Daybreak: Announcing Our $33M Inaugural Fund

Our Launch in Fortune + Behind-the-Scenes of Raising Daybreak Fund I

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 65,000+ weekly readers by subscribing here:

Daybreak: Announcing Our $33M Inaugural Fund

This morning, we formally announced Daybreak in Fortune. Check out the piece here, written by the terrific Allie Garfinkle.

Allie manages to work in many of our favorite Digital Native topics—AI product design, Betty Crocker cake mix, even Taylor Swift.

We’ve been building Daybreak in public since the beginning; my view has always been that venture capital is too much of a black box, and that building in public forces transparency, discipline, and clarity of thought. But we hadn’t officially announced the fund size or done a press piece until today.

This week’s Digital Native is a companion piece to the Fortune article. We’ll dig a little deeper, pulling back the curtain on the fundraising and firm-building process.

I’ve broken this piece into five parts:

The Behind-the-Scenes: Starting and Raising a Venture Capital Firm

The Strategy: Thesis-Informed, Founder-Centric

The Philosophy: Artisans, Not Asset Managers

The Math: Daybreak Portfolio Construction

The Vision: Where Daybreak Goes From Here

Let’s dive in.

The Behind-the-Scenes: Starting and Raising a Venture Capital Firm

Today’s a rough moment for venture funds. Check out this chart:

Yikes.

Why is this? Well, distributions are at the lowest point in ~15 years. LPs need distributions to get liquidity and to be able to make commitments.

Over the next few years, I expect we’ll see a washing-out of venture firms. Firms that over-raised and over-invested in the 2020-2022 boom years will find it difficult to raise subsequent funds. Even more established names are winding down. Jeff Weinstein summed it up well in this post:

The good news is: there’s light at the end of the tunnel. The IPO market will probably open later this year, and a changing of the guard at the FTC should mean acquisitions back on the table. But the past 18-24 months were the worst time for fundraising in at least a decade.

This makes life tough for emerging managers, the term for new venture capital funds like Daybreak. But it’s not all bad. When I told my mentor and Index colleague Martin that I was starting Daybreak, he said: “It’s probably the worst time in 15 years to raise a fund, but it’s probably the best time in 15 years to deploy one.” He’s right. Market downturns create a talent unlock: employees leave their companies to venture out on their own. And right now, that talent unlock is coinciding with a major technology shift (heard of AI?), which makes this a uniquely good moment for Pre-Seed and Seed.

Here’s a slide from our Daybreak fundraising deck that captured this:

I’ve written in the past about how the years 2009 to 2013 saw the dual forces of mobile and cloud power some of the best vintages ever for venture capital.

Example companies built on those shifts during that five-year span:

Mobile: Uber (2009), Lyft (2012), Instagram (2010), Snap (2011), Robinhood (2013), Coinbase (2012), WhatsApp (2009)

Cloud: Slack (2009), Airtable (2012), Stripe (2010), Plaid (2013), Snowflake (2012), Databricks (2013), Figma (2012), Notion (2012)

The 2024 to 2028 years should, hopefully, produce similar generational companies. Our recent piece How AI Will Reinvigorate Consumer Tech shared this chart:

All those “???” should yield large companies. We could do the same exercise for enterprise—agents verticalized both by industry (law, architecture, construction) and function (engineering, sales, customer success). Today is a huge moment for innovation. That’s the “why now” for Daybreak.

So mechanically, how does one go about launching a venture firm?

First, you get some great service providers. We use Cooley for legal fund formation, Aduro for fund administration, and Frank Rimerman for tax and audit. Those three firms make my life a lot easier. After setting up the fund—which means a lot of legal legwork and money—you can start fundraising.

Fundraising for a venture capital firm is a bit of a grind, especially in this market. Most “lead” checks (anchor checks) for a fund won’t be more than 10% of the fund, so it takes a while to get to know and secure anchors. At Daybreak we have five anchor-like checks, two Family Offices and three Fund of Funds. Each process typically takes many months, many meetings, and many reference calls. So fundraising takes some patience. The good news is, you can close some capital early and start deploying alongside the fundraise.

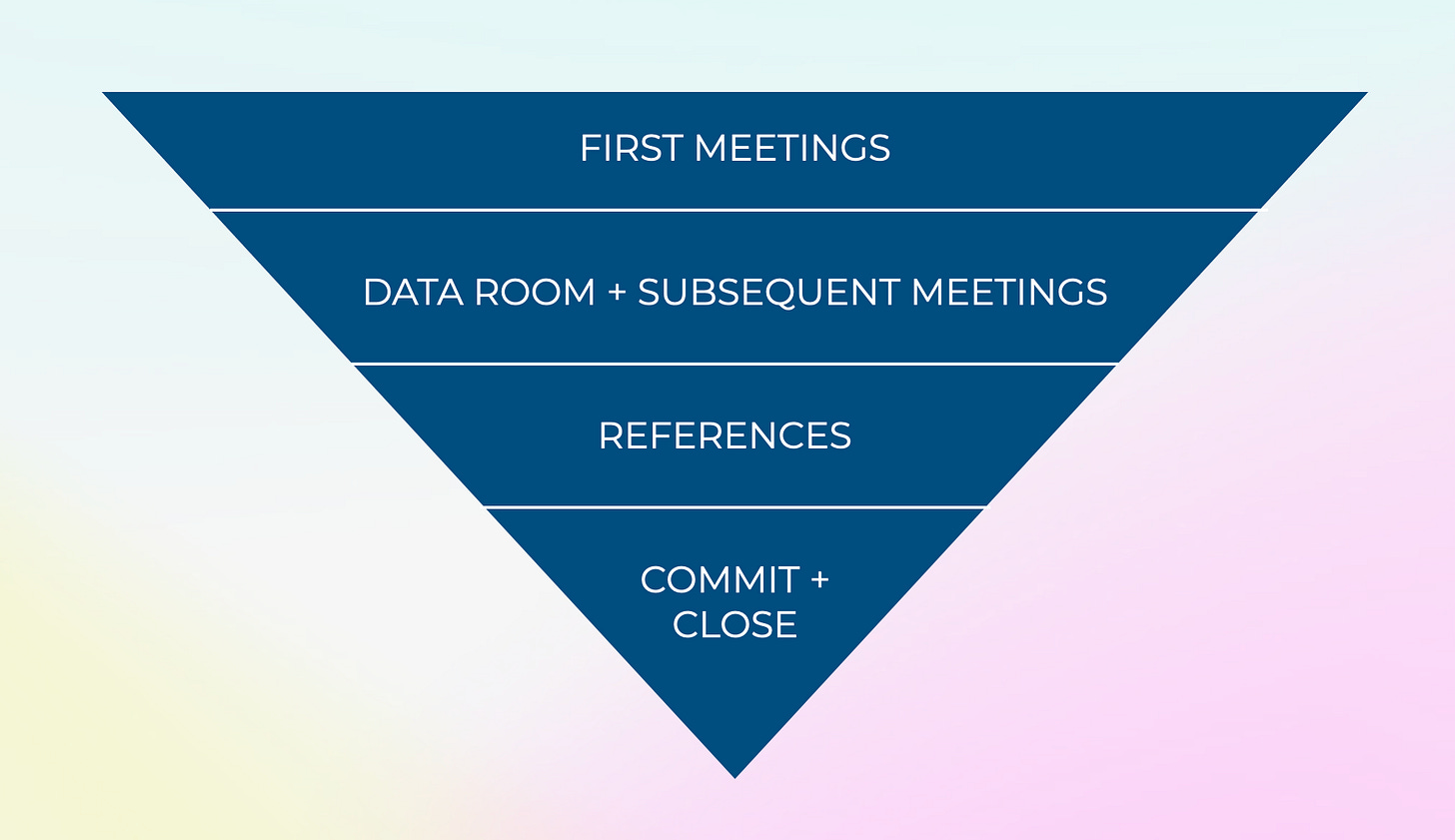

One of the best pieces of advice I got on the fundraise process came from Ophelia at Blossom Capital, also ex-Index, who said to treat fundraising like a sales process. You have to think in terms of conversion funnels: how do you move people down funnel while continuously refilling top-of-funnel?

For first meetings, I found that most LPs want to hear the pitch and start building the relationship, even if it’s just to put you in their CRM. Many of these meetings aren’t near-term actionable—an LP might not invest in you until Fund III or IV, and you might be too small for them today—but you’re doing yourself a favor for when you raise future funds. (This can get frustrating, of course, when the current version of you just really, really wants to get Fund I done.)

I also found conversion from references to close—the final step above—to be strong, meaning that I just needed to get people to the reference stage. Easier said than done. The most difficult conversion for me—and I suspect for many managers—is moving from first meeting to really digging in with an LP. This is the conversion from “curious” to “serious.” There’s little incentive for an LP to come into a first close (a venture fund might have three or four closes); why commit early when you can see how the portfolio develops, see who else comes in, and see where the market is at when final close rolls around? This means that it’s difficult to create urgency: there’s no urgency without scarcity.

The best path around this, in my mind: close some capital from early believers and start deploying. When you show that your strategy isn’t just something on a page—you’re able to source, win, and support great companies—the raise gets a bit easier.

Another thing I realized—eventually—is that you have to find LPs who are buying the product you’re selling. If someone hasn’t backed a Fund I in years, they’re probably not going to back yours. If an LP’s recent commits are to the a16zs or General Catalysts of the world, it’s not likely their next will be to a first-time fund. Those LPs are buying a different product: a reliable ~10% IRR vs. the opportunity (yes, albeit less certain) for 30%+ IRRs.

The LPs who are a fit for emerging managers are those who understand the math: emerging managers outperform, largely due to fund size.

If you’re trying to convince an LP that emerging managers are a compelling category, you’re already fighting an uphill battle.

There are a dozen reasons not to invest in a ~30-year-old’s ~$30M fund. But there are also a few good reasons to invest (I’m biased!), namely the opportunity to generate outsized returns. A $3M check can feasibly turn into $30M or more in a small fund; investing in the large multi-stage firms, you’re probably looking at a 2-3x multiple. More on the artisan vs. asset manager bifurcation in a moment.

In whole, the fundraise process gave me a lot of empathy for the founder journey. It’s made me better at running a good process, communicating well, and always closing the loop after meeting a founder. That’s where relationships and reputations are built.

The Strategy: Thesis-Informed, Founder-Centric

We focus on technology’s application layer: internet, software, and AI applications with the potential for viral adoption and typically with a network effect. Every company we partner with should be a potential generational company and a potential fund returner. More on the portfolio construction math in a bit.

On our thesis: last month I wrote a longer piece, Techno-Optimism and Horizon Expansion, that digs into Daybreak Thesis 1.0.

That piece goes into more depth, but the thesis is built around six pillars, shown below. We’ve now backed companies in each pillar.

Examples in each, to help bring the thesis to life:

Health: As more women wait longer to have children (the average age of a first-time mother is now 28 in the US, up from 25 two decades ago), Elsa is building tools for clinics to manage the fertility journey end to end. If you’re considering egg freezing or IVF, check out Elsa here for a fertility assessment.

Sustainability: Barnwell just came out of Stealth. Barnwell is a platform for animal health intelligence, helping farmers monitor and mitigate the spread of disease—very timely with bird flu. More about them in TIME here.

Learning: We have a Stealth company that’s an AI companion for learning. You can generate a multi-media course on any topic you can imagine. AI is the clear “why now” that learning has been waiting for (see: July’s How AI Will Change Education).

Money: We have a Stealth company building AI for wealth advisors, helping advisors be more efficient and take on more clients. The company also makes it economical for advisors to take on clients with lower net worths, expanding the wealth advisor market.

Community: Sound Games is building the future of game publishing with AI. The company rides the shift to indie games and to cross-platform gaming.

Job Creation: LaborUp just came out of Stealth last week. The company is built for skilled manufacturing workers—think: machinists at Ford or welders at Boeing—helping them find jobs and helping employers manage the recruiting process.

My view has always been that for early-stage venture, you can be thesis-informed, but have to be founder-centric.

You get into trouble when you fall too in love with your own theses. The best founders will always be three levels deeper and three steps ahead. Having a good thesis means having a prepared mind for where the world is going and for which startup opportunities exist—that’s the point of Digital Native—but at the end of the day, it’s all about identifying exceptional people and winning the right to work with them.

I liked that the Fortune piece focused more on principles of good product design and human behavior—things that don’t change, and that are applicable across consumer and enterprise.

The Philosophy: Artisans, Not Asset Managers

I’ve written in the past about how venture capital is ballooning into asset management. This visual from PitchBook captures it well: nine VC firms collected 50% of all money raised in 2024; 30 firms collected 75% of all money raised.

Venture is splitting into asset managers vs. artisans.

I once heard Floodgate’s Mike Maples frame it well while on stage with a multi-stage firm: “We’re in the same industry,” he said, “but we’re no longer in the same business.” That succinctly captures the shift: the Floodgates and Daybreaks of the world are in a different business than the a16zs and GCs.

Here’s another way to look at this shift: check out how the average capital raised by the U.S. VC firms is going up, while the median stays the same or declines slightly. This means the big firms are guzzling up more and more capital, pulling up the average.

Later-stage venture is more about capital allocation; founders want to price optimize. Early-stage venture is more about company building; founders want to optimize for the most helpful, well-connected, values-aligned partner.

Of course, incentives are typically skewed in venture. It’s hard to resist the fees game. Consider this stat: the net present value of management fees alone for a fund at $1,000M exceeds the fees and carry of a fund at $200M, even if the latter returned 4x (!). No wonder firms become PE-ified and grow larger and larger.

We’re even seeing firms like General Catalyst consider an IPO—here’s a headline from last week:

This means following in the footsteps of PE giants like Blackstone, KKR, Apollo, and TPG. Private equity firms, by the way, are largely valued in the public markets on the basis of cash flows from fees. This further skews incentives for multi-stage VC firms with asset manager ambitions.

At the end of the day, venture capital is a services business. I like how Blake Robbins puts it: “The irony is that most VCs would never invest in a service business—they’d tell you it doesn't scale. Yet somehow we’ve convinced ourselves that venture capital should scale.”

Services don’t scale. The goal for Daybreak is to remain artisanal and craftsman-like, rather than resisting the urge to accumulate assets and fees. A common saying in venture is, “Your fund size is your strategy.” The implied meaning here is typically around portfolio construction, which we cover next. But your fund size is also your strategy when it comes to values alignment and level of involvement.

The Math: Daybreak Portfolio Construction

One rule of thumb for venture capital: trust the math.

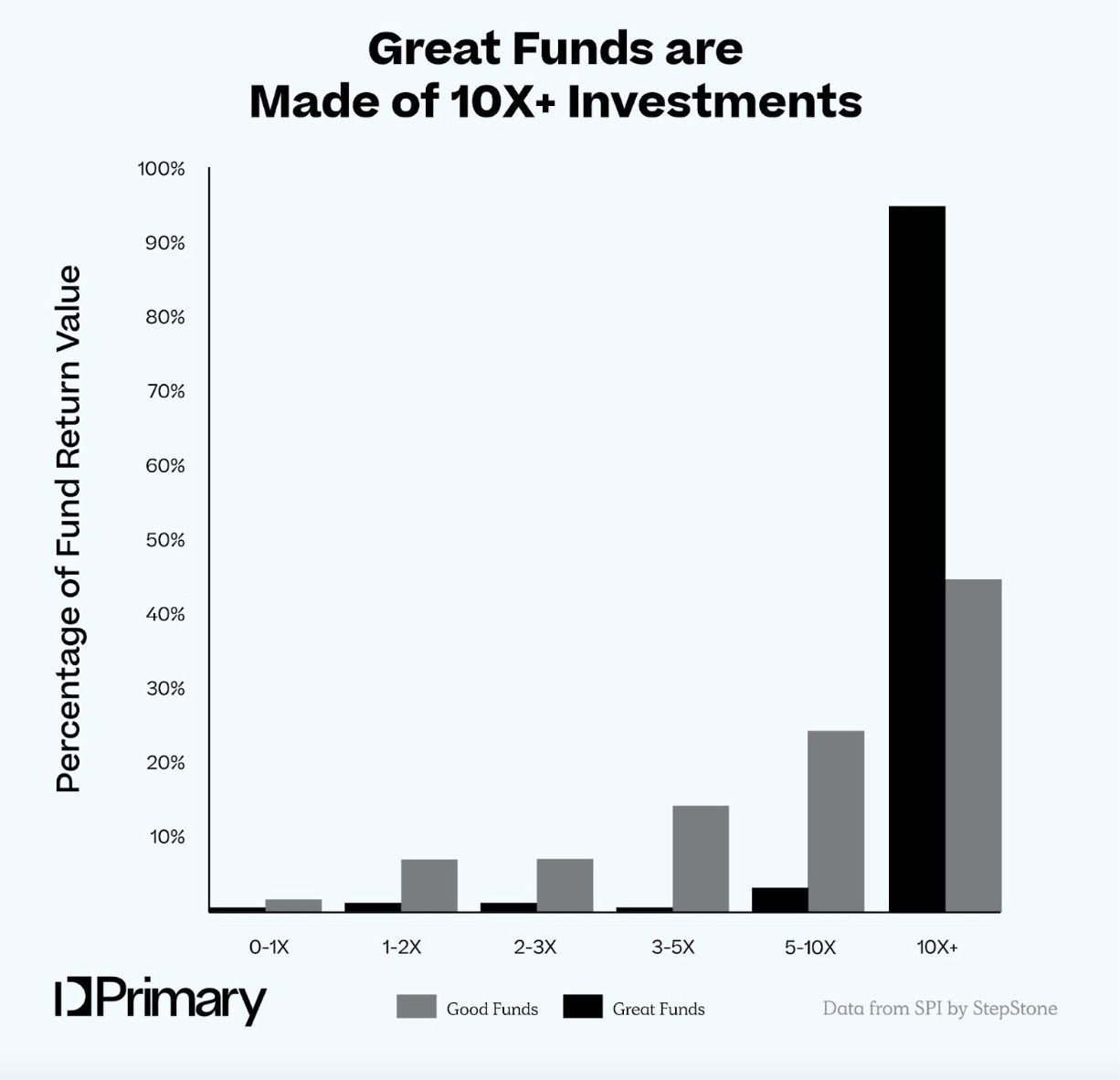

Fund size = strategy because fund size dictates check size and ownership, determining what level of outcomes you need to generate great returns. There’s a lot of data that smaller venture firms outperform. To re-share the chart from earlier:

Or consider a recent study from PitchBook and Sante Ventures, which found that venture funds smaller than $350M are 50% more likely to generate a 2.5x return than funds larger than $750M. A saying goes: there are a dozen ways to 10x a $30M fund; there’s only one way to 10x a $3B fund. That’s oversimplified, but let’s run through some math.

When launching Daybreak, we honed in on $30M as the magic number for fund size. We’re trying to balance two things:

We need enough companies to allow for the power law of venture to work,

But we need to write large enough checks to get sufficient ownership, so that when the power law does work, it matters.

Venture is a power law industry: most of the returns are concentrated in a few companies. StepStone and Primary did an analysis of “good” and “great” funds, finding that in great funds, ~95% of returns come from 10x+ investments.

This is an industry of home runs, not second-base hits. A small handful of companies will drive returns. As a result, every company we partner with at Daybreak should have the potential to be a $1B+ business (ideally $5B+) and to return the entire fund.

Here’s one way to think about fund math. Take a $33M fund like Daybreak Fund I. If we want to 5x the fund (hopefully we can do better), we’ll need to generate $33M x 5 = $165M. If our average ownership at exit, with full dilution, is 5%, our companies need to be collectively worth $165M / 5% = $3.3B.

We can achieve this in different ways. Maybe we have three unicorns. Maybe we have one company worth $3B and the rest zeroes. Maybe we have 10 companies acquired for $300M each. You get the picture. This is the meaning behind the quote above about a dozen ways to get a good multiple on a smaller fund. If you’re looking to get top-decile returns on a multi-billion-dollar fund, your options get a lot fewer.

Studying the portfolio construction of top-performing Seed funds, it becomes pretty simple:

About 5% of your companies need to be 100x outcomes.

Another 10-15% need to be 20x outcomes.

Mike Maples has a good podcast on 20VC about Seed portfolio construction. I like how he frames his misses: “failures of imagination.” He cites the example of Airbnb, failing to see how big it could get. In a power law industry, it’s failures of imagination that hurt—you can only lose 1x your money, but you can earn 1,000x+ upside. Here’s a very oversimplified, much-footnoted chart that captures what being in Seed round of generational companies might entail:

For Daybreak, we write $500K-1M checks, largely at Pre-Seed. We aim to be a founder’s first check, and we look for good ownership—ownership that warrants the time we’ll devote to a company. It’s tough to return a fund on a toehold ownership position: the “what you have to believe” just doesn’t make sense. For new funds, it can be difficult to resist hot funding rounds—especially rounds led by top firms—but if the ownership doesn’t make sense, the math doesn’t work.

In the past, we’ve shared example portfolios to drive home the math we’re talking about here. To re-share those examples—

Say we make 30 investments of $1M each for 10% initial ownership. Here’s what the distribution of outcomes might look like for Companies 1 through 30. Six companies return capital; the rest are zeroes.

This speaks to the power law, and you can see why ownership is important. This model assumes we take 50% dilution by exit, so our 10% becomes 5% ownership. If we entered with only 5% ownership, the 6.0x fund becomes a 3.0x fund. If we can manage 15% initial ownership instead of 10%, we rise to 8.9x. (All these returns are gross, by the way, not net.)

Of course, the math above is hugely oversimplified. This basic model doesn’t take into account reserves for follow-on investments, for one, or about a dozen other variables. But it makes the point: when it comes down to it, this job is about (1) good ownership in (2) great companies. That’s about it.

The loss ratio modeled above is conservative; good venture firms typically have much lower loss ratios (around 50%). But returns are almost always clustered around a few home-runs.

What if a Seed fund like Daybreak can be in the next Figma, Snap, Roblox, or Unity? That’s the goal. In that case, even if we have 29 companies return zero (a 97% loss ratio), the one winner powers a 14.3x fund. This is the beauty of a small fund.

Good luck getting a 14x on a large firm’s fund.

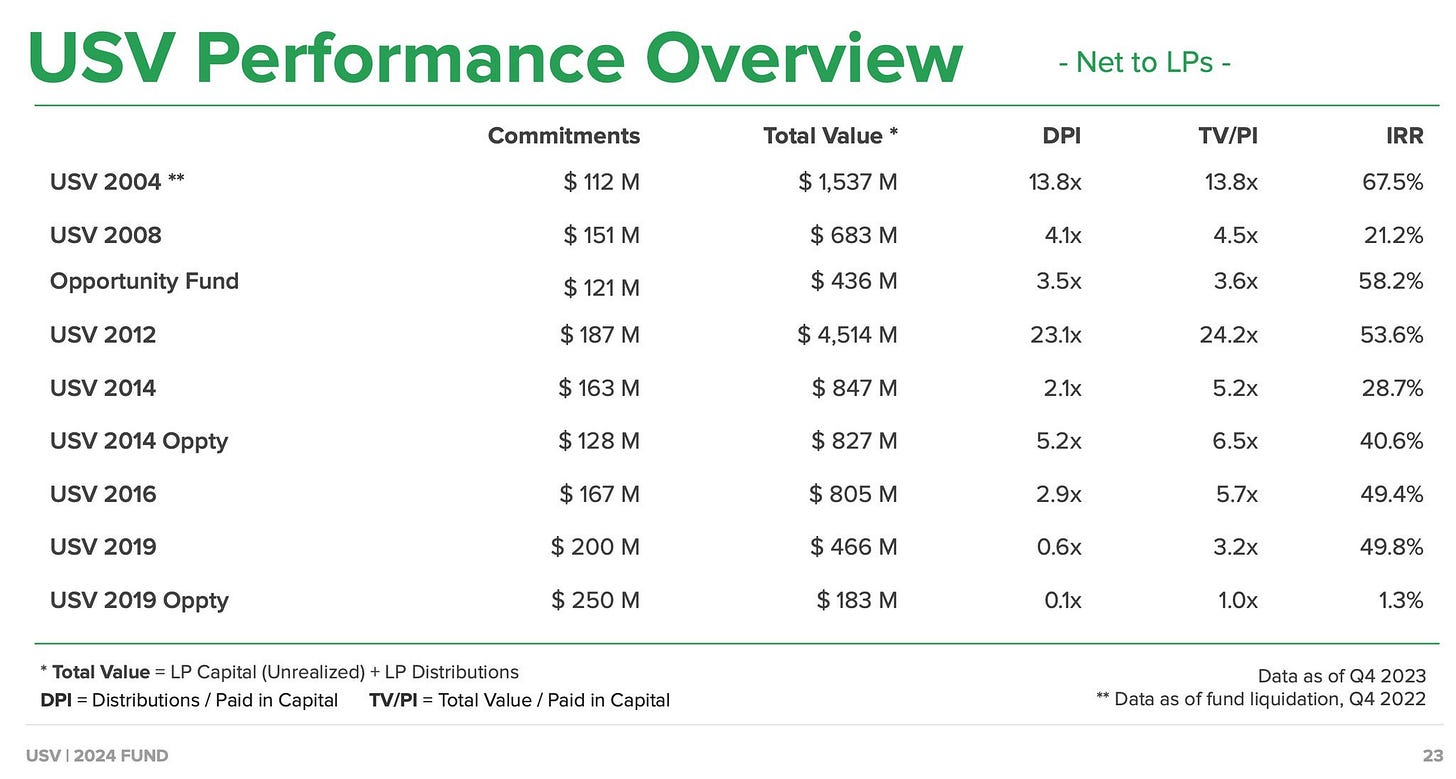

USV’s fund performances recently trended on Twitter. In many ways, USV pioneered the artisanal, thesis-driven investing that Daybreak is built on. You can see the results of their fund size discipline:

A $187M fund creating $4.5B of value? A cool 23x net return? Not bad.

What USV illustrates so beautifully is that venture should be a performance game, not a fees game. And the example portfolios above are good reminders—particularly in frothy times like our current AI moment—that at the end of the day, you have to trust the math.

The Vision: Where Daybreak Goes From Here

So where are we going from here?

There’s a lot of the “we” pronoun in this piece, but Daybreak remains a one-man band. I say “we” because, well, “I” feels a bit ego-centric—and because Daybreak has always been envisioned to be more than one person.

We’ll never be an army of investors, but we’ll grow the team. In the not-so-distant future, we plan to add a second investment partner. We may also add a Head of Talent to help our companies recruit early engineers, designers, and sales people. I’m thinking through what other roles will move the needle.

This is the cover page of the original fundraising deck for Daybreak Fund I, which I made in Midjourney when we got started:

It’s pretty, but a little lonesome. I imagine future fundraising decks will evolve the cover art, eventually looking something more like this creation I just spun up:

As our team grows, our fund sizes will grow, as will our average check size and our ability to lead and co-lead larger rounds. But we’ll always stay disciplined, lean, and more artisan than asset manager.

One thing that won’t change: we’ll continue to build in public. I’ll aim to share updates, roughly quarterly. These will hopefully be helpful to others—both founders and fund managers—and also helpful to us, acting as a forcing function for our own clarity of thought. My hope is that in 10 years, we can look back at this piece formally announcing Daybreak Fund I—and a decade’s worth of writing on the firm-building, fundraising, and investing processes.

As always, open to any and all feedback, wisdom, or advice! A huge thank you to our Daybreak founders, LPs, and collaborators—as well as to this Digital Native community, which has been a tremendous source of wisdom for stress-testing ideas and for connecting with smart people. It’s taken a village to get to this point, and I’m sure it’s going to taken even more to continue executing on this vision.

See you next week, when we’ll be back to our regularly-scheduled Digital Native programming!

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: