The "Why Now" for Healthcare

Regulatory Capture, the Lack of Exits, and a Potential Turning Point

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 65,000 weekly readers by subscribing here:

The "Why Now" for Healthcare

If you go to buy a COVID test at Walgreens, you’ll see seven tests, each available for $23.99. Now, if you go to buy a COVID test at Boots in London, which is owned by Walgreens, you’ll shell out $1.50 per test. That’s more than a 10x price differential. What gives?

In short, regulatory capture.

In regulatory capture, special interests are prioritized over the general interests of the public. This leads to a net loss for society. (For those who took Econ, remember the term “deadweight loss?”)

The price of COVID tests is one example. The backstory here is that during the height of COVID, the Biden administration ordered the production of antigen tests. But ultimately, the government only approved three vendors: Abbott, Ellume, and Quidel. Why only three? That doesn’t sound like an efficient marketplace to me. (By the way, the lateral flow assay that’s in every test—the popsicle stick-like thing—is commoditized and quite cheap.) In short, there were only three vendors because of special interests. The guy who made the call—Timothy Stenzel, Director at the FDA—had an interesting job history: five years at Quidel, four years at Abbott. Hmm. 🤔

One of my favorite talks in recent years is a talk delivered by Bill Gurley called “2,851 Miles.” The title of the talk references the distance between Washington D.C. and Silicon Valley, capturing Gurley’s main argument: the reason that Silicon Valley has been so successful is that it’s so damn far from D.C.!

This is because innovation is often at odds with regulation. One of the key takeaways from Gurley’s talk is a sentence he makes the audience repeat back to him. Say it with me now: “Regulation is the friend of the incumbent.”

Regulation is the friend of the incumbent. This is why we see Coinbase’s Brian Armstrong, Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg, and OpenAI’s Sam Altman all push for regulation in recent years—notably, after they’ve each achieved market-leading positions.

Regulation is especially present in U.S. healthcare. To finish the antigen test example: in Germany, the government evaluated 100 potential tests; 96 were approved. In Germany today, you can buy five tests for $3.75—about 75 cents apiece (!). Lack of competition = a net loss for society (in America’s case, in the form of artificially-high prices driving artificially-constrained demand, and thus lower testing).

To take another healthcare example, consider Epic, the largest player in electronic health records (EHR) software. In 2009, Obama put Epic’s CEO, Judith Faulkner, on his Health IT Council—the only corporate representative. Unsurprisingly, Faulkner had been a major Obama donor.

When Obama passed the American Recovery Act that year, tucked within the act was the creation of an agency called the ONC: the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. The ONC came up with a bright idea: the government would give doctors $44,000 each if they bought medical records software. Overall, the government would spend $38B to encourage the digitization of healthcare. Modernizing our health system sounds like a good idea, right? So far, so good.

In a second phase, the government would encourage doctors to use the software with another $17,000. This part was called “Meaningful Use.” This is also smart: gotta incentivize usage too. Again—so far, so good.

Then things get murky: the ONC came up with thresholds you’d need to comply with to get the government’s money. And—shocker—the thresholds looked almost identical to Epic’s feature set. (Remember: Faulkner was on the council deciding the thresholds.) The government issued three heavy fines—$144M, $57M, and $145M—against Epic’s competitors for not complying. For Judith Faulkner, this was a masterclass in wielding government influence for corporate interests.

Gurley’s talk is worth watching in its entirety—it’s chock-full of great examples of regulatory capture—but this image really sums it up:

Disruptive innovation is the arrow moving exponentially up-and-to-the-right; regulatory capture is the brick wall stiff-arming innovation along the way.

The below chart is a favorite in Digital Native. It depicts the price change of goods and services over the last quarter-century. The things below the x-axis tend to not have much regulatory capture: TVs and software don’t face much government meddling, and we see precipitous price drops as a result. Everything above the line, though—healthcare, education, housing—has a lot of regulatory capture.

It’s the sectors above the x-axis where capitalism is broken in its current state, and where there remains massive opportunity for disruption.

I’ve been spending a lot of time in healthcare lately. This is partly because there’s been a dramatic increase in the number of high-quality founders I see building in the space. When in doubt, a good rule of thumb in startups is: follow the talent. And this is partly, relatedly, because there are a few good “why nows” for healthcare—more on those in a moment.

Traditionally, healthcare hasn’t been a great market for venture capital. Yes, healthcare is America’s largest sector—about $5 trillion, ~20% of GDP, and our biggest employer (~20M Americans strong). But exits have been modest at best. We have a few acquisitions and IPOs, sure—Livongo, One Medical, and so on. But where are the $50B+ companies? UnitedHealth Group is a $500B+ market cap business! Surely some startups should’ve been able to get to double-digit billions on the backs of the seismic shifts we saw in internet and cloud?

Regulatory capture has been part of healthcare’s dilemma, and there’s reason to think that things are finally changing. This week’s piece dives into what’s compelling right now in healthcare. We’ll start by looking at the “why now” and then we’ll dig into B2C and B2B opportunities.

The “Why Now” for Healthcare

B2C Innovation

B2B Innovation

The “Why Now” for Healthcare

I’ve written in the past about how Daybreak was initially called “Tectonic.” This is because I’m interested in the tectonic shifts that shape everyday life, and the biggest startups are often built along colliding shifts in technology and behavior. Three examples from July’s Keeping Up With the Gen Zs:

Eventually, we abandoned “Tectonic” in favor of a less austere, more optimistic name—but I still spend my time thinking through major shifts.

Healthcare finds itself at the intersection of a lot of shifts:

Technological Shift

This one is two-fold. On the one hand, we have the ongoing shift toward telehealth: more people are getting care online. On the other hand, we have the more recent shift in AI. Healthcare tends to run on lots and lots of language—and it turns out large language models are pretty good at parsing language.

Demographic Shift

America is getting older. Every day, 10,000 more Americans turn 65, and there are already more Baby Boomers in the U.S. than there are people in the U.K., Israel, and Switzerland combined. We’re on track for more than one in five Americans to be a senior citizen by 2040. (Half the country is already over 50.) By the way, this is also a global phenomenon: people 65 and older will soon outnumber children under 5 for the first time in history.

Cultural Shift

McKinsey sizes the wellness industry at $500B in the U.S. and $1.8T globally. About 80% of American consumers say wellness is a top priority in their lives. Wellness is a squishy category, encompassing everything from Botox to skincare to melatonin to weighted blankets. That’s a wide range. But the crux is: people care more and more about taking care of themselves, and they’re willing to spend on that self-care.

This is especially true for younger consumers:

Another cultural shift: young people want mission-driven, impactful work. This is one reason that we see founders moving into healthcare, an inherently impactful space. And it’s a reason that these founders have an easier time attracting top-notch engineering and product talent; young people want to feel fulfilled in their careers.

Regulatory Shift

After COVID, telehealth restrictions have loosened. The pandemic was also a wake-up call for healthcare more broadly, shocking a lethargic and analog industry into modernizing. Regulation continues to be a buzzsaw in some segments of healthcare, but we’re seeing many providers and payers begin to embrace startup innovation.

Breaking Point

This one isn’t a real shift, but something of a bonus. I call it “Breaking Point” and it’s the result of two colliding forces: (1) ballooning healthcare costs, (2) declining healthcare outcomes. How can America spend more on healthcare than any other developed nation—$13,000 per person annually, double countries like the United Kingdom ($5,500) and Canada ($6,300)—yet have worse health outcomes?

Spring’s The Telehealth Tipping Point offered a “health check-up” for America, and I’ll share some of the key charts here. In fact, we can do a mini-version of the 10 Charts series by looking at why America is overdue for a reckoning in health. Here are 10 charts that visualize what’s going on in American healthcare, showcasing our Breaking Point:

America’s Health in 10 Charts

Healthcare costs are going up relative to GDP.

This is alongside rising per capita out-of-pocket expenditures:

Yet our outlier per capita spending actually gets us worse life expectancy than our peer developed nations:

And despite how much we pay, it’s not exactly easy to see a doctor:

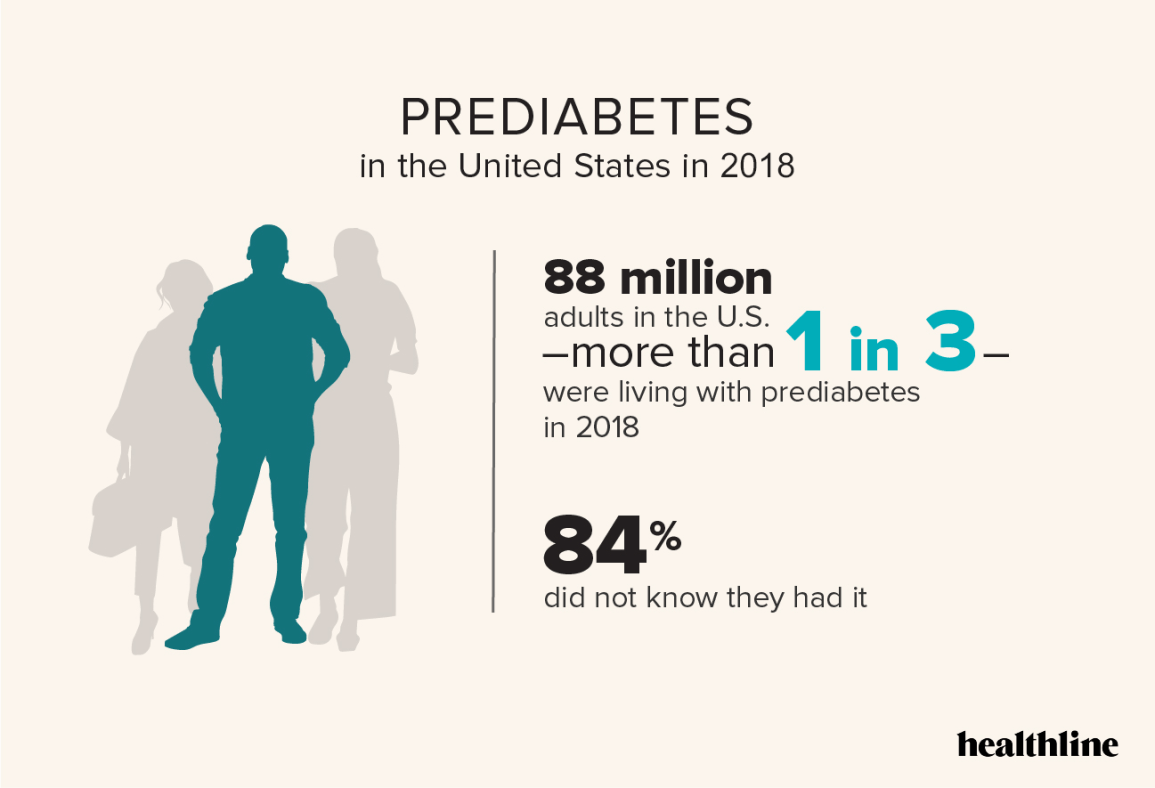

Three in five Americans have a chronic condition; two in five Americans have 2+ chronic conditions. About one in five Americans have diabetes—38 million people—and 20% of those people don’t even know it. One in three are living with prediabetes, and 84% don’t know it.

Part of the reason: we’re an obese nation. In 1990, zero states had obesity rates above 20%. In 2018, zero states had obesity rates below 20%. Check out this graphic:

Here’s how we compare to Europe:

Obesity is arguably the crisis of our time. Its competition, perhaps, is our mental health crisis. Over 60% of young adults report “serious loneliness” and over 20M American adults have experienced a major depressive episode. Rates of depression have been steadily ticking up:

And, of course, healthcare is unequal:

To cap it off, the people who attend to our declining health are burnt out:

Okay, so America’s physical gets a lousy grade. What do we do about it? Thankfully, we’re seeing a lot of innovation.

B2C Innovation

On the B2C side, we’ve of course seen consumer hardware take off. A peculiar trend among Gen Zs: flaunting your continuous glucose monitor, long worn by diabetics but now becoming the latest fashion statement. Wearing a CGM signals, “I care about my health.” You could argue the same for Oura Rings, Whoops, Fitbits, and Apple Watches. And if I have to endure one more dinner party where we spend 30 minutes talking about Eight Sleep mattresses… 😑

When it comes to marketplaces and software, though, a lot of the innovation in consumer(ish) healthcare has happened through the MSO model.

MSO stands for Management Services Organizations, and it effectively means: we’ll help you handle all of the administrative, non-medical work. MSOs are most prevalent in behavioral health. Headway and Grow are both MSOs that help therapists abstract away the complexities of being a therapist: billing, filing claims, collecting payments, credentialing, patient interactions, and so on.

A subset of the MSO model is business-in-a-box, which we covered earlier this year in Business-in-a-Box 2.0. I’d argue that business-in-a-box layers on one key feature: matching between provider and patient, helping the provider “build their book.”

I expect we’ll see the MSO model expand widely across healthcare; it’s a proven playbook that allows startups to grow rapidly.

I’m also interested in companies that expand their market by making a service (1) easier to access, and (2) more affordable, typically through insurance coverage. An example here would be the up-and-coming dietitian companies: Nourish, Fay, and Berry Street have each rapidly scaled to tens of millions in top-line by letting anyone spin up a consultation with a dietitian and get it covered by insurance. This is an example of payers leaning in to startup innovation—eventually, though, companies will need to prove outcomes. This is especially true in behavioral health, which has gotten very crowded. Payers are going to want evidence-based clinical outcomes.

Another interesting startup model focuses on high-LTV customers—patients with deep (and expensive) needs from the healthcare system. Examples here would be Charlie Health (high-acuity teen mental health) and Equip Health (eating disorder treatment), both of which have scaled to impressive scale. When you have such high per-patient spend, you don’t need many patients to hit $100M in ARR.

And, of course, AI is coming. Last month’s piece AI’s Privilege Expansion tackled how AI expands access to expensive, hard-to-get services. Access to healthcare professionals is a prime example. There are a lot of healthcare needs that don’t require a long wait time and an in-office visit. We’ve seen some startups begin to innovate here: Summer Health, for instance, lets parents text a pediatrician and get a response within 15 minutes.

AI is the natural next-step. Doctors and nurses have limits on their time; many questions can be answered by a trained model. A fun fact about me is that I’m someone who always has some bizarre skin thing going on (TMI?). If my dad’s med school roommate wasn’t a dermatologist, I’d be in trouble. But not everyone has a derm on speed dial. Again, privilege expansion; this is where AI comes in.

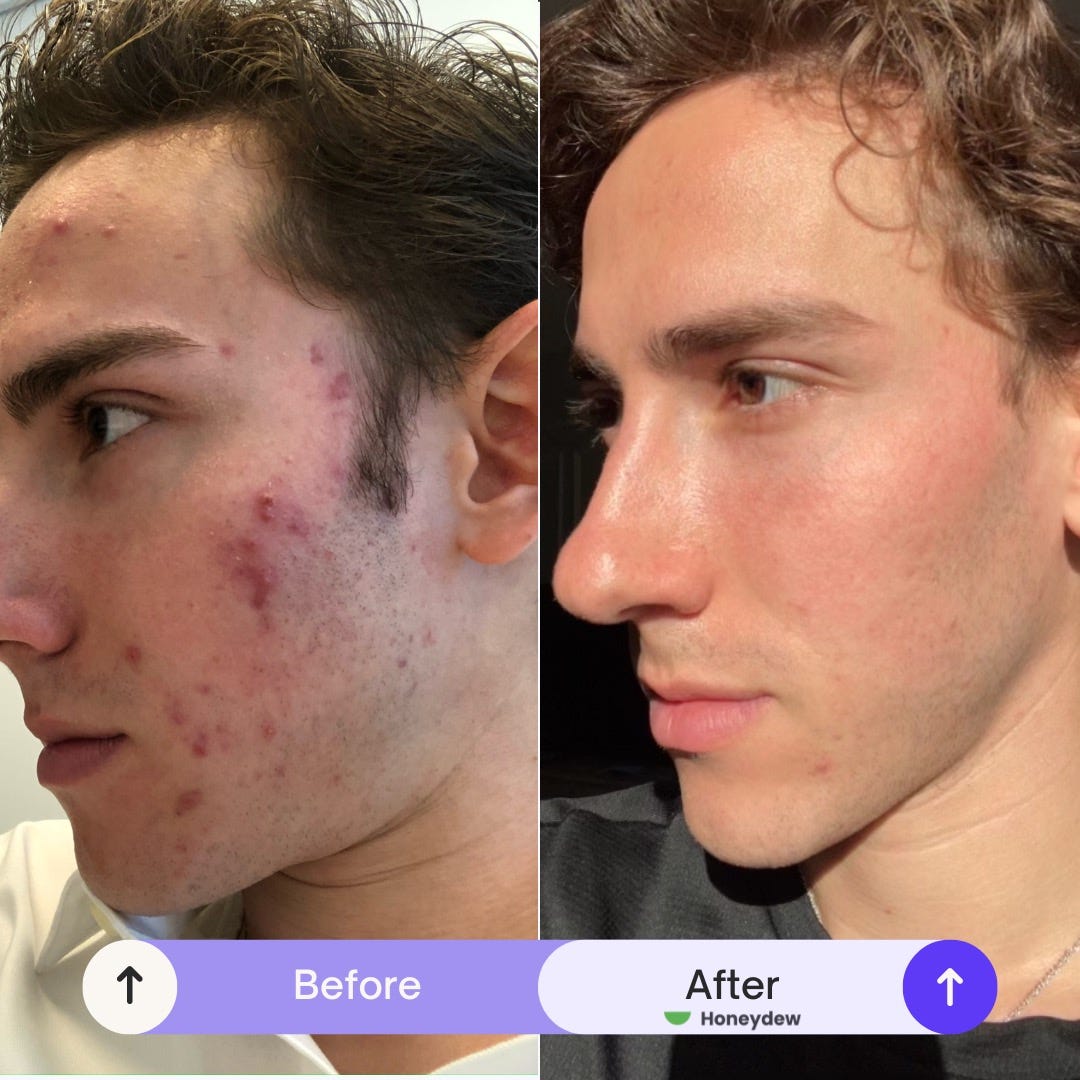

I’ve written in the past about Honeydew, a Daybreak company broadening access to dermatological care via telehealth. AI is a natural extension: I can snap a pic, text in my symptoms, and the AI can recommend the right topical steroid to treat my issue.

I expect we’ll see AI verticalization by specialty. Models can be trained and fine-tuned on specific sets of data—including your own health data. In healthcare, specialization and expertise (which are of course closely related) rule supreme, and technology products will be no different.

B2B Innovation

As mentioned above, healthcare runs on medical records—which are just lots and lots of language. And LLMs are very good at digesting that language (it’s right there in the name!), drawing insights, and taking action.

What’s more, because medical records are private, horizontal chatbots can’t train on them—this gives vertical healthcare players an edge, and it’s one reason many leading AI healthcare startups have used medical scribes as their wedge (Ambience, Deepscribe, Freed) into becoming the operating system for health systems.

Healthcare also involves a lot of grunt work—work that can abstracted away by agents. On the B2B side, we should see agents handle a lot of rote, monotonous tasks. Companies can accomplish this with both text and voice. I’ve met a few companies that are using voice agents to tackle insurance claims. As someone who spent an hour on the phone with Cigna last week—why not have a smart voice agent handle the back-and-forth regarding a claim?

When it comes to B2B, I’m particularly interested in Medicaid and Medicare.

Medicaid covers about 20% of Americans—around 75M people. About four in 10 births in the U.S. are covered by Medicaid.

Medicaid also has its “why now” moment: enrollment inflected during the pandemic and has continued on an upward trajectory:

Yet as the number of members in Medicaid have soared, the number of Medicaid providers has declined. Medicaid is, to put it frankly, a pain in the ass. Startups have been discouraged to enter the space because of low reimbursement rates—but with about 3 in 4 Medicaid beneficiaries now enrolled in managed care plans, plans have incentives to boost quality and cut costs. This makes Medicaid a compelling area to build in, powered by strong tailwinds and a technology shift—AI can automate many of the most cumbersome Medicaid workflows, lessening the administrative burden.

As for Medicare, think back to the aforementioned demographic shift: America is getting older. There are 67M Americans who are Medicare beneficiaries, and Medicare spending is expected to grow at a 7.4% CAGR through 2032.

There also political tailwinds. Vice President Harris recently unveiled a plan called “Medicare at Home,” in which she proposed expanding Medicare to cover in-home senior care. The goal here is to help compensate adults who care for aging parents. From Harris’s plan:

“Medicare will cover home care for the first time ever for all of our nation's seniors and those with disabilities on Medicare who need it, in addition to vision and hearing benefits to help seniors live independently for longer.”

Final Thoughts

If the U.S. healthcare system were its own standalone economy, it would be the 4th-largest in the world. This is a big market, and it’s ballooning: in 2025, employers will spend 50% more on employee healthcare than they did in 2017.

Healthcare will always be intertwined with regulation; there will always be regulatory capture. But we’re seeing payers, providers, employers, and consumers embrace sector innovation with new fervor—particularly as health outcomes decline and prices rise. The pandemic shocked us into action, and telehealth and AI provide a compelling “why now” to start exploring better solutions.

Of course, this is a sector that always hinges on government. The U.S. election next week will send shockwaves through healthcare, regardless of the outcome. If Trump wins, will he try to repeal Obamacare again? There’s no John McCain to save it this time. Will women’s healthcare be further restricted? If Harris wins, in what ways will she expand the ACA and bolster Medicaid / Medicare, while protecting women’s healthcare rights?

Next week will be a key one to watch—we can add another shift to the aforementioned five. But no matter what happens, healthcare is in for a reckoning. It’s about time.

Sources & Additional Reading

Check out Bill Gurley’s 2,851 Miles talk here

If you’re interested in Medicaid, Pear has a good Medicaid primer

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: