Surf's Up

The Biggest Waves Across Productivity, Jobs, Shopping, Health, and Social

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 55,000+ weekly readers by subscribing here:

Surf's Up

One of my mentors and former colleagues, Mike Volpi, once gave me a good framework for startups: startups are like surfing.

You have three components: you have the surfer, you have the surfboard, and you have the wave. The surfer is the founder, probably the most important element; if you don’t have a good surfer, good luck catching a wave. The board is the product. It matters, of course, though a savvy surfer can fine-tune her board over time. (A good surfer can also probably overcome a bad board, but not vice versa.) The more challenging element to control is the wave. What kind of wave are you gonna get?

From the early-stage venture perspective, the wave is the toughest variable; there are a lot of exogenous factors. Where are we in the cycle? How big will this market be? Is there a “why now” for this product? The wave is full of “known unknowns.”

There are technology waves and there are behavior waves—changes in the underlying tech and changes in the people who shape and use the tech. My friend Talia had a good recent interview with the futurist Ray Kurzweil. Kurzweil is a legend: back in 1999, he predicted that AI would pass the Turing Test—a machine’s ability to demonstrate intelligent behavior indistinguishable from that of a human—by the year 2029. Stanford was alarmed by his prediction, deciding to hold an international conference as a result; most AI experts at the conference concluded that Kurzweil was being far too optimistic. Fast forward to today, and it looks like we’ll actually beat that timeline—maybe as soon as next year.

How did Kurzweil get this right? He emphasizes that economists tend to forget that technological change is exponential. Things change a lot more dramatically—and a lot more quickly—than we expect.

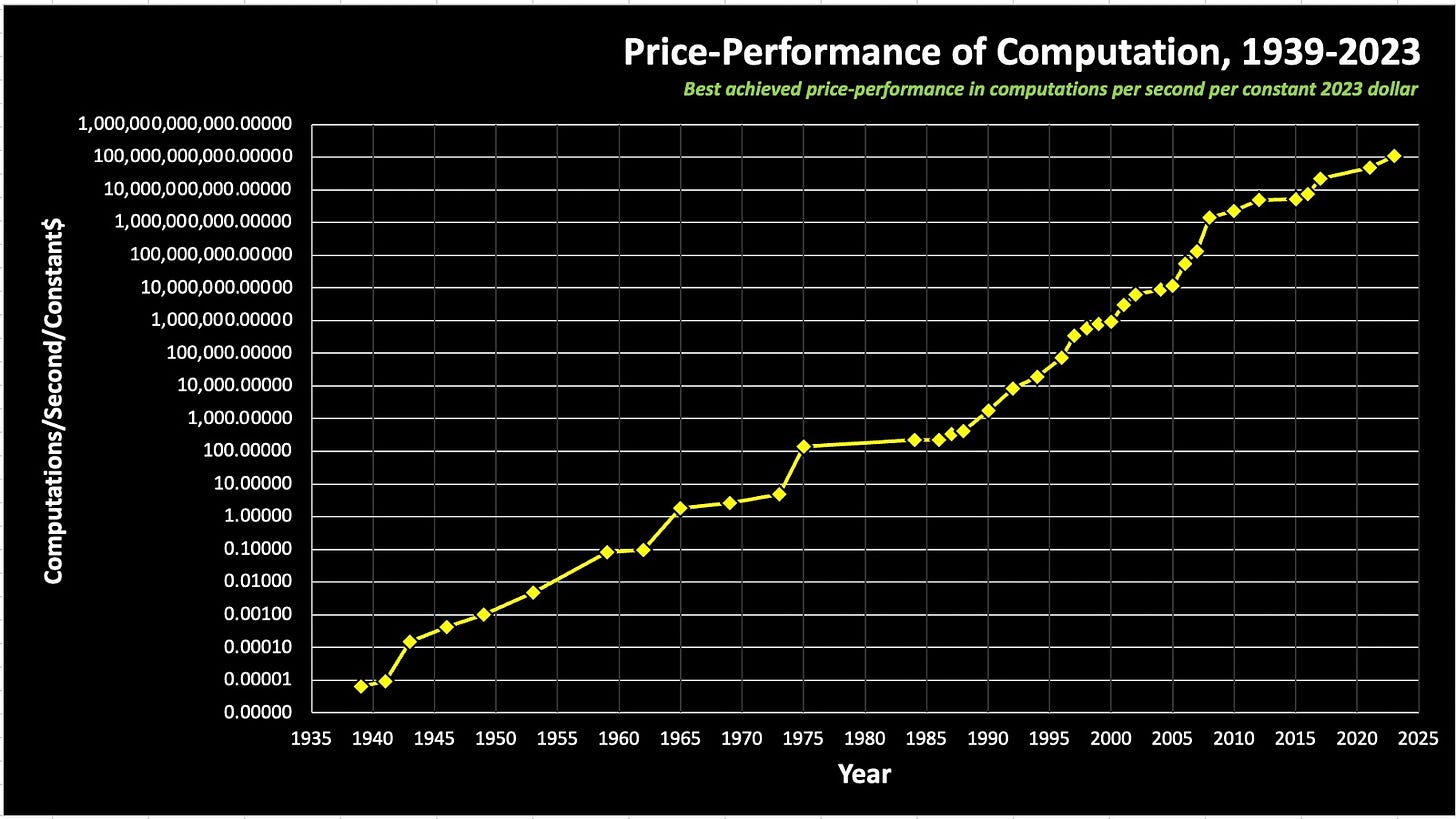

Here’s price-performance of computation over time; notice the y-axis is logarithmic:

This chart starts in 1931 with a German computer, which was presented to Hitler at the time (who saw no use in it). That computer did 0.000007 calculations per second per constant dollar. The chart ends with a modern-day Google computer that can do 65 billion (!) calculations per dollar. That’s a 20 quadrillion increase in the amount of computation for a dollar—for reference, a quadrillion has 15 zeros. As Kurzweil summarizes: “The exponential growth of computation is key to technology progressing.”

Clearly, exponential technological progress is a steady, ongoing wave—in some ways, a wave underneath the surface, in constant motion. There are additional waves sitting on top of this underlying current, including more specific technology waves: improvements in Nvidia chips, for instance, or Apple pioneering spatial computing with the Vision Pro. I’d call out the internet, mobile, and cloud as big waves from the past ~30 years.

We also see societal waves, which often show up in a new generation’s attitudes, behaviors, and worldviews. These have been the topics of past Digital Native pieces, primarily through the lens of Gen Z. Gen Z has shifting views on topics ranging from mental health, to sustainability, to careers, and those shifting views in turn drive change in the startup landscape.

It’s a useful thought exercise to explore the biggest “waves” in key segments of life and the economy. That’s the focus of this Digital Native piece. We’ll tackle five categories and examine what I find to be the most important wave in each—summed up in a single word.

Productivity = Augmentation

Jobs (and Finances) = Autonomy

Shopping = Circularity

Health = Tracking

Social = Latent Awareness

Let’s dive in 🏄🏼♂️

Productivity = Augmentation

My view on the future of work: we’re all about to get a lot of non-human coworkers.

These non-human coworkers will come in the form of AI agents, and many will have human names. Interfacing with Janet from accounting (the human) becomes interfacing with Janet the AI, who helps you log your expenses. Bugging Bob from IT (the human) for a laptop becomes chatting with Bob the chatbot for IT help.

This week, the startup Cognition introduced Devin, who they call “the first AI software engineer.” Devin is remarkable. He has successfully passed engineering interviews from leading AI companies, and he’s already completed real jobs on Upwork. When evaluated on the SWE-Bench benchmark, Devin outperforms previous state-of-the-art model performance:

For today’s college kids, who will enter the working world in the next few years, working with AI “co-workers” will become second nature. This embodies the biggest wave in productivity: augmentation. The best tools will augment what humans can do. You could argue that software digitized, bringing offline workflows online and in the process making them more efficient, while AI truly augments. Kurzweil points out that technology has already surpassed human ability:

“Take some obscure philosophy problem…and [AI] can write you a very intelligent essay about it and it takes about 20 seconds. No human being can do that. In fact, you can ask [the AI] anything and it can answer it pretty intelligently. No human being can do that.”

This continues a familiar pattern of technology amplifying humans:

“Technology is an extender of human thought. People are very concerned about us versus AI, as if it is an intelligence that comes from another planet. But it’s created by human beings. It’s based on human thought and it amplifies who we are. We should be enthusiastic about it because it’s amplifying who human beings are.”

Pop culture depictions don’t paint a rosy portrait, but hopefully we can mold more of an R2-D2 companion than a HAL 9000 antagonist.

Another great demo from the past week came from Hebbia, led by George Sivulka, the surfer in the right of the photo above. Hebbia announced Matrix, an LLM-native productivity tool. In a sample use case, Matrix can quickly analyze a fund’s portfolio of investments—arguably rendering a junior financial analyst obsolete.

We’ll all soon work with Devins and Evas and Rachels and Liams. We’ll use Matrix and other tools. Some AI agents might be engineers; others might be accountants or designers or financial analysts or work in HR.

My friend Will noticed that “minutes worked” is a metric that Devin shares with users. This gets to a recurring topic on Digital Native—new possible business models for AI companies. AI companies may sell their software as work completed rather than with traditional SaaS pricing. If the average software engineers costs you $100K+, but Devin renders her moot, then that’s a pretty lucrative pricing strategy.

Jobs (and Finances) = Autonomy

Millennials and Gen Zs aren’t very invested in their jobs.

A study from Gallup found that the share of Millennials “actively engaged” in their work fell from 39% to 32% over the past four years. For Gen Zs, that figure dropped from 40% to 35%. The word to summarize the wave in jobs could be “nihilism.” But a more optimistic interpretation, I think, is “autonomy.” People want more control. They want different kinds of work, kinds with more agency and self-direction.

Last week’s Business-in-a-Box 2.0 drove this point home: the next doctor or nurse or therapist or architect or esthetician is more likely to be self-employed, with her entire career facilitated by a vertical SaaS platform. The technology is there, and now the behavior is there. From last week’s piece:

“People want to be their own bosses, masters of their own destinies. Young people, in particular, grew up watching parents and grandparents lose jobs during the 2008 financial crisis and again during the pandemic. As a result, a new generation has come of age prioritizing self-reliance.”

The challenge with Business-in-a-Box is the question: how many people want to think like owners? People say they want to be their own boss, but they often don’t want to deal with the headaches and minutiae that reality brings. How effectively can software and generative AI abstract away those complexities?

Autonomy extends to financial services, which are of course intertwined with the jobs that pay us. The best fintech products of the past 10 years gave users autonomy. Revolut let you take more control of your banking through an accessible, intuitive digital interface. Robinhood let you invest on mobile without fees. And so on.

A newer generation will extend autonomy. AfterHour blends Robinhood and Discord, offering a hub for financial education and community. The company’s Stonk Madness bracket brings retail investing to the masses and layers on a social layer non-existent on today’s trading apps. Bilt, meanwhile, lets you earn points while paying rent—and a number of upstarts are working to extend the concept to mortgage (which Bilt will also soon offer). By broadening access to financial products, fintechs shift agency away from the institution and toward the user.

A related word in both jobs and finances is flexibility. Autonomous work often means flexible work; that’s part of the draw of business-in-a-box. And we see the same in fintech. An example is the explosion of Buy Now Pay Later products, offering consumers more flexible payment options. BNPL is powered by younger consumers: consumers 35 and under comprise 53% of BNPL users (but just 35% of traditional credit card holders). And BNPL is expanding beyond big-ticket items: an Afterpay survey found that BNPL use on contact lenses soared 465% from 2022 to 2023, while use on garbage bags jumped 182%. BNPL means flexibility, a key wave hitting jobs and finances.

Shopping = Circularity

The biggest wave in commerce, in my mind, can be summed up in the word circularity. Sustainability is bleeding into commerce; consumers want to shop secondhand, and brands want to do good by their customers and by the environment. Ask any brand or retailer what’s top-of-mind for them, and two topics consistently come up: (1) resale and (2) excess inventory. The two are interrelated, and both build on circularity.

Last fall’s The Resale Revolution dug into this in more detail. A few stats from that piece:

The average American woman owns 103 pieces of clothing.

Globally, consumers acquire 80 billion new items annually—up 400% from 20 years ago.

In America, we each buy about 68 new garments a year.

Most people wear only 20% of their clothes.

Resale is growing 11x faster than broader retail.

I have one company building an end-to-end operating system for resale, which incentives for brands to share in the upside; if you’re a brand—particularly in the mid-luxury price-point—and want to be an early customer or talk to the founders, send me a note 📬

Excess inventory is intertwined with resale. Brands overproduce $500B of goods annually, and at the end of every season about 12% of clothing remains unsold. Much of this unsold product ends up in landfills like the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which covers 1.6M square kilometers in the Pacific Ocean between Hawaii and California. The garbage patch is growing exponentially, swelling 10x each decade since 1945.

The average American now generates 82 pounds (!) of textile waste each year.

I expect commerce in the 2020s and 2030s will become all about circularity; how do we use tech (bits) to efficiently recirculate products (atoms) in a scalable way? That’s the Holy Grail.

My runner-up word for shopping’s wave is “discovery.” This is the other major trend I see. Most shopping remains offline:

The share that’s online, I’d argue, is less shopping than it is buying. There’s a distinction. E-commerce tends to be search-driven and utilitarian. You go to Amazon.com and type in “paper towels.” (When a Prime member visits Amazon.com, they end up buying something 74% of the time.) That’s buying.

Less online commerce is about discovery, while offline commerce is dominated by discovery. The thing is, people like to shop. To take just grocery as a category:

Social shopping is much larger in the East than in the West. Pinduoduo is a $163B market cap business—a scale that has allowed it to plow $7B into ad spend for Temu last year, making Temu the largest advertiser on Meta last year. We see some startups pioneering discovery-driven commerce in the US: Flagship for creator commerce; Whatnot in livestream; Feed in food and grocery. “Discovery” will be another large wave this decade.

Health = Tracking

Health is in. In case you needed more proof of that, look no further than a peculiar trend among Gen Zs: flaunting your continuous glucose monitor.

Long worn by diabetics, continuous glucose monitors are now the latest fashion statement. Wearing a CGM signals, “I’m on top of my health.” You could argue the same for Oura Rings, Whoops, Fitbits, and Apple Watches.

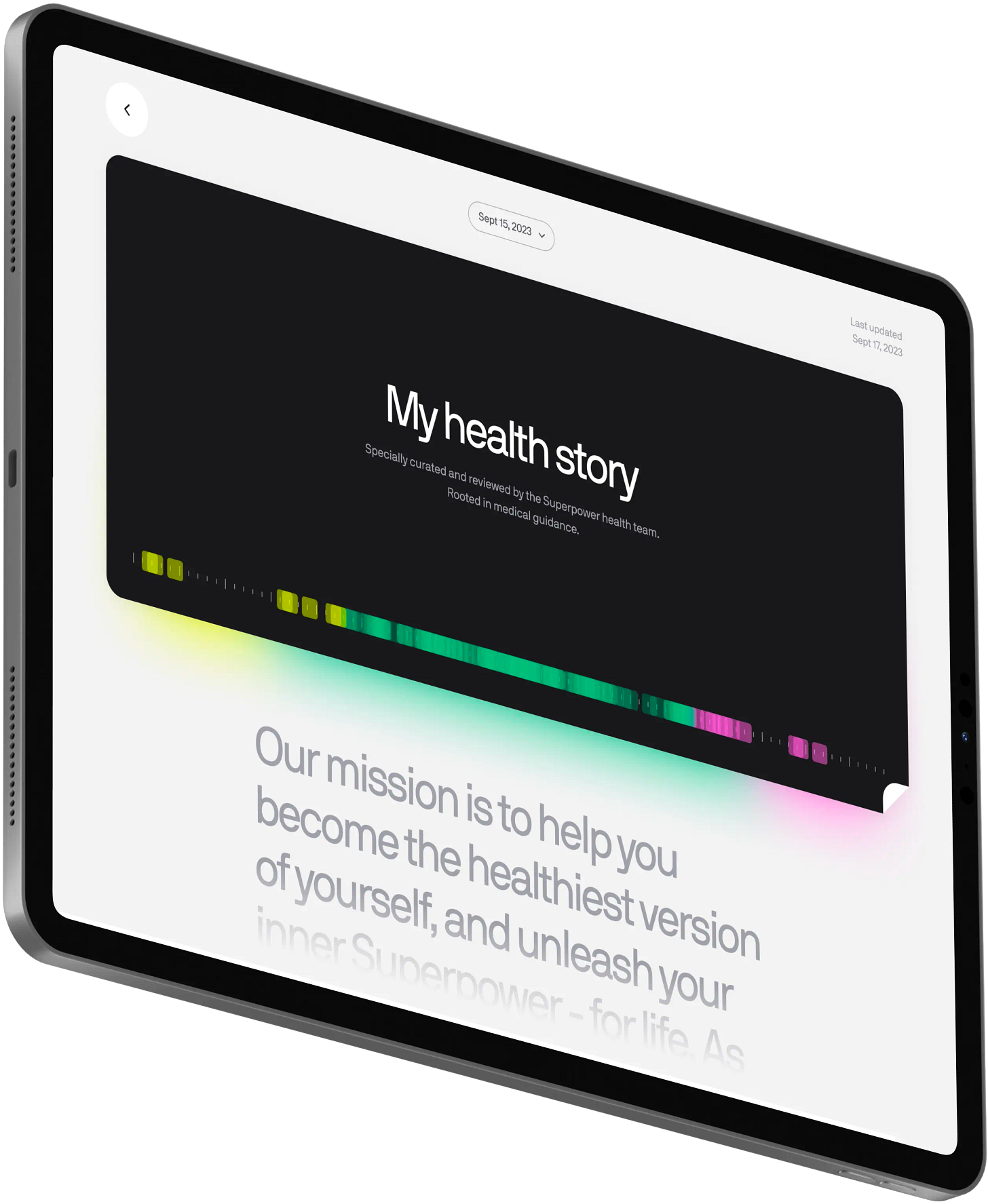

The global digital health market was worth $330B in 2022 and is expected to swell to $650B by 2025. Last month’s piece The Huberman-ization of America dug into this market in more depth, pointing out the emergence of “performance health” startups in particular. Take Superpower, for instance, which bills itself as “The world’s most advanced digital clinic for prevention, performance and longevity.”

The word that comes to mind here: “tracking.” Tracking is the wave. Health is all about data—about having a deeper understanding of your body. The next generation wants to track, track, track.

Superpower uses the word “longevity,” and that hints at another trend. What better embodies health, after all, than extending human life? Startups like Loyal are working to extend lifespan—starting with dogs. The FDA has never approved a longevity drug, but Loyal is close. Loyal’s vision is to first extend our beloved pets’ lives (Americans spend $140B on their pets each year, +11% year-over-year), before ultimately producing drugs for human longevity.

More and more young people are interested in longevity. A new survey from Dan Frommer’s New Consumer Report found that a third of Americans want to live forever (n = 3,286 in the survey):

One fascinating topic: the concept of longevity escape velocity. Longevity escape velocity is when life expectancy increases by more than a year per year.

In his conversation with Talia, Ray Kurzweil summarizes:

“Right now you go through a year and use up a year of your longevity. However, research is advancing and it’s curing various diseases. You’re actually getting back on average about four months a year. So you lose a year of longevity. You get back about four months because of scientific research. However, scientific research is also on an exponential curve. By 2029, you’ll get back a full year. So you lose a year, but you get back a year.

“Past 2029, you’ll get back more than a year. Go backwards in time. Once you can get back at least a year, you’ve reached longevity escape velocity.”

It’s a fascinating concept to contemplate. It seems far-fetched, but refer back to the chart of exponential technological advancement at the start of this piece. Far-fetched things come along quicker than we expect. And even if our bodies can’t live forever, what about our minds? This sounds dystopian, until you watch the Black Mirror episode “San Junipero.” (Check it out; that’s this week’s Digital Native homework assignment.)

Social = Latent Awareness

Gen Z is obsessed with point-and-shoot digital cameras. According to a good article in Fast Company, many old-school cameras are sold out. Kendall Jenner recently featured a Canon PowerShot ELPH 350 in an Instagram post, and now the camera is nearly impossible to find; on resale marketplaces, it goes for $399. Other point-and-shoot cameras, like the Canon G7x and the Contax G2, have been sold out and backordered for months.

For years, people have thought the next Instagram will be a more “authentic” photo-sharing platform, one with roots in the nostalgia of more analog cameras. Startups like BeReal, Dispo, Locket, Poparazzi, and Lapse have leaned into the aesthetic and ethos of old-school cameras. (Dispo is even short for “disposable camera.”) Though I love these products, I’ve never been bullish on the companies reaching massive scale. The “Instagram Killer,” in my mind, will look more like Roblox than Instagram.

Outside of 3D content and spatial computing, I see another possibility for the next generational social company: “latent awareness.” That’s the wave here—I’m cheating with two words instead of one, but even just “awareness” works. Awareness builds on the wave of tracking in health. Both have the same root: we’re all hungry for information.

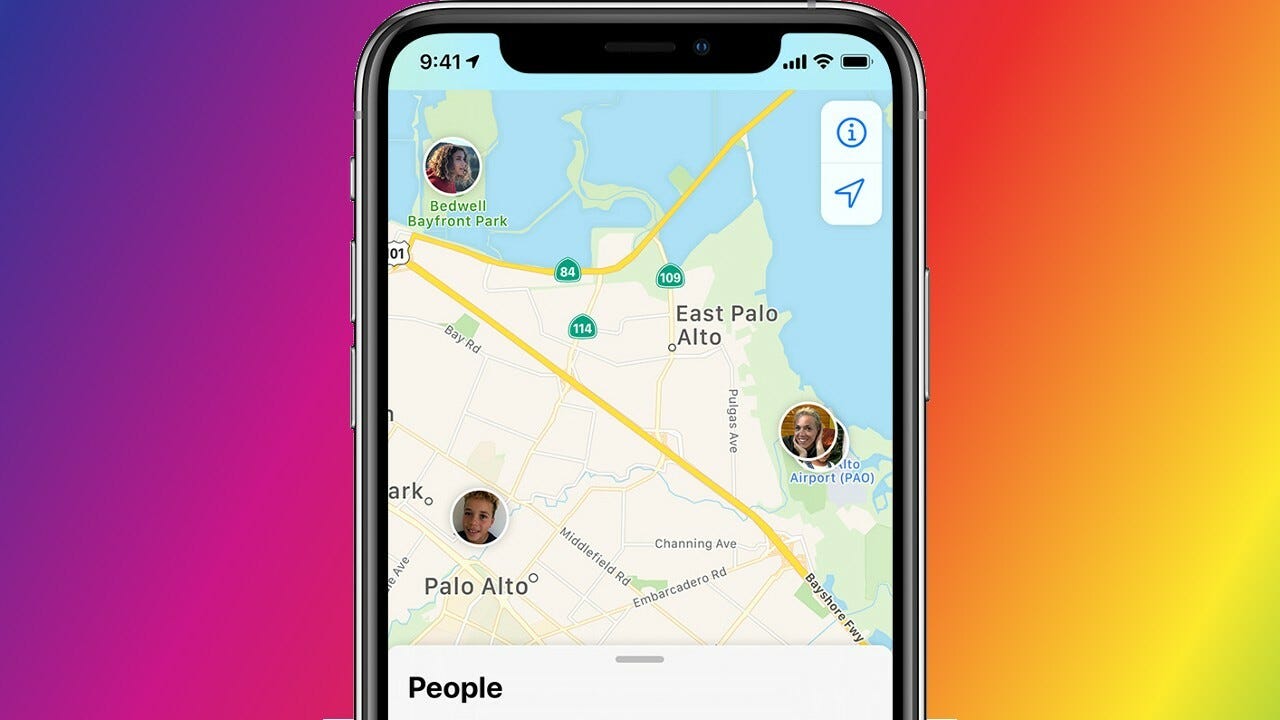

The most popular social app of the moment has quietly become Find My Friends. People like to know where their friends are. Is Emily at work? Oh cool, Mason’s chilling at home today. What’s Rachel doing over in Brooklyn? One girl on TikTok admits to making sure all her friends are safely at home every night—she calls it, “Checking up on my Sims.”

Find My Friends is about latent awareness—in its case, awareness of location. What if our phones could auto-populate a social feed with a lot of other data on us? Not just location, but everything else. What is Rex reading, writing, eating, watching? Some of this is scary to think about, sure, but privacy doesn’t matter much to young people. I expect we’ll see some real innovation in social that builds around awareness.

Final Thoughts

We live at a fun (and scary) moment. Things have never been changing faster. Technology continues at a breakneck pace—and an exponential one, meaning that things will get crazier and crazier every year. Moore’s Law told us that things would double every couple of years. In the last decade, though, AI has advanced by about a million times—many, many times the pace set by Moore’s Law.

And on the societal and cultural front, global connectedness means that behavioral shifts also travel at warp speed. Waves, both technological and behavioral, are ripping through the world.

The themes above are just a few examples. Each category has many waves, big and small. But I expect those mentioned here are some of the most prominent. In the early-stage venture world, there’s only so much you can do to pontificate on founder and product—the two are right in front of you, often more objective than subjective. The wave is harder to forecast, and so we spend a lot of our time thinking and questioning and wondering and predicting. Kurzweil is famous for being a “futurist” (name a cooler title, I’ll wait) but that’s really what we’re all trying to be—we have no idea what the future holds, so do our best to predict which waves will carry us into it.

Sources & Additional Reading

Check out BVP’s Talia Goldberg in conversation with Ray Kurzweil

Shoutout to Casey Lewis at After School for always showing me what to read up on around Gen Z

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: