Seurat and the Opportunity in Vertical AI

Why AI Lends Itself Naturally to Verticalization

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 55,000+ weekly readers by subscribing here:

Seurat and the Opportunity in Vertical AI

One of the common mistakes in startups and venture capital: underestimating market size.

I made this point in last fall’s The Art of Early-Stage Investing, using examples that ranged from Taylor Swift to Uber. The takeaway: great products and great founders expand markets.

To revisit Swift: she’s indisputably music’s dominant superstar; last year she single-handedly accounted for 1.8% of all music consumption in the US, making up one of every 78 songs streamed and five of the year’s 10 biggest albums. Over the weekend, Swift added a historic fourth Album of the Year Grammy to her mantle, breaking her three-way tie with Stevie Wonder, Frank Sinatra, and Paul Simon (three wins each). Swift is the envy of every record label.

Back in the mid-2000s, RCA Records had the chance to sign a young Taylor Swift, but RCA didn’t see a sizable market for a teenage country singer. After all, country music was on the decline with young listeners. So the execs at RCA made a critical mistake: they underestimated Swift and her market. It turned out, of course, that Swift would vastly expand the country market before further expanding her empire as a cross-genre superstar. Again, great products and founders expand markets.

The same truism extends to startups. Total Addressable Market (TAM) analyses often lead a founder or investor astray. A classic example is Uber. As Bill Gurley outlines in a great post from 2014, many people dramatically underestimated Uber’s market opportunity. One finance professor at NYU, Aswath Damodaran, wrote in Uber’s early days: “For my base case valuation, I’m going to assume that the primary market Uber is targeting is the global taxi and car-service market.” He arrived at a TAM of $100B.

Damodaran’s error, of course, was failing to recognize that Uber’s product would expand the market. Uber offered a 10x better offering than taxis:

✅ Coverage density was higher, which drove down average wait times to under five minutes

✅ Geolocation on mobile devices enabled anyone to call a car, nearly from anywhere

✅ Payment was done via mobile, meaning customers didn’t need to carry cash

✅ The dual rating system ensured quality

✅ Digital record of each ride meant that Ubers were safer than cabs

In New York, the taxi capital of America, ride-hailing apps quickly overtook traditional cabs, revealing that a 10x better product could crowd in more riders.

As Gurley puts it: “The past can be a poor guide for the future if the future offering is materially different than the past.” It’s sort of like sizing the Mixed Reality market as if the Vision Pro didn’t come out; that product will vastly expand the market. I like this tweet from Box’s Aaron Levie:

Gurley points to a similar mistake made by McKinsey, forty years ago:

“In 1980, McKinsey & Company was commissioned by AT&T (whose Bell Labs had invented cellular telephony) to forecast cell phone penetration in the U.S. by 2000. The consultant’s prediction, 900,000 subscribers, was less than 1% of the actual figure, 109 million. Based on this legendary mistake, AT&T decided there was not much future to these toys. A decade later, to rejoin the cellular market, AT&T had to acquire McCaw Cellular for $12.6 billion. By 2011, the number of subscribers worldwide had surpassed 5 billion and cellular communication had become an unprecedented technological revolution.”

Oops.

Many startups have defied their markets. Airbnb popularized home-sharing. Tesla brought electric vehicles mainstream. Red Bull effectively created the energy drink market, which now comprises $53B globally and is expected to grow 7.2% a year through 2027. (For its troubles, Red Bull owns 43% of the market.)

Those examples are consumer businesses, the types of businesses we often think of when we think of market size fallacies. But market sizing can also be an error in enterprise software.

Vertical Software

For many years, venture capitalists thought vertical software was too “niche” to drive venture-scale outcomes. Horizontal software was more attractive. People can use Microsoft, Salesforce, and ServiceNow whether they work at a law firm, a bank, or a tech company. Those companies are rewarded for their versatility with $100B+ market caps.

Yet the last decade has shown that markets once thought of as niche can be larger than anticipated. Toast built vertical SaaS for restaurants. Procore built vertical SaaS for construction. Veeva built vertical SaaS for life sciences. Toast and Procore both trade at $10B market caps, while Veeva trades at a whopping $33B.

We’re now seeing vertical AI as a related, though slightly distinct trend. My view is that when it comes to vertical AI, direct industry expertise will often trump technical prowess.

To start a technology company, you used to need a strong technology background. Now, with the rise of no-code, low-code “building blocks” that remove complexity—think AWS and Stripe, for instance—more people are able to build tech products. Technology itself is rarely the differentiator (outside of deep tech and infrastructure); more often, it’s a unique product insight. This bodes well for vertical SaaS and AI, where specific industry knowledge and insights matter.

I expect we’ll see many entrepreneurs emerge with non-traditional backgrounds. The former lawyer might be better at building the legal AI application than the non-lawyer engineer, the former construction manager might have unique insights on how AI can be applied to his industry, and so on.

The Playbook: Killer Feature + Expansion

When I think of vertical SaaS, I think of a Seurat painting. Bear with me.

Seurat is famous for creating the painting technique known as pointillism. He’s probably most famous for his 1884 work A Sunday on La Grande Jatte—if you’ve seen Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, you’ll remember the painting (it’s still on display in the Art Institute of Chicago today).

Up close, a Seurat painting doesn’t resemble much; it’s just a series of dots. At first glance, vertical SaaS and AI don’t look like much.

Toast’s first product was a cloud-based point-of-sale system for restaurants. It seemed niche. But over time, Toast layered in over a dozen products: inventory management, lending, payroll, marketing, digital ordering, delivery. According to Barron’s, 62% of Toast customers use 4 or more of its 15+ products.

All of a sudden, zooming out, the company is a one-stop-shop for everything a restaurant needs to operate. It no longer seems niche. Same for a Seurat: zooming out reveals a rich, expansive work.

The playbook for vertical SaaS looks something like:

Identify the most salient pain-point for your customer and solve it.

Use that wedge to win over customers.

Layer in more products over time—cross-sell and up-sell, improving customer lifetime value and becoming more defensible.

A vertical SaaS company might start out looking like a feature—a single dot of paint—but over time it becomes a constellation of products with a strong moat.

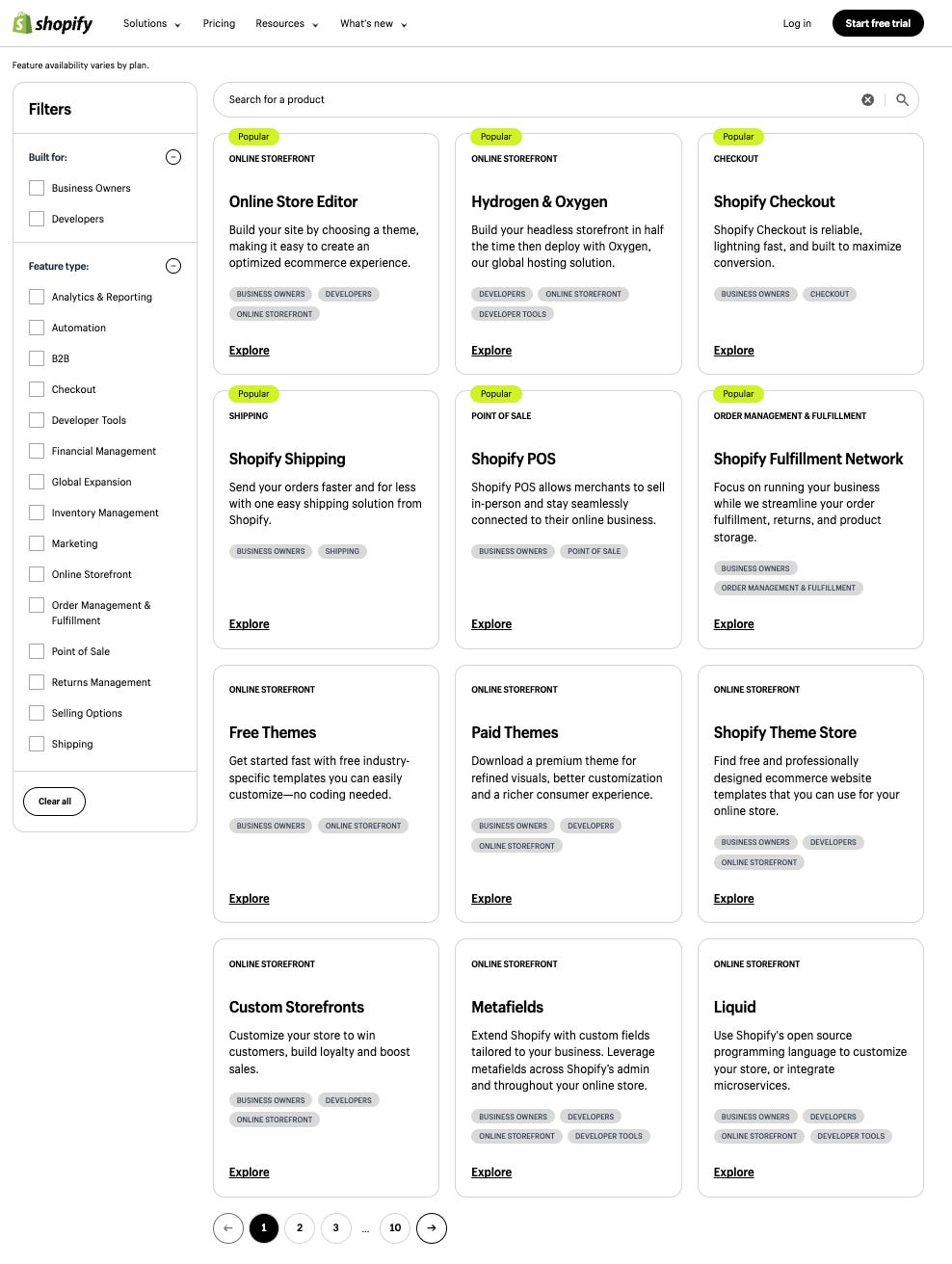

Shopify started by letting a merchant build a website with a shopping cart integration. Now, Shopify’s list of products on its website runs 10 pages long (!). The company has also become a platform with its own robust third-party app ecosystem.

Building out a broad suite of products allows for cross-sell and up-sell. Some products might ultimately become even larger than the initial “hero product.” Shopify, for instance, makes more today from payments (which it calls “Merchant Solutions” in its filings) than from its subscription service: $1.7B vs. $1.3B in the most recent quarter.

Vertical SaaS Has Room to Run

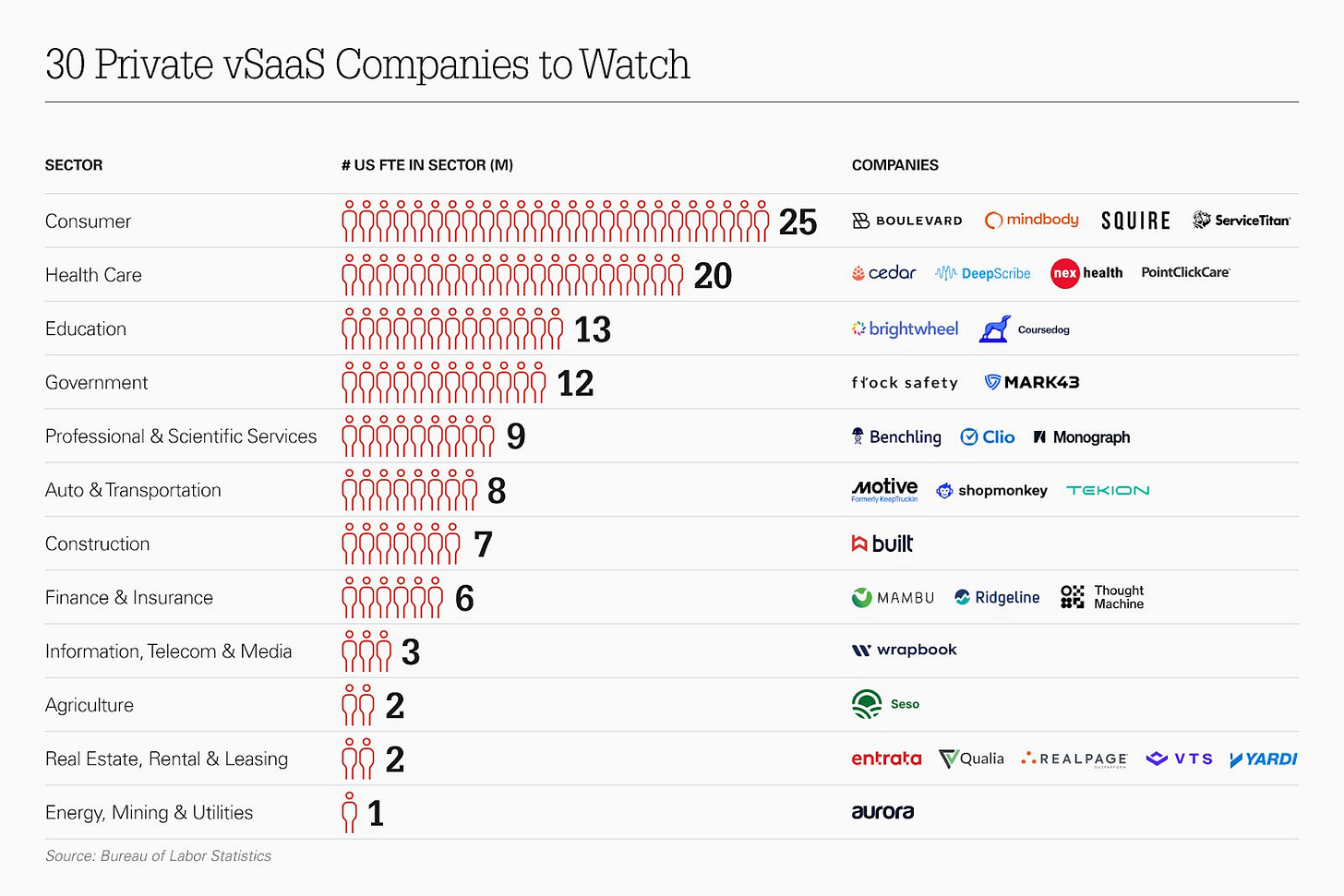

Software dominated the 2010s; hundreds of well-funded startups have tackled vertical SaaS. Nearly every category has multiple players. Here’s a good visual from my former colleagues at Index:

It might seem like vertical SaaS is saturated. But there are still (many) opportunities lying in wait. I recently talked to some family members about their lines of work. One aunt is a nurse. A cousin’s husband works in farming. Another aunt is a director of youth sports. All of them explained the pen-and-paper workflows they use to run their day-to-days; none of them use software.

Youth sports might sound small, but it’s a $38B market in the United States. Is the best solution really for coaches to send kids home with paper sign-up forms and waivers for their parents to sign? Who facilitates discovery? How are payments handled?

In 2022, I wrote The $100 Trillion Opportunity in Marketplaces about B2B marketplaces. An estimated $100 trillion flows between businesses each year, a 4-5x multiple of transaction volume between businesses and consumers. Yet only about 5-10% of B2B transactions happen online and—in the year 2024!—about 50% of transactions are still done over the phone, over fax, or via in-person meetings with sales reps. The entire B2B ecosystem is inefficient, opaque, and convoluted.

Many of the best B2B marketplaces are tacked on to vertical SaaS solutions. Vetcove, for instance, has quietly built a formidable business allowing vet hospitals to order supplies. Faire, the central example in that 2022 piece, is in many ways also vertical SaaS for independent retailers and brands.

In order for vertical SaaS companies to become defensible, they should become more than features; ideally, they build in a network component. To continue with the veterinary space, an excerpt from last fall’s piece on early-stage investing:

Say you build software for veterinarians. Maybe you build a scheduling system that lets vets book their customers. You charge $10 a month. Over time, a dozen other vet booking systems emerge and competition erodes prices down to $5. Switching costs are low, you have no leverage, and your margins wither away.

Now say that you instead build the scheduling software, but you quickly integrate payments—all the dollars are flowing through your software. You add a network component where vets can chat with other vets, where customers can chat with other customers, and where people can even upload profiles for their pets with health records across various vet clinics. All of a sudden, your tendrils have worked their way into every facet of the veterinary ecosystem; good luck ripping out your software now.

This playbook is far from run dry. It can still be applied across dozens of industries that remain frustratingly analog.

Vertical AI vs. Vertical SaaS

In AI applications, defensibility comes in the form of better data, which is used to train better models. Those better models lead to better products. Better data goes hand-in-hand with focus and specificity, making AI unique suited to verticalization.

The wave of vertical AI will see both incumbents—namely, vertical SaaS players—and AI-native upstarts. Incumbents have moved quickly. Shopify, for instance, has expanded that long list of products above with AI products. Shopify Magic offers AI-generated product descriptions for e-commerce sites.

Many vertical SaaS incumbents are sitting on troves of highly-valuable, highly-specific customer and industry data. This gives them an edge for building AI products.

But there are also openings for AI-native players to further reinvent vertical workflows. Many such players have arrived over the last couple years. To give just a few examples:

Harvey helps lawyers with contract analysis and due diligence.

SketchPro helps architects with their design renderings.

Causaly helps biomedical researchers search clinical trial databases to answer research questions.

Cradle helps people in biotech with better protein sequencing.

Ambience started with an AI medical scribe for doctors and has since expanded into a broad range of healthcare-focused products (yesterday, it announced its Series B).

The old-world per-seat SaaS pricing may no longer make sense here—if Harvey reduces the number of seats you need (fewer paralegals?) should it really be priced on a per-seat basis? Or should it be priced on the amount of work done or time saved?

We’re still in the early innings for vertical AI applications. The companies that win will follow the same vertical SaaS playbook: start by solving a salient pain-point (informed by a unique industry insight), then expand the product suite to drive up LTV and build a moat.

Final Thoughts

We’ve become spoiled by the technology products we use; polished, intuitive, elegant tech products are now table-stakes, in both consumer and enterprise. Naturally, this should expand to every industry. There’s no reason the construction worker or farmer or vet should be ordering supplies or managing inventory with pen and paper.

Open-source models mean that AI applications can be built and fine-tuned on proprietary datasets; the differentiation comes at the application layer, not in the underlying technology. Differentiation comes from unique product insights, which come from working in the industry or talking to many, many customers.

The playbook is familiar, and we’ll see vertical AI become the new vertical SaaS. Dozens of industries remain relatively untouched by technology. That’s about to change.

Sources & Additional Reading

My former colleagues Nina and Paris have some good reads on vertical AI and vertical SaaS; they’ve both been instrumental in informing my thinking on the space

Cowboy had a good market map and deep-dive into the emerging vertical AI landscape

Related Digital Native Pieces

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: