Tech's Blind Spots: The Startups Building for Underserved Markets

From Baby Boomers to Gen Alphas, Industrial Workers to Internet Labor

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 55,000+ weekly readers by subscribing here:

Tech's Blind Spots: The Startups Building for Underserved Markets

One thing about Silicon Valley is that Silicon Valley disproportionately builds for….well, for Silicon Valley.

This means that we end up with a lot of sales automation and sales optimization software, a lot of project management dashboards, a lot of developer tools. This makes sense; people tend to build things for themselves. And it isn’t a bad thing—all of these products make life easier and better. They’re also attractive candidates for venture funding: high-margin SaaS, repeatable go-to-markets, often mission-critical products. Any balanced portfolio should have a number of these companies.

But Silicon Valley’s inwardness also means that other groups get overlooked by technology. Those groups underpin large opportunities themselves, ones not yet captured by startups. This week’s piece looks at four such groups. Two groups are overlooked demographics, and two groups are overlooked segments of workers:

Baby Boomers

Gen Alphas

Industrials, Manufacturing, & Agriculture Workers

Internet Workers

Let’s dive in.

Baby Boomers

In one of the first Digital Native pieces (3.5 years ago!), I wrote about how America’s population is rapidly aging, yet few startups are building for seniors. Both of those facts remain true.

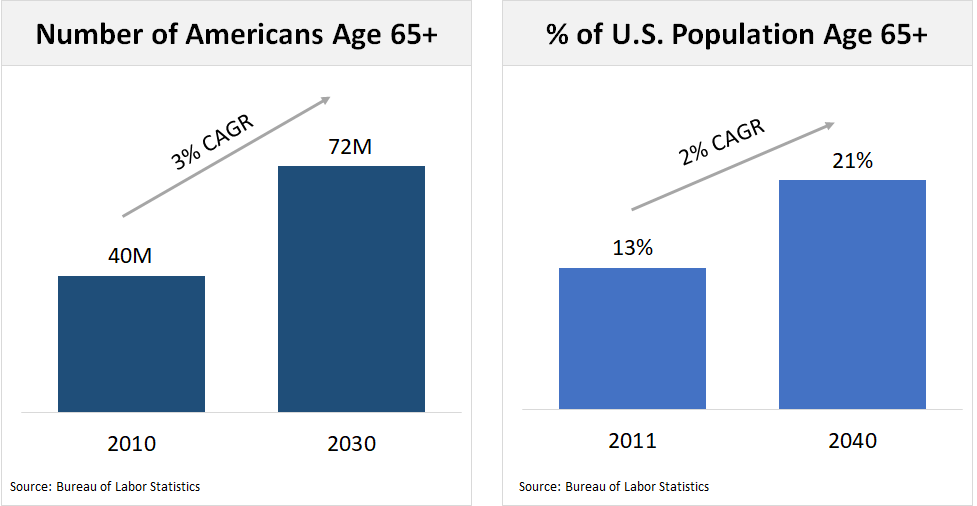

Back then, I somehow found the time to turn raw data into pretty PowerPoint charts, so here are a few charts that outline this demographic shift:

We’re on track for more than one in five Americans to be a senior citizen by 2040. (Half the country is already over 50.) And this is a global phenomenon: people 65 and older will soon outnumber children under 5 for the first time in history.

Every day, 10,000 more Americans turn 65, and there are already more Baby Boomers in the U.S. than there are people in the U.K., Israel, and Switzerland combined.

Boomers are also digital adopters. A few stats (some a few years out-of-date):

90% own a computer

70% own a smartphone

53% are on Facebook

Boomers comprise 33% of all internet users

Boomers spend $7B a year on online shopping

30M consider themselves “heavy internet users”

And Boomers make up 40% of wireless customers

Digital adoption coincides with another important fact: Boomers are a huge swath of the economy. Boomers are the wealthiest generation in history, collectively earning double that of the “Silent Generation” above them. They control 70% of the country’s disposable income and 50% of consumer spending dollars.

Yet just ~5% of advertising dollars target Boomers:

Compared to Millennials—who are targeted by 50% of ad dollars—Boomers have 15x the net worth, 2x the median income, and 50% higher average monthly household spend.

We see a similar story play out in the startup world: few companies are building for seniors, despite the so-called “silver tsunami” heading our way. My view is that this will soon change. Seniors have been an overlooked market, but they can (and will) be the foundation for large businesses.

Take home care. According to the AARP, 87% of older Americans want to age in their homes. “Home health and personal care aide” is the fastest-growing field in America this decade. The visualization below tracks the fastest-growing jobs for the 2030s, and home health aide is the big blue bubble on the left:

That’s a helluva bubble.

One business idea: vertical SaaS for home health, or for senior care centers. At Index, we partnered with a company in the U.K. called Birdie doing just this. Using Birdie’s software, a care manager can log daily tasks for their care recipient—administering medication, for example—while also abstracting away administrative complexities (invoicing, scheduling, auditing).

Or what about a platform that lets home health aides launch their own senior care practices? This combines two major shifts: 1) an aging population, and 2) the growth in autonomous, self-directed labor. I expect many of the home health aides in the blue bubble above will be self-employed. Who facilitates discovery through a marketplace matching caregiver and care recipient, and who builds the software to run the caregiving business?

An aging population also means worsening health. By 2027, U.S. health expenditures will reach $6 trillion (about 20% of GDP), driven primarily by our aging population. Every year, 3.7M more Americans become eligible for Medicare, with average healthcare costs 5x those of children and 3x those of working-age people.

Ripple effects are coming; everything from cancer screening to diabetes management will need to be overhauled.

A final opportunity: addressing the senior loneliness epidemic. A 2018 study found that a quarter of people over 65 are considered socially isolated; a 2012 study found that 43% of people over 60 report feeling lonely. That was before a global pandemic dramatically worsened isolation, particularly for older Americans. (This has derivative effects on health. Loneliness is associated with higher rates of heart disease and stroke and a 50% increased risk of dementia.)

Over the past year, I’ve met a number of companies building for seniors. Some are building AI companions to assist with daily utility-oriented tasks; others are building AI companions for entertainment and companionship. Some are building software for adult children to use to help their aging parents, while others are building software for professional caretakers.

The challenges lie in the details. Go-to-market motions are tough for older people; they’re not your typical savvy tech adopters. Many startups have to nail distribution through another channel—the health aide, for instance, or the Boomer’s adult child. Products built for older Americans also tend to be vitamins, not painkillers. In other words, they’re “nice to have’s” but not always essential.

Yet these challenges are surmountable with the right product, business model, and go-to-market. The tailwinds and willingness to pay (and ability to pay) are all there. The devil’s in the details of executing the right playbook.

Gen Alphas

While Baby Boomers are digital adopters, today’s kids are digital natives. (Hey, that’s the name of this publication!) A 2017 Common Sense Media report found that among U.S. 0- to 8-year-olds, nearly all have access to a smartphone in the home and nearly half have their own tablet. Here’s a nifty chart from that old Digital Native piece, made by yours truly:

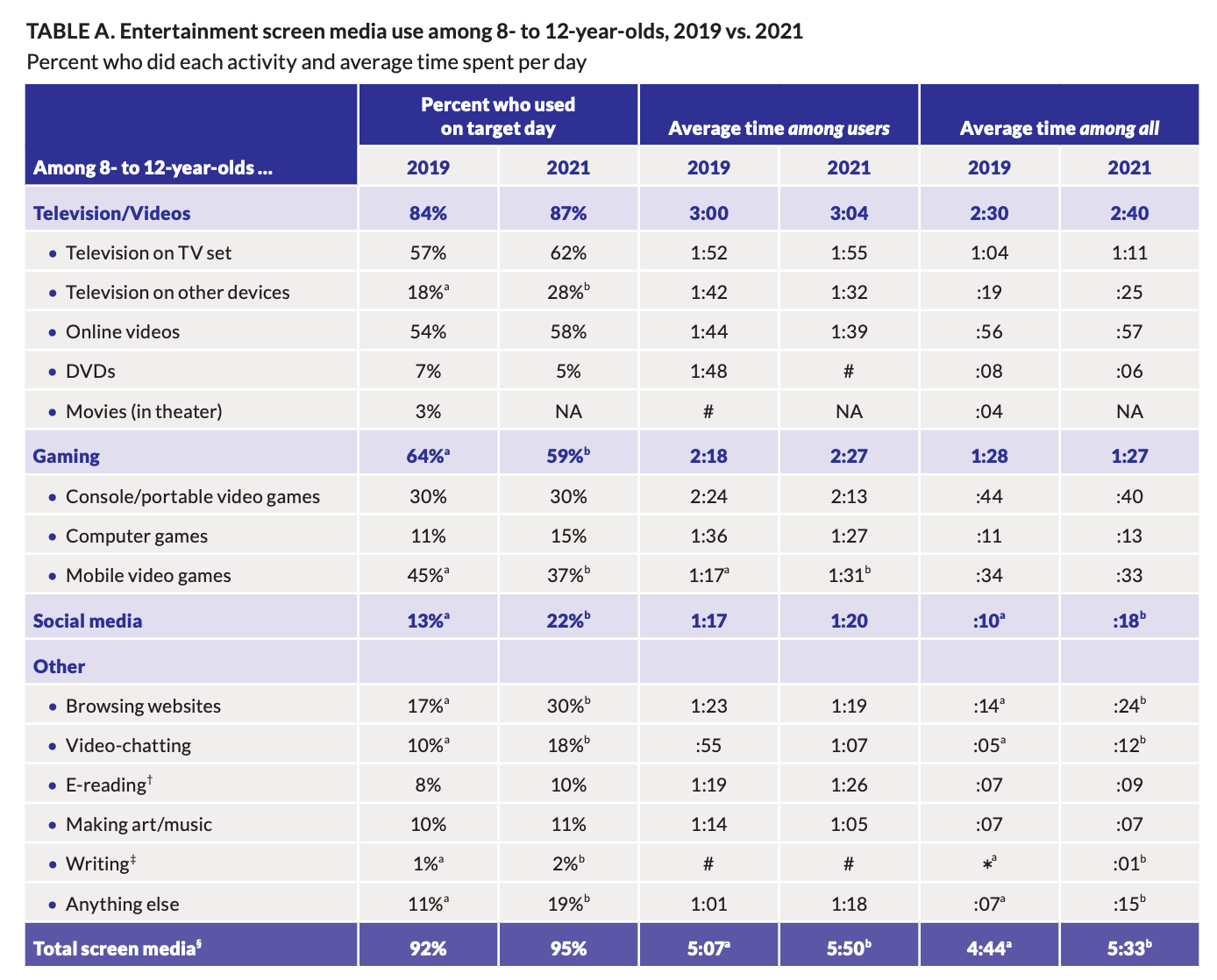

A search for more recent data turns up Common Sense Media’s 2023 Report, but the report focuses more on the 8-12 demographic. This demo captures the oldest among Gen Alphas—the first of Gen Alpha were born in 2010, and the last will be born this year:

Clearly, technology use remains on the rise. A more granular view shows jumps in online video consumption, internet browsing, and video chatting:

How should companies build for Gen Alpha?

I’ve seen a few “Roblox for a younger demo” companies, and there’s probably a business to be built around learning + socialization for young kids. Most Roblox users are clustered in the tween and teen years, with only 22% under 9, leaving a gap for digitally-savvy younger kids.

I imagine Apple’s forthcoming Vision Pro will also have applications targeting young users, and recent reports note a partnership with Disney+. But I have a hard time seeing Gen Alpha as early adopters of a bulky, high-priced headset.

AI + Gen Alpha is also an interesting intersection.

One interesting application of AI comes from the startup MiniStudio, which uses AI to turn children’s drawings into rich visual works. Driveway chalk drawings or scratch paper sketches become beautiful works of art.

What other ways can AI amplify child creativity?

One of the more unusual—and interesting—early-stage companies is Curio, which makes AI-powered plushies for kids that can hold entire conversions. It’s like M3GAN, but without the sinister persona and rampant murder.

Curio launched in December, and I can see Curio working more than I can see a physical AI product like Humane’s pin working.

The challenge that technology companies building for Gen Alphas will face is tech backlash. A frequent topic in Digital Native is the rise of nostalgia, which has its roots in a rejection of our screen-obsessed modern world. Earlier this week, this post blew up on Twitter:

There’s a risk that tech products built for younger users will have to contend with parental backlash to tech adoption at such an early age. Yet while many parents would profess to wanting to limit technology for the kids, the Common Sense Media data above shows a different story. I imagine there will be large technology businesses built to serve Gen Alphas.

Industrials, Manufacturing, & Agriculture Labor

A lot of startups build for knowledge workers—particularly for knowledge workers in tech fields: product managers, designers, engineers.

Other forms of skilled labor—particularly those involving physical labor—often get overlooked. This comes at a time when skilled trades are on the rise. A recent survey from Thumbtack (so take it with a grain of salt) found that 73% of Gen Zs say they respect skilled trade as a career, putting it second only to medicine (77%); 47% were interested in pursuing a career in a trade. One potential reason: 74% say they believe skilled trade jobs won’t be replaced by AI.

Skilled trade programs are seeing sizable increases in enrollment:

We’ve seen successful vertical SaaS companies build for trades. ServiceTitan, for instance, offers all-in-one software for home and commercial contractors and has ridden that space past $500M+ ARR.

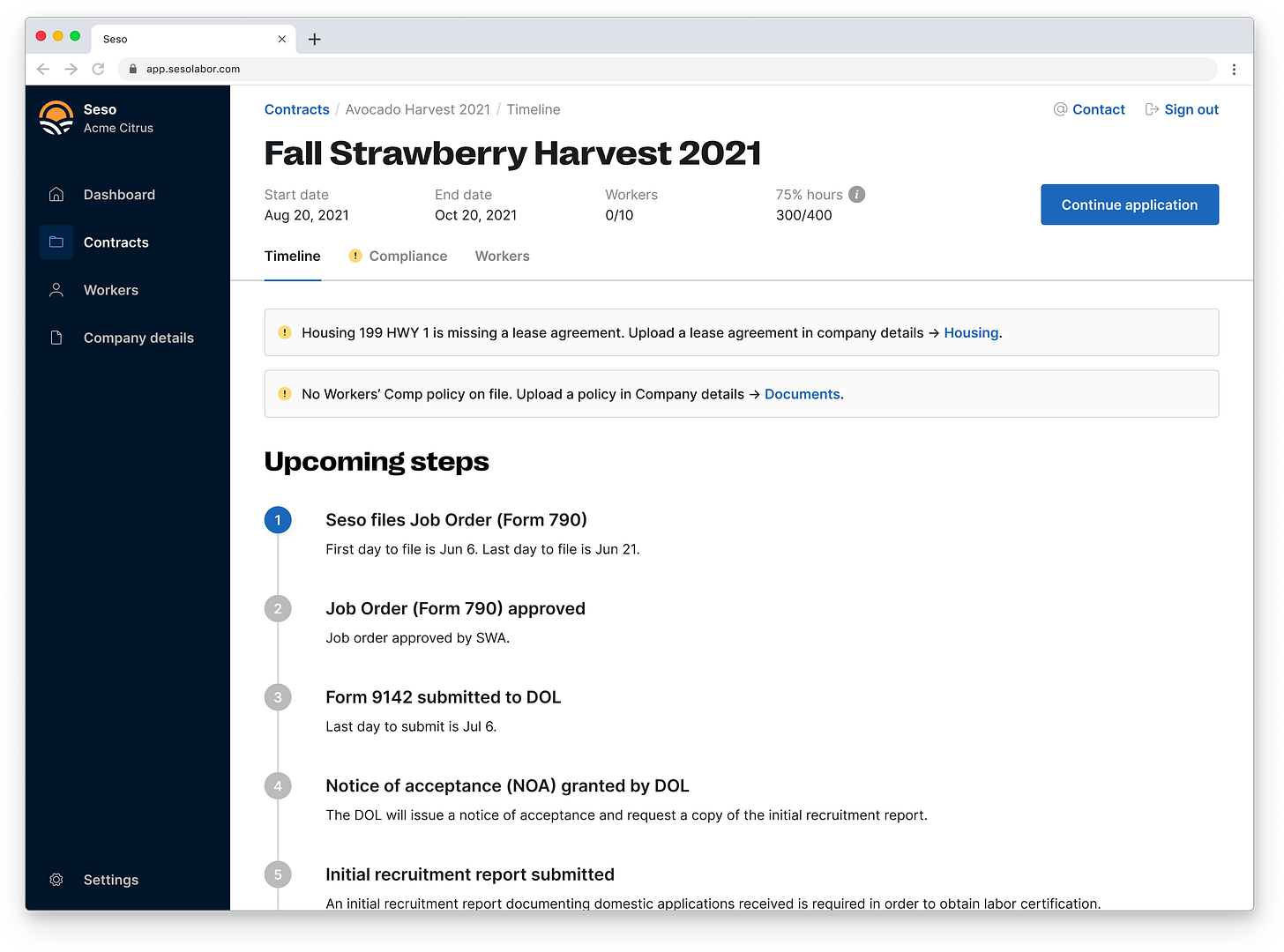

But there are many more sets of workers to build for, and startups are finding clever ways to build for overlooked groups. Seso, for instance, is vertical SaaS built for agricultural workers. The company’s wedge in is managing the H-2A visa process, a process by which farms can legally bring migrant workers into the country for seasonal farm labor.

Traba is another example, offering light-industrial staffing—think workers at warehouses and distribution centers. Traba smartly started by nailing one geo, Miami, and is now expanding to new geos.

Businesses building for workers like these—workers outside of desk work / knowledge work—exist across the sliding scale between vertical SaaS companies and labor marketplaces. Different verticals have different levels of attractiveness for startups, with nuances around frequency of work (meaning repeat use of the marketplace and the resulting importance of discovery), stickiness, and the type of work (1099 vs. salaried worker, for instance).

But what these companies have in common: Silicon Valley isn’t typically building for your farmer or warehouse worker. When you talk to customers of these products, it’s clear that they’re not used to elegant software or tailored workflows; building a product 10x better than the current offering (which often involves pen-and-paper and bulletin boards) is an accessible task, and companies can then layer on more products to become the central hub through which these workers and their companies manage labor.

Internet Workers

Small- to medium-sized businesses are America’s backbone: according to the U.S. Small Business Association, there are 33M SMBs in the U.S. employing 62M Americans, about 46% of all private sector employees.

Some of the best startups of the last decade were built for SMBs. You’d be hard-pressed to go into any SMB in America and not find a Square point-of-sale iPad, for instance. Square started with Jim McKelvey’s realization that he should be able to accept an AmEx payment for his glassblowing business, something a small merchant like him couldn’t do at the time. It’s since grown to 4M sellers and a $40B market cap.

The next generation of small businesses, in my mind, are internet-native businesses.

These are the digitally-native, often solopreneur businesses I’ve written about in the past—the Amazon sellers and Etsy sellers, the YouTube creators and TikTok creators, the Headway teletherapists and Flagship merchants.

To take one memorable, unusual example: consider the rise of the OnlyFans creator. OnlyFans has a reported 3M creators, some of whom are earning a living wage through their paywalled content. Those creators tap into 220M registered users, who pay subscriptions and micropayments to unlock content (typically NSFW content).

Sex sells, and OnlyFans rode the pandemic, the destigmatization of sex work, and a clever business model to enormous success. By April 2020, OnlyFans was being name-dropped by Beyonce on Megan Thee Stallion’s “Savage.”

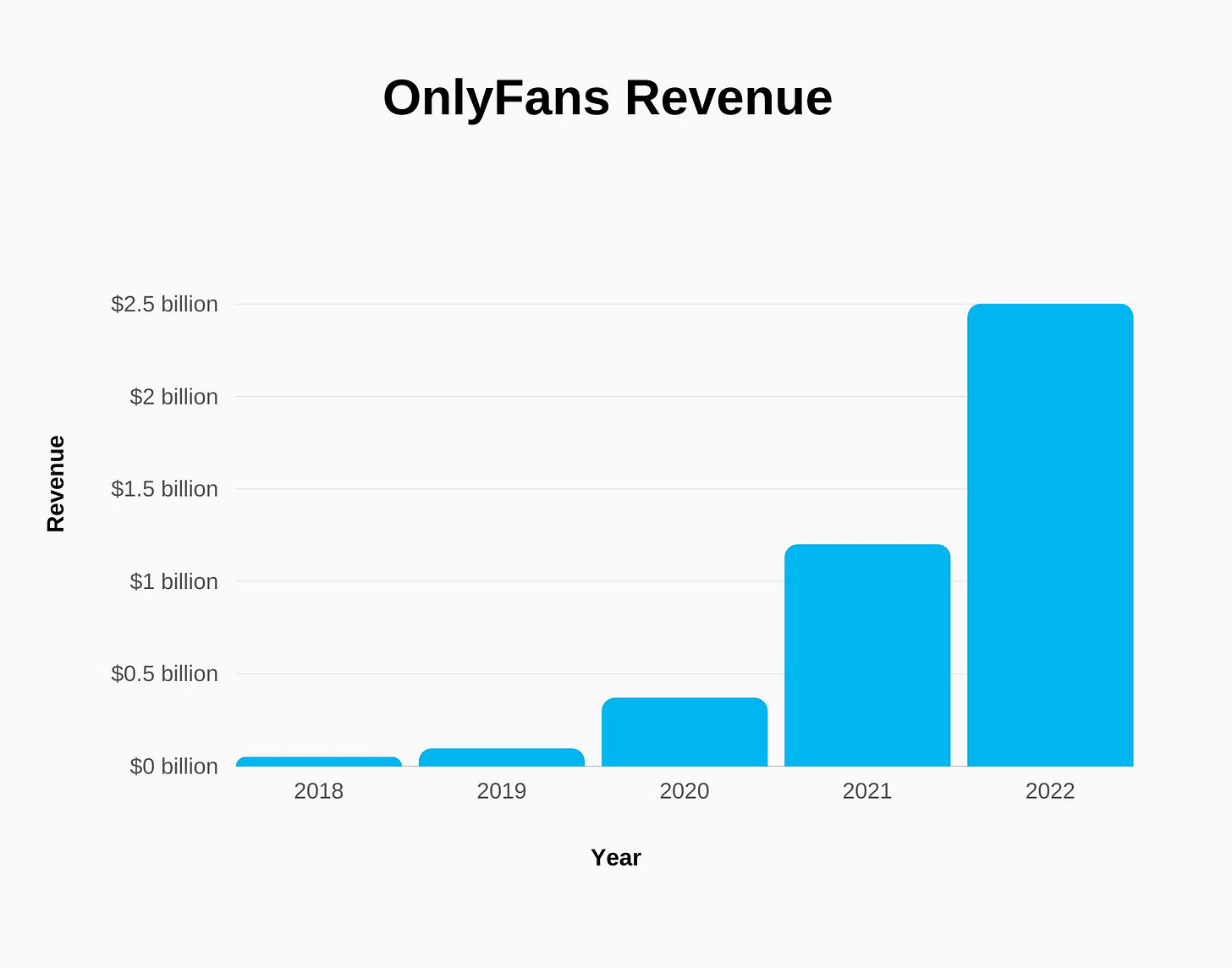

Today, OnlyFans rakes in about $2.5B and grows entirely on its own cashflows, having never taken a cent of venture capital.

To be fair, most venture investors couldn’t have touched OnlyFans if they wanted to; LP agreements typically have a clause preventing investment in pornography and sex work.

Somewhat-adjacent players have emerged alongside OnlyFans, like Passes, with varying degrees of NSFW content; an open question remains: can the OnlyFans model of subscription + micropayment work without pornographic content?

But OnlyFans is the most prominent example of a broader and growing trend: innovative businesses finding savvy ways to earn a living for internet workers.

There’s a long tail of other “internet work”—the makers of sneaker bots, for instance, or the community managers for reselling and e-commerce groups. Many manage their businesses using e-comm tools like those on Whop; many run their banking through startups like Found.

But the entire infrastructure that supports America’s robust small business ecosystem needs to be built to cater to the nuances and complexities of running a small internet business. In the coming years, we’ll see more startups focus their attention on this growing class of SMBs.

Final Thoughts

I’m sure there are many other groups overlooked by tech; I’d be curious to hear what other ones people think of. Each group is an opportunity. It’s often advantageous—for both entrepreneurs and VCs alike—to look at overlooked areas: competition may be lower, opportunities may be more greenfield, and there may be more alpha to generate. As eyes flock to the tech flavor of the month, it’s worth taking a deep look at tech’s longstanding blind spots.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: