Clicks & Clout: How We Seek Status In the Digital Age

Why Culture Revolves Around Status, and What That Means for Technology

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 60,000 weekly readers by subscribing here:

Clicks & Clout: How We Seek Status In the Digital Age

You can learn a lot about human culture through car ads.

E.B. White once wrote, “By reading automobile ads, you’d think the primary function of the automobile is to carry its owner into a higher social strata.”

Cars may be the clearest example of how consumerism revolves around status. When the automobile exploded in the mid-20th century, different makes and models emerged for different demographics. Ford and Chevy were for the working class. Dodge and Pontiac were for the middle class. Buicks were for the upper-middle-class, and business executives cruised into reserved parking spots in Cadillacs.

Car adverts plainly communicate what associations you’ll achieve by purchasing that brand. Here’s a 1952 ad for a Jaguar that clearly insinuates that owning a Jaguar = increased sex appeal:

A Ford will get you to your destination just as reliably as a Jaguar. But humans are social animals, and we care about our rank in the social hierarchy. The Jaguar might earn you more praise, admiration, and even sexual desire along the drive. That said, the increased status from the Jaguar will run you an extra ~$60K in today’s market.

Life, put simply, is all about status. I recently read W. David Marx’s book Status and Culture—thanks Bryce Ferguson for the rec—and that fact was my clear takeaway. The book subtly changed how I look at the world; when you start to pay attention, status dictates nearly everything in our lives.

In the book, Marx argues that:

There is no human society without culture, and

There is no culture without status.

I read Status and Culture back-to-back with Jonathan Haidt’s new book, The Anxious Generation, and the two books feed off one another in interesting ways. Haidt’s book contends that Millennials and Gen Zs are in the midst of a mental health crisis stemming from the rise of smartphones and social media. In other words, a mental health crisis stemming from 24/7 connectivity and 24/7 comparison.

Haidt leans heavily on the work of psychologist Jean Twenge to make his point. Last spring’s 10 Charts That Capture How the World Is Changing featured the below visual from Twenge’s 2020 paper, “Increases in Depression, Self-Harm, and Suicide Among U.S. Adolescents After 2012 and Links to Technology Use.” This chart looks at measures of suicide, self-poisoning, and depression among U.S. girls ages 12 through 15:

We see a sharp early 2010s increase, and while causation and correlation are always tricky to parse, the increase coincides with the rise of smartphones. Here’s a chart tracking smartphone and social media adoption:

Haidt argues that the constant comparison of social media—the never-ending jockeying for status—has led to an explosion in depression and anxiety. Reading Haidt’s book alongside Marx’s, the through-line is clear: the meaning of status and the pursuit of status have both changed in a technology-first world. We’re all rats in a giant, ongoing lab experiment testing how digital status-seeking influences human culture.

The goal of this week’s Digital Native is to explore key arguments of each author, then draw conclusions about what status means in a 2024 cyber-centric world.

This piece will be more cultural commentary than startup analysis, but that’s okay; we’ve been heavy on the latter lately, and cultural shifts often get overlooked in favor of technological shifts. Both are important. Our new definition of status has massive ripple effects—on what products we use, on what companies succeed, on what behaviors take shape. Understanding status helps us understand culture and predict what comes next in business and technology.

We’ll start with an overview of how status emerges in a society, then dig into modern-day status in a tech-first world:

Setting the Stage: Status Is All About Conventions

Status in a Digital World

Quantifiable

Comparison, Supercharged

Transient

Fragmented

New vs. Old

Status & Tech Products: The Elusiveness of “Cool”

Where Do We Go From Here?

Let’s dive in.

Setting the Stage: Status Is All About Conventions

Conventions are the building blocks of culture.

A convention occurs when humans choose an arbitrary practice over an equally valid alternative. The key word here is arbitrary.

Take black tie as an example. There’s no reason that men need to dress like penguins and put bows around their necks at formal events; surely a wedding would be just as functional in t-shirts and slacks. But black tie is a convention because it’s a chosen practice that becomes imbued with meaning. Show up to a wedding in a t-shirt, and you’ll be communicating that you don’t have the knowledge of what black tie means, a social faux pas that will dock you a few notches in the social ranking.

Conventions are a close cousin of social constructs, which were the focus of 2022’s piece This Is Water. That piece used the example of gendered colors. Today we associate pink with girls and blue with boys, but it used to be the other way around.

A 1918 trade publication wrote that, because pink is derived from red, “Pink is for the boys, and blue for the girls. The reason is that pink, being a more decided and stronger color, is more suitable for the boy, while blue, which is more delicate and dainty, is prettier for the girl.”

Only in the 1950s did a series of events shift pink to being “a girl’s color”—Mamie Eisenhower, the newly-minted first lady, wearing a pink ballgown to her inaugural ball; Marilyn Monroe wearing a pink strapless dress in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes; Jackie O wearing a pink Chanel suit the day JFK was assassinated. Department stores began to market pink aggressively to young girls, and less than 100 years later the convention is burrowed deep in our culture.

For added measure on how arbitrary gender norms are, here’s a photo of Franklin D. Roosevelt in a dress—a common outfit for boys during his childhood:

Even norms that we might think have a biological basis are actually manmade conventions. There are plenty of fascinating examples from Status and Culture.

One that stuck out to me: teeth. It might seem like we’d be naturally attracted to white teeth. Aren’t they a biological sign of health? But in both ancient China and ancient Japan, blackened teeth were a symbol of status; as a result, men found themselves more attracted to women with black teeth. (Teeth were blackened by soaking iron fillings in tea or sake, and blackened teeth were believed to differentiate humans from animals, marking a symbol of maturity and beauty.)

To take an even more extreme example (warning, it’s a bit graphic), we might think that humans would always recoil from the smell of rotting flesh. We naturally do; there’s a biological reason, protecting us from sickness and infection. But in ancient China, foot-binding was considered a sign of beauty. As a result, the smell of rotting flesh on a woman’s feet—as her bound feet began to decay—became a smell associated with status. Men found themselves attracted to the scent; the social convention trumped the biological impulse.

Clearly, conventions are strong—they can counteract natural forces. And conventions can persist for generations.

Galician Jews of Ukraine grew up by sugar factories. As a result, they came to enjoy sugary and sweet Gefilte fish. Today, centuries later, Galician Jews still prefer sugary Gefilte fish. American Jews, meanwhile, are largely descended from Jews who preferred saltier, less sweet dishes. You’ll still hear American Jewish grandmothers complain about “those Galician Jews who put sugar in everything.”

Conventions matter because they collect meanings and associations. They also matter because they determine conformity vs. non-conformity. Humans, as social creatures, want to belong.

Sometimes conformity is strong enough to drive dangerous behaviors. Women used to wear petticoats as a signifier of beauty and status. Yet petticoats were quite dangerous: because the garment extended so far from the body, it had a nasty little habit of catching on fire. Oops.

Over 3,000 women are known to have been burned alive by their petticoat. Yet the convention continued—achieving status and conformity was worth the risk.

Status in a Digital World

What are the conventions in a digital world?

We’re living in an interesting moment: culture has arguably changed more in the last 30 years than in any three decade span in history. Technology supercharged the pace of social change. The internet and smartphones drove change over the last quarter-century, and AI will drive change over the next quarter-century.

Digital status differs in a few key ways.

Quantifiable

One obvious shift is our newfound ability to quantify status.

Status used to be more amorphous, only visible in the physical world: “Did you see Tom is driving a Porsche?” Now we can measure status in followers, comments, likes, retweets. Status signifiers used to be luxury products; now, they’re proof of expensive lifestyles. The new Coach bag is an Instagram pic from Coachella.

Black Mirror’s “Nosedive” episode—in which people rate each other with a public social score—hits close to home. For many people, worth has become associated with online markers of status.

Quantified status also drives entire industries. Influencer marketing is a $24B market growing quickly. The industry is built on status associations. We see this clearly in the 2010s rise of “the lifestyle influencer”—lifestyles are the most obvious markers of status, and the influencer economy is built on aspiration.

This isn’t a bad thing; societies have always looked to tastemakers. In many ways, this is simply an extension of 20th Century TV and magazines, just for the long tail. Any enterprising creator can build a business as a curator of products, monetizing her influence. Savvy businesses underpin this new economy. Flagship, one of my portfolio companies at Daybreak, allows anyone with a community to launch their own boutique storefront that showcases their favorite products. They earn ~20% of sales in exchange for directing shoppers to brands through discovery-driven commerce.

This is a modern re-architecture of the broken affiliate industry, built for a world in which millions of people earn a living as online tastemakers.

The internet takes existing offline behaviors—we’ve always looked to friends, neighbors, and celebrities for advice and shopping recommendations—and brings it online with infinite distribution and zero marginal costs.

Comparison, Supercharged

Studies have shown that the neighbors of lottery winners end up buying fancier cars. That fact tells us a lot about human nature.

In today’s world, we have those same impulses, multiplied by everyone we follow online. Clearly, this hurts our mental health (we’ll get back to Haidt in a bit). I often thing of the opening lyrics from Olivia Rodrigo’s song “jealousy, jealousy”—

I kinda wanna throw my phone across the room

’Cause all I see are girls too good to be true

With paper-white teeth and perfect bodies

Wish I didn’t care

Online, we’re all peacocking for each other 🦚

The internet brought offline comparison online. In the 70s or 80s, we might only compare our careers to peers at our 10-year college reunions. “Oh, I just learned Bob made VP at Goldman Sachs. Wow, I feel like a loser.” The next day, you forget all about it. Today, of course, we’re bombarded with that kind of comparison daily on LinkedIn.

The audience for status-seeking behaviors is larger. Back in the day, you showed off your immaculate tastes with a perfectly-crafted dorm room wall.

Today, you craft your Pinterest page in an effort to show off for followers—or anyone really—and to mark success with quantifiable metrics.

Humans are naturals at this sort of thing; Pinterest has 498M monthly active users and did $3.1B in revenue last year.

Transient

One-hit wonders used to be memorable. We can all probably still dance the Macarena at a wedding, and a certainly generation looks back fondly on the pet rock phenomenon. Those events were huge and had staying power in our minds.

Now, cultural tides come and go so rapidly that we barely have time to register them. A couple years ago, JPEGs of unimpressed monkeys were going for millions of dollars—a bubble driven by status. This year, people are clamoring for Stanley water bottles, an unexpected and somewhat hilarious marker of status. (January’s Water Bottles and Lessons in Viral Growth goes into more depth on that phenomenon.)

Culture moves fast.

I often think of the Noah Smith quote: “Fifteen years ago, the internet was an escape from the real world. Now, the real world is an escape from the internet.”

In the startup world, we see this play out in startups that rise and fall quickly. The best companies are smart in nailing retention before pursuing growth, building out feature sets and re-engagement loops that prevent being a flash in the pan.

Fragmented

In 1960, 20% of all Americans watched the most popular show on TV, Gunsmoke. In 2020, only 3.8% of Americans watched the most popular show on TV, NCIS.

Culture has fragmented over the past few decades, and that fragmentation is about to accelerate. The internet broke open distribution; generative AI is set to break open creation. Both grease the wheels of cultural production. In addition to Hollywood films and network TV shows, we get 30,000 hours of video uploaded to YouTube each minute and 49,000 new songs uploaded to Spotify every day. What happens when anyone can generate high-quality video or music in seconds? Culture splinters even further.

Here’s a stunning stat: more than 39,000 accounts on TikTok now have at least 1M followers. This creates “niche fame” where within a specific following, a creator may be a rockstar, but more broadly, that same creator may be completely unknown.

Status has always involved pursuing status within your community. The study about neighbors of lottery winners buying fancy cars shows that we care about status within our neighborhood. One way that status has changed online is that we’re all pursuing status in our niche online communities. Maybe you want status on tech Twitter, so you post long threads about startups; maybe you want status within your Grand Theft Auto Discord server, so you pay up for Nitro; maybe you want status in a Reddit anime subculture, so you become a mod. As culture fragments, we seek status in more specific and personalized places.

New vs. Old

Old money has always thumbed its nose at new money.

In behavioral psychology, a “patina” is a show of status accrued over time. Your grandmother’s Birkin might hold more status than a newly-bought Birkin, because it displays generational wealth. It’s a patina. Look at the Royal Family in Britain and you’ll see patinas everywhere. Look at Drake’s $100M Toronto mansion and you’ll see a garish display of “new money.”

The same markers of new vs. old translate to the digital world. Take this screenshot of Mark Zuckerberg’s Instagram:

There are two markers of status here.

The first is the handle “zuck” which suggests an early user of a platform. If your Instagram handle is “david” or “emily,” you have social capital on the platform. The second marker is the “@1,” which denotes Zuckerberg as the first user of Threads. In a savvy effort to get people to sign up for Threads, the Instagram team displayed what number user you were in your Instagram bio; clearly, lower numbers were coveted.

When we start looking, we see patinas everywhere online. Because everything is more quantifiable and traceable in a digital realm, markers of long-held status are a smart way to reward early believers and power users.

Status & Tech Products: The Elusiveness of “Cool”

For its first couple of years, the Segway was…cool.

The product had a lot of hype. Its inventor, Dean Kamen, famously said: “The Segway will be to the car what the car was to the horse and buggy.” Steve Jobs piled on, predicting, “It will be as big a deal as the PC.”

But not long after its 2001 launch, the product began to sputter. Part of that reason: riding a Segway just couldn’t evoke coolness. In other words, riding a Segway dinged you a bit in the status hierarchy.

Mass media began to parody Segways: in Arrested Development, Gob Bluth looks ridiculous riding around on his Segway; Paul Blart: Mall Cop featured an overweight mall cop patrolling the mall on his two-wheeled device.

When it comes to products, it’s crucial to capture the cool factor.

Jobs did this with the iPod and iPhone, with combined sleek product design with sleek marketing campaigns.

Part of the Segway’s problem was its design. Jobs himself remarked, “Its shape is not innovative, it’s not elegant, it doesn't feel anthropomorphic.” (Those were Job’s three design mantras.) He added, “You have this incredibly innovative machine but it looks very traditional.” Few words were more damning to Jobs than traditional.

This will be an interesting challenge for the Vision Pro.

How do you make a clunky pair of ski googles look cool? People are already being mocked and meme-d for wearing their Vision Pro in public. An uphill battle for the device’s successful isn’t its functionality, but its cool factor.

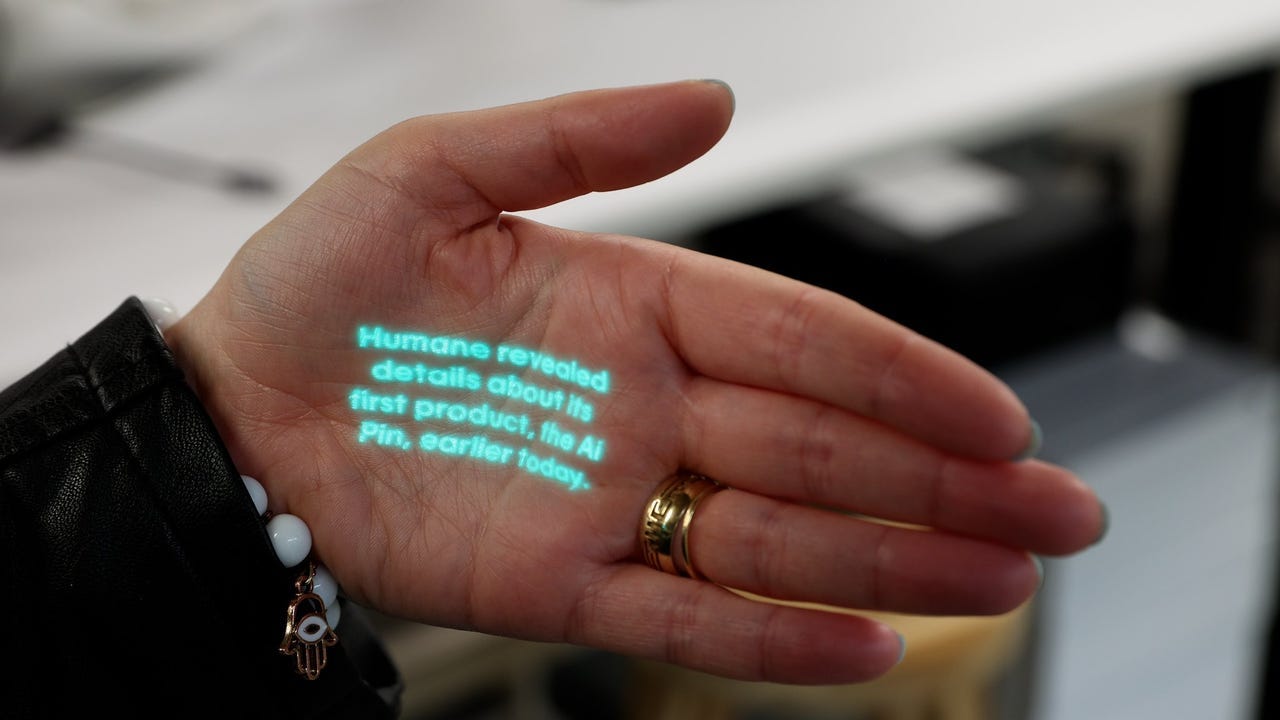

One of my 24 predictions for 2024 back in December was Humane’s AI Pin flopping.

From that piece:

I think Humane will be a tremendous flop.

The thing is: people like screens. The way we interact with content has been through screens for a long, long time. Films appeared on big screens across the country 100 years ago. Then TVs shrunk down screens into our living rooms. Computers made screens even more portable and accessible, and mobile phones then did the same.

I don’t think Humane’s design is the right one. And beyond the wrong product design, the Pin is orthogonal to today’s culture. Most people don’t want an AI device listening to them. You can imagine a scenario: you’re excited to gossip with your friend, but they’re wearing their Humane Pin. All of a sudden, you’re paranoid and won’t speak freely. I expect Humane—and related hardware plays—will bear the brunt of AI backlash.

Humane’s AI Pin to go more the direction of Google Glass than the iPhone.

Humane’s downfall now feels inevitable. MKBHD, the most influential tech product reviewer on the planet, had a damning review last week:

The product has been criticized for its poor functionality. But I think another reason it will fail is its lack of “coolness.” It hasn’t captured the public imagination.

The best companies are cool. You need a great product, of course; that’s table-stakes. But beyond that, savvy startup craft brands that become associated with status. This is even true in enterprise. Figma always had a quirky, playful ethos that was a refreshing contrast to large-scale enterprise software. Notion has been elegant and gorgeous from Day 1. Ramp took a boring category—corporate cards and spend management—and built the cool, sleek antithesis to American Express’s blandness.

Good design and good branding are almost always worth paying up for. They help companies capture the cool factor and drive status for the customer.

Digital Evolutions of Status: Where Do We Go From Here?

One interesting thing about status: what we consider “high status” can change dramatically.

It used to be high status to be overweight. Being plump signified that you had ready access to food, and thus ready access to money. But once potato farming and mass food production ensured that nearly everyone could get enough calories, the norm changed. The signifier of status became being thin, showing that you have the time to exercise and eat healthily. Rail-thin models papered magazine covers in the 90s.

We see status evolutions already happening online. It used to be high status to have a lot of followers. Now, many people view it as a “green flag” if someone isn’t even on social media. I expect we’ll see more of that, alongside Gen Z’s popularization of “dumb phones” (non-internet-connected devices) and a backlash to online peacocking.

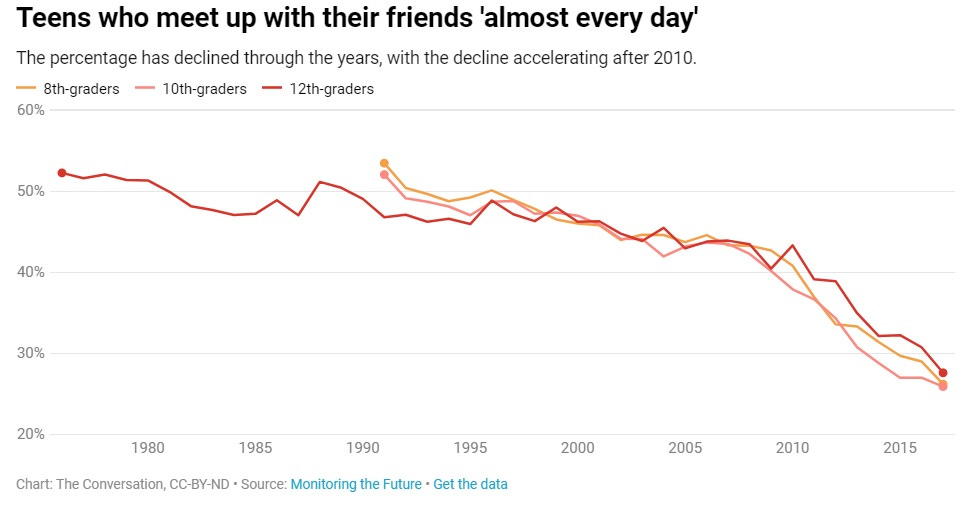

Haidt’s argument is that we’re all anxious because we’re all online, and that this is particularly detrimental for younger people:

He champions a return to play-based childhood, rather than phone-based childhood, encouraging more in-person, analog interactions at a time when those have dropped precipitously. This is good in theory, but will be hard to put into practice.

It makes sense that constant comparison makes us unhappy. I think back to a study I read a few years ago. When passengers board an airplane and walk through first-class on their way to their seats, passengers are then more likely to engage in acts of air rage and aggression than when they board from the middle of the plane. Subtle reminders of our lower status make us angry. Online, we get those reminders all the time.

Many people have suggested we remove forms of status in our culture. That’s unrealistic. All human cultures create status hierarchies; we’re very, very good at it. To return to the example of teeth, a woman named Mala Young once remarked: “As soon as it became possible for a slice of society to have good teeth, it became possible for them to humiliate the rest of society for having bad teeth. Smiling became a privilege of the rich.” As a species, we’re uniquely adept at taking any small advantage and turning it into a status marker.

It’ll be interesting to see how digital status evolves with AI. I expect that in a few years, it might be higher-status to create something sans generative AI. “Oh wow, is that movie analog?” Creating something the old-fashioned way may become a flex—a signal that you have more skill or more time. I expect blatant displays of online status-seeking will become cringe (they already are), and that eschewing technology altogether will become a marker of status.

Every choice we make is a statement on status—even if the statement is that we (supposedly) don’t care about status. A billionaire tech founder wearing a hoodie communicates, “I’m rich and powerful, so I don’t need to dress up.” Margot Robbie not having an Instagram account communicates, “I’m a big enough movie star that I don’t need social media followers.” I think back to Meryl Streep’s “Cerulean Monologue” in The Devil Wears Prada: even if you don’t think you’re a participant in the status games, you are.

We all are.

Sources & Additional Materials

Check out Status and Culture by W. David Marx—it’s a great read

Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation is a good read on how smartphones and social media have led to a mental health crisis

Eugene Wei’s Status-as-a-Service from 2019 is a classic read about how we’re all status-seeking monkeys

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: