The 10 Forces Shaping Commerce

From Ozempic to Overstock, AI Customization to Wellness

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 60,000 weekly readers by subscribing here:

Hey Everyone 👋 ,

This week, Digital Native hit 60,000 subscribers. Thanks for being a part of this growing community :) If there are ever ways I can improve Digital Native, let me know—I’m always open to feedback.

With that, on to this week’s piece…

The 10 Forces Shaping Commerce

We know that GLP-1 agonists, more colloquially known as Ozempic and Wegovy, are all the rage. GLP-1s are expected to compound at a 53% CAGR (!) through 2030; from JPM research:

Some of the winners from GLP-1s are clear: Novo Nordisk, the Danish drugmaker behind Ozempic and Wegovy, sits at a $450B market cap, up more than 100% in the last 18 months. The company has taken LVMH’s crown as Europe’s most valuable company, and its market cap now surpasses Denmark’s GDP. (Ozempic is the name of the drug used to treat type 2 diabetes that also has weight loss effects; Wegovy is the name of the drug specifically prescribed for weight management. Both are made by Novo Nordisk.)

Other winners are less obvious. What are the downstream effects?

I was chatting last week with a friend who works in consumer products. He mentioned a new trend he’s seeing: the rise of ointments for stretch marks. With GLP-1s causing widespread weight loss, stretch marks are becoming more common; naturally, this creates a market for products to get rid of them.

Commerce interests me because it’s both the product of technological change and behavioral change. The clamor for GLP-1s and stretch mark ointments showcase both—breakthrough innovation and cultural ripple effects.

Global retail is a $25 trillion market, with e-commerce comprising about $9 trillion. To put that in perspective, the global advertising market (which is the lifeblood of behemoths like Alphabet, Facebook, Snap, Twitter, and Pinterest) is around $700B. Digital advertising is about half that. Commerce is big; it seeps into nearly every part of life. Humans have been doing it a long time, since the first recorded forms of commerce in 10,000 BC when people traded cattle. (The Latin word for money, pecunia, comes from the Latin word for cattle, pecus.) And we’re still transacting nonstop, through websites and apps and, increasingly, chatbots.

I’ve written about big shifts in commerce in the past, namely in spring 2022’s Talking Shop: The Transformation in Commerce and in spring 2023’s The Retail Revolution. It’s time for a spring 2024 refresh.

The focus of this week’s Digital Native is 10 forces shaping commerce—areas I find interesting and where I see opportunity for startup innovation.

Let’s dive in 🛍️

1) Search, Reinvented

In the future, we’ll be surprised that we ever searched with exact words.

2024 search: “dark blue jeans” “black crop top” “gold necklace”

2025 search: “going out outfit”

That’s oversimplified—2024 search is already more modernized than this lets on—but search is undergoing an overhaul. The new search might even be more specific: “going out outfit like what they wear in Euphoria.” Search becomes contextual, smart, nuanced. It also becomes more conversational. You might chat with a shopping assistant AI who recommends clothes and then makes adjustments until you find something you like.

There are a number of startups working on e-commerce search, and we’re about to see a big shift in user behavior as a result—more natural, casual, conversational search as opposed to the clunky internet speak we learned by necessity.

2) The Wellness Wave

McKinsey sizes the wellness industry at $500B in the U.S. and $1.8T globally. About 80% of American consumers say wellness is a top priority in their lives (though I can’t imagine answering “no” to that question, so it feels like a bit of a leading question). Wellness is a squishy category, encompassing everything from Botox to skincare to melatonin to weighted blankets. That’s a wide range. But the crux is: people care more and more about taking care of themselves, and they’re willing to spend on that self-care.

We see an outsized emphasis on wellness among younger consumers:

We also see wellness as a uniquely American phenomenon. Bloomberg reports that the average American spends $5,108 on wellness each year. The average European, meanwhile, spends just $1,596. (Bloomberg also sizes wellness as a $5.6T global industry—again, it’s a bit squishy to determine what falls into the wellness bucket and what doesn’t. Should healthcare be included, for example, or only non-healthcare wellness spend?)

Wellness is also becoming a rich person phenomenon. I wonder how much of that $5,108 per capita spend is pulled upward by outliers? Equinox recently announced a longevity membership, complete with personalized coaching and diagnostics testing. The cost? A cool $40,000 a year. The entrepreneur Bryan Johnson is famously trying to slow his own aging by spending $2M (!) a year—including on blood transfusions from his teenage son.

I’ve written about wellness a few times this year—namely, in The Huberman-ization of America and The Telehealth Tipping Point. Those pieces go into more depth, but we see innovation across the stack; to take the six categories McKinsey outlines above, example startups are:

Appearance: Med spa software like Moxie and dermatology marketplaces like Honeydew (a Daybreak company)

Health: I’m not sure how “Health” is a sub-category of wellness, but using McKinsey’s definition this would include everything from upstart vitamin brands (e.g., Kourtney Kardashian’s Lemme) to pharmacy startups like Capsule

Fitness: Fitness instruction apps like Future and hardware like Tonal

Nutrition: Dietitian marketplaces like Nourish, food surplus companies like Misfits Market, GLP-1 agonists from companies like Ro

Sleep: Eight Sleep reportedly has impressive numbers, though I still haven’t caved and bought the smart mattress (which starts at around $2K for the mattress topper)

Mindfulness: Therapy marketplaces like Marble Health (a Daybreak company), mindfulness apps like Calm, and high acuity companies like Charlie Health

I’m particularly interested in distribution for wellness products. Direct-to-consumer channels eventually dry up and CACs become untenable. What new channels will emerge? One to watch, in my mind: the doctor’s office. The McKinsey survey shows that physician recommendations are the third-leading driver of purchase decisions:

Expect to see more doctors recommending everything from Nourish to Honeydew to Eight Sleep; companies, meanwhile, will send sales reps to doctors offices to activate this channel.

3) Sustainability

I continue to think Sustainability is the single largest shift bleeding into commerce.

Retailers are responsible for about 25% of global carbon emissions. Scientists estimate that, globally, 35% of the microplastics found in oceans can be traced to textiles. 95.2% of SHEIN clothing contains new microplastics. The good news is that, 1) consumers are waking up to the problem, and 2) they’re pressuring brands to clean up their acts.

There are sub-categories of commerce that will swell as a result of sustainability tailwinds—resale, for instance, which is growing 11x faster than broader retail and which was the subject of last fall’s The Resale Revolution. But I also expect we’ll see both (1) vertical-specific companies for sustainable products and (2) horizontal marketplaces for sustainable products.

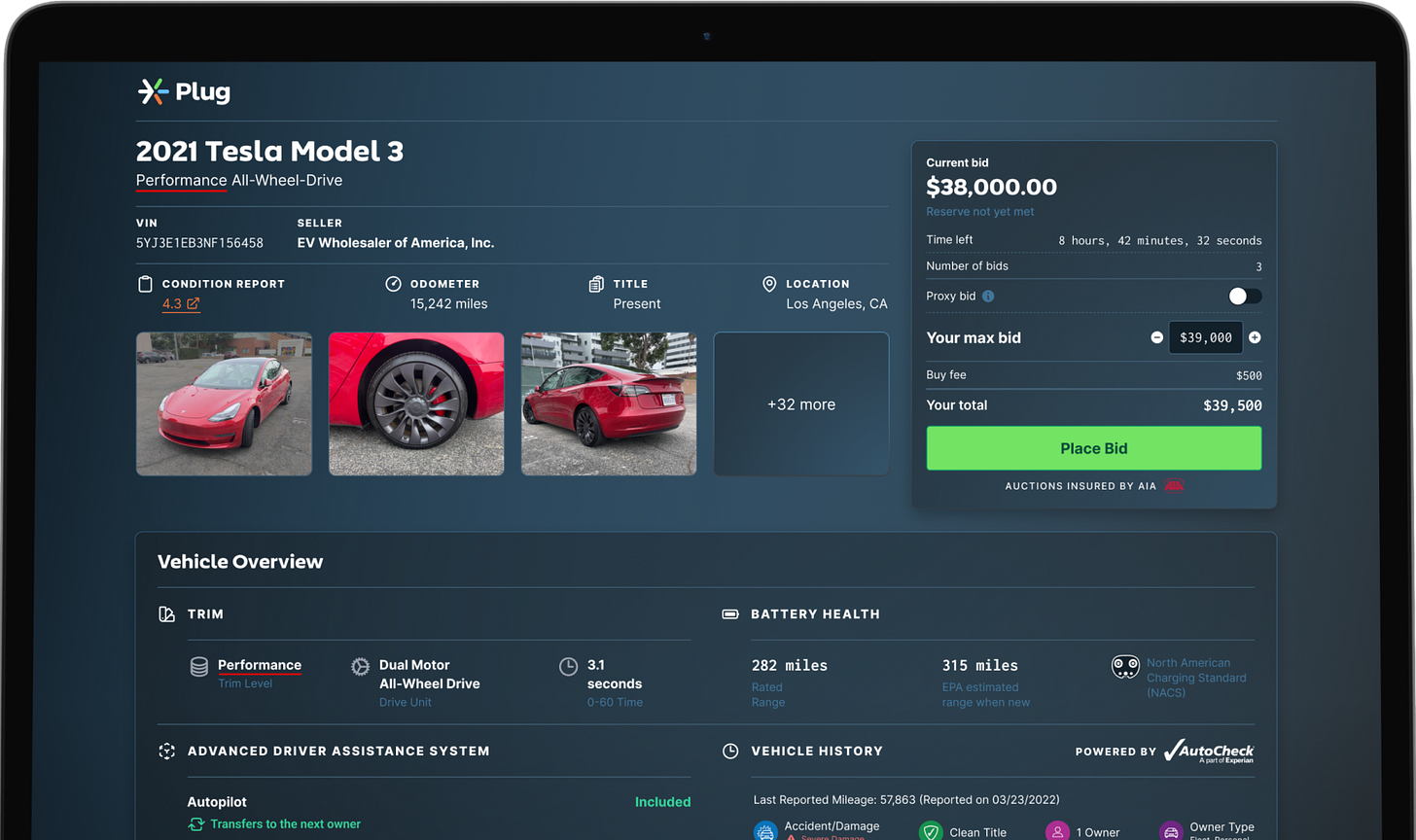

An example of the first, a vertical commerce business: Plug, a wholesale auction that facilitates the buying and selling of used electric vehicles.

EVs are a different animal to buy and sell than regular internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles. EVs are powered by software; when buying a used EV, battery health matters more than the odometer. This requires a different type of marketplace.

The rise of the EV is inevitable—it’s been a long time in the making, with recent tailwinds convalescing to accelerate adoption. Consumers continue to be concerned about climate change; battery technology has advanced enough that EVs can travel further on a single charge; EVs are coming down in price, becoming more affordable to more people. And so on. Most major car manufacturers are full steam ahead on electric, and units sold are up 5x in three years (check out that growth in China 👀):

An example of the second type of business we’ll see emerge, the horizontal sustainability marketplace: ZERO. ZERO is a new startup that aims to be the central hub through which you shop for any sustainable product—or more broadly, any ethical and responsible product. Here are ZERO’s requirements for brands on its site:

This is a new category of commerce. You’ll have Etsy to shop crafts, Farfetch to shop luxury, and ZERO (or the eventual winner) to shop sustainable.

4) Supply Chain

Related to sustainability, we’re seeing a lot of innovation in supply chain. I group this innovation into two main buckets:

Supply chain management

Supply chain transparency

The first is focused on brands and retailers—how can they more efficiently understand and control their supply chain? AI is the enabling tech here, and there are a few interesting startups using AI to streamline supply chains.

The second is focused on consumers. I think it will become table-stakes for a consumer to immediately view the supply chain for a product she buys, including the product’s source, materials, and carbon footprint. This ties into ethical and sustainable consumption, and it’s one of the biggest shifts we’re seeing.

5) Overstock

One of the best final shots in movie history comes from Raiders of the Lost Ark, as a man wheels the ark into an endless sea of boxes. That’s the image that comes to mind when I think about overstock.

Overstock is excess inventory—and it’s a big problem. The back rooms for a lot of stores look a bit like the image above.

Brands overproduce more than $500B of goods annually, and much of it ends up in landfills. In 2017, a Swedish power plant abandoned coal as a source of fuel, instead choosing to burn mountains of discarded clothing from H&M. You can’t make this stuff up.

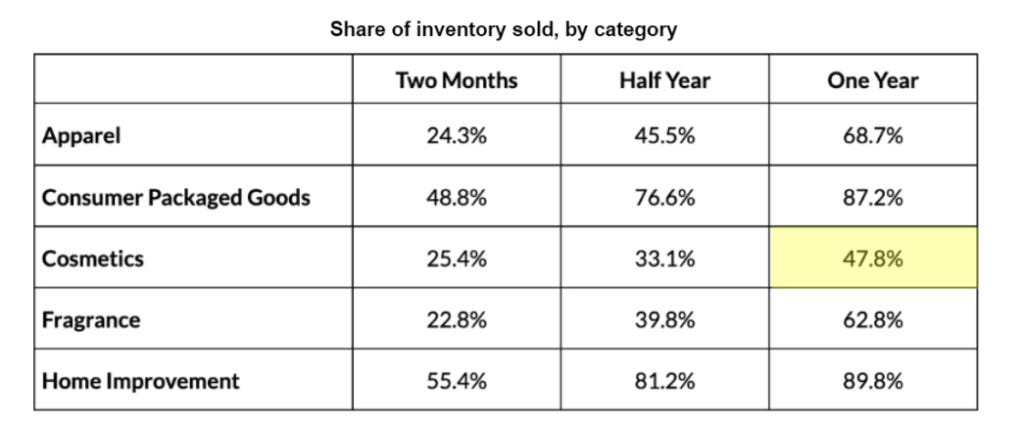

I’ve written about this topic before, but I believe it remains a huge opportunity (perhaps the opportunity) in commerce. Talk to any brand about what keeps them up at night, and the answer is overstock. Some marketplaces exist for brands to offload excess product, but those marketplaces are rarely tech-centric or turnkey; they resemble services businesses with people working the phones. We need good software. Many existing players are also apparel-focused, while other categories have even worse overstock issues; here’s a chart that shows that beauty sells less than half (!) of inventory each year:

Every brand has an order of preference for what to do with excess products. Can you sell to a discounter like TJ Maxx? If not, can you donate? If not, can you ethically liquidate? Brands and retailers need software to manage these decision trees.

6) Design-to-Make, Make-to-Order

This week, an ad blew up on TikTok that was generated by AI. The ad features a real-life creator, only AI is using her likeness to synthetically generate an ad about cleaning wipes. The video is pretty convincing, a little alarmingly so.

There’s no doubt that AI will begin to power ads—user-generated content will become user-generated generated content. This was the argument in last summer’s piece Barbie and the AI-Generated Internet.

But AI’s impact on commerce will go beyond AI-generated ad copy. We’ll also have AI-generated products. Here’s a pair of shoes I designed in Midjourney; they took me about 15 seconds to design, using the prompt:

A pair of Nike shoes are sitting on a pedestal for display. They are vibrant and neon, with bright green swooshes and thick orange soles. They are sleek and elegant.

Pretty soon, I imagine I’ll be able to design shoes like this and order them from Nike. I think of this in two components:

“Design-to-make” means using AI tools to design products myself, rather than selecting from pre-designed products; this is powered by generative AI, like the Midjourney example above.

“Make-to-order” means then ordering those designs, made possible by innovations in manufacturing and robotics.

Startups that enable this sort of personalized commerce will sell into brand and retailers, underpinning custom designs and orders. Imagine Nike embedding a personalized product design tool, or using supply chain software that manages custom made-to-order manufacturing.

We’re already seeing personalized products becoming commonplace for digital products. To build on the wellness category above, one survey found that 20% of U.S. and U.K. consumers and 30% of Chinese consumers look for personalized health products customized with their biometric data. Generative AI can then design customized health plans based on user health data. This level of personalization will soon extend to physical products, with our own data and preferences informing what products we purchase.

7) Creator & Social Commerce

Amazon is utilitarian shopping. It’s void of emotion. Amazon is search-driven: when a Prime member visits Amazon.com, they end up buying something 74% of the time.

No one, meanwhile, has really figured out discovery-driven commerce online—a way of recreating the browsing, serendipity-fueled experience of 20th-century shopping malls. We’re (finally) seeing some companies pioneer forms of discovery-driven shopping, primarily through creator commerce and social commerce.

One example: our first investment at Daybreak was in Flagship, a company I wrote about last summer in The Future of Creator Commerce. Flagship lets any creator launch and manage her own online boutique—a small business showcasing her favorite products. Youssef Ahres, Flagship’s co-founder and CEO, shared on LinkedIn this week that Flagship had its first creator drive over $1M in sales, taking home north of $200K herself. Other creators, meanwhile, are earning passive income on their storefronts, while some have hired employees to run and manage their Flagship boutique as a business.

Creator and social commerce still have a long way to go—the West pales in comparison to behemoths like Xiaohongshu in Asia—but we’re seeing a lot of innovation here. As long as commerce has existed, two things have held true: (1) shopping is inherently social, and (2) purchase decisions are built on recommendations from others. The question is, what are the right business models to monetize those two truth?

8) The Bifurcation of Creator Brands

People are tired of influencer brands; you can see this exhaustion in the comments on new brand announcements. One recent TikTok announcing a new Brad Pitt brand was littered with negative comments—at best, apathy; at worst, anger.

My view: we’re going to see a splitting of creator brands into two categories. One segment of creator brands will never find success. Those brands just won’t resonate with consumers; they’ll seem inauthentic and like a cash-grab. The other half—which will be just a handful of brands—will become generational businesses.

An example of the first category is Beyoncé’s Ivy Park. The WSJ reported last year that Ivy Park, Beyoncé’s partnership with Adidas, saw its sales fall 50% in 2022. Adidas projected $250M in 2022 sales, but the brand only brought in $40M. Ouch. Ivy Park is now set to lose about $200M a year for Adidas. (My take is that Beyoncé’s aspirational, somewhat-aloof persona is at odds with Ivy Park’s athleisure style. She should have created an ultra-luxury brand.)

Three examples of creator brands that may be generational brands: Kim K’s SKIMS, Rihanna’s Fenty, and Logan Paul & KSI’s PRIME. What do they have in common, other than a lot of capital letters? Each one had a net-new product insight, distinct from its celebrity figurehead. The insights:

SKIMS: Shapewear is outerwear.

Fenty: Make-up should come in more shades for people of color.

PRIME: Energy drinks are a good idea—but let’s try one without sugar that still tastes good.

PRIME did $1.2B in revenue last year. SKIMs did $750M, up 50% from $500M in 2022. Fenty sales reportedly hover around $600M. These are monster brands, and they aren’t showing signs of stopping; each brand has transcended its creator (which helps long-term durability) and each brand has injected new energy into a stale category.

I think we’ll see fewer and fewer celebrity brands launch—most just aren’t working. But the ones that do work will work better than anyone could have imagined. We’ll see a Pareto principle: 80% of creator brand value will come from 20% of creator brands.

9) New Brand Categories

The stretch mark ointment above is an example of a new brand category—or an existing, but still nascent brand category that’s now experiencing outsized growth.

At Daybreak we don’t invest in brands (we focus on internet, software, and AI applications) but I like to keep a pulse on what brand categories are emerging; new brand categories often have ripple effects through the broader e-comm landscape. Often, the same trend can produce brands and enablement businesses—for instance, cannibis powered the rise of wholesale marketplaces like LeafLink and brands like Cann (which I’ll plug here as it’s my friend’s company—buy Cann!).

The Cann example also speaks to another emergent category: non-alcoholic beverages, growing +7% annually through 2027 and particularly popular amongst Gen Zs. That growth is a direct result of a new consumer behavior. Brand categories are typically the result of new behaviors, savvy marketing, or the combo of the two.

10) Dynamic Pricing & Auctions

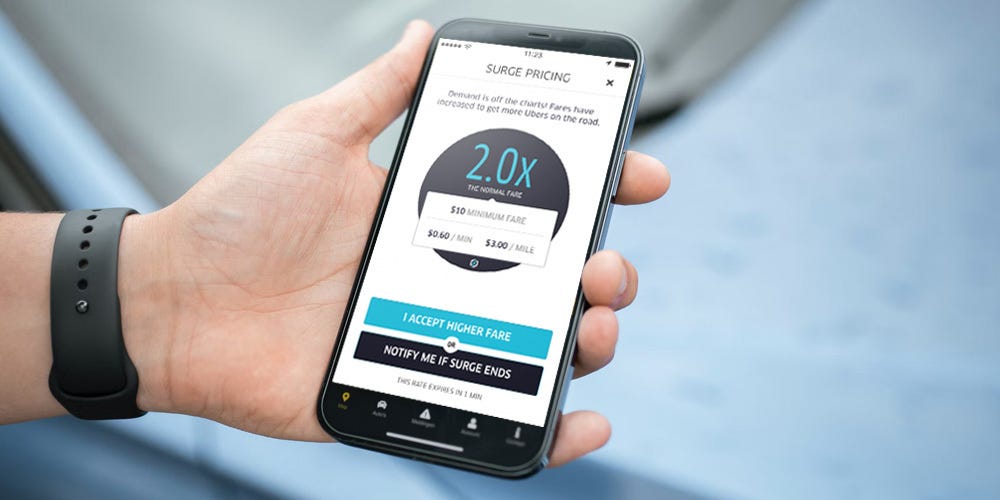

I’ve always been fascinated by pricing. The story of commerce is the story of innovation in pricing. One famous example from the 2010s is Uber’s popularization of surge pricing—a tactic that Wendy’s recently borrowed to enormous backlash.

Probably the best example of price innovation comes from the airline industry. From a recent piece by Christopher Beam in The Atlantic:

In his book Revenue Management: Hard-Core Tactics for Market Domination, the pricing consultant Robert Cross recalls watching a Delta employee hand out discounts for the last empty seats on a flight in the early 1980s. Cross knew the plane would fill up with business travelers at the last minute, so he suggested holding those seats and charging a higher fare. This idea—selling seats for a lower price if you book early and a higher price later—transformed the airline industry, and saved the legacy airlines.

From there, the field of revenue management, or adjusting price and availability based on real-time shifts in supply and demand, boomed. Multitiered pricing spread to airline-adjacent industries like hotels and cruise lines, and then beyond to telecoms, manufacturing, and freight. Companies adopted sophisticated software to track real-time supply and demand, and started hiring pricing consultants or even in-house pricers.

Another example of pricing innovation is the advent of fees, which anyone who’s booked a trip on Booking.com or bought concert tickets through StubHub understands all too well. From The Atlantic:

The rest of the travel and events industry followed suit. Mysterious “resort fees” appeared on hotel bills. Car renters burned time poring over “facility fees,” transponder fees, and third-party insurance. Ticketing websites charged markups as high as 78 percent for concerts. Some fees sounded like jokes. In 2014, an airport in Venezuela charged customers a fee to cover its ventilation system, a surcharge widely mocked as a “breathing tax.” And fees mingled with the broader trend of digitization-enabled unbundling. Want to “unlock” your Tesla’s full battery life? In 2016, that cost an extra $3,250.

What comes next in pricing innovation? Probably usage-based pricing for AI tools. From last month’s Weapons of Mass Production:

My view is that the dominant business model for AI production tools will be a freemium model. You’ll get some amount of production for free, above which you’ll have to pay.

You might have to pay a flat subscription, but I suspect more common will be a credits-based system. This ensures that payment is tethered to volume (and thereby underlying costs of generations), with some people generating much, much more than others. You might get your first 10 credits free, enough for a 60-second video clip. To get another 10 credits and another 60 seconds, you’ll need to pay $9.99. Or maybe I can feed a voice generator a 100-word script for free, but I have to pay another few bucks for every additional 100 words.

I expect we’ll continue to see a lot of dynamic pricing, and a lot of volume-based pricing for AI tools.

Final Thoughts

Innovation in commerce is diverse and wide-ranging—from Shopify plug-ins, to payment flows, to AI-generated product detail pages. With innovation, everyone wins: it’s never been easier to launch a brand, to open a storefront, or to shop. Every aspect of the transaction experience is being reimagined from first principles, built in a more efficient, flexible, and affordable way.

Shopping in 2034 will look meaningfully different than shopping in 2024.

Related Digital Native Pieces:

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week:

![r/dataisbeautiful - [OC] EV sales have accelerated globally, growing 5x in 3 years r/dataisbeautiful - [OC] EV sales have accelerated globally, growing 5x in 3 years](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!VnGz!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa15be9e6-70b5-4112-8ef4-94a5ace58ed1_640x640.jpeg)