The Art of Early-Stage Investing

Rules of Thumb for Evaluating Market, Product, & Founder

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. If you haven’t subscribed, join 50,000+ weekly readers by subscribing here:

The Art of Early-Stage Investing

Venture is a power law business.

Last week’s math exercise made that point: it’s often 1, 2, 3 companies driving a fund’s returns. Top Seed funds often have a 40% loss ratio, meaning that 40% of investments are zeroes. The middle third of companies might comprise ~20% of returns, and the top 20-30% (often just a handful of companies) will drive the remaining ~80% of returns.

That portfolio construction model was oversimplified, assuming that only 3 of 25 companies return any capital. But it got the point across: having outlier companies—and maintaining good ownership in them—is crucial.

Last week’s Seed Investing: The State of the Union dug into the current and future market dynamics for early-stage venture. We also launched the Daybreak website and shared that we’re allocating a portion of Daybreak Fund I to members of the Digital Native community. Most of the Limited Partner base will be traditional venture LPs, but it’s important to me to keep a portion for people who have been part of this community. It’s a small step toward democratizing venture.

Thank you to everyone who filled out the form last week—I’ll aim to get back to folks next week after the holiday. If you’re interested in being an LP in Daybreak, you can fill out the form here:

The power law nature of venture means that picking the right companies is everything. Picking is the focus this week.

A single company can shift a fund from 2x to 10x+. My view—which underpins how we invest at Daybreak—is that every Seed investment should be a potential fund-returner. This isn’t a business of first- and second-base hits; it’s a business of homeruns. Early-stage investors and venture-backed founders should swing for the fences. Venture isn’t a product for everyone—in fact, it’s not the right product for most companies; more on that later. But it’s the right product for companies with the potential to be compounding, enduring, market-transforming businesses.

Many Digital Native pieces focus on the big macro shifts—in technology and in human behavior—and on the startups that ride and accelerate those shifts. I don’t think I’ve written about the actual nuts and bolts of investing before. So this piece is a little different: the goal is to dig into what to look for when evaluating whether a company can become a $5B+ business.

I’ll build the piece around Market, Product, and Founder:

MARKET: What Can Go Right

PRODUCT: Platforms & Networks

FOUNDER: Clarity of Thought & X-Factor

Let’s dive in👇

Market: What Can Go Right?

Market Sizing

One hot take I have: market size doesn’t really matter.

I wrote about this back in March—in, of all pieces, a piece called What Taylor Swift Can Teach Us About Business. How does Swift relate to market sizing? RCA Records had the chance to sign a young Taylor Swift, but they didn’t think there was a sizable market for a teenage country singer. After all, country music was on the decline with young listeners. So RCA made a critical mistake: they underestimated Swift and her market. It turns out, of course, that Swift vastly expanded the country market before further expanding her empire to encompass mainstream pop (e.g., 1989), indie-folk (e.g., Folklore & Evermore), and even some questionable dubstep (I Knew You Were Trouble) and rap (End Game, not my favorite).

The lesson: great products and great founders expand markets.

The same truism extends to startups.

I try to not get too caught up on Total Addressable Market (TAM) analyses, unless a founder is going after a really niche market or doesn’t have a good sense for how their product will expand the market.

Startup history is littered with market sizing mistakes that caused early investors to miss the train.

A classic example is Uber. As Bill Gurley outlines in a great post from 2014, many experts dramatically underestimated Uber’s market opportunity. One finance professor at NYU, Aswath Damodaran, wrote in Uber’s early days: “For my base case valuation, I’m going to assume that the primary market Uber is targeting is the global taxi and car-service market.” He arrived at a TAM of $100 billion.

Damodaran’s error, of course, was not recognizing that Uber’s product could expand the market. Uber offered a 10x better offering than taxis:

✅ Coverage density was higher, which drove down average wait times to under five minutes

✅ Geolocation on mobile devices enabled anyone to call a car, nearly from anywhere

✅ Payment was done via mobile, meaning customers didn’t need to carry cash

✅ The dual rating system ensured quality

✅ Digital record of each ride meant that Ubers were safer than cabs

In New York, the taxi capital of America, ride-hailing apps quickly overtook traditional cabs, revealing that a 10x better product could crowd in more riders.

As Gurley puts it: “The past can be a poor guide for the future if the future offering is materially different than the past.” I always liked this tweet from Box’s Aaron Levie:

Gurley also points to a similar mistake made by McKinsey, forty years ago:

“In 1980, McKinsey & Company was commissioned by AT&T (whose Bell Labs had invented cellular telephony) to forecast cell phone penetration in the U.S. by 2000. The consultant’s prediction, 900,000 subscribers, was less than 1% of the actual figure, 109 million. Based on this legendary mistake, AT&T decided there was not much future to these toys. A decade later, to rejoin the cellular market, AT&T had to acquire McCaw Cellular for $12.6 billion. By 2011, the number of subscribers worldwide had surpassed 5 billion and cellular communication had become an unprecedented technological revolution.”

Oops.

Great products expand markets. I often ask founders the question: what do you think has to go right for this to be a massive business?

Many startups have defied their markets. Airbnb popularized home-sharing. Tesla brought electric vehicles mainstream. Red Bull effectively created the energy drink market, which now comprises $53B globally and is expected to grow 7.2% a year through 2027. (For its troubles, Red Bull owns 43% of the market.)

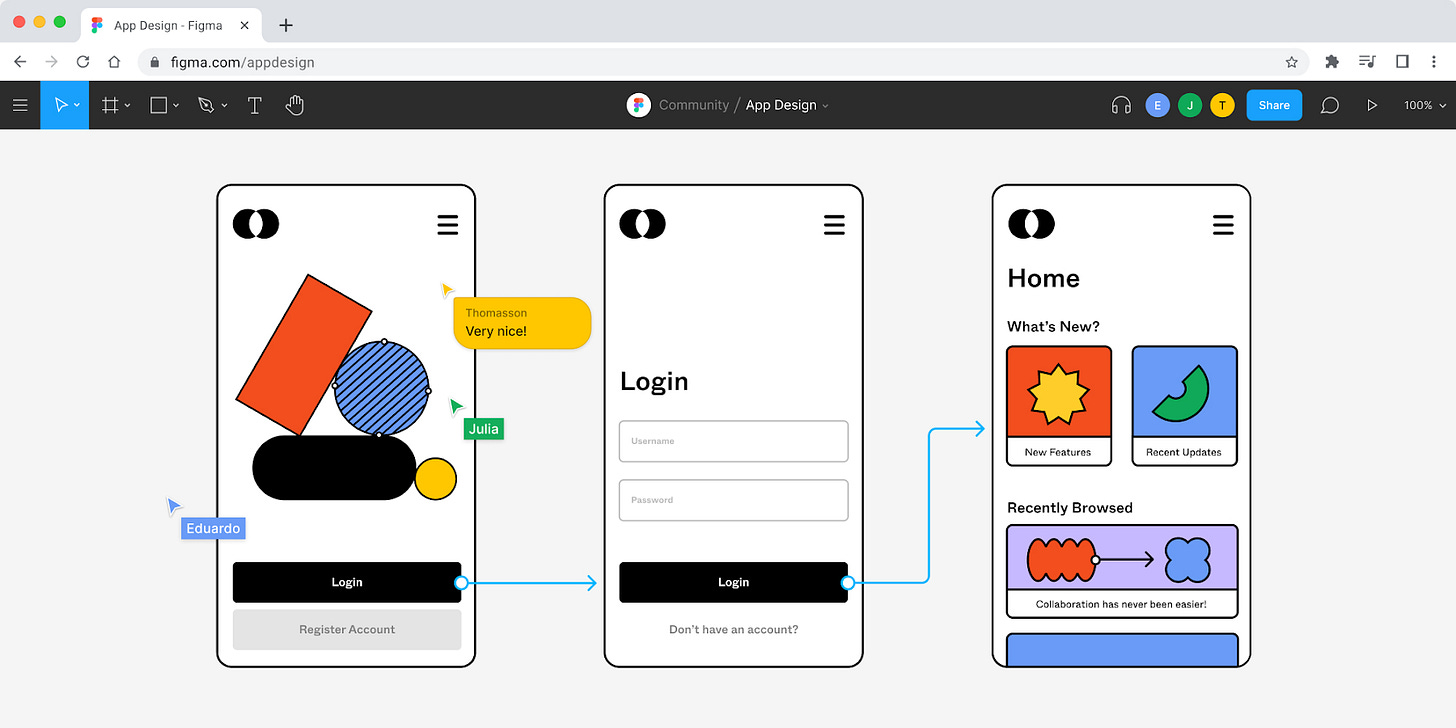

The list goes on. Many investors I know regret passing on Benchling, which makes software for life sciences, because they thought life sciences was too small an opportunity; Benchling proved them wrong. One investor I know passed on Snap because how could the market for disappearing photos be very large? (The answer is that a product visionary like Evan Spiegel could create a large market.) Others passed on Figma because their TAM analysis focused on the number of designers; they missed the key insight that Figma’s real-time collaboration made design a cross-functional discipline, with engineers and product leaders and management also becoming paid users.

Figma offers a nice segue into market timing.

Market Timing

Market sizing I don’t believe in; market timing I very much do. In fact, outside of the entrepreneur, timing might be the single greatest determining factor for a startup’s success.

Figma is a good jumping-off point. Figma benefited from an exceptional team; Dylan and Evan are extraordinary. But Figma also rode the wave of WebGL, which renders high-fidelity, interactive 2D and 3D graphics in the browser.

Its timing was perfect. WebGL came out in 2011; Figma was born in 2012. As co-founder and CEO Dylan Fields puts it:

It was like, “Okay, WebGL lets you use the GPU, your computer, and the browser. What can we do with that?” So we started proving it out. [Evan] had made a bunch of tech demos already, and we started to look at it in the context of professional-grade tools and eventually interface design.

The more we built with WebGL, the more confident we were that this could be a technology we could use to go build a professional-grade interface design tool. But no one believed us. I kept trying to recruit people, and I found that if I didn’t show up and immediately open my laptop to show them the tool working, they just wouldn’t believe me.

In the early 2010s, Sketch and InVision were the would-be Adobe disruptors. Figma leapfrogged them both.

When it comes to market timing, there are many stories of companies that were too early. In the early 2000s, venture capitalists—including Sequoia and Benchmark—invested a total of $396M in Webvan, an online grocery delivery business. At its peak in 2000, Webvan brought in $179M in sales. But it had $525M in expenses that same year, and three years into its operations it declared bankruptcy. (Fun fact: Webvan was founded by Louis Borders, who also founded Borders Books.)

Two decades later, Instacart, a similar business to Webvan, has gone public and boasts a $7B+ market cap. Timing is crucial.

I always ask myself: why now?

Both technology shifts (e.g., mobile, generative AI) and behavior shifts (e.g., newfound emphasis on sustainability, mental health being destigmatized) can have strong effects on a startup’s success. The best companies often combine both: Robinhood, for instance, brought trading to mobile just as mobile adoption was inflecting, but also rode the wave of post-recession, Occupy Wall Street-era interest in financial autonomy.

Another facet of market timing is entry valuation and exit valuation. This builds on last week’s point about paying nosebleed prices. The challenge with investing in a frothy category is that you’re typically overpaying at entry, and that category might not be as “hot” by the time you exit. You buy high and sell low, on a relative basis. This is why staying disciplined on entry price is crucial, even (or especially) amidst hype cycles.

To trot out another Bill Gurley quote, I like how he recently framed timing:

I went and talked to some LPs who have been in the business for a very long period of time. And a vast majority of the reason venture outperforms other asset classes has to do with these tiny windows where you have a super frothy market... If you strip those years out of a 40 year assessment, it’s actually not that interesting of an asset class. This highlights the need for venture funds to get liquidity at the peak. Right when we’re at the peak is when people get the most brazen and confident and start talking about how we're going to hold forever. You had venture firms with the biggest positions they’ve ever had in their entire life go over the waterfall and evaporate what could have been returns.

2021 was a great time to get liquidity. Unfortunately for many, they failed to exit at the peak. Many instead increased deployment pace at the peak, and will pay the price down the road when it comes time to exit.

“FOMO” investing is hard to avoid; investors can easily mistake activity (“Did we see the deal? Did we get into the hot round?”) for what matters—a few right decisions a year. We all have to unlearn bad habits of the frothy post-COVID years—which venture investors played a role in creating—and to be disciplined when it comes to price and respecting the power law.

One litmus test I use to test my conviction is asking myself:

“If I had made an investment last week, would I still want to make this investment?”

This forces me to question whether I’m leaning in out of pressure to get a deal done—which we all feel—or whether I actually believe in this founder and opportunity. A related question, “Would I still want to support this founder even if things aren’t going well?” That tests depth of belief in the entrepreneur and what they’re building.

Market Dynamics

Different markets have different dynamics. Some markets are winner-take-all, some are winner-take-most, and some support many large players. Some markets have natural barriers to entry, and some don’t. Some markets are capital intensive (which will dilute early investors), and some aren’t. It’s important to study a market and understand whether it’s compelling for a newcomer.

This leads into business model. There are only so many business models that can support a $1B+ revenue business. There’s a reason that marketplaces and SaaS are so popular in venture capital; when they work, they’re a beautiful thing. I tend to avoid markets that have structurally low margins or rely heavily on paid marketing.

Business model goes hand-in-hand with product, so let’s transition to that topic.

Product: Platforms & Networks

At Daybreak, we focus on the application layer of technology; we don’t do infrastructure. We look for internet and software products that have the potential for viral adoption, and our job is to help our entrepreneurs realize that potential.

This means that we invest in a lot of marketplaces, a lot of consumer internet businesses, and a lot of bottom-up software products—categories that typically have viral adoption and often a compelling network effect or platform dynamic.

That last part is key. Networks and Platforms.

As capital has flowed into venture the past few years—and as the market became overheated—investors started investing in too many product companies. Product companies can be nice businesses, but they’re rarely the fund-returners that the portfolio construction math shows us we need.

“Networks” and “Platforms” are overused buzzwords in venture, and they have some overlap. I’ll take a stab at simplistic definitions.

I think of networks as companies that compound with each additional customer. Those customers typically power viral loops that drive organic distribution, and the strength of the network over time creates a formidable moat for the business. This is the classic network effect that we’re taught—it applies to social networks like Facebook (more friends on Facebook makes it a better experience for me), marketplaces like Airbnb (more hosts and more guests make Airbnb better for all of us), and content networks like TikTok (each new piece of content improves what my FYP can show me and fine-tunes TikTok’s algorithm). Networks are more complex and varied than this lets on, but you get the point.

I think of platforms as companies that enable ecosystems to form on top of them. While a product might solve a single problem, a platform weaves together multiple products solving multiple problems. Take Shopify. Shopify lets you launch an online store, sure. But Shopify also handles order management, inventory management, and shipping. Shopify even has a robust App Store with 8,500+ apps that merchants can use.

Apple used to be a product company, churning out iPods and MacBooks. But Apple has transitioned to a platform company—the iTunes Store in 2003 and the App Store in 2008 were key steps to building an ecosystem of interconnected products.

Many generational companies are networks and platforms.

Amazon, of course, is a marketplace connecting shoppers and brands. But Amazon is also the foundation underpinning a robust third-party seller marketplace, and offerings like Fulfilled By Amazon (FBA) are now crucial capabilities in Amazon’s arsenal.

Faire has built a holistic operating system for independent retailers and brands—everything from discovery to underwriting to returns is handled by Faire, which becomes the central nervous system for these small businesses.

One of my favorite companies is Roblox. Roblox is a social and content network—a place for users to connect, one that gets stronger with each additional user.

And Roblox is also a developer platform, with ~400,000 monetizing developers building experiences for Roblox. I made this graphic way back in 2020, but it still holds—and the flywheel continues to spin faster and faster over time:

When I think of the difference between product companies and platform companies, I often think of productivity software. Loom is a wonderful product; I’m a power user. But Loom has largely been a product, a tool used across Slack and Gmail. It never became the source of truth for an org, the knowledge database. Figma, meanwhile, has expanded into a broad ecosystem built around design (and now even beyond design), and the Figma Community has thousands of plugins and templates and widgets. The product vs. platform distinction is a reason Loom is being acquired by Atlassian for $975M and Figma by Adobe for $20B. Loom is still an incredible success for its founders, for many employees, and for early investors. But later investors won’t make out so well, and realizing a platform vision would’ve increased the company’s value.

Or take an example in vertical SaaS. Say you build software for veterinarians. Maybe you build a scheduling system that lets vets book their customers. You charge $10 a month. Over time, a dozen other vet booking systems emerge and competition erodes prices down to $5. Switching costs are low, you have no leverage, and your margins wither away.

Now say that you instead build the scheduling software, but you quickly integrate payments—all the dollars are flowing through your software. You add a network component where vets can chat with other vets, where customers can chat with other customers, and where people can even upload profiles for their pets with health records across various vet clinics. All of a sudden, your tendrils have worked their way into every facet of the veterinary ecosystem; good luck ripping out your software now.

Some of the best early-stage investors have been writing about this for decades—check out some of Fred Wilson’s and Bill Gurley’s writings from the 2000s and early 2010s. I think Fred has a piece similar to the SaaS example above. This isn’t a new playbook, and it’s of course easier to write about than to execute. Platforms are enormously difficult to build. But look at the tech companies that have been successful over the past few years: Figma and Unity, Faire and Rippling, Airbnb and DoorDash. They’re networks and platforms, often both, and they prove that value accrues to complex, interwoven ecosystems of products.

AI is making every company vulnerable. The product companies are especially vulnerable; they have no moat. It’s much harder to disrupt a robust network or platform, and those companies are the ones to look for when investing at early stage.

Founder

A great market and a great product are, well, great. What investor wouldn’t want them? But at the end of the day, in early-stage venture it’s all about the founder.

We’ve seen this play out this week with Sam Altman and OpenAI. A founder is a company’s DNA; for most businesses, removing the founder nullifies what makes the company unique and compelling.

Investing at Pre-Seed and Seed is about understanding people—intuition. This is what makes early-stage investing more an art than a science.

The best entrepreneurs share a few traits in common. To cover three of them here:

Founder / Market Fit

“Founder / Market Fit” is an overused term in VC. But it does matter. The question I always ask myself is:

“Why is this founder the founder to build this business?”

And I often ask the founder:

“Out of everything you could be working on, why this?”

The best founders have unique work experiences or lived experiences—sometimes both—that give them unfair advantages to build their business. Take Jack Conte of Patreon. Jack’s a Stanford grad, yes, but he was a musician who experienced firsthand how hard it is to earn a living on YouTube. He built Patreon for people just like him.

The entrepreneur I wrote about in The Resale Revolution a few weeks back is special because she built B2B2C commerce product in the past, yes, but also because she lives and breathes secondhand—she knows the pain of spending her Saturday cataloging items on Poshmark and messaging buyers on Depop. She understands the pain-points intimately, and as a result is the person who knows how to build a better solution.

Clarity of Thought

The best founders can articulate exactly what needs to be built, and when. I often ask two questions:

What needs to be built in the next six months?

This is to see how deeply they understand the order of operations for the near future. Even if you’re building a complex network or platform, you’re typically starting with something specific—often a product that solves the most salient painpoint for the user. The early days are sniper-like. Complexity can come later. Articulating that early focus is key.

The follow-up question zooms out:

If everything goes according to plan—green lights all along the way—what will you have built in five years?

This is the opposite—can that near-term plan feed into a long-term vision? How do the pieces fall into place? What’s the master plan? Another question I like:

What keeps you up at night?

I find this reveals a founder’s depth of understanding of their market and product. I love when a founder knows what they don’t know, and isn’t afraid to share that. It gives me confidence that they also know what they know, and that they have self-awareness of their blindspots.

X-Factor

Some investors like the word “killer” when assessing a founder. Is this person a “killer”? And I find that the word does help—it susses out whether a founder has a certain ambition and grit. But I prefer the term “x-factor.”

Killer can capture a bit too much of the Silicon Valley founder stereotype: hard-charging, aggressive, typically white, typically male. The Travis Kalanick type in HBO shows. And female-founded companies are consistently underfunded, partly because of these stereotypes and biases; from the same data source as last week’s State of the Seed data:

Of the four investments we’ve made at Daybreak, two are led by female founders. We aim to maintain that parity. And by the way, the best female founders are killers. But I still prefer the term x-factor, which is more flexible and less charged; there are many shades of entrepreneur out there.

X-factor captures a founder’s tenacity—the steeliness behind her eyes that shows she’ll run through walls to build a generational company.

Two talented founders I work with, for instance, saw COVID completely wipe out their revenue. They started again from scratch, with a new target customer, and rebuilt the business to over a million of ARR within a year. That’s the x-factor.

An earlier-stage founder I met recently built his business to $1M of run-rate GMV as a one-man-band, before going out for his first institutional round. When I looked up the company on Reddit to see customer feedback, dozens of people had written, “Their customer service is great—the rep I spoke with, Evan, was so helpful.” Evan is the CEO and founder. (I changed his name here.) I was blown away by his hustle.

One question I like to ask myself is:

Could this founder build a big business without me?

An investor’s job is to increase the odds of success; if I do my job right, your probability of a $5B+ outcome should go up a little. But the investor’s job isn’t to tell the founder how to run the company. The best founders know how to execute.

Another important question:

Would this founder still build this company if they couldn’t raise capital? (Or if they couldn’t raise capital from a top firm?)

In other words, are they a tourist, or are they set on willing this company into existence because they believe so deeply in its mission and value.

Final Thoughts

Venture sales cycles are long. Very long. It can be tempting to get caught up in the hot deal of the week. This was especially hard to resist in 2020 and 2021, when firms rewarded investors for moving quickly, for seeing deals, and for winning. The best investors had the discipline to step back from the hype cycle and remain focused on the big picture: early partnership and good ownership in generational companies. One of my mentors at Index often told me, “My career will be defined by three companies—by three decisions.” This is a job about a few right decisions over many years.

Being early often means being contrarian; if everyone is excited about a company, that excitement may be priced in, or everyone might just be feeding into a self-reinforcing, herd-mentality-driven hype cycle. There’s very little original thought in this industry (or in any industry, for that matter) but this is an industry that rewards originality and conviction.

For many founders, venture isn’t the right product. For many founders, it might be preferable—and likely more economically rewarding—to bootstrap or raise a small round, then hit profitability.

Venture is structurally built for moonshots. It’s not like private equity, or even the growth world. It’s predicated on the power law, on high loss ratios, on what can go right. This emphasis on growth puts pressure on companies and founders. When things work, everyone’s happy, but raising venture means an expectation of outsized returns.

But the asset class is a unique one: Seed funding pours fuel on the spark of entrepreneurship. Since 2001, 53% of all IPOs, and 70% of tech IPOs, raised venture funding. Apple raised venture funding. So did Google. So did Facebook and Nvidia and Amazon. When venture works, it really works. Ideas get turned into companies, and those companies transform markets, shift culture, and change everyday life.

Additional Reading

I’ve always enjoyed the writings of Fred Wilson, Bill Gurley, Josh Kopelman, and Rick Zullo on Seed investing. They’ve taught me a lot, and they’re what got me into this business. Check out their oeuvres for more on this topic.

Related Digital Native Pieces

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: