The Hyper-Personalization of Everything

What the Industrial Revolution Was to Physical Production, the AI Revolution Is to Digital Production

Weekly writing about how technology shapes humanity and vice versa. If you haven’t subscribed, join 50,000+ weekly readers by subscribing here:

The Hyper-Personalization of Everything

If there’s one TikTok phenomenon that embodies Gen Z culture, it’s Bean Soup.

Let me explain:

On TikTok, it turns out that a lot of people like bean soup. So much so, in fact, that it’s become quite popular for creators to share their favorite bean soup recipes. So far, so good; seems straightforward enough.

Reading through the comments on bean soup videos, though, you start to see a trend: many people ask the question, “But what if I don’t like beans?”

The answer, of course: then don’t make bean soup (!). But most people can’t grasp that the videos might not be a fit for them. One creator calls this the “What About Me Effect.” The “What About Me Effect” combines individualistic culture with being chronically online. It means that we assume that everything should in some way apply to us—that we should be accommodated for our personal, nuanced situation.

The internet noticed the ridiculous slew of “what if” questions on bean soup videos, and turned it into a running joke:

The whole meme is hilarious, but the underlying phenomenon is revealing. It’s symbolic of an entire generation; we’ve come to expect every experience to be hyper-personalized.

Even before the internet, American culture was shifting from communal to individualistic.

The frequency of the word “I” in American books doubled from 1965 to 2008. A study of magazines found that themes of family dominated in the 1950s—“Love means self-sacrifice and compromise”—only to be replaced by themes of independence in the 1960s—“Love means self-expression and individuality.” Baby Boomers came of age with the cultural language of liberation (think Bruce Springsteen’s “Born to Run”), while Gen Xers and Millennials were taught the importance of being special and unique (think participation trophies).

Family structures, meanwhile, changed rapidly. From 1970 to 2012, the share of households consisting of married couples with kids was cut in half. Single-person households rose from 13% to 28%. A century ago, 75% of Americans older than 65 lived with relatives; by 1990, only 18% did. In a 1957 survey, more than half of respondents said that unmarried people were “sick,” “immoral,” or “neurotic.” Today, being unmarried doesn’t even merit a shrug. (By the way, Pew Research estimates that 25% of Millennials will never marry.)

From the most recent edition of 10 Charts That Capture How the World Is Changing:

Culture is becoming more “me”-centric. What’s fascinating to me is the role that technology plays in enabling and accelerating individualism.

Last week’s piece was about technological shifts—from the Industrial Revolution, to the Mobile Revolution, to today’s AI Revolution. This week’s piece is about a large-scale cultural shift—the rise of hyper-personalization—that’s no less influential on the startup ecosystem and the generational businesses being built.

Consumerism has become more and more personalized. The 2010s brought the explosion of direct-to-consumer brands—digitally-native businesses powered by direct response advertising. Many DTC brands leaned heavily into personalization. Curology brought you personalized skincare; Prose brought you personalized haircare; Care/of brought you personalized vitamins. Stitch Fix offered everyone a personal stylist, fusing data science with human stylists to rake in over $1B in annual sales (though with many headwinds today).

As consumers, we became accustomed to everything being tailored to us. This was the capitalist manifestation of the “we’re unique and special” mantras we absorbed in kindergarten. The internet was the enabler.

This shift extended beyond commerce to content. The last decade introduced the phrase “peak TV” into the media vernacular, with 599 scripted TV shows in 2022—something for everyone.

YouTube’s homepage was tailor-made with recommendations built around our tastes and preferences. Likewise for Instagram’s Explore Feed. TikTok named its feed the “For You Page,” a not-so-subtle nod to the personalization of the algorithm. As one commenter notes on a Bean Soup-related video:

There are also the invisible companies underpinning personalization. Last month’s The Wild West of E-Commerce dug into Klaviyo, which IPO’d on September 20th and boasts an $8.5B market cap. Klaviyo lets brands personalize their marketing to you—chances are you’ve received a text or email powered by Klaviyo that mentions you by name.

My broad thesis on the consumer ecosystem (including both B2C and B2B businesses) is that the consumer experience follows a steady arc toward 1) more convenient, 2) more affordable, and 3) more enjoyable, with technology acting as the force bending the arc. More enjoyable often means more personalized—more customized to our distinct wants and needs.

This is a good thing. Yes, the Bean Soup saga is eyeroll-inducing, but we should be spoiled by products and services that are tailor-made for us. More customization means more willingness to pay and more alignment between company and customer, leaving less deadweight loss (remember that term from Econ?). We’ve seen this arc play out since the Industrial Revolution and the automobile introduced mass production and mass consumption—more on that in a bit.

To illustrate the benefits of personalization, consider three compelling startups each delivering more personalized health experiences:

GetHarley, a London-based startup, matches you with clinicians for personalized skincare consultation. I remember working the phones in New York trying to find a derm to see about retinoids (I just turned 30, after all); GetHarley is a marketplace that solves that problem, making tailored derm recommendations more accessible.

Summer Health is a New York-based startup offering parents a way to text instantly with a pediatrician. Pediatric care is often bespoke. The average parent visits their pediatrician 10 times a year during the child’s first two years, and four times a year thereafter—and that’s despite often long wait times. Summer Health’s founder, Ellen DaSilva, came up with the idea when her newborn had a health issue in the middle of the night and she couldn’t reach her pediatrician. Her company’s mission is to broaden access to pediatric care through a one-to-one, personalized interaction via telehealth.

Nourish, also New York-based, connects you to a dietitian covered by insurance. Everyone’s needs are different—you might have an autoimmune condition, an eating disorder, diabetes. You might need to lose weight, but lack the specificity on how your body should approach weight loss. Nourish makes heavily-personalized guidance affordable and convenient.

Personalized health is made uniquely accessible by technology; the space is one example of how startups can better deliver personalized products and services to consumers. Ultimately, the winner is you—you benefit from hyper-personalized offerings that make your life better.

What’s exciting is that we’re still at the cusp of personalization—everything is about to get even more personalized with AI models tailored to our incredibly-specific tastes and preferences.

When we step back, we see that successive technologies have historically increased personalization.

To begin with, the Industrial Revolution gave us mass production.

Marketing, in its modern form, essentially didn’t exist before the Industrial Revolution. There was such little product differentiation that it simply wasn’t necessary. Then manufacturing exploded, and production became cheaper and faster than ever before. New entrants crowded the market, and marketing became essential. Today, marketing is often all that distinguishes a product. (June’s essay How to Build Your Startup Brand explored the growing importance of brand.)

Marketing rules our consumerist society. Children as young as two can recognize brands on shelves, and by age 10 children have recognition of 300 to 400 brands.

While the Industrial Revolution enabled mass production, the advent of the car really shifted things into gear (pun intended) on mass consumption. The automobile—kickstarted by Henry Ford’s Model-T in 1908 and powered by the innovation of the assembly line—led to offshoot industries like the shopping mall and the credit card.

All of a sudden, consumer choice was abundant. The average supermarket has 250 (!) brands of cereal in its cereal aisle.

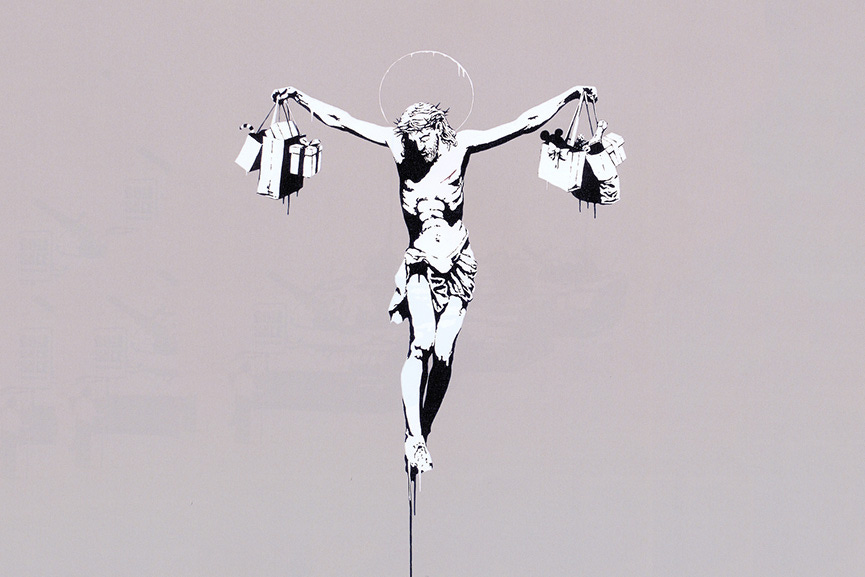

Mass consumerism even bled into the art world. The movement known as Pop Art emerged in the 1950s to both celebrate and criticize American mass production and mass consumption. Over half a century, Pop Art has delivered works like Andy Warhol’s “Campbell’s Soup Cans” (1962) and Banky’s “Christ with Shopping Bags” (2004). They epitomize 20th-Century American consumerism, which went hand in hand with growing personalization. When you have the choice of 250 cereals, you’re bound to find something you love.

Beginning in the 1990s, the internet came along and unlocked distribution. Anyone could connect with anyone or anything. When I think of the internet’s personalization, I think of Discord’s 19 million weekly active servers; everyone can find community and belonging. Or I think of Reddit’s 4 million subreddits, including bizarre communities like r/SEUT (Squirrels Eating Unusual Things), r/HorseMask (photos of people wearing those horrifying rubber horse masks), or r/gggg (a community in which you are only allowed to type the letter g). Each has thousands of members, an indicator of the breadth of internet niches.

The point is: the internet fragmented culture and consumerism even further.

I was reminded of this again when reading last month’s Forbes List of the 50 Highest-Paid Creators. As someone who was once described as “extremely online,” I still only recognize half the list. The internet blew open the floodgates of content and connection. Fragmentation led to greater personalization and to more “me”-centric culture.

Finally, we have the arrival of AI. If the Industrial Revolution brought us mass production in the physical world, AI is bringing us mass production in the digital world.

The Industrial Revolution and automobile made it possible for you to choose from 250 varieties of cereal. AI’s mass production lives in the world of bits, not atoms. You’ll be able to choose from 250 AI chatbots or 250 AI-generated forms of entertainment.

We’re already seeing examples of AI delivering on the next wave of hyper-personalization.

Meeno is a new app that offers a personal relationship mentor—someone to talk to about problems you’re facing with friends and family and loved ones. This builds on the explosion of more horizontal chat apps earlier this year—Chai, Replika, and so on.

In 1990, it would have been unthinkable that people in 2023 would have close friends they’d never met—yet ~40% of Gen Z reports having a close friend who they interact with only online. The next iteration, in 10 or 20 years, might be considering an AI chatbot to be a close friend. Chatbots tailor-made to what we need in a companion could outmaneuver flawed human relationships. This is somewhat dystopian, of course, and the depth and richness of “real” friendships should remain center-stage—yet a more optimistic view is that this is one way that technology can combat the loneliness epidemic facing America.

We also see highly-personalized vertical applications of AI. Class Companion, for instance, offers students personalized feedback on their assignments. Sizzle, meanwhile, helps learners work through homework problems with personalized AI.

The effects of personalization will be widespread, across every industry. In fashion, brands are using AI models to digest large datasets of runway show images, social media posts, and search data, better assessing what clothes people want. This should help you get the jacket you really want, and it should also help reduce waste from unsold inventory. In healthcare, AI is being used to create data models of individual patients in clinical trials (so-called “digital twins”) which allow researchers to conduct preliminary trails before embarking on expensive or risky trials with real people. This means treatments can be more targeted to those most in need, and conducted more quickly.

Hyper-personalization is one of the largest decades-long shifts. We see it appear in culture, where our expectations have become personalization; we’ve gotten spoiled. And we see enabling technologies like AI arising to make new degrees of customization possible. Soon, everyone should get their own personalized healthcare plan; their own personalized learning path; their own personalized shopping recommendations.

If the 20th Century was about mass consumption, the 21st Century is about “bespoke consumption.” We have more production than ever—the internet and AI both continue to make it easier than ever to produce—but that production is composed of more tailored, customized products designed for individuals, rather than for the masses.

Sources & Additional Reading

This TikTok and this TikTok are good breakdowns of the “Bean Soup” phenomenon

David Brooks’ writing on community is quite good, including The Nuclear Family Was a Mistake (The Atlantic), America Is Having a Moral Convulsion (The Atlantic), and How to Actually Make America Great (NYTimes)

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: