Daybreak: The One-Year Update

A Progress Report on Building a Venture Capital Franchise

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 60,000 weekly readers by subscribing here:

Daybreak: The One-Year Update

A year ago this week, I announced Daybreak in a piece titled Daybreak: Venture Capital for the Next Generation. That piece laid out the thesis for Daybreak and explored the “why now” for a new early-stage, artisanal venture capital franchise.

We’re now 12 months into this journey, so I’ll use this week as a status update—a way to check in on how things are going and offer a broader look at the venture landscape.

Why write a one-year update?

I’m a big believer in building in public. Building in public encourages intellectual honesty. It acts as a forcing function to stay disciplined on nailing our thesis and to remain focused on the long-term.

When launching Daybreak a year ago, we registered the fund under Rule 506(c). Typically, venture firms aren’t allowed to announce a fund until the fund is closed; this is because of rules that prevent investor solicitation. But Rule 506(c) allowed us to talk publicly about Daybreak alongside the fundraise—the downside has been a bit more paperwork, but that downside is outweighed by the upside: delivering more transparency to an industry that’s often a black box.

So what has Year 1 of Daybreak encompassed?

Fundraising

Certainly, fundraising. To invest capital you need to, well, have capital.

We now have four anchor investors—two Family Offices and two Fund of Funds—and a long tail of great LPs. We also opened a portion of the fund to members of the Digital Native community, which I’m proud of. A significant portion of the past 12 months has been spent building the Daybreak LP base.

The fundraising journey has given me empathy for the founder experience; most GPs at major firms have never had to raise the capital they invest. Fundraising means time away from finding great founders and working with them—but that’s the price to pay for autonomy, and to do this job the way I believe it should be done.

In my Q2 update to LPs, I wrote, “One thing that keeps me up at night: time spent investing vs. time spent fundraising.” One of my anchor investors emailed back, “This will keep you up the rest of your career.” The tension between capital input (LPs) and capital output (founders) is a delicate balance to strike, but should become easier over time.

Today is arguably the most difficult time to raise a fund in 10+ years—2024 is tracking to be the worst year for VC fundraising since 2015:

The problem is that LPs aren’t getting distributions, so they don’t have much new capital to deploy. Here’s data on 12-month distribution yield relative to net asset value. The TL;DR—in 2020 and 2021, LPs were getting a lot of money back, which they could channel into new deployments. Now, not so much. We haven’t seen this low a ratio in ~15 years:

Many LPs are also overexposed to venture, suffering from the so-called “denominator effect.” LPs like Stanford’s endowment or California’s teachers retirement system have exposure to both public markets and private markets. As the public market goes through a downturn, public assets decline in value; consequently, LPs become relatively overexposed to privates. This is the denominator effect. Put simply, they don’t need more venture exposure right now.

I expect the tide to soon shift—this past year was probably the worst of it. But the market downturn also isn’t all bad…

The Daybreak “Why Now”

The tough market environment is also part of the “why now” for starting Daybreak. I’d break that “why now” into three components.

“Why Now” #1: Market Downturn + Talent Unlock

Low interest rates and COVID-era money printing powered a bubble in venture capital funding and startup valuations. Companies over-fundraised and over-hired, and then, as interest rates rose, they began to pay the price. (Rising interest rates will always punish tech stocks, as tech stocks are highly dependent on future cash flows discounted to the present.)

A year ago, I wrote:

This is a compelling moment for early-stage investing. Talent is about to be unlocked, which will fuel a boom in startup creation. Looking back at the Great Recession, venture funding declined overall, but cohorts of iconic companies were born—again, all of the mobile and cloud companies mentioned above were founded in the five years of 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2013. These next five years—2024, 2025, 2026, 2027, 2028—may be historic vintages for Seed.

This thesis is playing out: both the quantity and the quality of early-stage startups is rising, and I expect this trendline will only continue. Talent is being unlocked.

“Why Now” #2: Tech Shift + Behavior Shifts

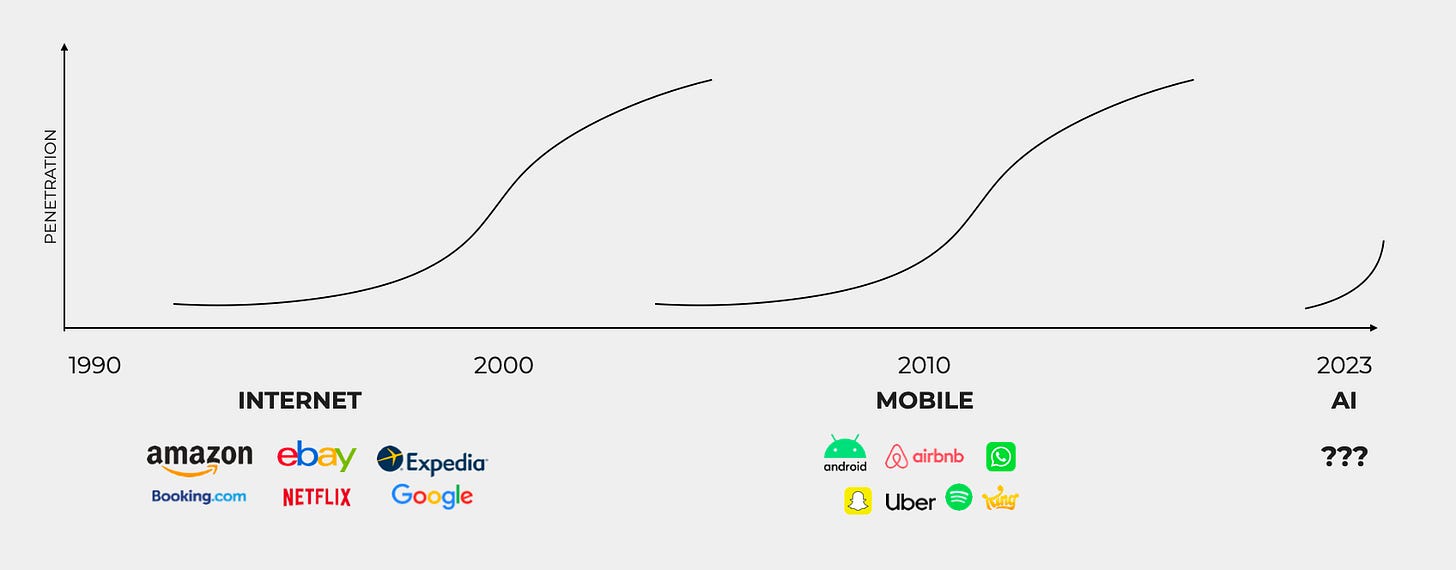

A year ago, we also noted that we’re seeing a unique collision of major shifts in technology and behavior. AI is the obvious shift, and I do think we’re still early in the days of AI’s emerging application layer. (The Mobile Revolution vs. The AI Revolution made this same argument.)

But we also see big behavior shifts from an emergent generation—new attitudes toward work, a newfound emphasis on health and wellness, the growing importance of sustainability. These behavior shifts interact with enabling technologies to form startup opportunities.

A common theme in Digital Native is that the biggest startups are born from the intersection of a technology shift and a behavior shift. Three examples we’ve often cited:

Robinhood rode a technology shift (mobile) that intersected with behavior shifts around people becoming more financially educated, motivated, and independent in a post-Great Recession era.

Instagram also rode the rise of mobile, including rapidly-improving smartphone cameras. At the same time, people were learning to live more public lives, build parasocial relationships, and cultivate global communities / social graphs untethered from geographic constraints.

Figma, meanwhile, rode a technology shift in WebGL (released in 2011, WebGL let you render interactive graphics in the browser) alongside the increasing importance of design in a digital world and the expanding definition of “designer”—online, everyone was becoming a designer.

What’s next?

Many of our Daybreak companies build on such intersections. To take three examples of companies still in Stealth:

I continue to believe that we’re seeing both technological disruption and cultural disruption, which create openings for massive innovation.

“Why Now” #3: Artisans vs. Asset Managers

The third “why now” for Daybreak is the broader state of the venture landscape.

Above, we noted that the market downturn will lead to the extinction of many over-capitalized companies. I expect we’ll also see the extinction of many venture firms. Josh Wolfe recently predicted that 30-50% of venture firms may cease to exist. The industry is consolidating around a handful of names—firms that increasingly resemble asset managers like Blackstone or BlackRock—and LPs are enabling this consolidation: earlier this year, PitchBook reported that two firms (a16z and General Catalyst) had vacuumed up 44% of all LP dollars.

In March’s Two Roads Diverged, we argued that venture is cleaving into two halves: the asset managers and the artisans. The former target private equity-like returns, using capital as the weapon; the latter target outsized venture-like returns and center around talent, acting more craftsman-like and truer to the original ethos of VC.

Misaligned incentives in venture aren’t surprising; from that March piece:

We’ve seen an “industrialization” of venture capital. What was once a cottage industry went into overdrive. The product became mass market. It’s not hard to understand why venture ballooned as an asset class: (1) ZIRP drove a huge influx of return-hungry capital into PE and VC, and (2) incentives drive larger funds.

Here’s a good example of why incentives are skewed in venture:

The net present value of management fees alone for a fund at $1,000M exceeds the fees and carry of a fund at $200M, even if it returned 4x. Let that sink in. Bigger funds means more fees, and more fees mean that GPs get rich, regardless of performance.

Yet the data shows that smaller funds outperform. A study from PitchBook and Sante Ventures found that venture funds smaller than $350M are 50% more likely to generate a 2.5x return than funds larger than $750M.

My friend Kyle recently tweeted a quote from USV’s Fred Wilson:

This is the “why now” for Daybreak. As behemoths like a16z and GC scoop up more capital, they leave behind a gap—a gap for a new cohort of disciplined, focused, hands-on early-stage firms.

The Daybreak Portfolio

The most important update from the past 12 months: we’ve invested in 10 companies. I couldn’t be more thrilled with the caliber of founders we’ve backed.

We’ve led or co-led the majority of our investments (Pre-Seed and Seed) and we’ve been quite disciplined on price and ownership—when we invest time and resources into a company, the math needs to work to allow for the power law of venture. This means saying no to some “sexy” high-priced Seeds, instead focusing on being first capital in to companies with enormous upside.

Why stay disciplined on price?

Last spring we did an exercise in Digital Native where we looked at a sample portfolio for a Seed fund like Daybreak. To revisit it here:

Say we make 30 investments of $1M each, averaging 10% ownership. In order to deploy $30M, you actually need a fund larger than $30M to account for fees and expenses—probably in the $35-40M range, depending how much you get back from recycling. Let’s call this fund $35M for simplicity.

Here’s what the distribution of outcomes might look like for Companies 1 through 30. Six companies return capital; the rest are zeroes.

This speaks to the power law, and you can see why ownership is important. This model assumes we take 50% dilution by exit, so our 10% becomes 5% ownership. If we entered with only 5% ownership, the 6.0x fund becomes a 3.0x fund. If we can manage 15% initial ownership instead of 10%, we rise to 8.9x. (All these returns are gross, by the way, not net.)

Of course, the math above is hugely oversimplified. This basic model doesn’t take into account reserves for follow-on investments, for one, or about a dozen other variables. But it makes the point: when it comes down to it, this job is about (1) good ownership in (2) great companies. That’s about it.

The loss ratio modeled above is conservative; good venture firms typically have much lower loss ratios (around 50%). But returns are almost always clustered around a few home-runs.

What if a Seed fund like Daybreak can be in the next Figma, Snap, Roblox, or Unity? That’s the goal. In that case, even if we have 29 companies return zero (a 97% loss ratio!), the one winner powers a 14.3x fund. This is the beauty of a small fund.

Of our 10 companies:

6 are based in New York

3 are based in San Francisco

1 is based in Los Angeles

And one of the things I’m proudest of: the diversity of our entrepreneurs. We’ve started reporting these metrics in our quarterly LP updates, and we plan to keep to doing so. This is an industry in which female-led companies raise <3% of venture capital and companies led by a Black founder raise <1% venture capital. We track metrics to make sure we’re putting our money where our mouth is, and view this as a key piece of shifting VC’s diversity problem—a responsibility that capital allocators should bear.

Of our 10 companies:

5 female-led companies (female CEO), 50% of Daybreak portfolio

1 Black-led company (Black CEO), 10% of Daybreak portfolio

17 founders overall: 7/17 female (41%), 8/17 non-white (47%)

DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) isn’t as talked-about as it was a few years ago—there’s even a growing backlash to DEI initiatives—but venture’s lack of diversity continues to be a glaring sore spot for the industry. With startups acting as determinants of the future, lack of diversity in entrepreneurship trickles downstream into lack of diversity in the broader economy and culture. As an industry, we can’t improve what we don’t measure, and we can’t fix what we don’t talk about.

Sourcing

When it comes to sourcing great founders, we largely rely on founder, angel, and investor referrals. If we do our job right, we earn founder references—which in turn power more referrals, turning the flywheel faster.

Many referrals stem from someone in our network who reads a thesis piece—say, on mental health or sustainable commerce—and then makes an introduction to a founder building in that space. I don’t think a VC can rely solely on content for sourcing, but this is a job about manufacturing serendipity—how do you stay top-of-mind for the next great founder when she goes to raise her round? Writing weekly long-form thesis pieces is a way to remind people what you’re interested in and to stay top of mind week in and week out.

I also believe that you can be thesis-informed, but should be founder-centric. Forming a point of view on a market or business model is helpful—but it always comes down to an exceptional founder. In my view, ideas are a commodity; everything is about execution, and execution is all about the entrepreneur.

Over Year 1, we’ve invested in some areas in which we’ve long wanted to make an investment. In other areas, we’re still holding out for the right team.

Delivering for Founders

I tend to think of delivering for our companies in three buckets: (1) designing business model and product roadmap, (2) cracking distribution, and (3) attracting early talent. The final bucket is most measurable—for example, we can track that we were able to source and close key hires for our companies; recent examples:

Head of Growth for the company mentioned in The Telehealth Tipping Point

Head of Ops for the company mentioned in The Future of Creator Commerce

First Ops hire for the company mentioned in Combatting the Teen Mental Health Crisis

Introducing the two co-founders of the company mentioned in The Resale Revolution

Sometimes other aspects of working with our companies can also be measured (we’ve named two of our companies!) but most of the time this part of the job is less quantifiable (e.g., are you your founder’s first call when the going gets tough?).

Final Thoughts: Where Are We Going?

There’s a difference between building a fund and building a firm. Probably the most asked-about slide in our fundraising deck is a slide that focuses on the long-term vision for Daybreak—how we evolve into Fund II, Fund III, and beyond.

Daybreak will grow over time, but we’ll remain lean and we’ll always skew more craftsman than asset manager. Our thinking is to scale fund sizes while steadily increasing target ownership, adding roughly one Partner per fund.

I’m sure I’ll regret putting this in writing. In fact, now that I’ve written it here, we’re almost guaranteed to change this thinking 🫠 But this is the current vision, subject to future learnings that will inform and refine it. We’ll grow over time, but the key word will always be “artisanal.”

Year 1 has been good. The “why now” is playing out, in terms of this being the right moment to start a venture firm. Our companies are maturing nicely, and our positioning in the market seems to resonate with founders.

Yet we still have a long (long) way to go. Last year’s announcement concluded with this paragraph:

As far as Digital Native goes, nothing will change—I’ll continue writing long-form pieces week in and week out. That said, I’ll weave in some new learnings from investing at the earliest stages, from running a venture capital fund, and from continuing as an anthropologist of sorts, studying how people and technology shape one another.

I’ll continue to keep that promise, and will do periodic updates (maybe a couple times a year) to continue building in public.

We’ll be back next week with a more typical Digital Native!

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: