The Egg Theory, Applied

The User Psychology of AI Agents—in Shopping, Healthcare, and Enterprise

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 60,000+ weekly readers by subscribing here:

The Egg Theory, Applied

A few months back, I wrote about one of my favorite stories in consumer psychology—the egg theory—and how it applies to AI applications.

When instant cake mixes came out, they sold poorly. Making a cake was too quick and simple. People felt guilty about not contributing to the baking.

So companies started requiring you to add an egg, which made people feel like they contributed. Sales soared. It turns out: there’s such a thing as too easy—and not just with eggs.

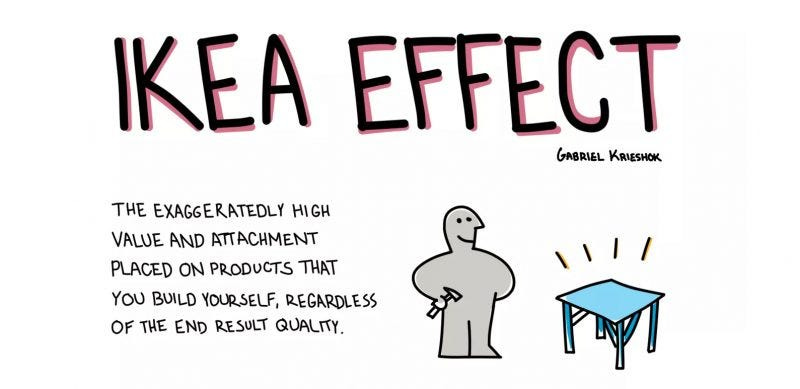

A cousin of the egg theory is the IKEA effect, a cognitive bias that helps explain why people place higher value on things they helped to build or create. In studies, participants have been willing to pay up to 60% more for furniture they themselves assemble, and to be less willing to part with such products.

In that piece from the spring, I argued that the egg theory and the IKEA effect can teach us a lot about AI agents and which products will prevail.

In most use cases, AI products shouldn’t totally remove the human from the loop; people like control, or at least the semblance of control. Good product design means figuring out the trade-off between convenience and user effort.

Over time, as we see AI’s application layer evolve, I continue to feel strongly that the egg theory is a crucial lesson. A key question for builders right now: how much human involvement is too little, how much is too much, and how much is juuust right? As we become accustomed to using AI, we intuitively search for the Goldilocks product—the product that delivers just enough automation, yet just enough control.

AI is, in my ways, an interface revolution. We’re re-learning how to interact with technology. So far, chat is the predominant interface—we’re talking to AI agents, prompting and nudging and adjusting. In the spring, I argued that sometimes the prompt itself is enough of an egg. When I use Midjourney, I feel that my prompt-writing is a sufficient contribution.

Prompt: “A robot is baking a cake and adding an egg to the cake mix. The kitchen is bright and white.”

Midjourney goes one step further, introducing yet another moment of friction by producing four designs for me to choose from. This adds more human involvement, sure, but barely—at the same time, it makes me feel like I did some of the work in graphic design. I feel happier with the end result.

As the human, I make both the first decision (the prompt) and the final decision (which image we go with) in the creative process. The messy middle—the time-intensive part—is what’s removed.

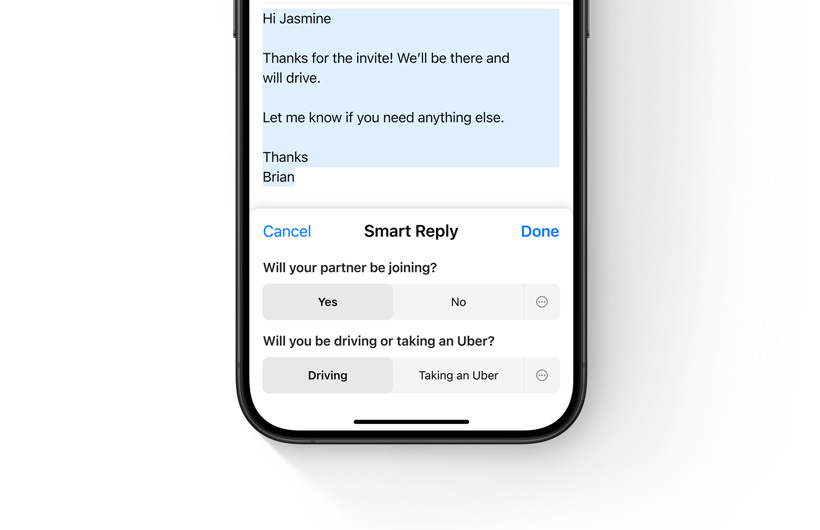

We can see companies figuring out in real time the right mix of ease and effort. One example is Apple, which is bringing generative AI to the iPhone and calling it “Apple Intelligence.” One example Apple offers is “Smart Reply” for emails. In the company’s words:

Use a Smart Reply in Mail to quickly draft an email response with all the right details. Apple Intelligence can identify questions you were asked in an email and offer relevant selections to include in your response. With a few taps you’re ready to send a reply with key questions answered.

Notice how Apple still involves the user quite a bit (you’re the one deciding what content the email should have) but things are packaged in a more efficient multiple-choice format that removes the time-intensiveness of writing an email. You’re still in the driver’s seat—you just get a boost from an intelligent feature and an intuitive interface.

We saw a similar dynamic when OpenAI rolled out plugins last year. In Greg Brockman’s TED Talk, he demonstrated ordering groceries on Instacart using the ChatGPT plugin. You can see in the images below that Instacart’s interface still has an important role to play here; a user is ported over to Instacart and can edit their shopping cart.

This is important: I’d probably be upset if ChatGPT ordered $100 of groceries for me without my sign-off. Yet plugins abstract away the monotonous task: searching for groceries and adding them to my cart. The human input here is a quick scan of the cart and a final approval. Again, the messy middle is what’s gone.

These are big companies grappling with product design. But we’re also seeing startups working to figure out the egg theory in real time. I see this with our Daybreak companies—let’s look at three examples in practice:

One of my companies is building AI-powered shopping—a topic we’ve covered in Digital Native, most recently in May’s The 10 Forces Shaping Commerce. Essentially, with this company, everyone gets an AI stylist they can chat with. In some ways, it’s like Stitch Fix—except the human stylist is now an LLM.

A sample conversation might start:

Shopper: “I’m looking for vacation outfits for my trip to Italy, sort of like they wear in White Lotus.”

This is powerful—instead of searching for “women’s white blouses” or “men’s chino pants in medium” you can shop in a more organic, conversational style. In the background, of course, the AI is drawing from a lot of data—basically every article of clothing across the web. In my mind, this is the biggest shift in commerce: new technology allowing a more natural form of discovery-driven shopping.

A product like this brings up interesting questions of product design. One option might be for the AI to output fully-finished outfits. Voila. But that could be too uncomfortable for the shopper, who wants a bit more control. A better approach might look something like this, balancing ease-of-use with human input:

Shopper: “I’m looking for vacation outfits for my trip to Italy, sort of like they wear in White Lotus.”

AI: “Sure, what do you think of these dresses?”

Shopper: “These are great but I want some pants too, and lots of t-shirts.”

AI: “Great, here’s a mix of both. How are the colors looking to you?”

Shopper: “I want them brighter and bolder. And you can you add accessories too?”

This is still an order of magnitude more efficient than our old way of shopping—but these carefully-chosen bits of friction deepen the interaction and ultimately increase user happiness with the product. Sometimes the fanciest solution—the AI showing off its full capabilities—isn’t the best solution.

To take another example, one of our companies in Stealth is building software for REIs (reproductive endocrinologists and fertility specialists) to manage the IVF and egg freezing process. Here, the AI agent is assisting the REI—a healthcare worker—in her work. Adding moments of human involvement is key not only for user happiness, but for trust and safety. An REI might be a bit alarmed by an AI that spits out: “Give this patient 20mg more medication.” That same REI will respond better to an AI that says, “Patients with similar profiles have benefited from additional hormones—consider whether this patient would benefit from upping [X] medication.” In industries like healthcare, AI augmentation is better than AI automation—this translates into product design that firmly keeps the human in the driver’s seat.

One final example: another of our companies is building a suite of AI tools that can run growth experimentation for a company. Instead of a growth manager having to manually run a bunch of A/B tests—draining engineering resources in the process—the manager can use AI to constantly run experiments optimizing paywalls and upsells and conversions. An interesting question here is: how involved should the growth manager be?

We want to save her time, sure—but we also want her to feel like she still has an important role to play, and that she isn’t taking her eyes off the road. The best design here likely involves suggestions from the new product (“Hit ‘approve’ to run this paywall test on this segment of users”) but manager approval to implement the test.

This tracks with examples above—any time there’s a big decision to be made that consumes resources (time and money), human involvement is key. Even if the AI could do a better job without us—and in many cases, it probably can—giving the human a role in the workflow maximizes user happiness and helps us adjust to a new world order of AI agents.

Our piece from earlier in the year concluded:

Winning products, rather, will be those that offer a bridge from the world of human work to the world of software work, making us feel comfortable and in control along the ride.

This is holding true. I’m always interested in seeing where products draw the line between convenience and effort. I expect that over time, we may “give up” more human involvement, as we become more comfortable with self-executing agents. In the near-term, though, more hand-holding allows for the semblance of control, which ultimately increases user happiness—we prefer cupboards and tables that we ourselves build, and we likewise prefer AI products that we play a role in.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: