Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 55,000+ weekly readers by subscribing here:

Crazy Ideas

Poor Things—the latest film from Yorgos Lanthimos—was one of my favorite films of 2023. If you’ve seen the movie, you know that it’s incredibly, absurdly weird. If you haven’t seen it, I won’t give away any major spoilers here—only the basic premise, which is revealed in the first 20 minutes.

The film tells the story of Bella Baxter, played by Emma Stone. Bella is the creation of a mad scientist who found Bella’s pregnant, barely-breathing body after a suicide attempt and—in a crude experiment—replaced her brain with the brain of her unborn child. If you think that sounds like the makings of a wild movie, you’re right.

Poor Things follows Bella’s coming-of-age. In the early part of the film, Bella’s brain is that of a toddler; she teeters around rooms and can barely form coherent sentences. Soon, Bella is a sex-crazed adolescent who rebels by running away to Lisbon. And eventually, we see Bella mature into a grown woman.

This is all anchored by a stunning performance from Emma Stone, who traces every step of Bella’s brain development. (The performance is even more impressive given that scenes weren’t shot chronologically; Stone had to constantly switch between “infant Bella,” “adult Bella,” and so on—often within the same day of shooting.) Deservedly, Stone is the co-frontrunner for Best Actress alongside Lily Gladstone.

How is any of this relevant to startups, technology, and modern culture? Bear with me.

In Poor Things, we see Bella look at the world with fresh eyes. She questions everything. The film is, at its core, about a young woman who asks why things are the way that they are; she’s capable of imagining a world very different from her own. That’s a skill not many people have.

Questioning the world is also a valuable exercise in predicting which startups will change how we live and work. The other day, I found myself walking around New York and channeling Bella Baxter as best I could. (You know when you watch a movie and it becomes your entire personality for like six hours?) I thought about what would look odd if I were a 20th-century adult plopped into 2024 New York City.

I watched people walk while staring at their little panes of glass; I saw people wear their AirPods and get into their Ubers and grab their DoorDash orders. I then tried to imagine how these streets might look in 2034. Working backwards, you can think through what innovations and businesses will underpin the changes from 2024 to 2034.

Some of the most successful companies of this century have been built on big ideas that challenged a well-accepted norm: Uber encouraged us to share a vehicle with a stranger; Airbnb asked us to live in a stranger’s home and to invite them into ours; Facebook, and later TikTok to an even greater degree, taught us to broadcast everything to everyone around the world.

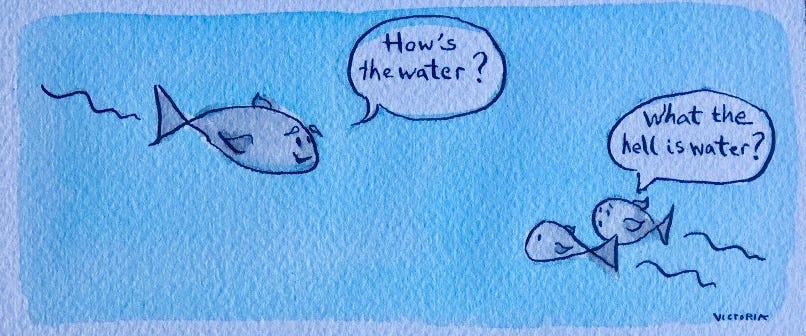

In 2022, I wrote a piece called This Is Water about social constructs. It made a similar point: some of the most radical businesses come from radical ideas that rethink society’s standards. Most of us are fish, oblivious to the water around us. The best entrepreneurs and iconoclasts, meanwhile, question the water.

When we look around, we see examples of shifting social constructs all around us. It used to be a fact of life that most knowledge workers would commute to and from an office each week; that’s no longer the case. It seems we’ve reached a steady-state office occupancy rate hovering around 50% in the post-COVID world:

Naturally, this has ripple effects—on the software we use to work; on what we do with the time once reserved for our commutes; on the businesses that relied on office workers.

Remote and hybrid work are a cultural shift. Technological shifts also have ripple effects. Think of the ways the iPhone has changed the world. To use one small example: chewing gum sales reportedly dropped after the iPhone came out, because people became distracted on their phones in grocery store checkout lines and made fewer impulse purchases.

Of course, who knows how well-corroborated this data is; causation isn’t the same thing as correlation. But it’s certainly plausible, and it’s a metaphor for bigger ways smartphones changed society. Maybe an AI device like Humane or Rabbit will have a similar impact. Rabbit sold 40,000 devices in its first four days on the market. Back in 2007, the iPhone—backed by Steve Jobs’s charisma and Apple’s marketing muscle—sold just 270,000 units in the U.S. The figure now? 2.3 billion. (I still think both Humane and Rabbit will be flops.)

The goal of this week’s Digital Native is to think through a few ways in which society might look radically different in a few years. If we squint, we can think like Bella Baxter, questioning the status quo and exploring wild ideas that could reshape the world around us.

I’ll touch on three.

The End of Subtitles?

Last week in Davos, Argentinian President Javier Milei delivered a speech to the World Economic Forum. Milei gave the talk in Spanish, but used the AI startup HeyGen to translate it to English. The result was remarkable: HeyGen accurately transcribed the talk into English, while also making Milei’s lips move so that it looks like he’s speaking English. The software maintained his mannerisms and facial expressions, and even mimicked his tone of voice.

This is pretty wild. Milei can’t speak English, but a relatively recent AI tool creates a world in which he effectively can.

Will subtitles become a remnant of the past? We joke about bad dubbing in movies—and it’s almost always better to watch a foreign film with subtitles. Technology is rendering both dubbing and subtitles moot. We’ll live in a world where Biden can deliver a speech in Mandarin, where MrBeast can hold an online meet-and-greet in Tagalog, and where you won’t even know that your favorite YouTuber—whose videos you adore—only speaks Russian in real life.

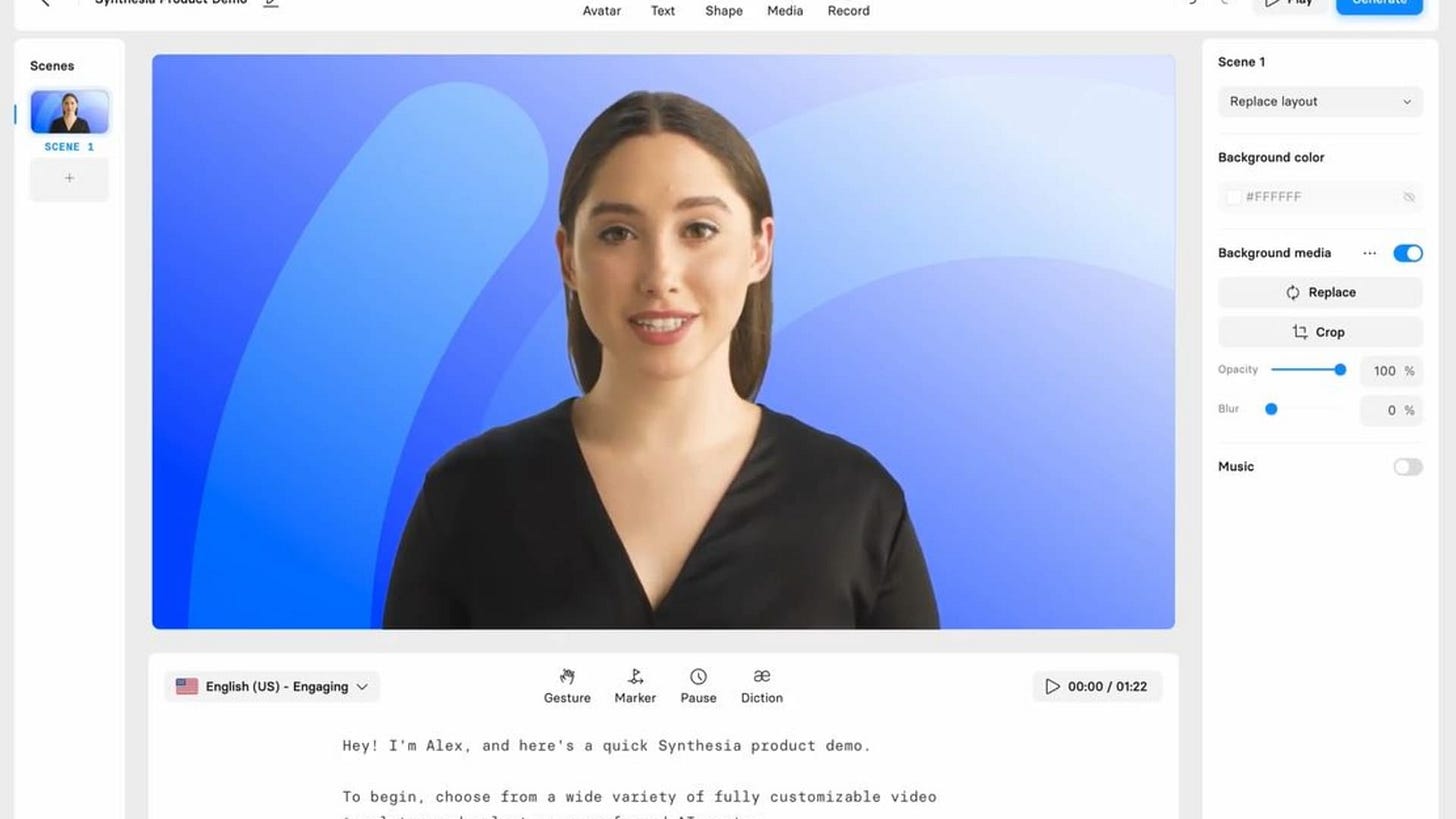

Enterprise applications here have existed for a few years; Synthesia, for example, helps companies use AI-generated avatars in videos for sales, marketing, and learning & development. The outputs are a tad uncanny valley, in my opinion, but they’re still impressive—and much more economical than paying for an expensive human.

HeyGen, meanwhile, has both consumer and enterprise uses; it’s the same software I used in a piece last year to create my own talking Pixar character (the toolset there was Midjourney + HeyGen + Eleven Labs).

The dark side will be the proliferation of deepfakes, and OpenAI already has a big plan to combat 2024 election misinformation. We’ll need tools to distinguish a “real” video from a video that uses AI to plausibly fake something. But our kids might be blown away to learn that there used to be tiny words on the screen that we had to read while watching a movie.

Immersive, Participatory, Never-Ending Stories

There’s a new museum in Las Vegas called the Arte Museum. One of the interactive exhibits, called “Night Safari,” allows guests to sketch their own animal drawings, scan their artwork, and watch as their creations become part of the exhibit, complete with movements and sound effects.

One woman drew an elephant, then watched her elephant come to life in the exhibit:

The exhibit embodies the broader arc of content, art, and stories: more creation and more participation. Think of the powerful video creation software from companies like HeyGen. It’s only a matter of time until we’re all able to participate in our favorite movies, TV shows, and games. You’ll be able to watch The Avengers starring your group chat.

This will extend to non-player characters. NPCs are the lifeblood of gaming. The 2021 action-comedy Free Guy starred Ryan Reynolds as a bank teller who discovers he’s an NPC in an MMO (massively-multiplayer online game), then teams up with a player to fight a villain. Soon, NPCs in game-worlds will be as lifelike as Reynolds’s character—living, breathing characters indistinguishable from real players. Companies like InWorld.ai are powering this, and we’re only at the tip of the iceberg. People are falling in love with AI chatbots on apps like Replika and Chai; soon they’ll be falling in love with NPCs in game-worlds. (If you read the novel Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow—one of my favorites—you’ll remember a similar plot-line.)

Realistic generative characters will become table-stakes. So will a new form of entertainment: the never-ending story.

Why should a story end when production costs are cheap and when participants in the story can steer the story? Imagine playing a video game that doesn’t render, but generates; it adapts to your gameplay, with new levels rapidly created as you go. You can’t “beat” the game like you’d beat an old console game you picked up at GameStop. It just keeps going as long as you keep playing.

This will apply to gaming first—nowadays the early adopter category in media—but the same concept will eventually make its way to film and TV. It’s been true for years in online fan-fiction communities, where stories won’t reach a conclusion as long as someone around the globe is willing to write the next chapter of Harry’s and Draco’s forbidden romance. And someone always is. (I want to see what percent of fanfic is LGBTQ+; I’d put money on it being over 30%.)

I expect to see startups build both new creative tooling and new platforms that become hubs for generative stories and gameplay. In 2034, young people might be surprised to learn that games used to have finite endings; that NPCs were half-baked side characters; and that the lines between creator and consumer weren’t so blurred that they’d become indistinguishable.

Blending the Physical and Digital

I have friends who swear that the biggest source of joy in their everyday life is…wait for it…playing Pokémon Go. They play Pokémon Go constantly while walking around New York City; it gamifies their every waking hour.

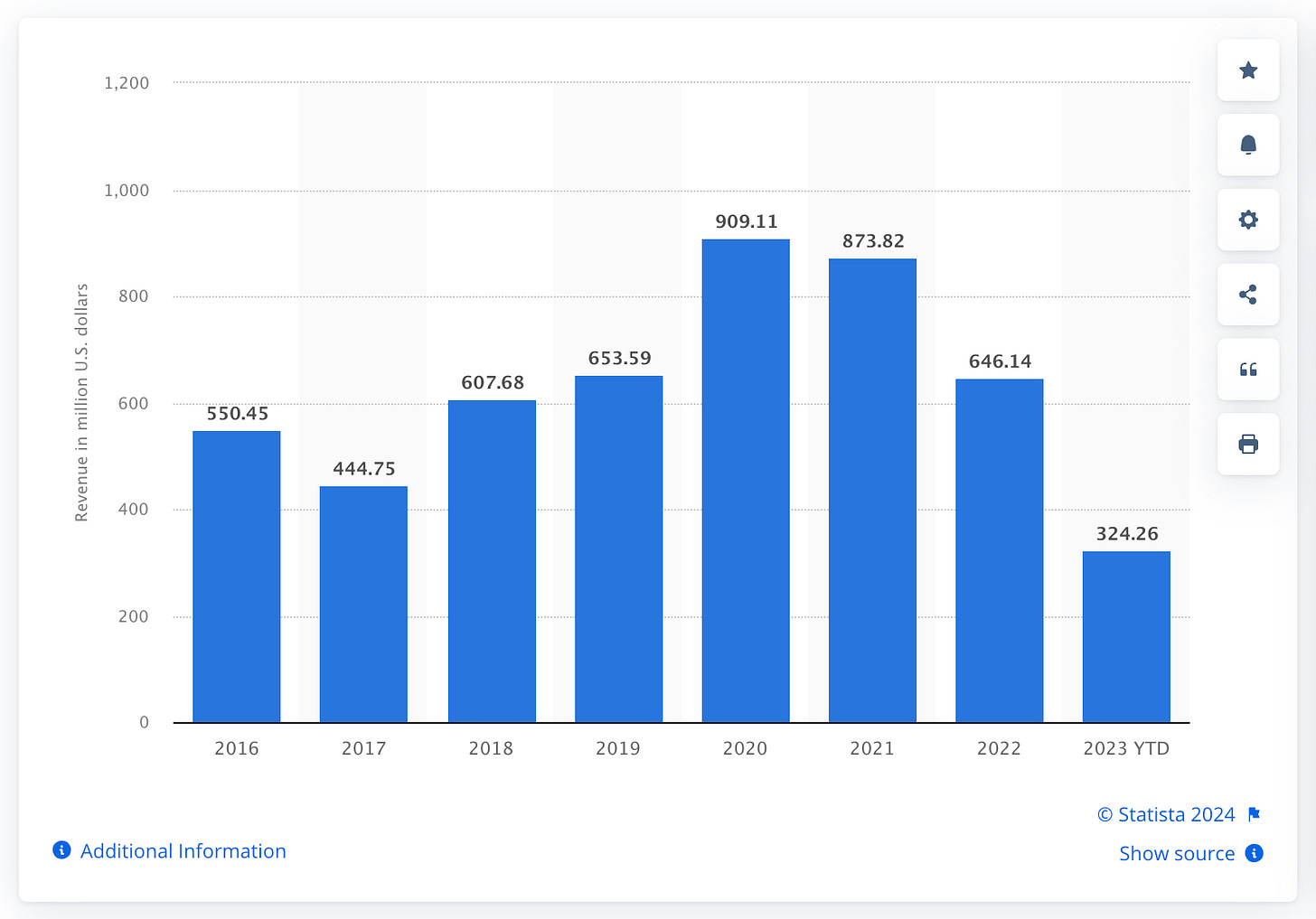

When it was released by Niantic in 2016, Pokémon Go was a sensation. It brought in over $500M in its first year. By 2021, it had grossed $5B in lifetime revenue. It’s popularity has waned in recent years, but it still remains a cash cow for Niantic, which has struggled to repeat the game’s success with successive augmented reality releases (Niantic’s Harry Potter game shut down in 2021, while its Catan game shuttered within its first year).

Almost a decade after launch (does that make you feel old?), Pokémon Go is probably still the most mainstream use case of AR. In my mind, it’s inevitable that AR will eventually be everywhere. This is the natural progression in the “always-on” digital world. The internet used to be a destination we logged into a few times a day; we told our friends “brb” when we logged off. “Brb” no longer makes sense; we’re always available. Eventually, we’ll look back, incredulous that we used to walk around staring at our tiny phone screens; the digital world will be organically overlaid on top of the physical world.

Google Maps will project walking directions on the street in front of us; Yelp will show star ratings above each restaurant; LinkedIn will put someone’s name and job title above their head at a networking event (name-tags will feel quaint).

It will probably take some time (read: many years) for this reality to be realized. But it’s inevitable. As shown in the examples above, I expect existing technology players to dominate AR applications. Why would a new AR mapping application beat out Google? Time spent with AR will outweigh time spent with VR (because AR will be everywhere) but VR will be a more valuable playing ground for new companies.

Final Thoughts

What other ways will the world look different in 2034?

For one, I think (and hope) that nuclear energy is becoming the foundation of our energy system. We’ll look back and wonder what took us so long to embrace the inevitable. I also hope, though doubt, that our education system will have changed; it makes no sense to have a post-Industrial Revolution format in the 21st Century. And maybe we’ll have self-driving cars—or, even better, cities built for people, not cars. The area in New York City devoted to street parking is equivalent to 12 Central Parks (!). Just think how else that space could be used. My friend Martin shared this image with me—once you see it, you can’t unsee it:

I also think we’ll look at vaping the way we look at cigarettes today, that alcohol will no longer be so central to socialization, and that drugs like weed, mushrooms, ketamine will gain “market share” (including in therapy). The list goes on. Maybe we’ll walk down the street in 2034 and see people wearing their mixed reality headsets while zooming around in their autonomous vehicles.

I recently saw a TikTok of the singing competition The Masked Singer, with a contestant wearing an absurd outfit and performing in front of thousands of people. Someone commented, “Imagine trying to explain this to a time-traveler from the Middle Ages.”

We can look around and ask the same question. Small changes happen gradually, but cascade into a world unrecognizable to people from just 20, 30, 40 years ago. I recently watched someone show a friend ChatGPT for the first time, and the person couldn’t believe her eyes; how she got to 2024 without knowing about ChatGPT is another question.

Channeling our inner Bella Baxter helps us look at the world around us with a fresh perspective. We can think about the steady march of innovation (intermingled with some unchanging truths about human behavior), squint our eyes, and imagine ways the future will look radically different.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: