The Future Is a Dupe

Sora, Vision Pro, and the Blurred Lines Between Truth & Fiction

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 55,000+ weekly readers by subscribing here:

The Future Is a Dupe

Gen Z goes crazy for a good dupe.

What’s a dupe exactly? Short for “duplicate,” a dupe is basically a cheaper version of a pricey product. In other words, a knock-off.

Prada Thick Frame Sunglasses will run you $385. Dupe bloggers will instead point you to Nasty Gal Factory Bueller II Shades, which look basically the same but will set you back just $20. A Chloe Fay Shoulder Bag costs $1,790. But any dupe-savvy shopper knows you can get the Forever 21 Faux Leather Chain Crossbody—a Chloe Fay dupe—for just $25. And so on; you get the picture.

Gen Z, always on the hunt for a good deal, is dupe-obsessed. TikTok is teeming with creators suggesting savvy dupes for the cost-conscious consumer.

When I did the Vision Pro demo at the Apple Store recently, all I could think about were dupes. Virtual reality is, after all, one giant dupe of reality.

In this image here, a man uses his Vision Pro to experience a panorama of Iceland, originally shot on an iPhone. This specific panorama is actually part of Apple’s in-store Vision Pro demo, which I recommend doing—you can book the demo here. Your Apple Store guide will instruct you to adjust your level of immersion until you’re inside the panorama, standing on an Icelandic glacier.

Naturally, the experience is stunning. More on Vision Pro later (spoiler alert: I’m a big fan).

I left the demo thinking about dupes of reality: the worlds of the physical and digital are blurring so that every “real life” experience will soon have its digital dupe. What are the repercussions of that?

MKBHD poses an interesting question:

The goal of this week’s piece is to explore what happens when our analog world gets its digital dupe.

Sora & Vision Pro

Applications: Dupes of People, Places, and Things

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

Let’s dive in.

Sora & Vision Pro

In my mind, February 2024 will go down in technology history for two landmark introductions: OpenAI’s Sora and Apple’s Vision Pro.

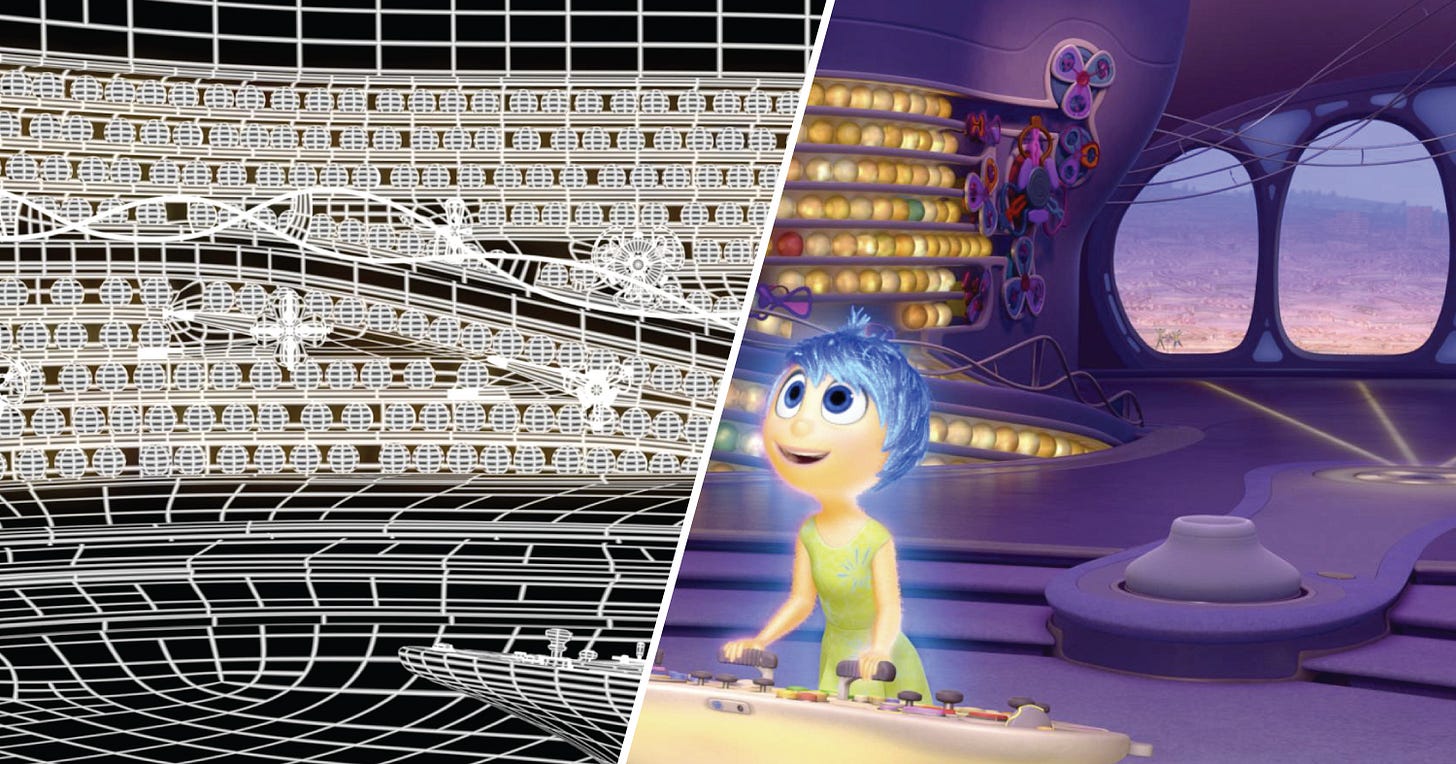

Last August’s The Future of Technology Looks a Lot Like Pixar predicted a future in which we’ll all be able to render gorgeous films in seconds—well, not render, but generate. In this future, we’re all Pixar-level animators. Powerful creative tools are accessible to everyone.

That piece started by discussing the creation of the Alliance for OpenUSD. Apple, in preparation for its Vision Pro launch, announced last summer that it was partnering with Pixar, Nvidia, Adobe, and Autodesk to create a new alliance that would “drive the standardization, development, evolution, and growth” of Pixar’s Universal Scene Description (USD) technology.

USD is a technology originally developed by Pixar that over time became essential in building 3D content. Essentially, USD is open-source software that lets developers move their work across various 3D creation tools, unlocking use cases ranging from animation (where it began) to visual effects to gaming. Creating 3D content involves a lot of intricacies: modeling, shading, lighting, rendering. It also involves a lot of data, but that data is difficult to port across applications. The newly-formed alliance effectively solved this problem, creating a shared language around packaging, assembling, and editing 3D data.

In Nvidia’s words: “USD should serve as the HTML of the metaverse: the declarative specification of the contents of a website.” (Side note: it’s rare you find a major company still using the m-word.)

That August piece then explored how Vision Pro would intersect with generative AI to supercharge the things we create and experience. Fast forward six months, and that future is arriving a lot sooner than I, and many others, had anticipated.

Sora

Earlier this month, OpenAI announced Sora, an AI model that can create stunning videos from text prompts. Sora is best illustrated with some of the examples OpenAI offered (the technology isn’t yet publicly available but OpenAI’s examples are here):

Prompt: “Animated scene features a close-up of a short fluffy monster kneeling beside a melting red candle. The art style is 3D and realistic, with a focus on lighting and texture. The mood of the painting is one of wonder and curiosity, as the monster gazes at the flame with wide eyes and open mouth. Its pose and expression convey a sense of innocence and playfulness, as if it is exploring the world around it for the first time. The use of warm colors and dramatic lighting further enhances the cozy atmosphere of the image.”

Prompt: “An adorable happy otter confidently stands on a surfboard wearing a yellow lifejacket, riding along turquoise tropical waters near lush tropical islands, 3D digital render art style.”

Prompt: “A cartoon kangaroo disco dances.”

Pixar films typically take about four years to make. Pixar has said it takes around 24 hours to render a single frame, and that there are 24 frames per second. For a 100-minute movie, that means it would take 400 years to render. Of course, Pixar has many machines working together in concert—around 2,000 machines in total, making Pixar one of the 25 largest supercomputers in the world.

Yet the cute animals in the three Sora outputs above could be straight out of a Pixar film, and they were created with just a single paragraph—or, in the case of the third example, with just five words. Right now, Sora can output videos up to 60 seconds in length, but it’s only a matter of time before we’re seeing full-length features made at the drop of a hat.

Of course, Sora does a lot more than animation. A few examples for “real life” scenes:

Prompt: “A stop-motion animation of a flower growing out of the windowsill of a suburban house.”

Prompt: “The camera directly faces colorful buildings in Burano Italy. An adorable dalmation looks through a window on a building on the ground floor. Many people are walking and cycling along the canal streets in front of the buildings.”

Prompt: “A stylish woman walks down a Tokyo street filled with warm glowing neon and animated city signage. She wears a black leather jacket, a long red dress, and black boots, and carries a black purse. She wears sunglasses and red lipstick. She walks confidently and casually. The street is damp and reflective, creating a mirror effect of the colorful lights. Many pedestrians walk about.”

Incredible.

Why would someone hire a model and camera crew, then fly them to Tokyo, when they could spin up that last video in seconds?

It’s easy to see the earthquakes heading for media. The filmmaker Tyler Perry had been planning an $800M expansion of his Atlanta studio, including 12 new soundstages for his productions. But after seeing Sora last week, Perry told The Hollywood Reporter that he’s now halting that expansion:

“Being told that it can do all of these things is one thing, but actually seeing the capabilities, it was mind-blowing.

“I no longer would have to travel to locations. If I wanted to be in the snow in Colorado, it’s text. If I wanted to write a scene on the moon, it’s text, and this AI can generate it like nothing. If I wanted to have two people in the living room in the mountains, I don’t have to build a set in the mountains, I don’t have to put a set on my lot. I can sit in an office and do this with a computer, which is shocking to me.

“It makes me worry so much about all of the people in the business. Because as I was looking at it, I immediately started thinking of everyone in the industry who would be affected by this, including actors and grip and electric and transportation and sound and editors, and looking at this, I’m thinking this will touch every corner of our industry.”

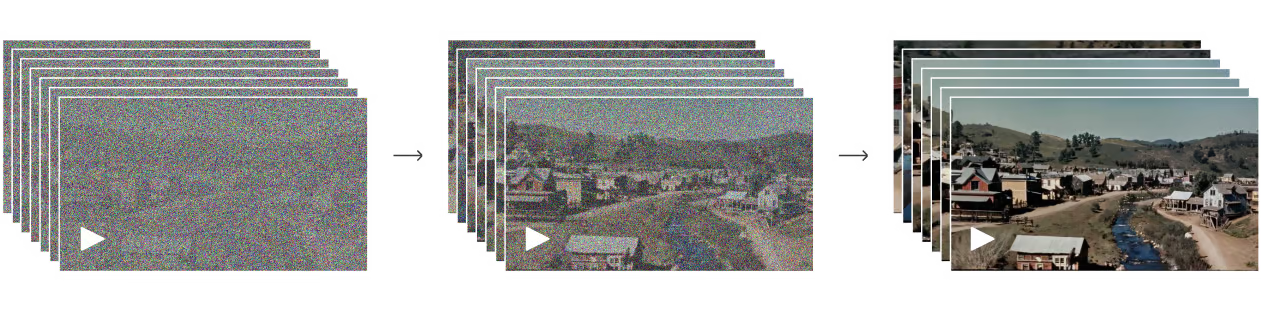

Similar to GPT models, Sora is a transformer. The model works using diffusion—basically, it creates a video that starts out looking like static noise, and then gradually transforms it by removing the noise.

More specifically, Sora uses patches. From OpenAI:

We represent videos and images as collections of smaller units of data called patches, each of which is akin to a token in GPT. By unifying how we represent data, we can train diffusion transformers on a wider range of visual data than was possible before, spanning different durations, resolutions and aspect ratios.

Sora was trained using videos and images (which are just single-frame videos) of various lengths, resolutions, and aspect ratios. OpenAI’s technical breakdown is worth reading if you’re interested in more nuances of how Sora works.

Vision Pro

To me, the most interesting part of the Vision Pro demo was how carefully the Apple Store employee avoided the term “virtual reality.”

“This is not virtual or augmented reality,” he said at one point. “It’s a new paradigm: spatial computing.” It’s clear that Apple wants its new device to be more than an entertainment gadget. A word cloud of the demo would probably reveal “computing” as the most-spoken word.

Apple has a long history of pioneering how we interact with technology. The Lisa and the Macintosh, released in 1983 and 1984, brought the graphical user interface to the masses. A GUI is how you and I interact with computers—the pointers, icons, windows, scroll bars, and menus that we’re all accustomed to on our screens. It’s hard to imagine now, but before GUIs you had to input a C:> prompt to interact with a computer. Apple came up with concepts like files, folders, and trashcans; created windows for different applications; and decided that tasks could be layered on top of one another.

With the iPhone, of course, Apple introduced a novel form of touchscreen. And with Vision Pro, Apple gives us eye tracking.

The highlight of the demo is the immersive experiences. You can watch kids in Africa play soccer as rhinoceroses roam the field; you can watch a woman balance on a high-wire tightrope in a canyon; you can dive with sharks. The entire experience reminds me of one of my favorite Tim Sweeney quotes: “I’ve never met a skeptic of VR who has tried it.” Yet when it came to reading an article or doing email, I found myself longing for my MacBook.

Using Vision Pro solidified to me that the device will, in the near term, be more of a console-like entertainment device than an iPhone-like mass market product—both in terms of use case and in terms of number of sales. Maybe that’ll change as the price drops and as the device becomes more aesthetic and more lightweight. Maybe killer apps will emerge that turbocharge Vision Pro sales. But for now, I expect “spatial computing” will be remain a relatively niche concept.

Applications: Dupes of People, Places, and Things

Most of AI’s attention—and value—has so far accrued to the infrastructure layer.

Nvidia announced earnings last week and beat Wall Street expectations—$24B in revenue, +265% year-over-year, and $12.3B in net income, +769% year-over-year (!). The stock soared, eclipsing $2T for the first time less than a year after first joining the $1T club.

In tandem, WIRED’s Lauren Goode had a great interview with Nvidia’s Jensen Huang. Huang underscored the pace at which AI is moving:

“If you look at the way Nvidia’s technology has moved, classically there was Moore’s law doubling every couple of years. Well, in the course of the last 10 years, we’ve advanced AI by about a million times. That’s many, many times Moore’s law.”

Huang goes on to explain how Nvidia underpins various AI applications:

“We’re not an application company, though. That’s probably the easiest way to think about it. We will do as much as we have to, but as little as we can, to serve an industry. So in the case of health care, drug discovery is not our expertise, computing is. Building cars is not our expertise, but building computers for cars that are incredibly good at AI, that’s our expertise. It’s hard for a company to be good at all of those things, frankly, but we can be very good at the AI computing part of it.”

So what will the generational applications be? If the infrastructure layer is taking shape, what apps come next?

As Sora and Vision Pro illustrate, we’re in the early innings of multiple, interlinking eras in technology. AI’s application layer is just beginning to crystallize; the defining companies of this generation will be built in 2024, 2025, 2026.

And spatial computing—to use Apple’s language—is also coming into view. New apps will be built for this medium.

To return to dupes, everything is about to get a dupe. What are the startup opportunities?

AI agents for consumers (dupes of people; someone for us to talk to)

AI agents for enterprises (dupes of people; someone to help out with work)

Immersive content (dupes of places & experiences)

New tools for building person/place/thing dupes and new rails for distribution

In Vision Pro, places get a dupe. You can explore Yosemite and almost feel as though you’re there. You can be part of an immersive story, a new medium. Scorsese and Spielberg mastered the art of the two-dimensional story you view on a screen; who will be the Scorseses and Spielbergs for this new format? And if YouTube and TikTok dominated two-dimensional video, what platform becomes the hub for spatial experiences or for AI-generated stories?

AI is creating dupes of people. On Character, of course, you can chat with facsimiles of Albert Einstein or Taylor Swift. That’s a consumer use case. But we’re also getting AI agents in the enterprise. Sierra, the new company from former Salesforce co-CEO Bret Taylor, is building agents for businesses to use. Use cases range from customer support to account management. Established tech players also have their own agents—Salesforce, for instance, has an agent called Einstein.

Successive technologies have steadily increased the amount of human communication. Radio. Telephones. Television. The internet. More and more…talking.

We’ve increased communication with strangers. A hundred years ago, you got customer service help from the woman behind the counter. Fifty years ago, you got customer service help from a voice on the other end of the phone. Ten years ago, you got customer service from the frustratingly slow-responding human on the other end of the instant message chat (looking at you, United Airlines).

I expect the next wave of technology will increase communication with non-human—in other words, chatbots and agents. If in 2023 we spoke 1 trillion words to AIs, by 2033 it’ll be 10 or 50 or 100 trillion. Get ready for a lot of conversational AI.

Final Thoughts: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

Technological progress has positive externalities and negative externalities. As the tech philosopher Marshall McLuhan said, “We shape our tools and thereafter they shape us.”

Virtual reality as a dupe of reality sounds dystopian. Isn’t it better to visit Yosemite in real life than to experience it through a headset—even if the latter means you can get your work done in the middle of the park?

Of course the real thing is better. But not everyone lives in northern California or has the resources to visit. In fact, less than half of Americans (48%) fly on a plane each year. About 4 in 10 Americans have never left the country—and 63% of those people say that an international trip is unaffordable. These statistics are for America, the wealthiest nation on Earth.

Here’s Marc Andreessen a couple years ago, explaining the concept of Reality Privilege:

“Your question is a great example of what I call Reality Privilege. This is a paraphrase of a concept articulated by Beau Cronin: ‘Consider the possibility that a visceral defense of the physical, and an accompanying dismissal of the virtual as inferior or escapist, is a result of superuser privileges.’ A small percent of people live in a real-world environment that is rich, even overflowing, with glorious substance, beautiful settings, plentiful stimulation, and many fascinating people to talk to, and to work with, and to date. These are also *all* of the people who get to ask probing questions like yours. Everyone else, the vast majority of humanity, lacks Reality Privilege—their online world is, or will be, immeasurably richer and more fulfilling than most of the physical and social environment around them in the quote-unquote real world.

“The Reality Privileged, of course, call this conclusion dystopian, and demand that we prioritize improvements in reality over improvements in virtuality. To which I say: reality has had 5,000 years to get good, and is clearly still woefully lacking for most people; I don’t think we should wait another 5,000 years to see if it eventually closes the gap. We should build—and we are building—online worlds that make life and work and love wonderful for everyone, no matter what level of reality deprivation they find themselves in.”

For many people, Vision Pro’s experiences may be the closest they ever come to a safari or hot air balloon ride or scuba trip. This is sad, but it’s also exciting and beautiful.

New technologies naturally come with fear and trepidation. AI is scary in many ways. It’s clear that technology companies are working in overdrive to allay concerns. Microsoft’s Super Bowl ad for Copilot spent its first 30 seconds showing a variety of everyday people who list out their thwarted dreams. In the second half of the ad, Microsoft shows how Copilot brings those dreams to life. Self-serving? Sure. But also a more optimistic view on inevitable technological progress.

If everything is its getting its own dupe—whether in immersive 3D worlds or through generative AI—we can make sure that those dupes augment the natural world, solve problems, and make a life a little better.

Sources & Additional Reading

I liked these analyses of Vision Pro and Sora from Ben Thompson and from MG Siegler

Here is OpenAI’s technical explanation of Sora

Related Digital Native Pieces

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: