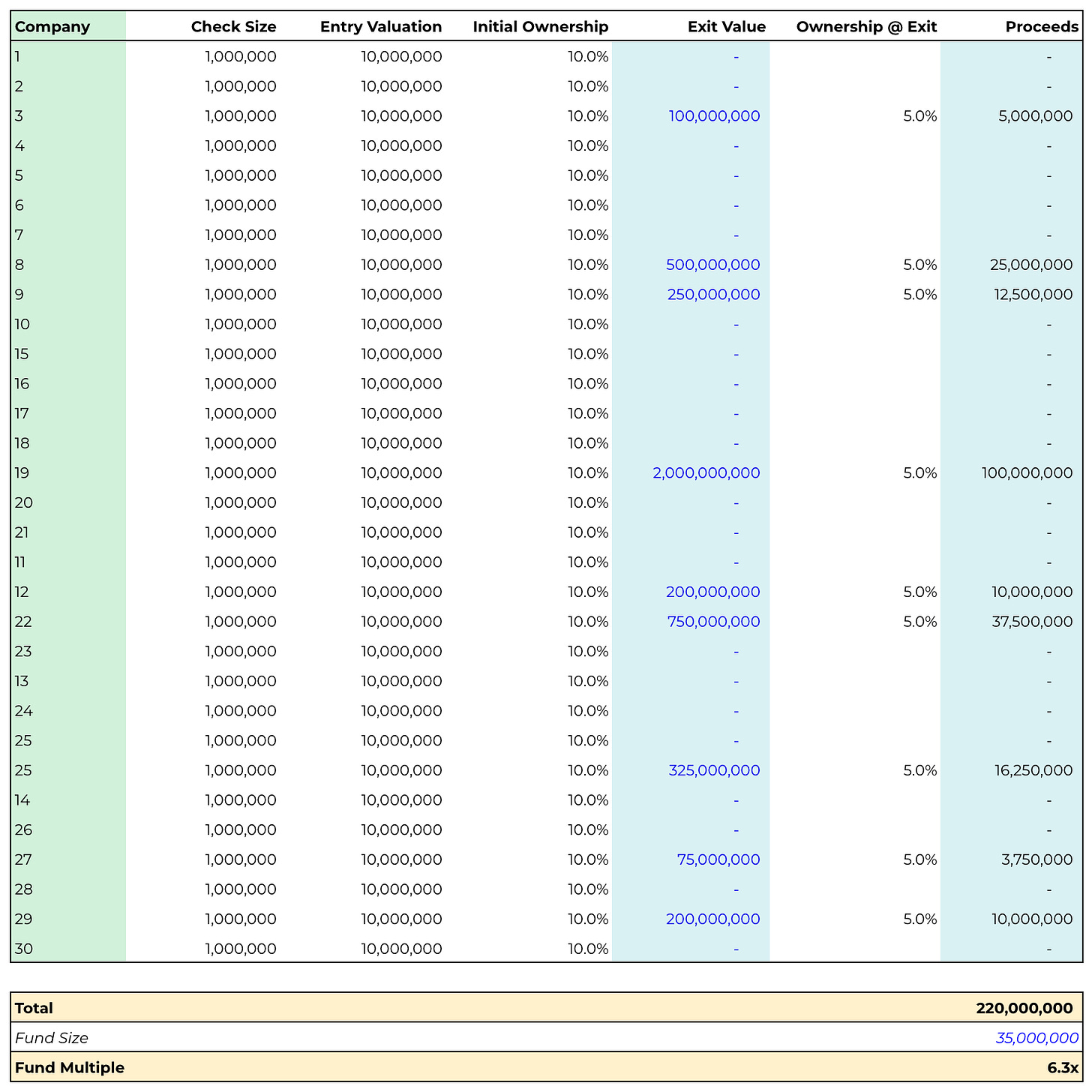

Say we invest $1M each into 30 companies. Because of fees, we’ll need a slightly-larger fund—say, $35M for simplicity. We average 10% ownership at entry ($10M post-money valuation) and get diluted 50% to 5% ownership at exit.

Here’s one set of outcomes that gets us to a ~6x multiple:

22 / 30 companies return $0, while 8 / 30 produce a range of good to great outcomes.

We’re ignoring a lot here: reserves, recycling, gross returns vs. net returns. More on some of those topics in a bit. But the math gets the point across: a handful of companies drive the lion’s share of the returns. Half the proceeds generated here come from a single company, Company 19. Remove Company 19 and you’re down from a 6.3x fund to a 3.4x fund.

A good rule of thumb in early-stage venture:

About 1/3 of companies will be zeroes.

About 1/3 of companies will return their capital, or produce modest returns.

About 1/3 of companies will be outliers, with a couple driving 90%+ of the returns.

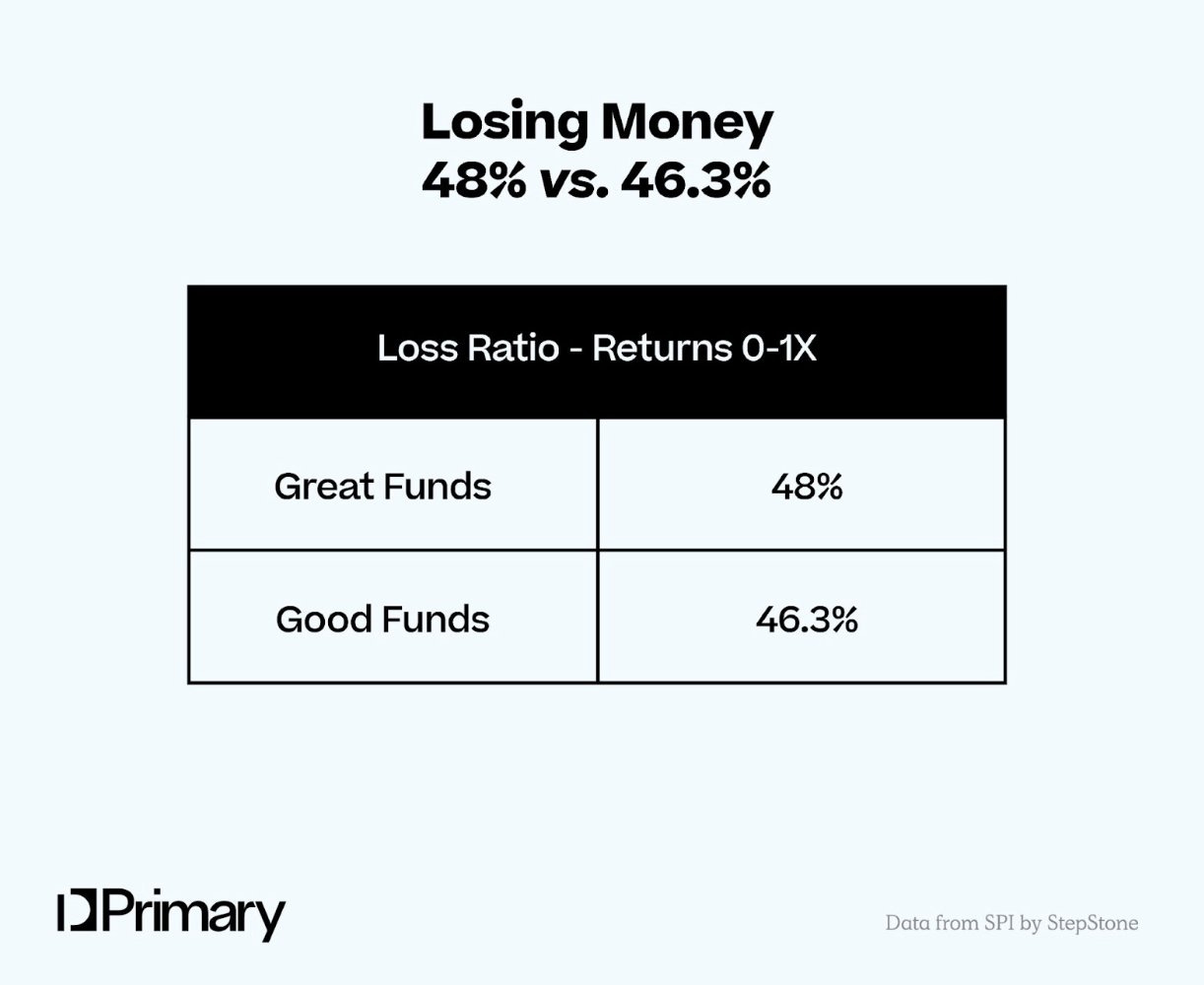

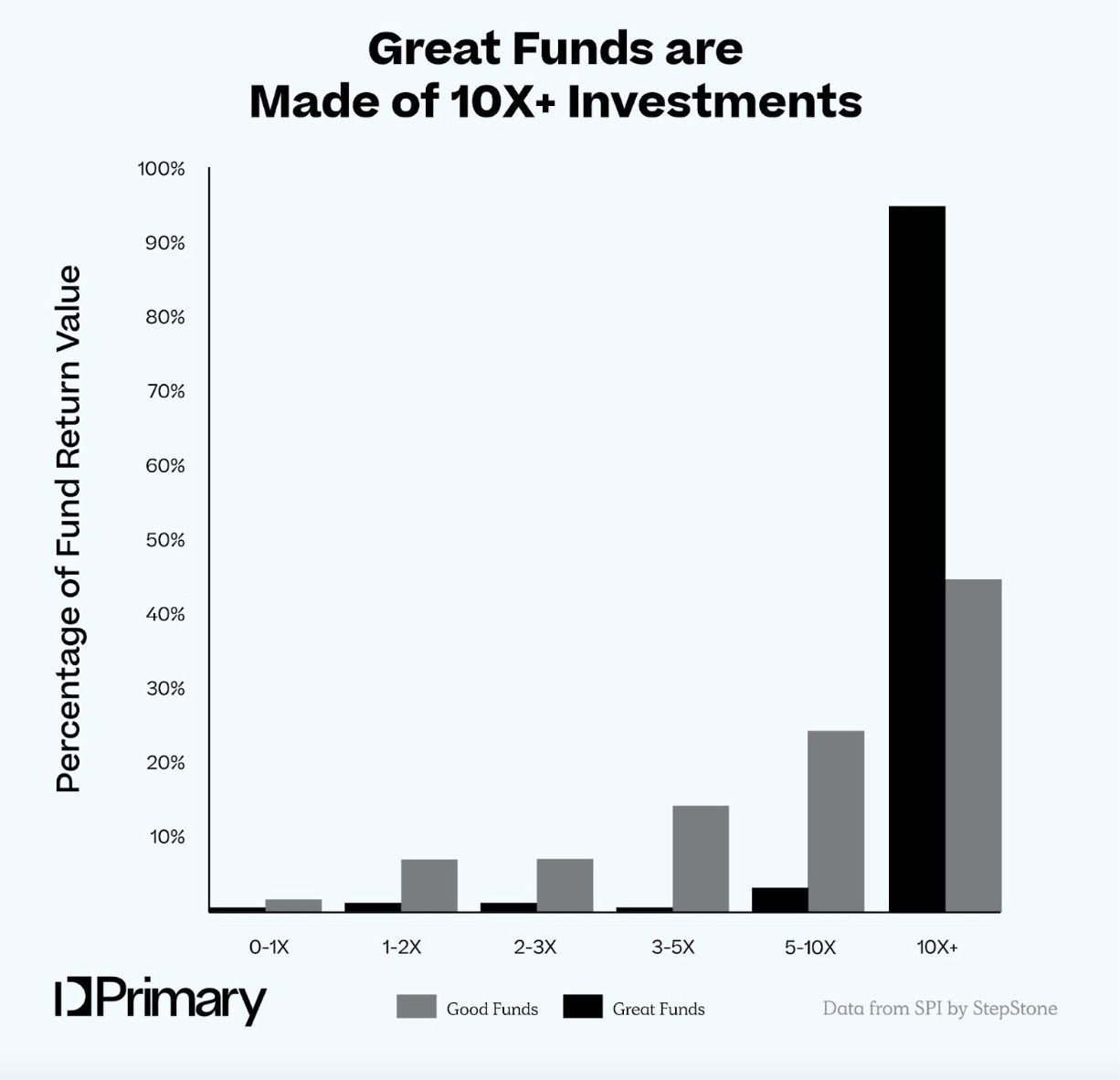

This rule of thumb, though directionally helpful, still underestimates the power law. Data from StepStone and Primary shows that we should expect a ~50% loss ratio (with “great” funds actually having higher loss ratios than “good” funds), while over 90%+ of returns come from 10x investments.

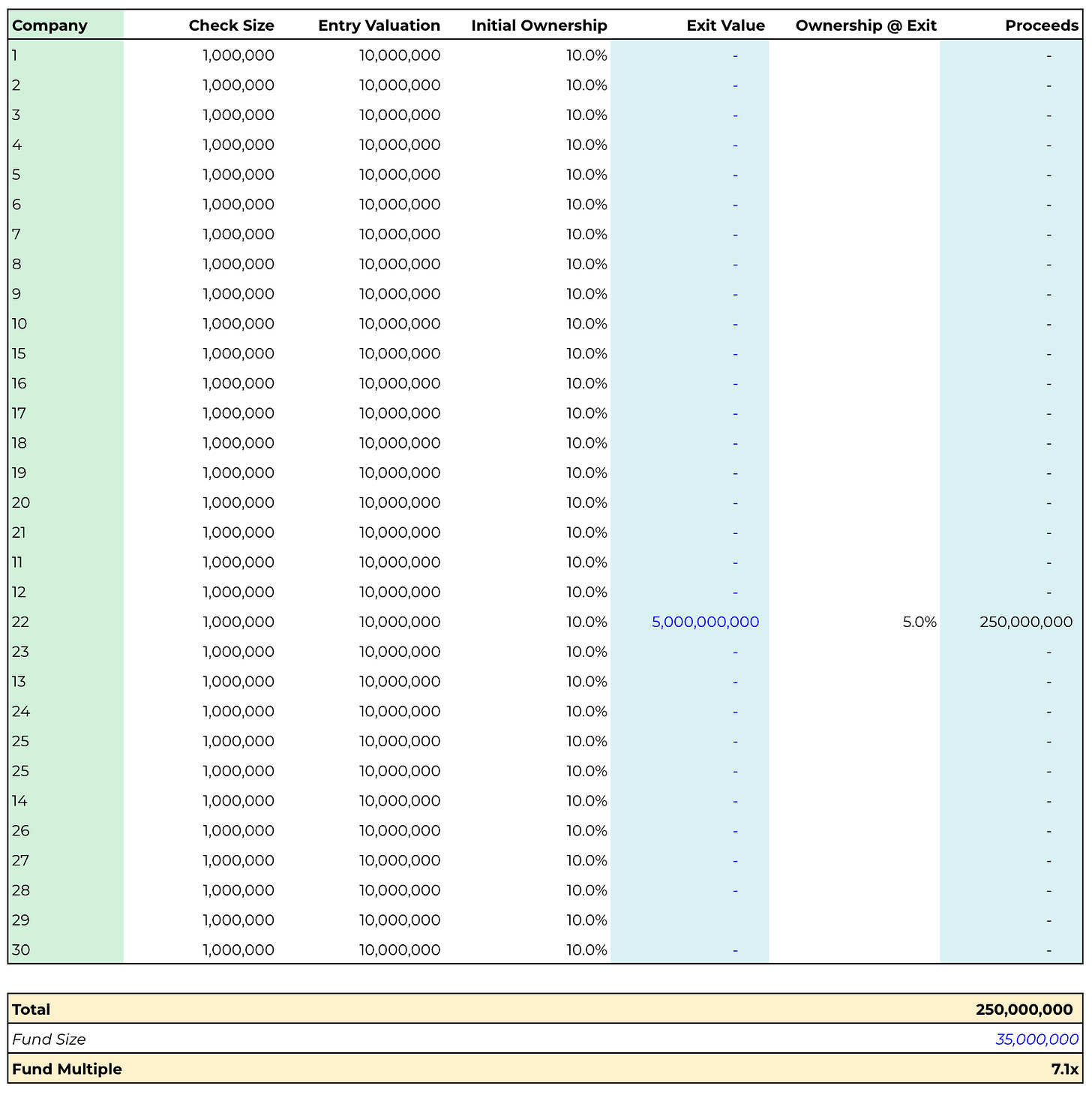

To illustrate the power law further, consider what would happen if 29 of 30 companies return $0, but one company becomes worth $5B:

Here we have a 7x fund, turning $35M into $250M+. LPs earn $172M; the GP earns $43M. All because of one company.

Sapphire Ventures put out good data on the top-performing funds in their portfolio. Of funds that are 5x or greater, the best company in the fund averaged 90x; the second-best company averaged 25x; and the average mark for the remaining was a 1x (!). Clearly, this is an industry built on outliers.

This is helpful for VCs to understand, of course: every investment should be a potential fund returner. We aren’t in the business of second base hits. But this is also helpful for founders to understand. A $100M exit might be life-changing for a founder, but it won’t move the needle for most VCs. Your VC is incentivized to have you swing for the fences. This is why venture isn’t the right path for most companies.

The second important variable, outside of outliers, is ownership.

Let’s run the same math we did in the first example, with a solid dispersion of outliers: nine of our companies product good returns, ranging from $100M to $2B outcomes. But now let’s assume that instead of entering at $10M post-money valuation and getting 10% ownership, we invest at $40M post. We get 2.5%, diluted to 1.25% by exit.

We go from a 6.3x fund to a 1.6x fund. Yikes.

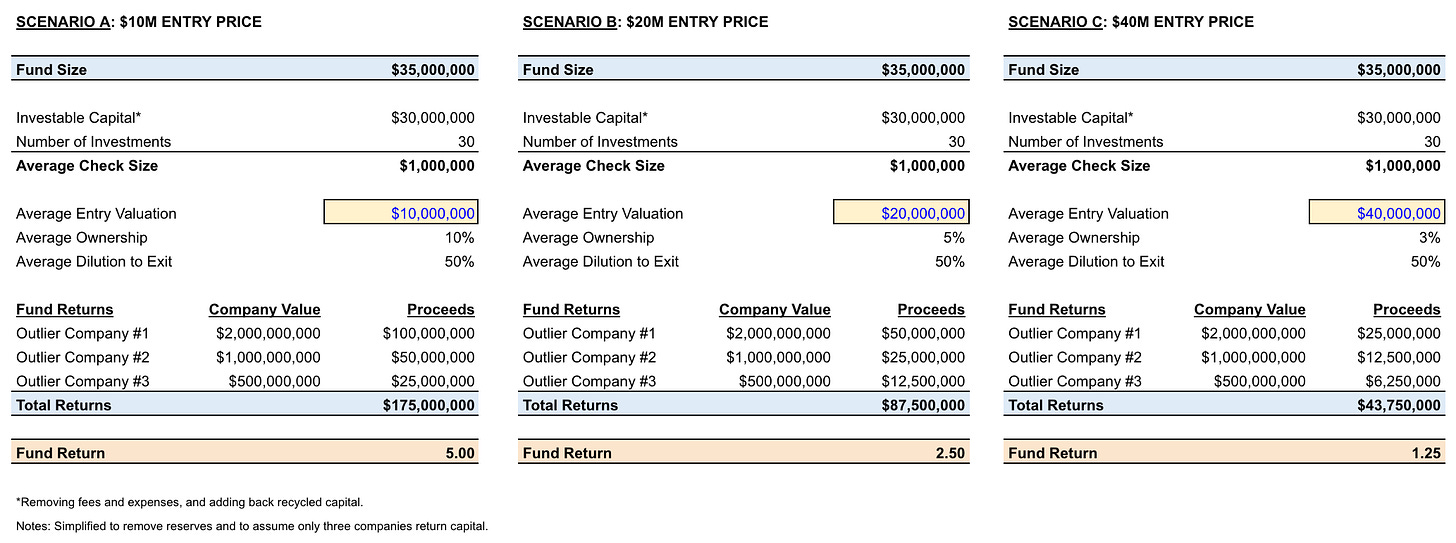

Here’s another look at why ownership is everything:

In this example, we assume our 30-company portfolio produces three outliers: a $2B company, a $1B company, and a $500M company.

In Scenario A, we averaged $10M post entry. We get a 5x fund.

In Scenario B, we averaged $20M post entry. We get a 2.5x fund.

In Scenario C, we averaged $40M post entry. We get a 1.25x fund.

This is why smaller funds are playing a different game than multi-stage firms. As a small fund, you can’t be investing in the “hot” deals at $30M, $40M, $50M and expect the math to work. My friends at multi-stage firms are playing with different math and different incentives than we are at a new fund like Daybreak. It’s fun in the near term to get into a competitive deal, but the math won’t be kind to you in the long run. You need to go early and non-consensus.

This is also why you read about Seed managers fretting about multi-stage firms moving earlier into Seed and driving up prices. The ownership math falls apart, and the entire portfolio begins to sag. High-priced Pre-Seeds and Seeds also often end up hurting the founder (sometimes even destroying the company), but that’s a topic for another day.

Let’s now talk about two variables we ignored: reserves and recycling.

3) Reserves & Recycling

The analyses above don’t take into account reserves or recycling. Both are important levers to drive returns.

Remember how we said everything funnels into ownership + outliers? Well, reserves = a way to protect your ownership. Recycling = more capital to invest in new companies (increasing the odds of getting an outlier) or to plow into best companies, protecting your ownership.

Reserves, a.k.a. pro rata, just means preserving some of your capital to follow on in your best companies. The mistake that managers make when modeling their fund: we all assume that we’re going to be putting our reserves into the winners. After all, we’re brilliant pickers, right? But often, we pile more money into companies, and then those companies still go to zero. The hit rate on follow-on should be higher, but we’re still not batting 100%.

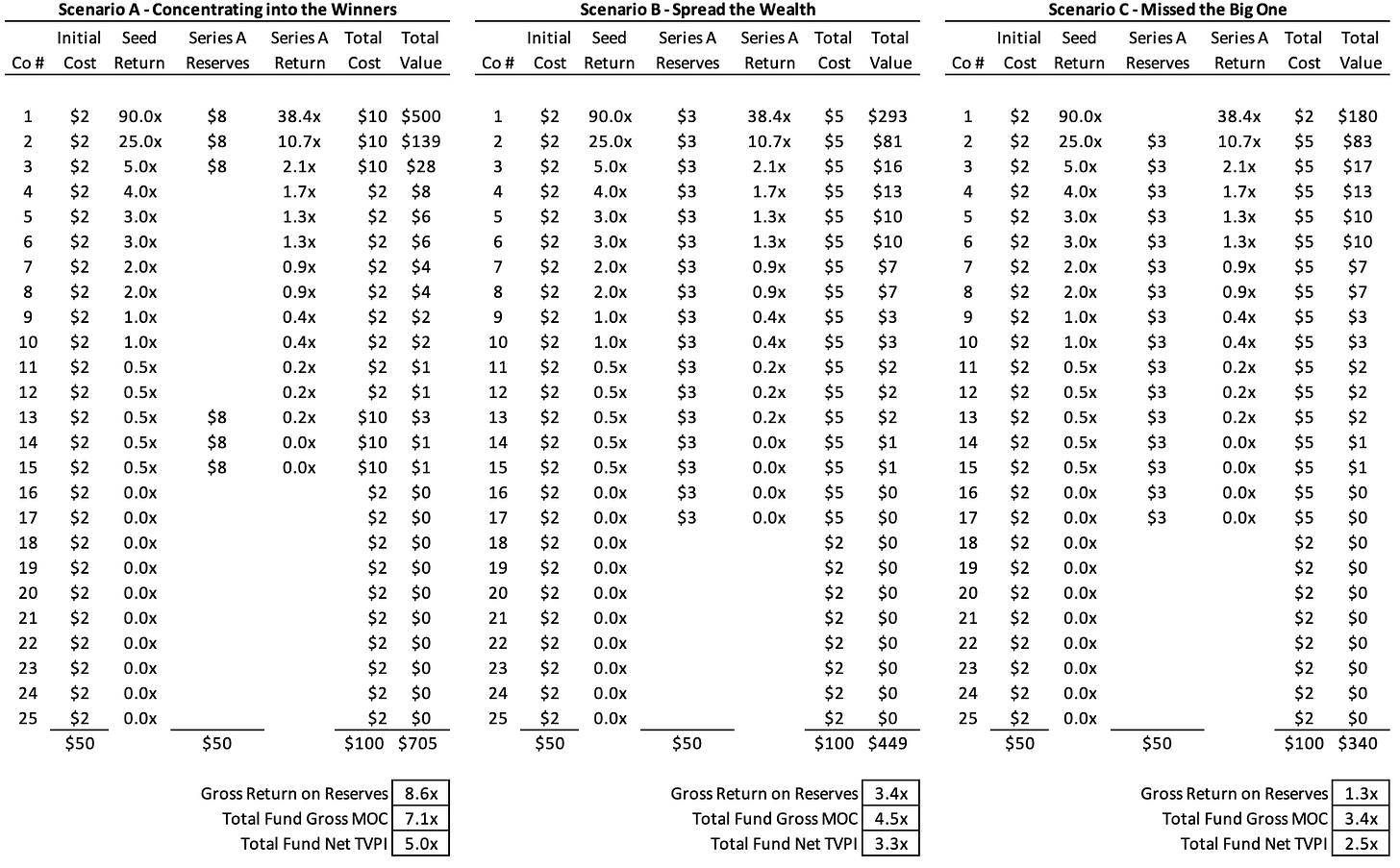

Some of the best writing on reserves math I’ve come across comes from Sapphire. Sapphire outlines three scenarios:

In Scenario A, the fund manager identifies outliers early and deploys half of reserves into the three strongest-performing companies. The other 50% of reserve dollars don’t pan out. Follow-on investments generate 8.6x, which boosts the fund’s gross multiple from 5.5x to 7.1x.

In Scenario B, the fund manager puts the same dollar amount into every company that goes on to raise a Series A (17 out of 25 Seed investments). This yields 3.4x blended on reserves, and actually hurts the fund multiple: we go from 5.5x to 4.5x gross and 4.0x to 3.3x net.

In Scenario C, the fund manager really messes up. They follow the same strategy as Scenario B, but miss the outlier company—returns plummet from 5.5x to 3.4x gross and 4.0x to 2.5x net.

You can see how reserves are critical to get right; you have to back your winners, or you drag down returns. It’s worth reading the full Sapphire piece for more detail.

One more note: for smaller funds, there’s an argument to be made for a no-reserves strategy. If follow-on prices are high, or if rounds are happening in quick succession, it might be better to deploy more first-check capital; this gives you more “shots on goal” to allow for the power law to work. For example, you might get 30 companies in the portfolio vs. 25, increasing the odds of having an outlier. In this methodology, you accept that you’ll be diluted on your ownership.

Recycling is another lever to pull to boost returns. A typical fund won’t be able to invest the full fund size, because of fees. For instance, the example earlier centered on a $35M fund putting $30M to work in investable capital. But say in year 4, one of your companies exits for a modest sum. You get $7M back—not a great return, but not nothing. Instead of returning that to LPs, the manager could invest that money, either in de novo investments or in follow-on rounds to existing companies.

Now, the GP has been able to put $37M to work—106% of the fund size. Some of the best firms in history are consistently investing over 100% of their fund, even 120%+, through smart recycling. This is a lever that’s less talked about, but that can be a powerful mechanism for driving another turn or two in your fund multiple.

4) The Case for Small Funds and Emerging Managers

Let’s end by looking at how venture performance varies by fund size. Yes, this is the self-serving part: with Daybreak, we’re building a new venture firm. That means we’re a so-called “emerging manager,” and some of the numbers here make emerging managers look pretty good. But the data doesn’t lie 🤷♂️

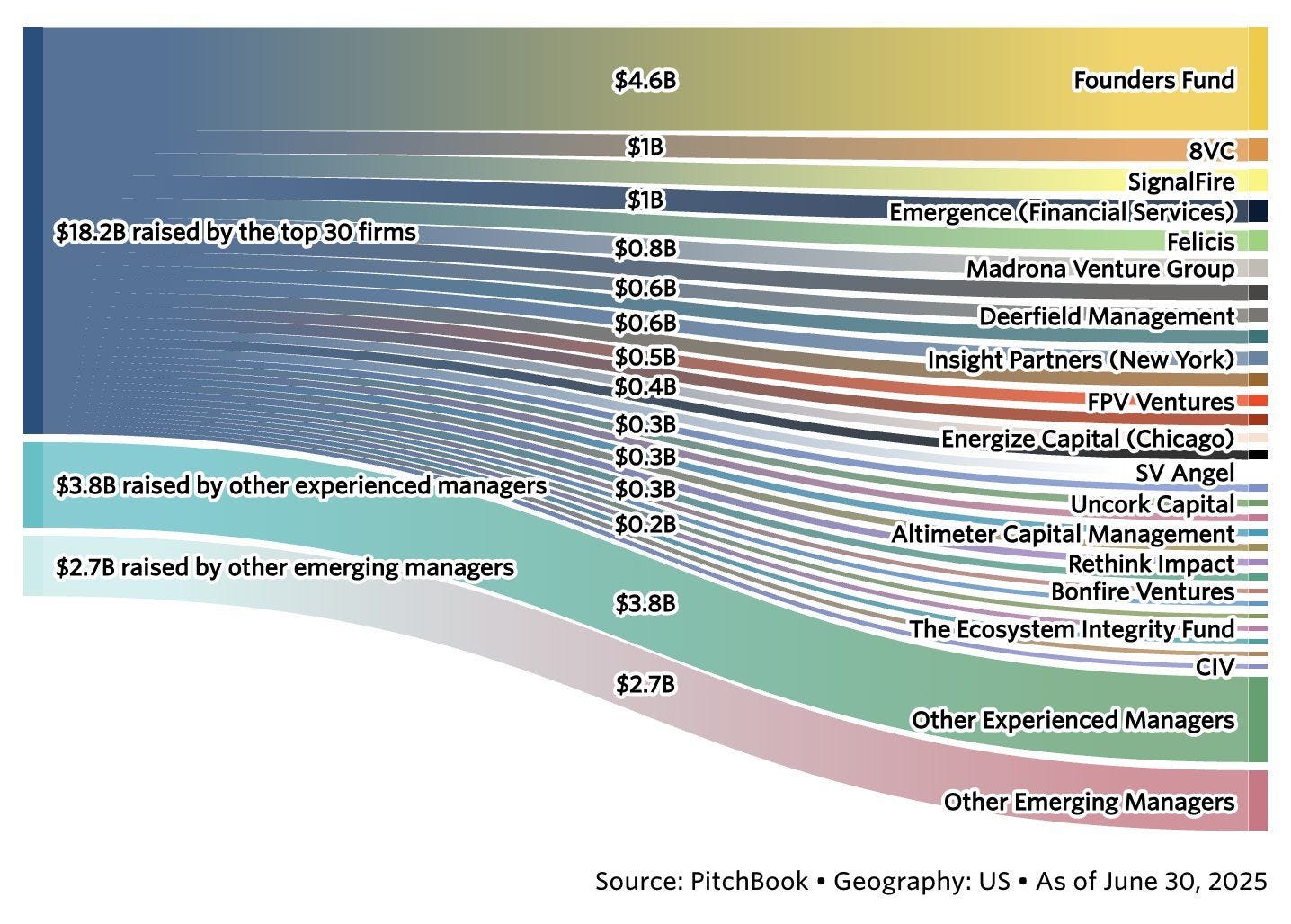

To set the scene (insert Star Wars opening crawl): venture capital has never been so consensus. In the midst of the 2022 market correction, as the post-ZIRP era took hold, the industry saw a flight to safety. VCs backed consensus winners. LPs, facing a tech downturn paired with AI-driven uncertainty, backed familiar names.

Last year, 74% of LP dollars went to the top 30 venture firms:

In the first half of this year, 50%+ of LP dollars have gone to just 12 firms:

As the adage goes, “No one ever got fired for allocating to [insert your proven multi-stage firm].”

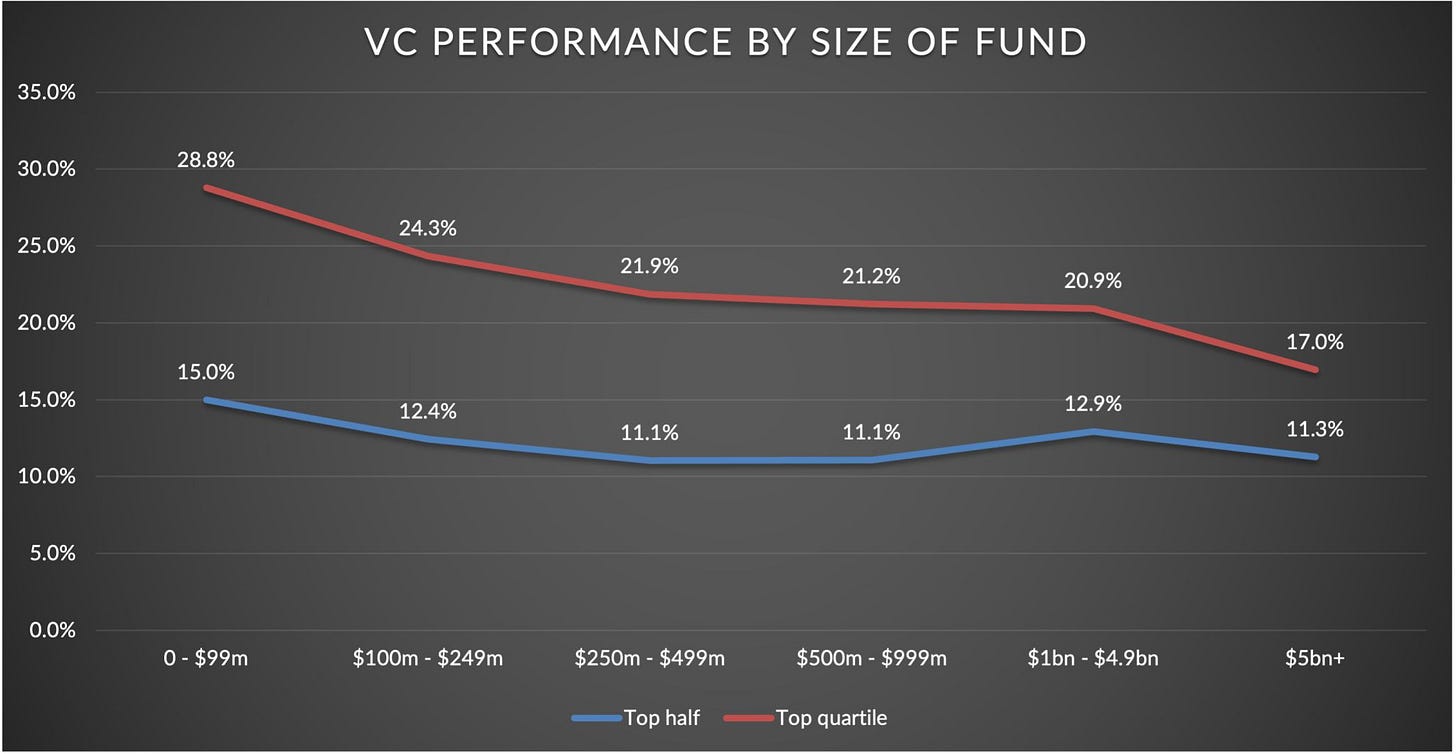

Yet this “flight to safety” actually runs against the historical data on fund performance. James Sedgwick-Heath from Dara5 shares some of the best consistent analyses on returns math for venture as an asset class. Here’s one view, based on PitchBook data, that shows how IRR decreases as fund sizes get larger:

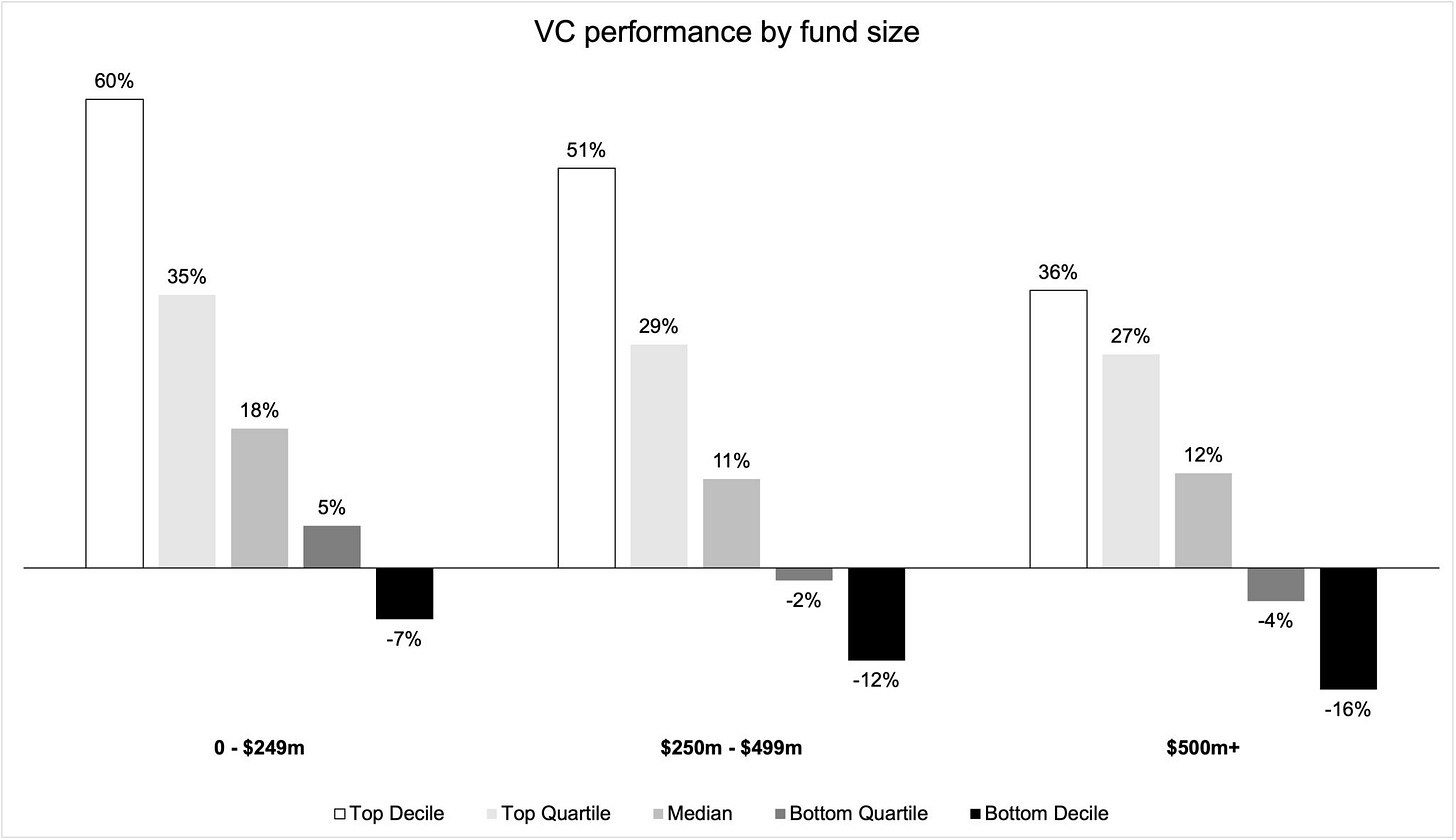

Here’s another view, showing top decile, top quartile, median, bottom quartile, and bottom decile. Top decile for <$250M funds = 60% IRRs. Top decile for $500M+ = 36% IRRs.

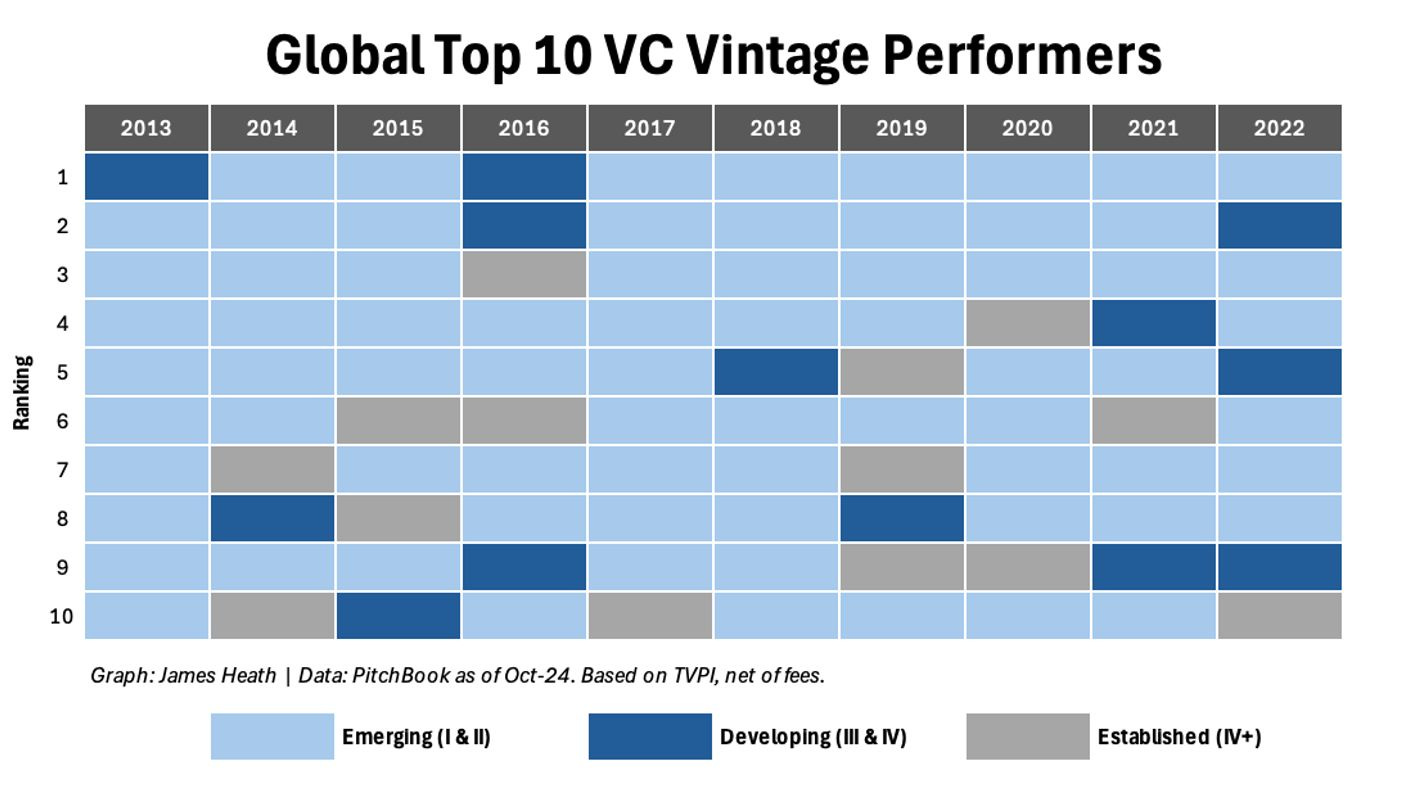

Here’s an impressive stat, from James: more than half (55%) of top decile VCs in the last ten years are Fund Is. 73% are Fund Is or Fund IIs.

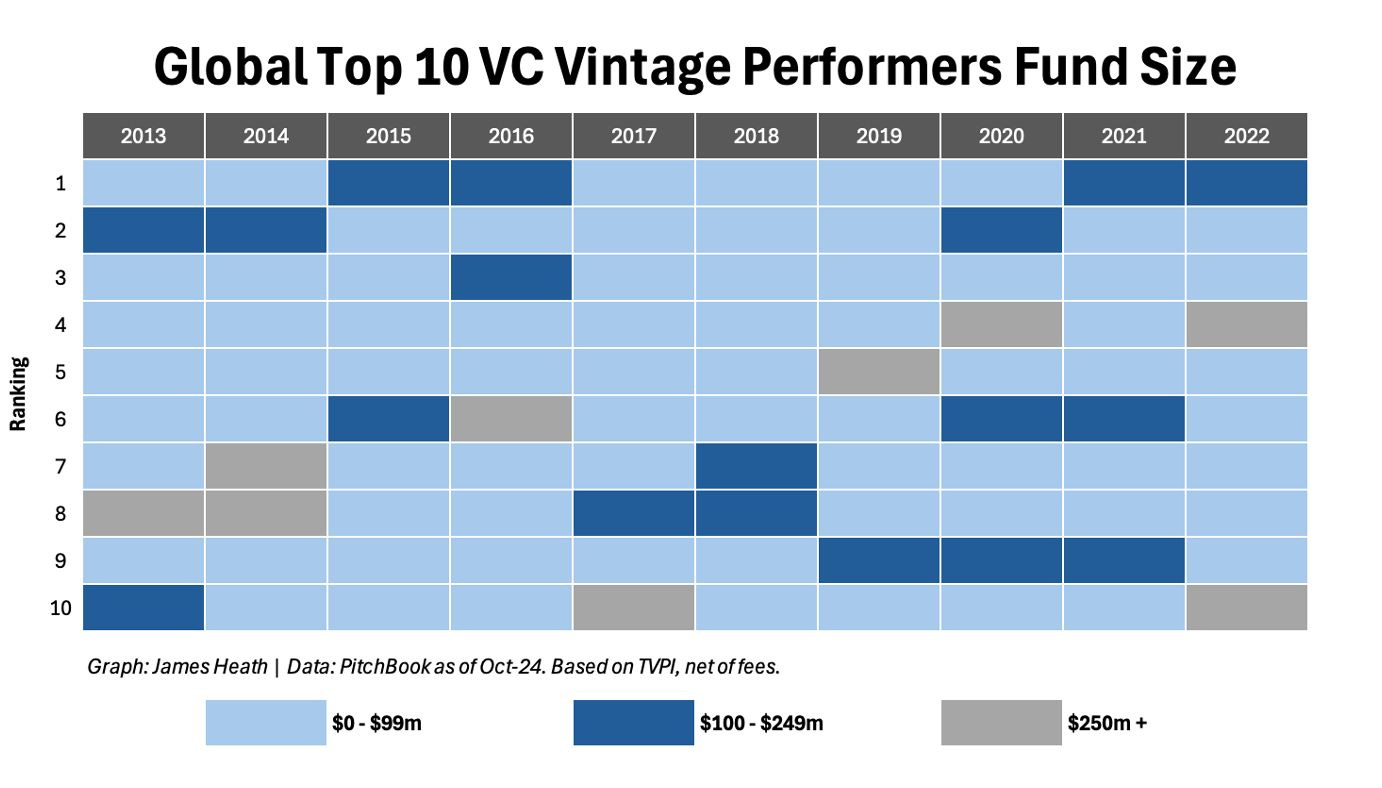

Over the past 10 years, 91% of the best-performing VC funds have been under $250M in size; 73% are under $100M.

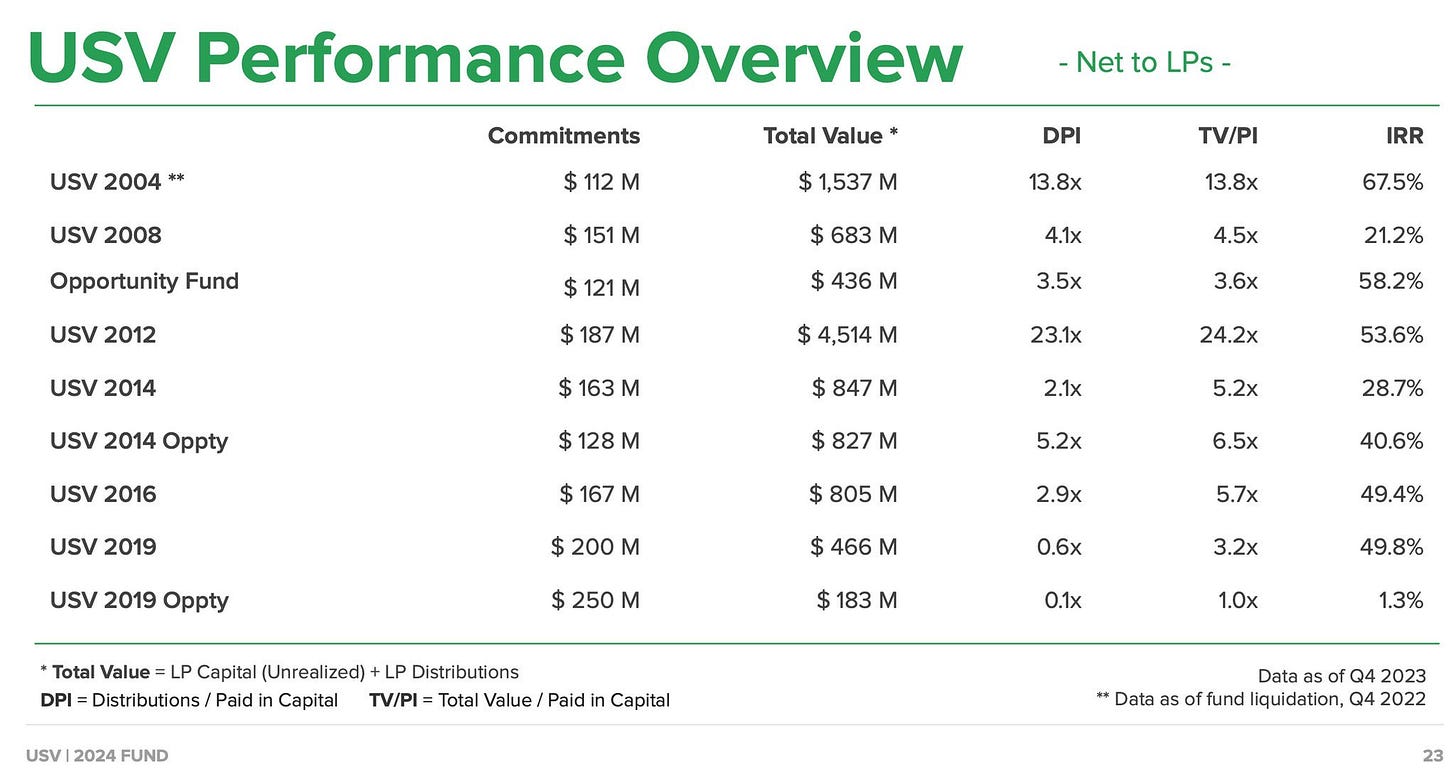

Part of this is the law of large numbers. If you’re hoping for a 23.1x fund like Union Square Ventures’s 2012 vintage, you probably need to be a sub-$250M fund.

But the reasons go beyond multiples math. I like how James puts it: “[There are] reasons are both qualitative (grit, no plan B, point to prove) and quantitative (smaller fund sizes). This is where LP/GP alignment is closest. Back the funds working for the 20, not the 2.”

Yes, there are way too many venture firms out there. Most shouldn’t exist. The ZIRP boom years, in particular, brought too many tourists into fund management—hobbyists, who see running a fund as a side hustle. The market is correcting for that excess now.

Venture has the highest returns dispersion of any asset class, but when done right, the math can be very, very good.

Final Thoughts

At some point, private equity (which encompasses everything from venture through pre-IPO rounds) becomes about putting hard dollars to work. If you put $1B into OpenAI at $300B and it becomes a $1T company, you just generated $2B in gains. That’s a lot more than you’ll generate in most Seed-stage venture funds. The saying goes, “You can’t eat IRR for lunch.” If you’re a pension fund, you probably need those major dollars at work. But for most LPs, they’re still looking for venture-like returns.

Dollar-maximizing investing is very different from “traditional” VC. It’s important to appreciate the difference. Most VC—at least old-school VC—is about generating high multiples on invested capital. The fund math works differently for General Catalyst than for First Round, for Insight than for Homebrew.

It’s important for VCs to understand the math for their fund and to trust it. Neglect ownership at your own peril. And it’s important for founders to understand the math for the funds on their cap table—to understand what’s going on behind the scenes, the portfolio machinations on ownership and reserves and recycling and so on.

Venture seems like a lot of hype and bubbles and hot rounds and FOMO. Yes, this is a people industry. But at the end of the day, it’s also just math.

Sources & Additional Reading

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: