Water Bottles & Lessons in Viral Growth

+ Five Hot Takes on Startup Distribution

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 55,000+ weekly readers by subscribing here:

Water Bottles & Lessons in Viral Growth

Gen Z’s most-coveted product of 2024 is…a water bottle?

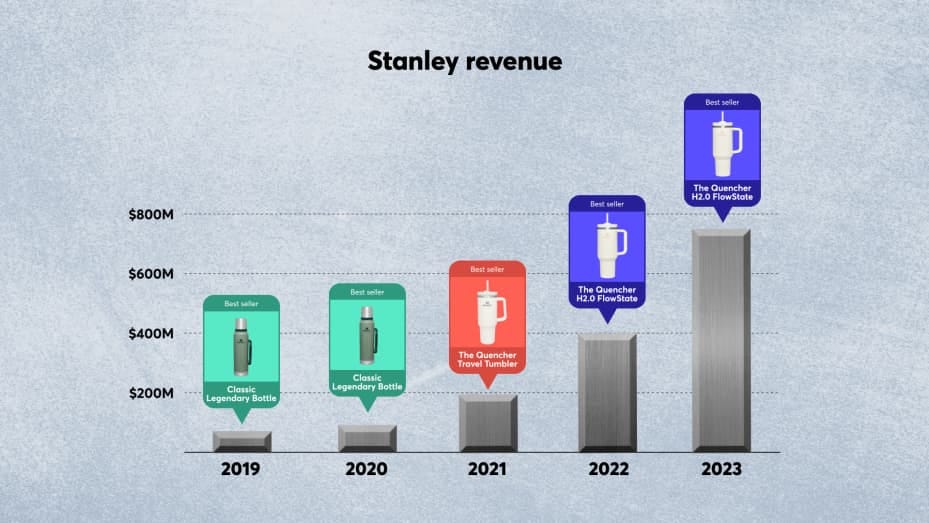

Stanley, the brand behind the now-ubiquitous Stanley water bottles (trust me: you’ll start seeing them everywhere), is a 111-year-old company that’s been on a tear the past few years: sales have grown 10x from $70M in 2019 to $750M (!) in 2023. Each new launch sells out rapidly, and Stanley’s TikTok hashtag has amassed 700M views.

What happened exactly? Stanley offers a good case study in savvy modern marketing.

To back up, Stanley was founded in 1913 by William Stanley, who actually patented the steel vacuum-seal bottle. For a hundred years, the company marketed itself to men, and particularly to outdoorsy men—campers, fishermen, hikers 🏕️🎣🥾 The product ethos was imbued with a certain…machismo; in 2012, Stanley’s marketing still mentioned that its products resonated with “a 30-year-career veteran policeman” and “a retired Army soldier.”

Fast forward a decade, and this is the company’s homepage:

It all traces back to a group of moms in Utah.

Linley Hutchinson, Ashlee LeSueur, and Taylor Cannon are the founders of The Buy Guide, an online shopping blog and Instagram account started in 2017. Ashlee LeSueur happened upon the Stanley Quencher at a local store in 2019, and immediately fell in love with it. The Quencher was a lesser-known Stanley SKU at the time, with a handle and a tapered base to fit into a cup holder. The Buy Guide women thought it was perfect for an on-the-go mom.

They also thought the product was woefully under-marketed and under-appreciated.

They reached out to Stanley to tell them their thoughts, but the company wouldn’t listen. So the women took matters into their own hands: they bought 10,000 cups wholesale and set up a Shopify store for their community. The first 5,000 cups sold out in four days; the second 5,000 cups sold out in an hour. In Taylor Cannon’s words: “It blew [the Stanley executives’] minds. They couldn’t believe how quickly we sold through our cups.”

Influencers, Community, & Product Feedback

The Buy Guide women sent a free Stanley Quencher to Emily Maynard of Bachelor fame after she gave birth. (As the women put it: “There is no thirst like nursing mom thirst!”) Maynard shared the Stanley on her Instagram Stories, which led to an inflection in growth. Using this as a datapoint, The Buy Guide women convinced executives at Stanley to launch an affiliate program, which they did. Stanley had never had a formal influencer strategy, but they began to invest in one.

To Stanley’s credit, they also began to listen to the three women for product feedback. The Buy Guide trio told Stanley that women would want the Stanley as an accessory, and that the company should make bottles with pastel colors. As the women put it on their site:

“When we first began talking with the Stanley team, we suggested daily use items that look as beautiful on kitchen countertops as they do at a campsite would not only make our target market happy, but would be a lucrative move for their business.”

In 2020 and 2021, Stanley released over a dozen new color variations—each one quickly selling out. Sales more than doubled in 2021 to $194M.

Around the same time, Stanley hired a new President—Terence Reilly, who came from the Chief Marketing Officer role at Crocs. Reilly borrowed heavily from the Crocs playbook; Crocs had also reinvented itself in recent years using savvy merchandising and marketing tactics.

In 2021—19 years into the company’s life—Crocs revenue grew 67% (!) to $2.3B. Profit margins in 2021 improved from 22% to 31%. This followed nearly a decade of flat sales and stagnant margins.

Some of Croc’s 2021 growth stemmed from a COVID-induced boom in comfort wear, sure, but much of it came from renewed focus. In 2020-2021, Crocs trimmed its product selection by 30-40%, which helped the company improve margins and refocus marketing efforts on its iconic clogs. Keep the main thing clog the main thing clog. Crocs also announced that it would close all 558 retail stores, shifting entirely to e-commerce.

Reilly brought similar ideas to Stanley. The company made the Quencher its marquee product, and marketed the product as an item of self-expression. Crocs had seen success with Jibbitz, little charms that let people customize their Crocs. Jibbitz made Crocs a vehicle for showcasing personality and uniqueness.

Stanley followed a similar playbook with dozens of variations in bright greens and blues and reds. As Reilly put it on CNBC: “We see all the time that [our customer] wants her Quencher to match her fit, her nail polish, her car, her mood, her kitchen. We’re serving her where she wants the product.”

Collabs & Drops

Crocs had also seen success with collaborations. The goal had been to inject coolness into the brand through affiliation. There were partnerships with Justin Bieber and Post Malone, with Diplo and Balenciaga, with Hidden Valley Ranch and KFC. Those collabs played a key role in turning Crocs from 2010s punchline into something of a 2020s fashion statement.

Stanley followed the same playbook, leaning heavily into collabs with brands like Olay and Starbucks. Reilly also borrowed from “drop culture,” popularized in the sneaker and streetwear worlds. By constraining supply, each new Stanley launch became an event; consumers scrambled to get their hands on a product. After the collab with Starbucks, a red Quencher was resold on eBay for hundreds of dollars the same day it dropped.

Internet Virality

A final thing Stanley did well: invest heavily in social.

Stanley hired a dedicated TikTok agency. It began to develop a brand identity through its content. And when viral moments came, it seized them.

Stanley’s biggest viral moment came last fall. A woman’s car burned down but, shockingly, her Stanley Quencher survived the blaze. In fact, the water bottle still had ice in it. The woman’s TikTok about the incident got 94M views. A brand couldn’t ask for better free advertising.

To Stanley’s credit, they quickly seized the moment. Within a day, Reilly replied to the woman’s video with an announcement: Stanley would be buying her a new car for free.

The stunt was savvy marketing—the reply video has 54M views, 6.9M likes, and 68K comments. Even the most conservative CPM math puts the company well in the black on paid marketing ROI.

In 2024, Distribution Is King

Stanley is a good reminder that an excellent product is tablestakes, but that distribution is king. Otherwise, a good product just sits on the shelves.

There are a number of lessons from Stanley’s success:

Pay attention to how people are using your product, and rely on your customers for feedback that informs the roadmap.

Develop an influencer strategy and a social strategy.

When viral moments come, move fast and capitalize on them.

The importance of distribution extends to the startup world. In fact, it matters most in the startup world. As the old adage goes: “The battle between every startup and the incumbent comes down to whether the startup gets distribution before the incumbent gets innovation.”

My view is that in 2024, distribution will only become more critical to startups. This is because it’s never been easier to build a product, but it’s never been harder to grow.

Tools like AWS, Stripe, Shopify, Twilio, and Langchain—among many others—offer Lego-like building blocks with which companies can quickly spin up products. These tools are more accessible and affordable than ever before, unlocking startup creation.

Yet growth is tricky. For one, customer acquisition costs are on the rise. Meta, Google, and now Amazon have a stranglehold on the digital advertising market, and even digital real estate is finite. It’s simple supply and demand. Privacy changes, meanwhile—most notably Apple’s App Tracking Transparency—have eroded direct response effectiveness. A generation of companies built in the 2010s—DTC brands and consumer subscription businesses, for instance—simply wouldn’t work in 2024. Paid marketing is both (1) more expensive and (2) less measurable.

Add to this the scale of incumbents, who wield built-in distribution. How can a startup outmaneuver Big Tech players with billions of users?

Startup success is predicated on hitting escape velocity—achieving breakout, compounding growth. This requires scalable, efficient distribution, which is becoming more challenging to unlock. The rest of this piece shares five “hot takes” I have on distribution.

1) Brand is consistently undervalued—including in B2B.

What is a brand? A brand is a crystal clear definition of why your business matters. Why should people choose you? This question becomes even more pressing in a world of near-infinite choice: when there are so many options out there, why you?

I’ve always been obsessed with brand. Brand is something intangible, squishy, hard to pin down. But it’s essential to a company’s success. We wear Nikes because we want to be like LeBron and Serena; we watch Disney movies because Disney embodies great storytelling; we buy Apple products because Apple stands for innovation and product excellence.

There’s a classic debate in the startup world over whether brand is a moat. In other words, can a company’s competitive differentiation come from its brand? My view has always been yes. There are better moats than brand, sure, but brand matters. Many iconic companies (both consumer and enterprise) will always enjoy an advantage because of the strength of their brands—and that advantage compounds, with the strongest brands enjoying name recognition that drives strong cash flows, which can then be plowed back into further growing the brand.

One of my long-held views: nearly every company consistently undervalues brand.

This carries over to B2B businesses too. Every company, no matter consumer or enterprise, has a buyer. That buyer, ultimately, is a person. Brand has an impact on that person’s decision-making. (As we see the “consumerization” of the enterprise, lines further blur.)

Take Ramp as an example. Ramp sought out to disrupt the corporate card market. The corporate card world is dominated by established players that are associated with status (cough, Amex, cough). Ramp needed to do something different.

Ramp’s strategy became, “Smart is the new platinum.” The founders, working with the brand agency Red Antler, realized that today’s businesspeople are less concerned with dropping the corporate card at the steak lunch, and more concerned with visibility, control, and data. They want to spend less and they want to spend more intelligently. Flagrant spending is out; smart, sustainable growth is in. Ramp’s brand strategy leaned into these insights.

I dug deeper into the example of Ramp and other companies in last year’s How to Build Your Startup Brand. A favorite quote from Red Antler’s Jenna Navitsky: “Unsexy categories are the biggest opportunity to do something really interesting on brand.”

As competition heats up in 2024, brand becomes an even more important facet of distribution—one that’s often overlooked. Brand is something to invest in early, at Pre-Seed and Seed, and key brand decisions have compounding effects on customer acquisition, talent acquisition, and company culture.

2) “Boosts” are helpful, but built-in virality is the Holy Grail.

With performance marketing becoming more difficult, startups need to figure out virality. I tend to group virality into two buckets:

Built-in Virality: This is virality embedded in a company’s business model or product.

Viral Boosts: These are one-off “boosts” that drive growth, but that aren’t intrinsic to the business / product.

The analogy I think of—though somewhat silly—is Mario Kart. Built-in virality is the vehicle you select; it’s the engine, and it’s core to your business / product. Viral boosts, meanwhile, are Mario Kart’s growth boosts (for the uninitiated player, you collect coins that you can then spend on boosts to deliver speed and acceleration). Boosts are short-lived, but helpful.

Dan Hockenmaier and Lenny Rachitsky have a more in-depth racecar analogy in their Reforge course (worth checking out) but I’ll keep things simple here with just the two components.

Boosts are like Stanley’s viral moment with the car fire: that incident no doubt led to a spike in sales. But boosts can also be systematized. Last summer’s piece How Duolingo Grew Its TikTok to 6.6M Followers dug into the strategy and systems behind Duolingo’s viral TikTok, which reliably produces viral moments week after week.

While boosts are great, there’s no substitute for the engine of built-in virality. These are the product loops that drive compounding growth. Think of social features—Instagram piggybacking on your Facebook social graph or contacts list for growth, Figma asking you to invite your coworkers, or Airbnb incentivizing referrals in the early days:

Or think of growth loops that spin faster over time, like Faire’s retailer-brand referral loop:

The nice thing about internet and software products, compared to the Stanley tumbler, is that you can engineer growth loops directly into the product.

3) Design is almost always worth paying up for.

Built-in virality means building product, and the sister of product is design.

Few things are more worth investing in than good product design. Aside from a 10x founding engineer, I see a top 1% designer as the most critical early hire. Good designers are few and far between. For early-stage companies struggling to find one, good agencies exist that can devote 30-40 hours a week to your product until you find (or can afford) a good full-time designer.

Paying up for design almost always pays dividends—particularly since customers, in both consumer and enterprise, have become accustomed to intuitive, elegant, polished products. Good design is now table-stakes, and it’s worth paying for.

4) Startups shouldn’t be paid marketing heavy.

The job of a startup is to grow—fast. This is what differentiates startups from the millions of other businesses started each year. Startups are predicated on rapid, parabolic growth.

My view is that, at least in the early days, startups shouldn’t be paid marketing heavy. Yes, there are exceptions; some companies can make the LTV-to-CAC math work on paid acquisition. But those unit economics usually break down, and the best companies have some organic growth driver that supercharges breakout growth.

Again, what’s nice about technology businesses, compared to physical products businesses, is that you can engineer features that nurture organic growth.

5) The best way to grow? Make people money.

Fewer incentives are stronger than monetary incentives.

One of the best ways to get people to spread the word about your product is either to save them money or to earn them money.

Take the Faire example. Say that Rachel, the retailer behind Rachel’s Boutique, already works with a dozen brands. For every brand that Rachel refers to Faire, she gets a shopping credit. Faire also won’t take a commission on that brand-retailer relationship. The platform is designed so that everyone wins. Brands want all their retailers on the marketplace, because they benefit from managing their entire business all in one place. Retailers benefit because they get access to free returns, net-60 payment terms, and better shipping rates. Incentives turn the flywheel faster.

Many of the most successful technology companies have grown because they earn their users money. Amazon’s third-party seller network supports 10M livelihoods. Figma and Notion both have robust third-party application ecosystems; a search for Notion on Etsy shows hundreds of Notion templates for sale. Roblox developers earn payouts from users, which turns the flywheel. Even if there isn’t a natural flywheel for your business, incentivizing referrals (e.g., extra features or reduced price for [5] referred users) is a good starting point.

Final Thoughts: AI & Distribution

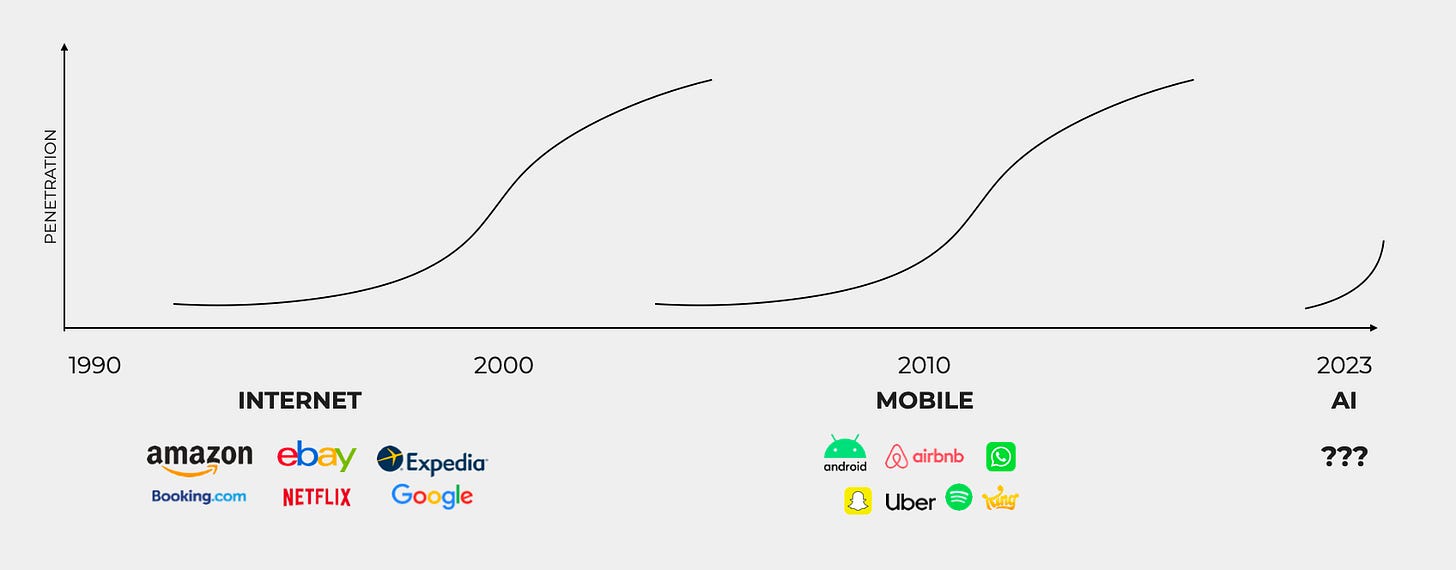

One reason that distribution will be so critical in 2024: this is the year of AI’s application layer. We’re beginning to see early apps emerge, just as we’ve seen apps emerge in prior technology epochs like mobile and internet.

In the mobile and cloud revolutions, much of the value accrued to incumbents—Apple in mobile, for instance; Amazon and Microsoft in cloud; Google in both. Yet we still saw an explosion of valuable applications built on these revolutions—market leaders that maybe should have been within the walls of Big Tech, but weren’t.

Facebook was caught flat-footed by mobile, then had to buy Instagram to keep up; Meta would be a dramatically different company today if that acquisition hadn’t gone through. Instacart and DoorDash emerged despite Amazon’s logistics dominance and expensive entry into grocery via the Whole Foods acquisition. Microsoft theoretically should have built products like Figma, Notion, or Slack to own the enterprise software suite, but it didn’t. Why? Focus wins—both on building a 10x product and nailing distribution.

In 2023, the AI stack took shape; very good open-source models have emerged that in many cases outperform closed-source models. We’re moving into the application era, and it’s going to come down to who can arrest the public’s attention through savvy growth tactics, marketing, and product virality.

The battle for distribution is on. If a 111-year-old water bottle company can suddenly become the hottest product of the year, the sky’s the limit for savvy tech companies that test new growth channels, iterate based on user feedback, and get creative with distribution.

Sources & Additional Reading

Stanley Quencher’s Viral Success | Retail Dive

How a 40-Ounce Cup Turned Stanley Into a $750M Business | CNBC

The Story of the Cup | The Buy Guide

Related Digital Native Pieces

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: