The Evolution of the Creator

Cloning Myself and Exploring the Companies Powering Creator 3.0

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 65,000 weekly readers by subscribing here:

Hey Everyone 👋 ,

With the election monopolizing our attention last week, I decided not to publish a piece. We’re back this week with a refresh of a long-held thesis on the creator economy, exploring the evolving definition of “creator” and theorizing which companies might power the next generation of parasocial relationships.

Let’s dive in 👇

The Evolution of the Creator

Last week, I watched Netflix’s new documentary on Martha Stewart. My takeaway: Martha Stewart was, in many ways, the first influencer.

Stewart got her start in the 1980s when she published her first cookbook, Entertaining, which quickly became a bestseller. She parlayed that success into more books, and then into the magazine Martha Stewart Living, launched in 1990 with TIME. By 1995, the magazine had a circulation of 1.5M copies. Around the same time, Stewart launched her syndicated TV show of the same name, reaching 90M American homes.

On the back of her growing empire, Stewart created the company Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia (MSO), which IPO’d on the New York Stock Exchange in 1999 with a market cap around $2B. By 2001, the company’s revenue had reached $300M and Stewart was worth $1B.

(Stewart’s story is even more remarkable given its origins: Stewart learned to garden because her family was low income and relied on the food grown in their garden. She was America’s first self-made female billionaire.)

Of course, Stewart’s brand came crashing down to earth after her insider trading scandal and jail time. But for decades, she embodied the definition of “influencer”: an aspirational personality—a one-woman brand—commanding a one-to-many omni-channel relationship with millions, shaping American culture.

Stewart paved the way for the Kim Ks and Emma Chamberlains of the 21st century.

Watching Martha, I found myself thinking about how the meaning of “influencer” has evolved over the years, and how the companies that underpin the influencer economy will change in the coming decade. This has been a frequent topic on Digital Native. One of our first-ever pieces covered the phenomenon of everyone becoming an influencer. From that piece:

Just as silent film stars like Norma Desmond were replaced by movie stars like Grace Kelly and Bette Davis a century ago, today’s movie stars (your Angelina Jolies and Jennifer Lawrences) are being replaced by internet stars. The internet obfuscates the gatekeepers of fame; anyone can be influential.

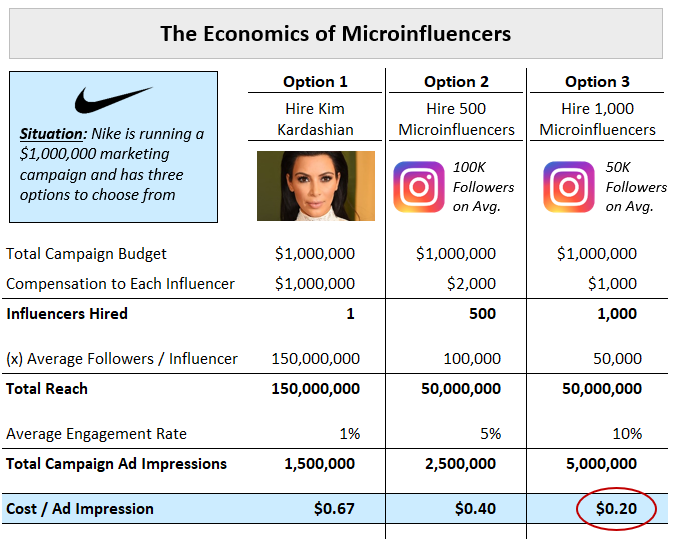

That piece went on to look at the birth of the “microinfluencer” and how influencer marketing was rising as an acquisition channel:

A general truth on internet platforms is that smaller audience sizes have higher engagement rates. In other words, someone with 1,000,000 followers might average 1% engagement (likes + comments) on their posts. Someone with 100,000 followers, meanwhile, might average 5% engagement. This means that “microinfluencers”—people with ~10K to ~100K followers—have better economics for brands.

Future pieces, like 2022’s Influencer Marketing 2.0, dove into the influencer stack in more detail. In those pieces, I used the word “influencer” because I focused on the advertising side of things. To me, “influencer” works best in this context—a person is influencing a purchase decision. In this piece, though, I’ll expand to the broader term “creator,” which I prefer these days. I like how Patreon’s Jack Conte frames the difference: “influencer” extracts the one thing advertisers care about—influence—and overlooks creativity and self-expression. As he puts it: “I don’t wake up in the morning to influence; I wake up in the morning to create.”

In this piece, we’ll outline Creator 3.0—what the next generation of the creator economy looks like.

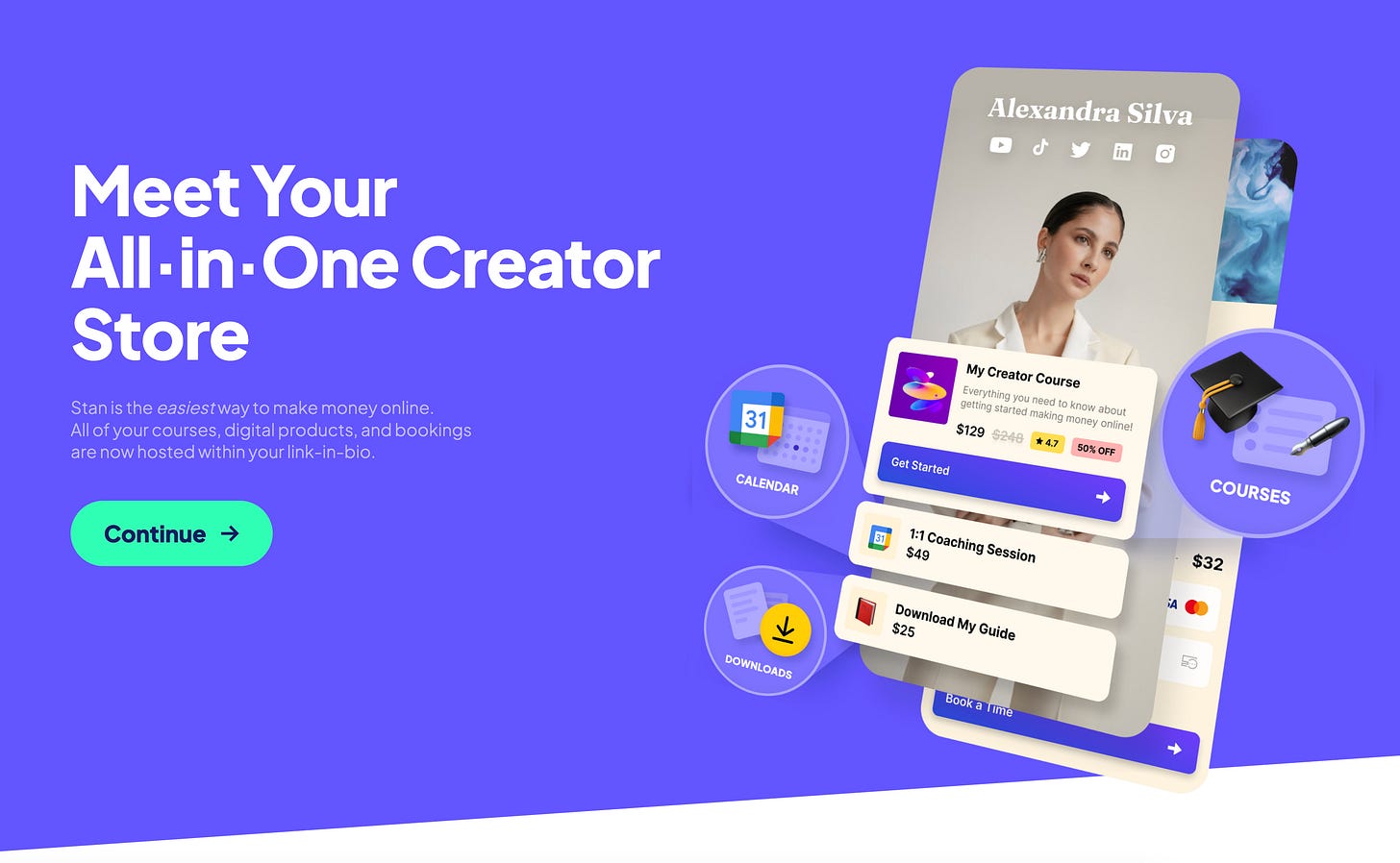

We’ve come a long way from #sponsored hashtags; many large technology companies have been built on the back of the creator phenomena, though venture capitalists typically take a too-narrow view of the creator economy. Great creator companies often fit neatly into other sectors, but have a creator angle: YouTube is a content platform; Twitch is livestreaming; Stan is a commerce company. Each, of course, builds on the phenomenon of parasocial online relationships.

The majority of creator companies aren’t venture-scale businesses: we only need so many link-in-bio or creator CRM companies, and the path to $1B+ revenue is questionable. The biggest opportunities, instead, lie in how creator intersects with other spaces: commerce, gaming, social, prosumer SaaS.

We also don’t need many creator brands: consumers have been inundated with far too many, and you can see a backlash brewing. (Exhibit A: the lukewarm reaction to Brad Pitt’s new skincare line.) Just because someone has a large following—and thus built-in distribution—doesn’t mean they should launch a lifestyle brand; there needs to be a net-new product insight. We explored this truth in last year’s The Retail Revolution, looking at how Beyoncé’s Ivy Park has floundered (she should’ve done luxury!) while more innovative businesses with better “creator-market fit” have soared.

The creator/celebrity brands that endure do three things right: 1) They’re authentic to the creator, 2) They have a genuinely unique insight, and 3) They move beyond the figurehead. The two most successful examples, in my mind, are Rihanna’s Fenty and Kim Kardashian’s SKIMS. Their unique insights:

Fenty: Make-up should come in more shades for people of color.

SKIMS: Shapewear is outerwear.

Both are raking in hundreds of millions, if not billions in revenue. They injected new energy into stale categories.

Anyway. The point is, “creator” is a lot more than influencer deals and celeb brands. There are a few $10B+ companies waiting to be built for the next generation of creators.

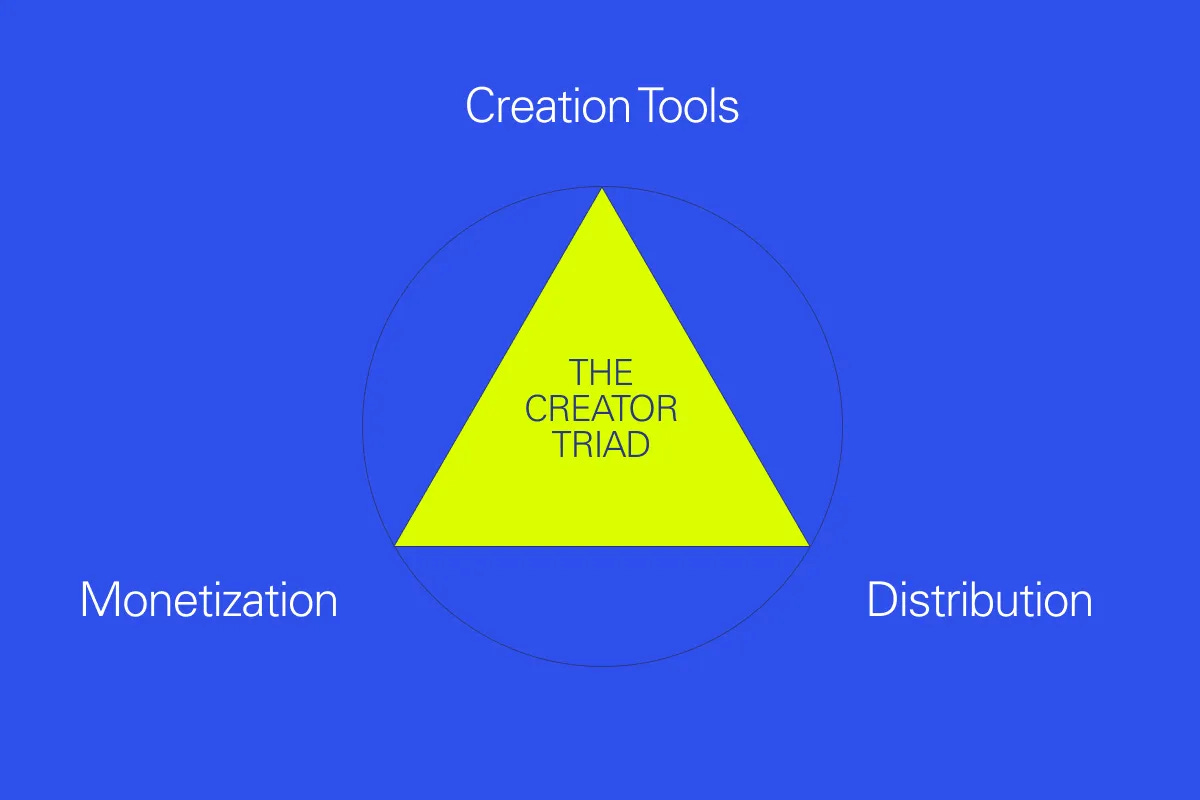

I’ll frame this piece around the Creator Triad, one of my older frameworks. In my view, it still effectively captures the three components of the creator ecosystem:

The first piece of the puzzle is democratizing creation itself. The best tools broaden the scope of who can be a creator: think Figma and Canva for design; Descript and Splice for audio; Unity and Unreal Engine for gaming. Elegant, design-first tools unlock new levels of self-expression.

The second piece is distribution. Traditionally, gatekeepers dictated who had influence: record labels, newspaper editors, studio executives. Online, though, anyone can build a community. You can share videos to YouTube, writing to Substack, music to Soundcloud.

The final piece of the triad is monetization. How do creators earn a living? We see platforms here emerge for everything from physical products (Etsy), to digital products (Whop), to game experiences (Roblox), to adult content (OnlyFans).

In short:

First, you have to make stuff.

Then you have to get that stuff in front of people.

Then you have to get paid for it.

Let’s dive in.

Creation Tools

The obvious innovation in creation tools: generative AI.

One could easily argue that gen AI will most impact this piece of the creator triad. Why? Because gen AI is a production revolution.

In Weapons of Mass Production, we wrote:

The internet was a distribution revolution. At its simplest, the internet is all about networks. Rails for information, data, content, commerce, and communication. AI, meanwhile, is a production revolution. Generative AI makes it really, really easy to make stuff. It blows open the floodgates of production.

What the Industrial Revolution was to physical production, the AI Revolution will be to digital production.

That piece went on to show how easy it’s become to make cool stuff with AI. I even got to turn myself into a Family Guy character using Midjourney!

Soon, I should be able to create my own entire Family Guy episode in a few clicks. In the midst of OpenAI’s Strawberry demo, massive fundraise, and purchase of the chat.com domain name for $15M (!), it would be easy to forget about Sora. But Sora is rumored to be approaching wide release, and it’s as stunning as ever. A sample prompt:

Several giant wooly mammoths approach treading through a snowy meadow, their long wooly fur lightly blows in the wind as they walk, snow covered trees and dramatic snow capped mountains in the distance, mid afternoon light with wispy clouds and a sun high in the distance creates a warm glow, the low camera view is stunning capturing the large furry mammal with beautiful photography, depth of field.

It’s gorgeous and cinematic, nearly movie quality. No need to hire a bunch of wooly mammoths to get the shot.

We’re around the corner from some pretty incredible production tools. It’s already stunning what you can do. In July’s Keeping Up with the Gen Zs, we created the song Echoes of Summer with a simple text prompt, using Suno.

Or take what Decart has built. Oasis is a video model trained on millions of gameplay hours. Users can explore and shape environments in real-time. Check it out.

Creative tooling is an underrated category.

Canva continues to fly under the radar, but the business actually generates more revenue than Figma, Miro, and Webflow combined. Canva does $2.3B per year in top-line, has 185M monthly users across 190 countries, and has been profitable every year for over seven years (!). CapCut is overlooked because it’s owned by Bytedance, but it was the 2nd-most-downloaded free iOS app in the world last year—above Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok, and behind only Temu.

With AI, the difficulty of making good stuff goes down an order of magnitude. This crowds in a new generation of creators, who are able to spin up gorgeous, high-fidelity works with a simple prompt.

Distribution

I’d argue we haven’t seen much recent innovation in distribution, though it’s where the biggest creator companies have traditionally emerged.

The rails here are the big platforms: YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, Spotify. When a company cracks a new form of distribution, it can get very large. YouTube was the belle of the ball for Alphabet’s Q3 earnings two weeks back, posting strong growth and raking in $50B+ over the past four quarters. In 2024, the analyst Michael Nathanson estimated YouTube would be worth $400B as a standalone company. Instagram would probably be worth around the same, if it weren’t part of Meta. (Google’s $1.65B acquisition of YouTube and Facebook’s $1B acquisition of Instagram will go down as two of the best acquisitions of all time.)

We haven’t seen a new winner emerge in distribution in a long time. We have some solid companies here, like Linktree for link-in-bio or Grin for scaling influencer marketing—but where’s the $10B+ company?

Big companies typically emerge from category creation. And AI seems poised to create a category or two.

Take digital clones.

Delphi is a company that lets you clone yourself. The tagline on the website: “Build the digital version of you to scale your expertise and availability, infinitely.” I worked with Delphi’s founder, Dara, to make a Rex clone 🙋🏼♂️ This basically means ingesting all my past writing, podcasts, and interviews to build a smart AI that can…well, talk like me.

You can play with my clone here:

It’s actually pretty fun. I already talk to myself all the time, but now I get to do it with an AI.

Delphi starts with suggested questions. This is smart product design; talking to a clone is a new behavior, so we need some nudges in the right direction:

If I click one of the suggested questions, the Rex clone spits back a pretty coherent answer.

That’s basically how I would’ve answered that question.

If I click another, same thing:

This is a cool way to scale a scarce resource (time) for any creator. Intro is one of many companies that lets you book time with an expert. But just look at these prices:

Isn’t it a lot more economical to talk to a clone?

I expect clones will be one example of category creation that emerges from AI, reinventing how creators connect with their communities.

Monetization

Monetization is probably the least-saturated category of the three, with the most whitespace. It’s traditionally been tough for creators to make money. Only a handful of top creators can truly earn a living through their work.

That’s beginning to change, and we’re seeing good innovation here. I’ve written in the past about one of our Daybreak companies, Flagship, and how it’s powering a new generation of creator small businesses—online merchants who curate products and influence purchases within their communities. Affiliate has been messy and broken and opaque for a long time; Flagship is reinventing affiliate with a cleaner business model and a full-stack commerce offering.

Or take the cloning example above. Creators will be able to monetize their likeness in new and creative ways.

Last year, the 23-year-old influencer Caryn Marjorie made headlines for training a voice chatbot on thousands of hours of her own videos, then selling access to that chatbot for $1 a minute. Within a week, she’d made $71,610. That money actually came from only ~1,000 beta testers, meaning that the average user spent over an hour chatting with CarynAI at $1 / minute. Clones are a good way to unlock willingness-to-pay from super-fans.

And with AI exploding the gates of production, it will become more important to track IP ownership and usage. Atomic units of culture can be composable, assembled into new stories. Blockchain promised to help us track monetization for IP rights holders, and it still has promise—but we’ll need some clever rails to monitor and capture value for creative output.

Final Thoughts

The biggest winners in the creator space often combine all three aspects of the triad. Roblox, for instance, offers Roblox Studio for developers to build experiences, while facilitating the discovery of experiences and allowing for monetization through its own in-world currency, Robux. Roblox is an amalgam of a bunch of interesting companies—it’s YouTube meets Lego meets Facebook meets Epic Games.

Or take TikTok. TikTok also allows for easy video creation (particularly paired with CapCut), algorithmic discovery, and monetization. Check, check, check ✅ ✅ ✅

I expect we’ll have a few large venture outcomes that also touch on all three—creation, distribution, and monetization. I’m particularly interested in a next-gen Roblox (it boggles my mind that you have to know Luau to build in Roblox) that uses AI to crowd in a longer tail of creators, and I’m also spending a lot of time in the fan-fiction world, looking at how AI allows fans to spin up their own stories and build with each other’s IP Lego blocks.

The creator phenomenon—the concept of people having parasocial relationships online, making stuff and sharing it and earning income—isn’t going anywhere. It’s one of the biggest phenomena of the online age, and it will underpin another generation of large technology companies.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: