Weapons of Mass Production

What the Industrial Revolution Was to Physical Production, the AI Revolution Is to Digital Production

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 60,000 weekly readers by subscribing here:

Weapons of Mass Production

Post Malone is having a good month.

The artist was featured on Beyoncé’s new album Cowboy Carter in the song “LEVII’S JEANS.” And in a few weeks, Post Malone will feature again on spring’s other big release—Taylor Swift’s The Tortured Poets Department.

Post Malone’s feature on Tortured Poets comes in a song called “Fortnight,” and the song already leaked online. Well, not actually—but a lot of people were fooled into thinking so. An AI-generated version of “Fortnight” took TikTok by storm last month (it’s actually a banger) and duped everyone into believing the track leaked.

This is the world of AI: a song can be entirely generated—fabricated—but be plausibly, passably excellent. (The same thing happened with Swift’s track “Suburban Legends” last fall before the 1989 (Taylor’s Version) release, and many fans ended up preferring the AI version.)

Spotify reinvented music distribution. It put 100 million songs in your pocket. Generative AI will reinvent music production. There are a number of early-stage startups that let you toggle artist, genre, and ~vibe~ to create a wholly new work—e.g., “Create a Miley Cyrus breakup song with a sad, wistful feeling to it.” Of course, these companies will need to navigate the labyrinth of music rights, but some version of these tools feels inevitable.

This example embodies a broader shift we’re seeing from distribution ➡️ production.

Distribution vs. Production

The internet was a distribution revolution.

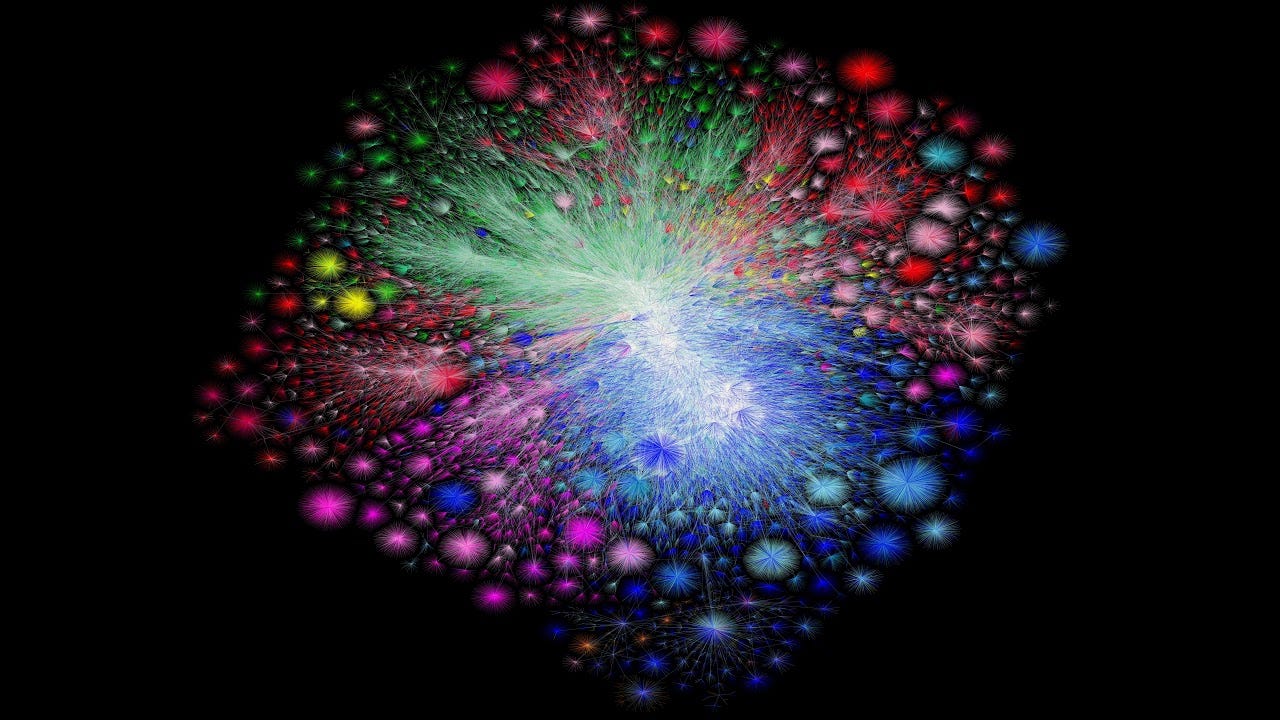

At its simplest, the internet is all about networks. You can even visualize those networks. Back in the 2000s, a man named Barrett Lyon used traceroutes (maps of how data travels online from its source to its destination) to create an image that showed internet activity circa 2003:

In 2021, Lyon updated his visualization. This time, rather than using traceroutes, he used Border Gateway Protocol routing tables to get a more accurate view. The updated image is composed of clusters of network regions—examples of clusters include the U.S. Department of Defense’s Non-Classified Internet Protocol Network, Shenzhen Tencent Computer Systems, and Amazon’s AWS. (You can watch a video of the visualization here.)

The internet is all about rails—rails for information, data, content, commerce, and communication 🛤️.

While the internet was a distribution revolution, AI is a production revolution. Generative AI makes it really, really easy to make stuff. It blows open the floodgates of production.

We’ve seen past technology eras for both distribution and production. The automobile was largely a distribution revolution—people could travel easily across long distances, which led to sprawling cities and offshoot industries like the shopping mall and the credit card. Products could also travel easily, giving way to the trucking industry and so on.

The Industrial Revolution, meanwhile, was a production revolution. Goods could be manufactured cheaply at scale. This paved the wave for the automobile revolution, of course; cars could be mass produced because of innovations developed during the Industrial Revolution (and later Henry Ford’s assembly line).

This time around, things are happening in reverse. We already had the distribution revolution with the internet; we have the rails for digital distribution. Now we’re getting mass digital production with AI.

This means we’re going to see an explosion in production tools.

The Tools of Production

The steam engine emerged in the early 1700s and mechanized factory production. All of a sudden factories didn’t need to be located on or near sources of water power. Manufacturing exploded.

What’s the digital equivalent of the steam engine? Arguably, the transformer model. Foundation models are the building blocks for a new era of production. Factories succeeded with economies of scale and with specialized production: you got really good at making buttons in this factory; you got really good at making wheels in that factory. It will be the same with models, which can be fine-tuned and trained for specific use cases—for legal briefs, for tax filings, for movies, for coding.

Some of the most exciting startups right now are startups that power digital production. In seconds, I can write this prompt in Midjourney and get beautiful artwork for this Digital Native piece:

“We are in a factory and there is an enormous conveyer belt powered by big machines. On the conveyor belt are a series of digital objects being produced. There are robots working at the conveyor belt. The vibe of the image is sleek and polished and futuristic. The style is cyberpunk. High-resolution, 4K.”

That would take a human artist hours to create.

It’s the same for video. Last month’s The Future Is a Dupe dug into OpenAI’s Sora, an AI model that can create stunning videos from text prompts. Here’s the video output for the prompt:

“Several giant wooly mammoths approach treading through a snowy meadow, their long wooly fur lightly blows in the wind as they walk, snow covered trees and dramatic snow capped mountains in the distance, mid afternoon light with wispy clouds and a sun high in the distance creates a warm glow, the low camera view is stunning capturing the large furry mammal with beautiful photography, depth of field.”

It’s gorgeous and cinematic, nearly movie quality. No need to hire a bunch of wooly mammoths to get the shot.

Similar to GPT models, Sora is a transformer. The model works using diffusion—basically, it creates a video that starts out looking like static noise, and then gradually transforms it by removing the noise.

More specifically, Sora uses patches. From OpenAI:

“We represent videos and images as collections of smaller units of data called patches, each of which is akin to a token in GPT. By unifying how we represent data, we can train diffusion transformers on a wider range of visual data than was possible before, spanning different durations, resolutions and aspect ratios.”

Sora was trained using videos and images (which are just single-frame videos) of various lengths, resolutions, and aspect ratios. OpenAI’s technical breakdown is worth reading if you’re interested in more nuances of how Sora works.

This week, OpenAI revealed a new tool called “Voice Engine” that can clone a person’s voice with just a 15-second recording. The production tools keep coming. Startups like HeyGen (video + audio) and ElevenLabs (audio) are also growing quickly. allowing anyone to spin up moving and talking avatars. (When I play around with the tools they always seem a bit uncanny valley, but they’re still impressive.)

We’re racing towards a future in which anyone can make their own movie or TV show in a matter of seconds (provided they have a script). I uploaded my headshot to Midjourney and asked it to re-create me in the style of Family Guy. How long until I can create my own entire Family Guy episode?

This is the power of AI. The tools are even generous enough to give you an extra 20 pounds of muscle. What’s not to like?

Their blackbox nature, for one. The inner-workings of these tools are more difficult to see and appreciate than the inner-workings of a steam engine—at least with steam engines there are physical components to observe. Transformer models are more mysterious, and we’re still learning about them. (Both Sora and Voice Engine are closed to the public as OpenAI explores how to safeguard the technologies; with Voice Engine, the company is exploring watermarks for synthetic voices, for instance. This feels especially pressing as 2024 may be our first Deepfake Presidential Election.)

But just as a past generation of physical tools fueled the mass production of physical products, a current generation of digital tools will fuel the mass production of digital products.

The best tools have two things in common:

They make production 10x easier ✅, and

They make production 10x cheaper ✅.

In doing so, they:

Lower the bar for skills ✅, and

Lower the bar for access ✅.

More people can make stuff (1) quickly and (2) cheaply; you don’t need a whole production studio or specialized knowledge. Software has already bent the curve here: many Oscar-winning movies are now edited on Apple’s Final Cut Pro 2, software that costs $299 and that even a woefully untalented person like me can—and does—use to edit mediocre home videos. But AI takes things to a new level, almost removing entirely the need for skills or money.

Some of the biggest companies from the last 20 years were built around the internet unlocking distribution.

I expect some of the biggest companies of the next 20 years will be built around AI unlocking production.

Business Models for Production

When it comes to distribution, all roads lead to advertising.

Distribution is about getting eyeballs at scale, which dovetails perfectly with ads. As a result, many of the biggest networks are ad-based: Google, Facebook, Snapchat, YouTube, TikTok.

Spotify gets about 15% of its revenue from ads, and even Netflix, the poster-child for consumer subscription, is riding the ad train—the ad-based tier is by far Netflix’s fastest-growing tier, responsible for about 30% of new sign-ups.

And just this week, Discord—which has long eschewed advertising in favor of its Nitro premium subscription model—announced that it’s finally leaning into advertising. When it comes to distribution, which is all about aggregation, you just can’t escape ads.

But when it comes to production, ads don’t make as much sense. My view is that the dominant business model for production tools will be a freemium model. You’ll get some amount of production for free, above which you’ll have to pay.

You might have to pay a flat subscription, but I suspect more common will be a credits-based system. This ensures that payment is tethered to volume (and thereby underlying costs of generations), with some people generating much, much more than others. You might get your first 10 credits free, enough for a 60-second video clip. To get another 10 credits and another 60 seconds, you’ll need to pay $9.99. Or maybe I can feed a voice generator a 100-word script for free, but I have to pay another few bucks for every additional 100 words. You get the point.

This will be the predominant business model of digital production. Ads aren’t going anywhere, and they’ll continue to dominate monetization for the rails of distribution, but the tools for production will price based on units of production.

Cultural Ramifications

A couple years back, there was a viral Twitter thread that lamented how bland modern architecture has become.

Architecture, the thread argued, used to be full of intricate detail and craftsmanship. Now it’s void of any care or feeling. Lampposts used to be ornate; now they’re plain and ugly. Same for benches, houses, schools, even light switches.

A TikTok I saw last week made the same point with lighters. Antique lighters are gorgeous; contrast them with cheap plastic contemporaries. What happened to artistry?

The takeaway is clear: mass production erodes artistic love and care.

We could make the same argument in cinema. Box office hits used to be Oscar-winning dramas and witty comedies; now they’re Marvel movies and sequels. Did cheaper production and better distribution destroy quality?

I’d argue that production simply leads to more. The quality is still there, but the average is dragged lower. This makes us think everything is worse, but that isn’t the case. The best buildings and movies and TV shows are just as good, if not better; we just get distracted from the masterpieces by McMansions or Dr. Pimple Popper. The situation isn’t as dire as it seems. In fact, more people are able to make more great stuff.

But I expect over the next few years, this will become a common critique. “Remember before AI,” we’ll lament, “when things used to be made with care and precision by real artists?” But this argument rhymes with the same arguments that took place when theater gave way to film, when film gave way to TV, when TV gave way to YouTube. The internet removed gatekeepers, meaning that any painter or filmmaker or musician or creator could break through on her own merits. That was a distribution revolution, and it was a great thing. The rails are now there, and a production revolution will broaden access to the proper tools.

A more poetic view is that more great things get made by people not from central casting. The visual effects team on Everything Everywhere All At Once, last year’s quirky Best Picture winner, used the AI tool Runway on the film. It’s one reason that the movie was able to be made with just seven people (five full-time, two contracted) on the VFX team.

To use an even more recent example, this year’s winner for Best Visual Effects at the Oscars was Godzilla Minus One—a film with a measly $15M total production budget. It beat out competitors like Mission Impossible 7 and Guardians of Galaxy 3, which had $300M and $250M budgets, respectively. Damn.

That’s impressive stuff, and the internet noticed:

This wouldn’t happen without modern software and AI tools. And with the next generation of AI production tools, we can all make great stuff. Instead of having a bland chart as the cover image for a Digital Native piece, I’ve been largely using Midjourney, which makes me at least seem artsy and cool. And soon enough, I might be able to spin up that Family Guy episode, using my own script and starring that questionably-buff cartoon Rex from above.

Final Thoughts

What the industrial revolution was for atoms, the AI revolution is for bits. The difference is: bits are a lot more scalable than atoms, and they’re coming after a distribution revolution that allows us to direct those bits all over the world. This means that this revolution will happen fast. Expect lots of deepfakes and truth-questioning, a tsunami of AI images and videos and shows and movies, and the rise of user-generated generated content. We’d all better strap in as the next wave of mass production begins.

Related Digital Native Pieces

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: