Two Roads Diverged: The Splitting of Venture Capital

Labor vs. Capital, Artisans vs. Asset Managers

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 55,000+ weekly readers by subscribing here:

Two Roads Diverged: The Splitting of Venture Capital

Venture capital has a bad rap. We have…a bit of a PR problem.

In my mind, this is undeserved. I realize this view is self-serving, given that I work in venture and recently started a venture firm, but bear with me.

A 2021 Stanford paper found that venture-backed companies account for 41% of US market capitalization and 62% of US public company R&D spending. Among public companies founded within the last 50 years, the numbers are even higher: VC-backed companies account for half in number, three-quarters in value, and 92% in R&D spending. If entrepreneurship is the engine of innovation, venture capital is the fuel.

Take the 10 largest US public companies—six were venture-backed. Apple and Tesla are the bookends here, with Apple taking its first venture funding in 1977 and Tesla first taking venture dollars in 2004.

This graphic is built on 2020 data and already outdated. If it were refreshed with 2024 data, updates would include the addition of Nvidia, another venture-funded company (first venture dollars: 1993) that now boasts a market cap over $2 trillion.

Venture capital is often (unfairly) lumped in with its cousin, private equity; the latter is a media scapegoat for job loss, and VC is often collateral damage. But research shows that venture funding drives employment growth. A 2022 paper found that employment at VC-backed companies grew 960% from 1990 to 2020, compared to a 40% increase in total private sector employment during the same time period. That growth is also recession-resistant: during the Great Recession, total private sector employment shrank 4.3%, while VC-backed company jobs grew 4.0% annually.

This piece isn’t meant to be venture propaganda; the industry has its shortcomings, and more on those later. But this piece is meant to use hard data to show that when done right, venture should fuel innovation, which in turn fuels economic growth and makes our lives better.

The goal in this week’s Digital Native is to step back, take stock of the industry today, and explore where it’s going. I’ve broken this piece into four sections:

Snapshot of the VC Market

Labor and Capital

The Bifurcation of Venture: Artisans vs. Scaled Asset Managers

Daybreak’s Thesis

Let’s dive in.

Snapshot of the VC Market

Part of the reason that VC’s reputation has soured is because the industry has drifted away from its roots. The industry started acting a lot more like asset management than a niche, cottage industry built on power law outcomes.

This was especially true in the post-COVID ZIRP (zero-interest rate policy) days, when the markets overheated. We can play the blame game, pointing fingers at entrepreneurs for taking money at inflated prices, at VCs for offering those sky-high prices, or at LPs for pouring capital into the asset class in pursuit of yield. But everyone acted as expected, in their own best interest; a confluence of market dynamics simply led to a frothy market that needed an overdue correction.

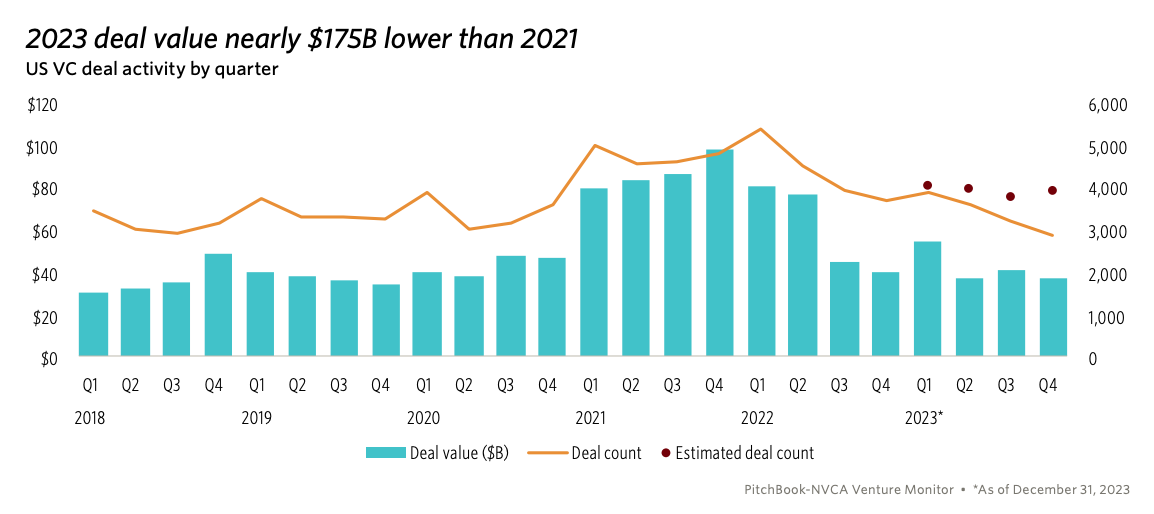

Over the last 18 months, we got that correction. 2023 deal value was down sharply from 2021:

The six quarters from Q1 2021 to Q2 2022 are the outliers here, with the ZIRP phenomenon in full effect post-COVID. That period will be remembered for Bored Apes and mega-rounds led by Tiger. Nearly everyone played a role in the frothiness—again, incentives.

We now see markets cooling across every stage. Late-stage deals have been hardest hit, with the growth markets only starting to show signs of life in the last quarter or two. But Pre-Seed and Seed have also slowed to a 13-quarter low:

I expect the early-stage markets to turn around soon. Downturns typically result in a talent unlock: folks are underwater on their options and leave to start their own thing. Anecdotally, I’ve seen a major pick-up in early-stage activity in Q1 2024 compared to last year. The 2024, 2025, and 2026 vintages will be great vintages for Seed.

Yet I don’t expect capital to become more free-flowing. A key metric to track is capital availability—the ratio of capital demand to capital supply. We’re closing in on 2.0x, a sharp increase from the sub-1.0 levels of the past few years:

I expect this ratio to remain high for a while. Venture fundraising isn’t going to pick up any time soon: LPs aren’t getting capital back, and many are suffering from the “denominator effect.” (LPs like Stanford’s endowment or California’s teachers retirement system have exposure to both public markets and private markets. As the public market goes through a downturn, public assets decline in value; consequently, LPs become relatively overexposed to privates. This is the denominator effect. Put simply, they don’t need more venture exposure right now.)

What’s more, many venture firms already have large coffers to deploy. As early-stage deal flow heats up again, capital demand will continue to outstrip capital supply.

I expect that over the next 24 months, we’ll see a washing out in the venture markets. This will be true both for startups and for venture firms. On the startup side, many companies will raise down rounds or not be able to raise at all; they’ll shut down. Most unicorns shouldn’t be valued at $1B+, and we’re going to see a resulting correction.

For venture firms, we’ll see the same thing. Over the past few years, we saw a boom in first-time funds. Many of these funds overextended themselves during the market froth, and they’ll struggle to raise a second or third fund. The funds that succeed will fit into one of two buckets—artisans or asset managers. More on that in a moment.

Labor and Capital

Earlier this week, I attended the launch event for Scaling Through Chaos, a new founder’s guide put out my former colleagues at Index Ventures. At the event, we heard from Kevin Ryan. Kevin is a legend in the New York tech scene. He’s the former CEO of DoubleClick, selling it to Google for $3.1B (arguably the best acquisition of all time, as DoubleClick powers Google’s $250B+ advertising empire), then went on to found startups ranging from MongoDB ($26B market cap) to Gilt Group to Business Insider to Zola. He now runs AlleyCorp, a prolific startup incubator in the city.

In his talk, Kevin gave an analogy: a founder is like a race car driver. She’s consistently toeing the line between speed and control. Her job is to go as fast as she can without veering off the tracks. It’s like playing Mario Kart; can you out-drive your competitors without running into the walls or slipping on a banana peel?

The founder must maneuver by allocating two resources. When it comes down to it, business is all about allocating just these two resources: labor and capital. People and money. It’s as simple as that. You allocate those resources as efficiently as you can to maximize speed without veering off the tracks.

In venture capital, you give founders money and then you partner with them to get the right people around the table. A founder’s job, meanwhile, is to get capital and talent, then direct that capital and talent into the best possible channels.

Two charts from the ‘Scaling Through Chaos’ book stuck out to me. One embodies something that’s changed over time, and the other embodies something that has stayed the same (and likely aways will).

One change over the past two decades is the time that it takes to scale headcount:

Between 2000 and 2020, the time required for successful venture-backed tech companies to scale to 500 headcount has shrunk for every stage of growth. It used to take these companies more than eight years to get to 500 headcount; now it takes closer to five years.

(This week, both Ramp and Deel celebrated their five-year anniversaries—Ramp on Monday and Deel on Tuesday. Ramp has ~850 employees; Deel has over 2,000.)

Part of the reason for rapid hiring has been easier access to capital. Over the past few years, it was too easy to get money and too easy to spend money. This led to over-hiring for many companies, and a painful market correction with the RIFs (Reduction In Force, a fancy term for layoffs) we’ve seen over the past two years. We may see a slowdown in hiring in this capital environment, particularly as AI allows companies to generate more output per worker.

One thing that won’t change, though: the amount of time that a founder spends on People-related tasks. Once a company has a minimum viable product and has raised its minimum viable amount of funding, most of an entrepreneur’s focus shifts to hiring, HR, and people management. A founder goes from “building a product” to “building a team.” Payroll is consistently the single largest “use of cash” for a high-growth startup, and I don’t see that changing.

The average founder spends about 50% of her time on people “stuff,” though the composition of that time shifts as a company scales:

These charts get to the heart of a single truth: startups are all about people. They’re about money, too, but that money is mostly used to acquire and retain talent. The best venture firms over the next decade will recognize this truth. We’re going to see a “sorting out” in venture capital into people-focused firms and money-focused firms. Labor vs. capital.

The Great Bifurcation: Artisans vs. Scaled Asset Managers

In many industries, we’ve seen a bifurcation into niche and sprawl. Into depth and breadth.

Take the news industry. If you’re thriving in news, you’re likely either (1) narrow, nimble, and focused, like a successful Substack publication with a single journalist, or (2) you’re a multi-product behemoth, like The New York Times. Same thing in media. You’re either CrunchyRoll, a highly-successful streaming service for anime, or you’re Disney, gobbling up Pixar and Lucasfilm and Marvel and Fox. You’re a city-state or you’re an empire. If you’re in the middle, you’re dead.

We’re seeing the same thing in venture. You’re either an artisan or you’re a scaled asset manager. Going back to the two resources that founders can allocate—labor and capital—artisans are more focused on assisting with the labor and asset managers are more focused on assisting with the capital.

Artisans focus on people; they invest capital, sure, but their value really shines in hands-on partnership around attracting and cultivating talent—making sure the right people are around the table. Asset managers are more about the money—their form of venture is less about craft than about putting dollars to work. Naturally, the latter is a better fit for a late-stage company that has a built-out people function and is more focused on getting dollars in the door to keep the engine humming. The former is better for early-stage—the original ethos of venture capital.

A few years ago, Everett Randle made a good analogy—in VC, you’re either selling a luxury product (Tiffany) or you’re mass-market (Walmart). If you’re JC Penney, sitting in the middle, well—your clock is ticking. After the market correction, this bifurcation has only accelerated. We see early-stage-focused artisans, both older firms like USV or IA and newer ones like Daybreak or Equal. I doubt these names ever raise $1B+ funds—and if they do their job right, artisanal funds can return upwards of 10x+.

We’re also seeing asset managers, as firms like a16z and Insight are tasked with deploying billions and billions of dollars (a16z is raising $7B for its latest set of funds and Insight is targeting $15B, sitting on $10B of dry powder).

Over the past decade, we’ve seen an “industrialization” of venture capital. What was once a cottage industry went into overdrive. The product became mass market. It’s not hard to understand why venture ballooned as an asset class: (1) ZIRP drove a huge influx of return-hungry capital into PE and VC, and (2) incentives drive larger funds.

Here’s a good example of why incentives are skewed in venture:

The net present value of management fees alone for a fund at $1,000M exceeds the fees and carry of a fund at $200M, even if it returned 4x. Let that sink in. Bigger funds means more fees, and more fees mean that GPs get rich, regardless of performance.

Daybreak’s Thesis

My vision for Daybreak is a “back to basics” for venture. The industry has overheated and become industrialized, leaving a gap for artisanal firms focused on early-stage partnership. Daybreak is modeled after the USVs and IAs of a prior generation.

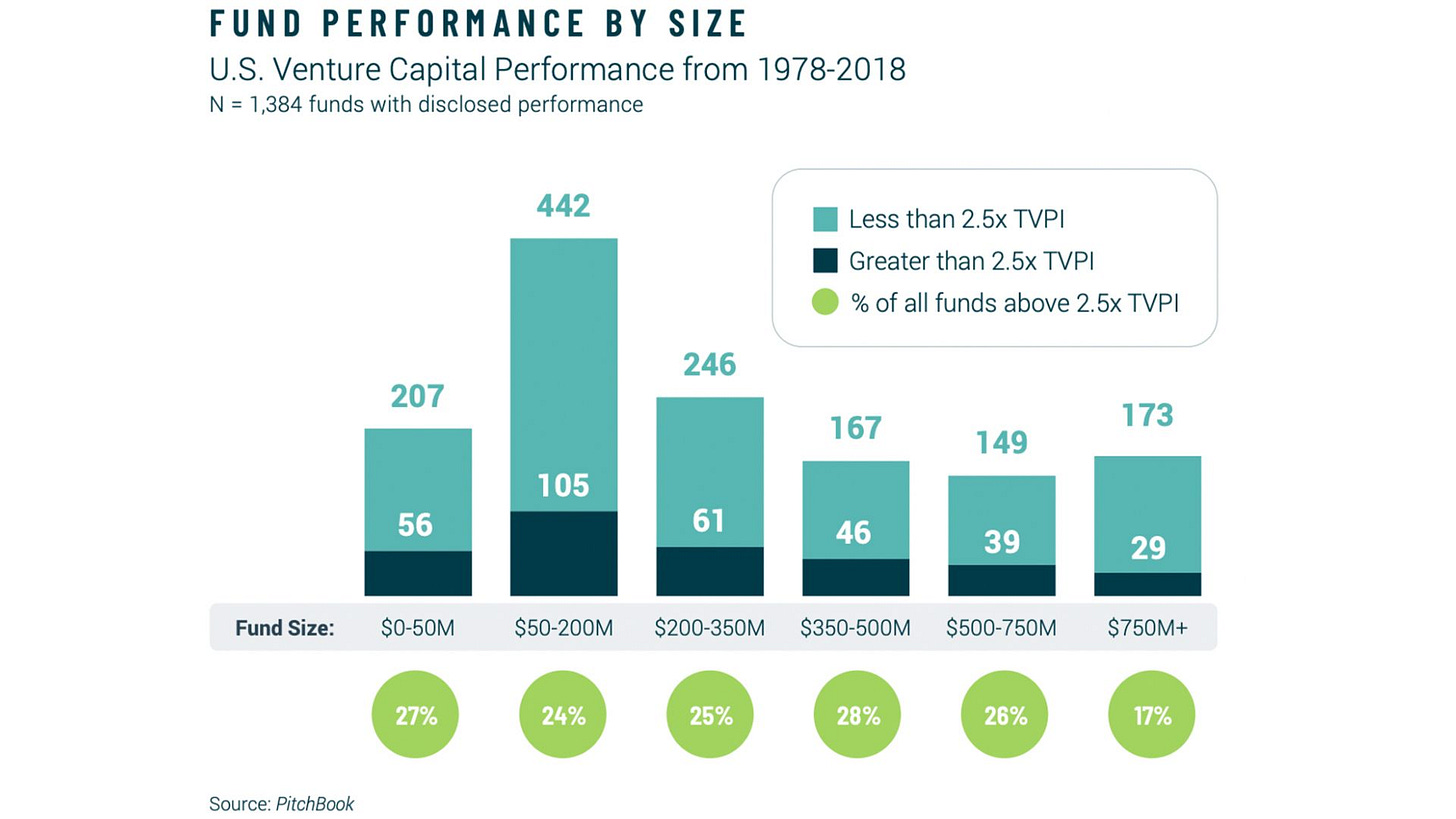

The data shows that smaller funds outperform. A recent study from PitchBook and Sante Ventures found that venture funds smaller than $350M are 50% more likely to generate a 2.5x return than funds larger than $750M.

One mentor once told me—there are a dozen ways to 10x a $30M fund; there’s only one way to 10x a $3B fund.

Running the math, a $3B fund needs to invest in two $10B companies—and own 15% of each at exit—to simply return the fund. That’s a tall task. Yet owning 15% of a single unicorn—in a portfolio of 30 companies—would 5x that $30M fund (not accounting for dilution). Or a more distributed set of outcomes—say, five companies exiting at $200M each—would also result in a 5x fund. There are many ways to slice it. You get the picture.

I expect we see a return of the disciplined, artisanal venture firm. Yet in order to see this return really happen, it needs to start with LP dollars, which have been slow to adjust. Despite smaller fund outperformance, in the first three quarters of 2023, 46.8% of US venture dollars went into funds over $500M. In 2022, that figure was 63.6%.

Venture is a power law business; one winner can return a fund many times over. Ideally you have two, three, four big winners. This is the business of not what can go wrong, but what can go right. This is a business built on optimism. It’s a natural fit for the artisanal, craftsman-like approach.

When you get it right, you get it really right. Investing in Snap’s Seed round for 15% ownership would yield a $3.6B stake at IPO with no dilution, $1.8B assuming 50% dilution. If that investment came from a $30M Seed fund, that’s a 60x fund on one investment (with full dilution). This job is about having conviction and being in early.

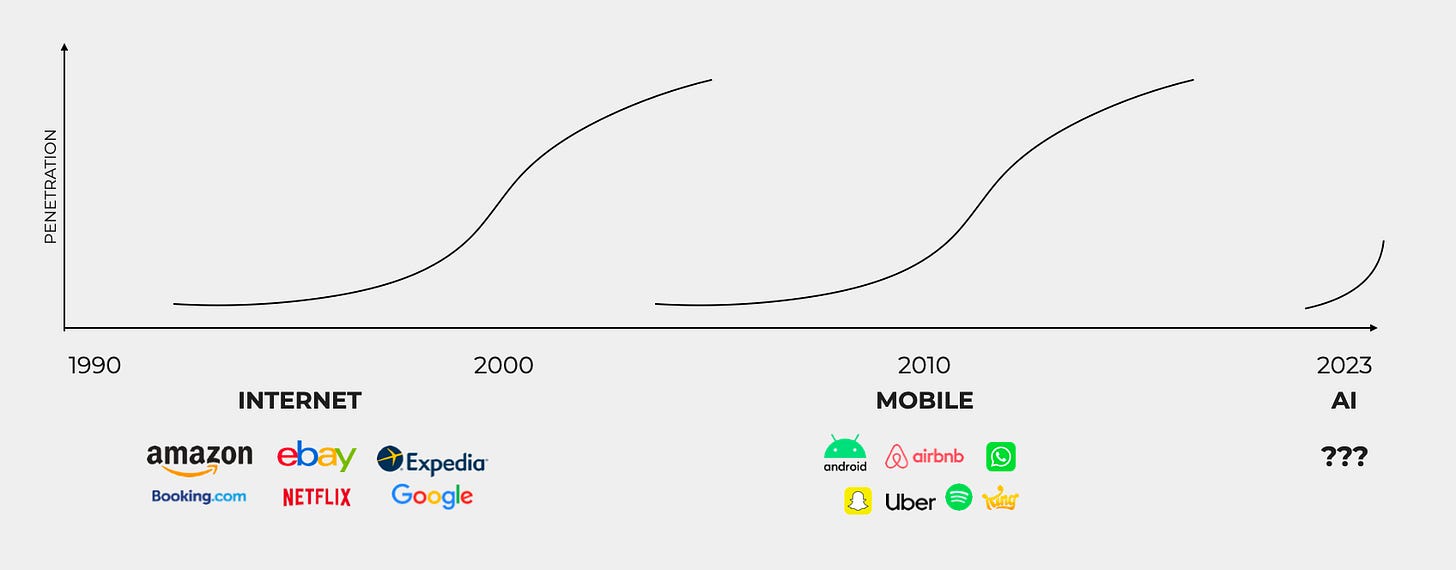

And there’s a compelling reason to think this is a good time to be investing at the early stages. We’ve seen in past technology eras that iconic companies tend to be built in the first years of a big shift. We saw this play out with the internet, which gave birth to companies like Google, Amazon, and Expedia. We saw it again with mobile, which underpinned Uber, Snap, and Android. In 2024, we’re seeing it happen again with AI.

The markets are rough right now, but we’ve also seen that film before. Looking back at the Great Recession, venture funding declined overall, but cohorts of iconic companies were born. Companies founded in the five years of 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2013 include:

These next five years—2024, 2025, 2026, 2027, 2028—may be similarly historic vintages for Seed. Venture got ahead of its skis, but it’s recovering. The asset managers will continue to amass capital and will resemble private equity. The artisanal players will rise up and reclaim the origin ethos of venture.

Sources & Additional Reading

The Economic Impact of Venture Capital: Evidence from Public Companies | Gornall & Strebulaev

I will never look at JC Penney the same—read Everett Randle’s 2021 piece

Scaling Through Chaos | Index

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: