Daybreak: The Two-Year Update

Reflections on Sourcing, Picking, Winning, and Partnering

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 70,000+ weekly readers by subscribing here:

Daybreak: The Two-Year Update

We started Daybreak two years ago this month. Last year, I wrote a reflection on our progress a year into building the firm; this week, I want to do a two-year update.

I’m a big believer in building in public, both as a forcing function for intellectual honesty and as a way to bring transparency to an opaque industry. Hopefully this piece achieves both those goals!

People often break venture into four “jobs within the job”—

Sourcing—Can you find the founder / company?

Picking—Can you diligence the opportunity effectively?

Winning—Does the founder pick you?

Partnering—What value can you add over the life of the company?

There’s a less-spoken-about and equally important 5th component, Exiting, that’s sometimes forgotten today, much to LPs’ chagrin—but let’s leave it at four for simplicity.

I want to structure this update a bit differently: we’ll start with broader reflections on two years of building Daybreak, then dive into my philosophy on each of the four buckets above. Hopefully this is a more interesting “progress report” than just rehashing our portfolio and strategy.

Reflections

Sourcing: Manufacturing Serendipity

Picking: Spotting the X-Factor

Winning: Price vs. Speed & Conviction

Partnering: Creating Moments of Inflection

Let’s dive in.

Reflections

I chose the name “Daybreak” because it has connotations of (1) early, and (2) optimistic. Those connotations fit the core tenets of the firm: we’re the first backer to founders / companies, and we approach venture from an ethos rooted in optimism.

I also remembered reading once that a linguistics study showed the “K” sound to be especially memorable—e.g., Kodak. That was an added bonus. (I later learned that compound words make good names because they bring two different associations—for instance, associations with both the words “day” and “break”—but that unfortunately wasn’t part of the calculus at the time. Also an added bonus!)

I’ve always wanted Daybreak to feel less like a financial services firm and more like a luxury product. Our goal is to be the antithesis to the “asset manager” VC that invests at Seed as option value; rather, we aim to be the world’s best first-check venture firm, more craftsman than asset manager and the most helpful person on the cap table for the first ~2 years of the business. What we’re selling should be a luxury product: deep, artisanal partnership.

This was the cover for our fundraising deck for Daybreak Fund I:

We recently launched a fresh website, which carries forward the same aesthetic—shoutout to Justified for the build; I highly recommend working with them on anything brand or website related:

The site should get across the same connotations behind the name Daybreak: early and optimistic.

We want to be a founder’s first believer, and we’re doing a good job backing this up: we typically invest before the first line of code is written; we’ve introduced co-founders; we’ve sourced founding engineers; we’ve even named companies in the Daybreak portfolio.

When it comes to what we invest in, we like companies reshaping large markets or inventing new markets entirely. In particular, we get excited about companies that make life tangibly better across the major areas of life—health, money, work, etc.

We invest fairly broadly at the application layer: our portfolio is weighted ~70% toward B2B companies and ~30% toward B2C companies right now. I think that’s about the right split. We’re currently leaning slightly toward New York-based companies—home court advantage—but we also have a good number of San Francisco-based companies in the portfolio (as well as a sprinkling of Toronto, London, and LA).

In the early years of a venture fund, you’ll typically see what’s called a J-curve: when a fund begins to invest, money flows out through capital calls and management fees. This results in negative returns initially, before companies begin to perform and the curve upward begins. We’re now safely out of the J-curve for Daybreak Fund I: in the past quarter we’ve had 8 mark-ups in the portfolio, and things are humming. We have a few “winners” emerging, though I’m cognizant that these probably aren’t the companies that eventually become outliers: I hear often from other fund managers that their stack ranking of their top 3 portfolio companies in the early years of the fund life often ends up going 0 for 3 on which companies prove to be the ultimate value drivers.

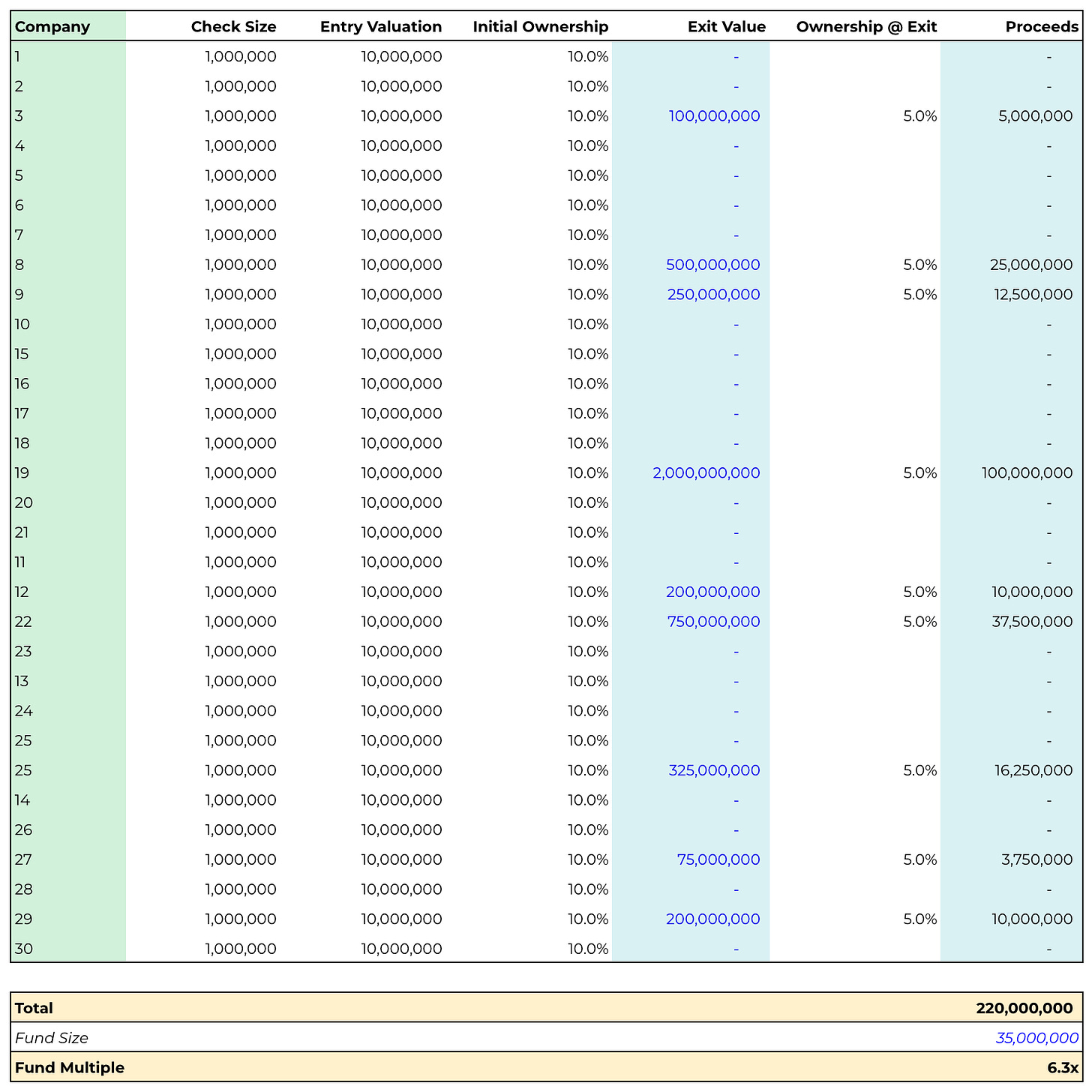

One thing we’ve been disciplined on: trusting the fund math. Over the summer I wrote Fund Math for Dummies to emphasize that basic venture math is broken in this market. In short: ownership matters—and for a $33M Fund I, ownership means being disciplined on entry-price.

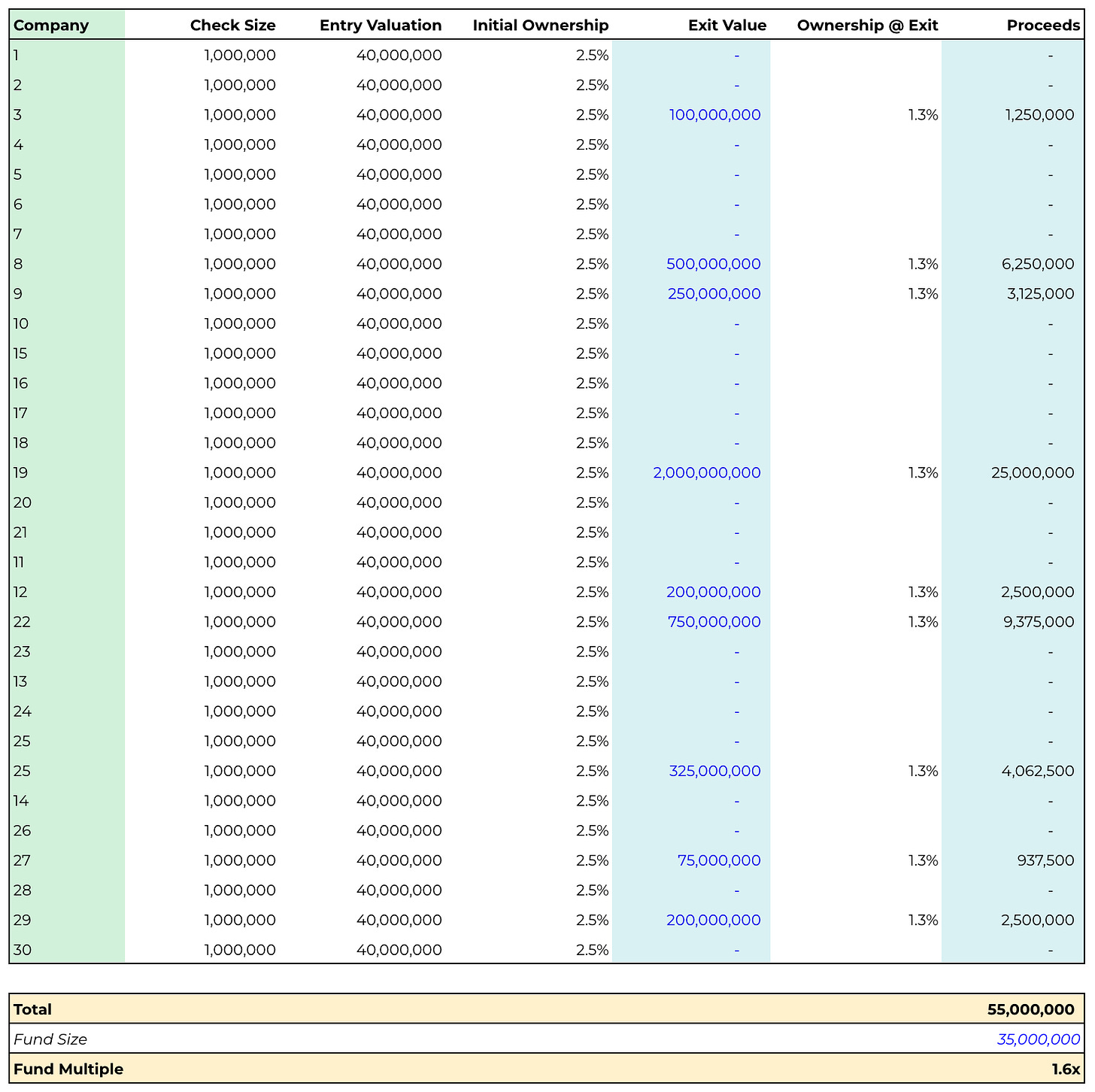

Here’s one example from that piece. Say we invest $1M each into 30 companies. Because of fees, we’ll need a slightly-larger fund—say, $35M for simplicity. We average 10% ownership at entry ($10M post-money valuation) and get diluted 50% to 5% ownership at exit. Here’s one set of outcomes that gets us to a ~6x multiple:

22 / 30 companies return $0, while 8 / 30 produce a range of good to great outcomes.

We’re ignoring a lot here: reserves, recycling, gross multiple vs. net multiple. We’d also probably take on more dilution by exit. But the math gets the point across: a handful of companies drive the lion’s share of the returns. Half the proceeds generated here come from a single company, Company 19. Remove Company 19 and you’re down from a 6.3x fund to a 3.4x fund.

To show why ownership matters: let’s run the same math, but instead of investing at $10M post and getting 10% ownership, we invest at $40M post. We get 2.5%, diluted to 1.25% by exit. We go from a 6.3x fund to a 1.6x fund. Yikes.

In my view, the mistake that Fund I’s make (especially spinouts from top-tier venture brands) is that they want to be in the “hot” deals but they aren’t disciplined on the fund math. It’s hard to return your fund on 1% ownership, even if you get into a generational company.

We’ll launch Fund II next year, and we’ll keep much of the same strategy: Pre-Seed and Seed as our bread-and-butter, investing early with high-conviction and delivering a “luxury product” to founders. We’ll increase a few levers—fund size, average check size, reserves, etc.—but we’ll keep the fundamentals the same.

Now, quick thoughts on the four “jobs within a job” of venture.

Sourcing = Manufacturing Serendipity

I’m often asked, mostly by LPs, which of Sourcing, Picking, Winning, and Partnering we can most improve at. The answer is always the same: Sourcing.

You can always be better at sourcing, and you never feel “good” at it. If you see and win a competitive deal this week, you’ll inevitably hear about another one you missed. The good news is, you don’t need to see everything in order to have great returns. But the better your coverage, the better your chances of being in the companies that matter.

My philosophy toward sourcing in venture is that it’s about manufacturing serendipity. What does that mean? In other words: how can I increase my surface area for luck, so that I maximize the odds of a generational founder being told they have to meet Daybreak?

In venture, you have to stay top of mind. Every time a great founder goes out to raise, I want three people whispering in her ear, “You have to meet Rex at Daybreak.” One effective strategy for this is content; writing Digital Native for 70,000+ subscribers each week means 70,000 people are reading our stuff and being reminded Daybreak exists. In a sales job (and venture is a sales job), that’s important. As a bonus, the topic for each piece hits people over the head with a reminder of the themes I’m interested in. Thanks for putting up with that :)

Two of the investments we’ve made this year have come directly from Digital Native readers responding to a piece: one in response to February’s How AI Changes Customer Acquisition, the other in response to April’s The Third Workforce: From Analog Labor to Agentic Labor. Side note: I don’t typically view content as effective without being combined with a strong network. Content is a better tool to keep warm an already high-quality network, rather than to create a network from scratch.

Content isn’t the only effective strategy. Maybe you want to be at every conference and networking event. (Only moderately effective, in my mind: most great founders aren’t at these events.) Or maybe you want to be hanging out at every hacker house. (More effective.) There are plenty of ways to manufacture serendipity. But you need to figure out how to stay top of mind, and how to stay in the flow of information.

By the way, this isn’t just true in venture; it’s true in any sales job.

Picking = Spotting the X-Factor

When I pitch an LP and they don’t come into Daybreak, I think to myself: I didn’t do a good enough job convincing them I’m a killer.

Sure, maybe the LP had one slot left in their portfolio and they were reserving it for a biotech fund; sometimes it really is just a mismatch in timing, and you’re not selling what they’re buying. But most of the time, it’s me; I didn’t convince them I’m good enough. A friend of mine likes to say: “Believe the no, not the reason.”

Founders should adopt the same thinking, at least for the earliest stages of a company. At Pre-Seed and Seed, it’s really all about the founder(s). Yes, a company needs a large market, an attractive business model, and smart timing—but the best founders tend to pick good markets, business models, and “why nows.”

I used the word “killer” because it’s effective at capturing whether a founder has a certain ambition and grit. Doug Leone of Sequoia talks about using that word. I do think “killer” can capture a bit too much of the Silicon Valley founder stereotype: hard-charging, aggressive, typically white, typically male. The Travis Kalanick type in HBO shows.

So I often prefer “x-factor.” What’s this founder’s x-factor, and why will it make them successful in this business? Different types of companies might have different x-factors. A consumer internet company might need a growth mastermind. A B2B healthcare company might need someone who spikes in sales. A deeply technical product might need a strong engineer, and so on. But regardless of sector, x-factor should always capture grit, intellectual horsepower, and depth of insight.

Winning = Price vs. Speed & Conviction

Winning, to me, is about two things: (1) does the founder like you, and (2) does the founder believe you’re going to help them build a big business?

A 2007 Princeton study looked at the word charisma, trying to suss out the traits that make people perceive others as charismatic. The study found that charisma stems from the combination of two other traits: (1) warmth, and (2) competence. Those are pretty good analogs for the two questions above. You need to be likable (the founder is going to have to work with you for a decade) and you need to be good at what you do (after all, this is a business relationship and the founder wants to maximize their odds of success). Winning in venture comes down to convincing an entrepreneur of those two qualities.

And one belief for emerging managers (aka new firms): if you can’t win on price, you’d better be winning on speed and conviction. It’s hard for a $33M fund like a Daybreak Fund I to outbid a multi-stage firm if they’re hot on a company. But where they have bureaucracy, we have agility. Moving fast and with conviction is still surprisingly rare in venture.

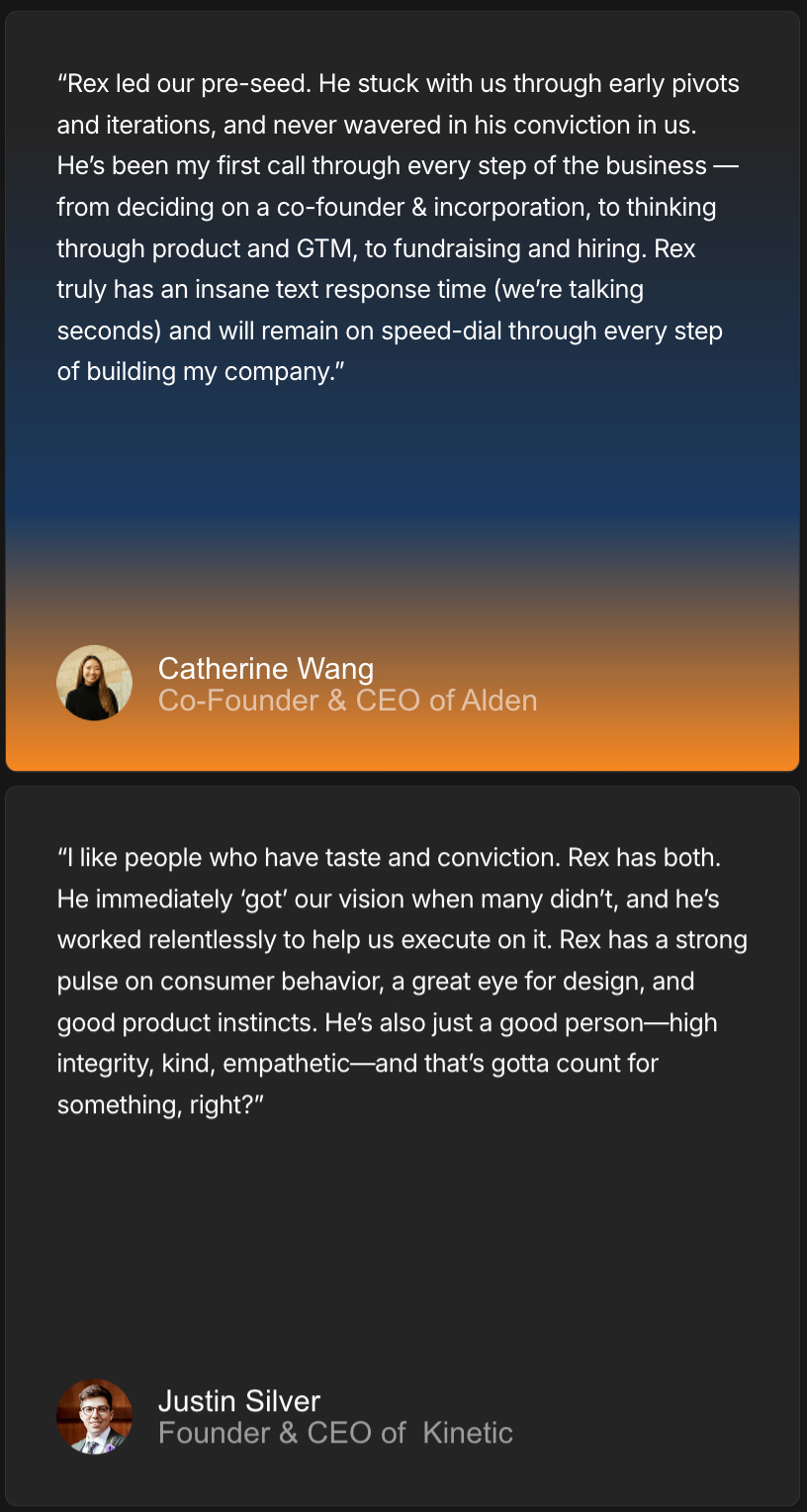

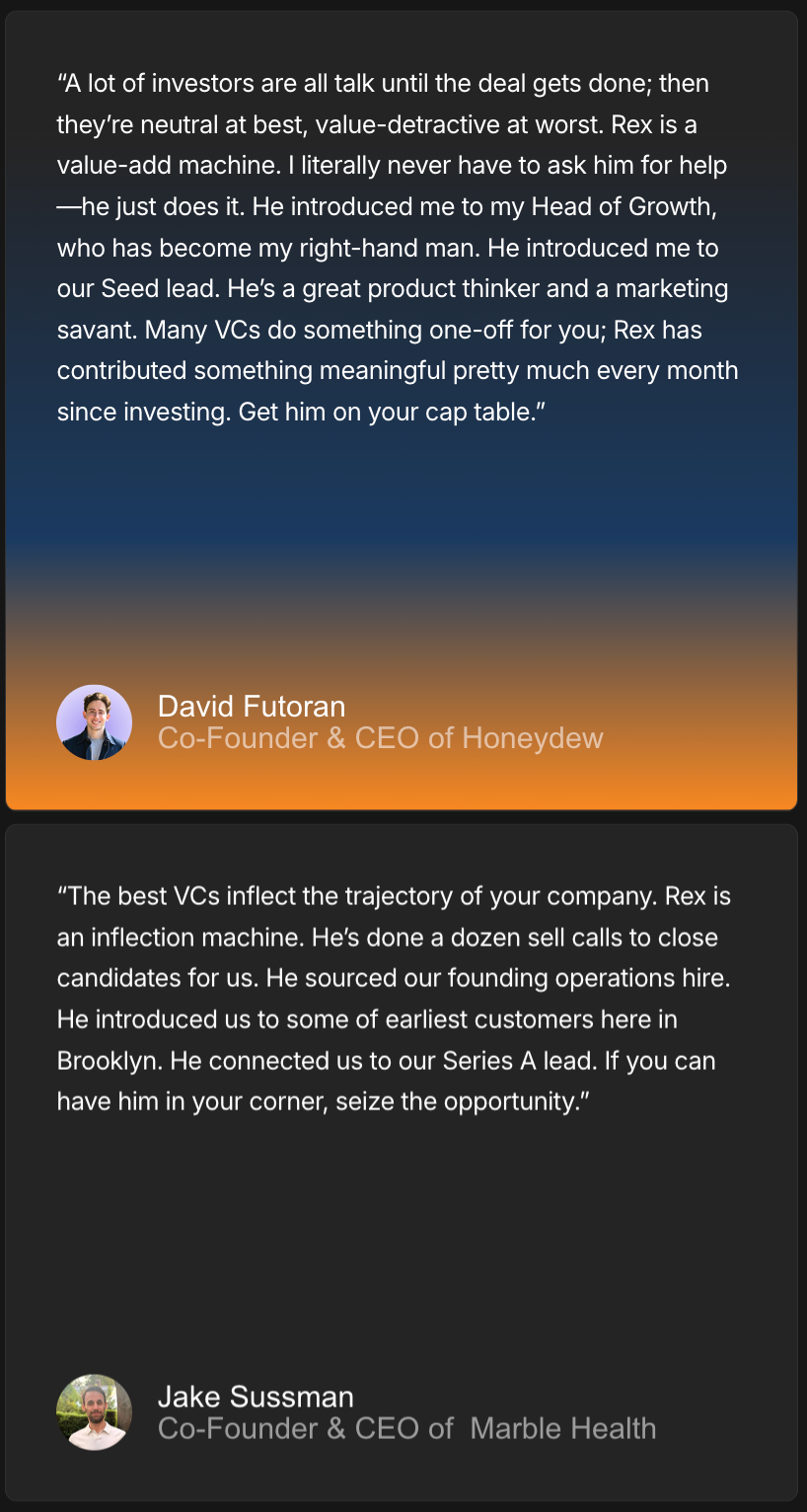

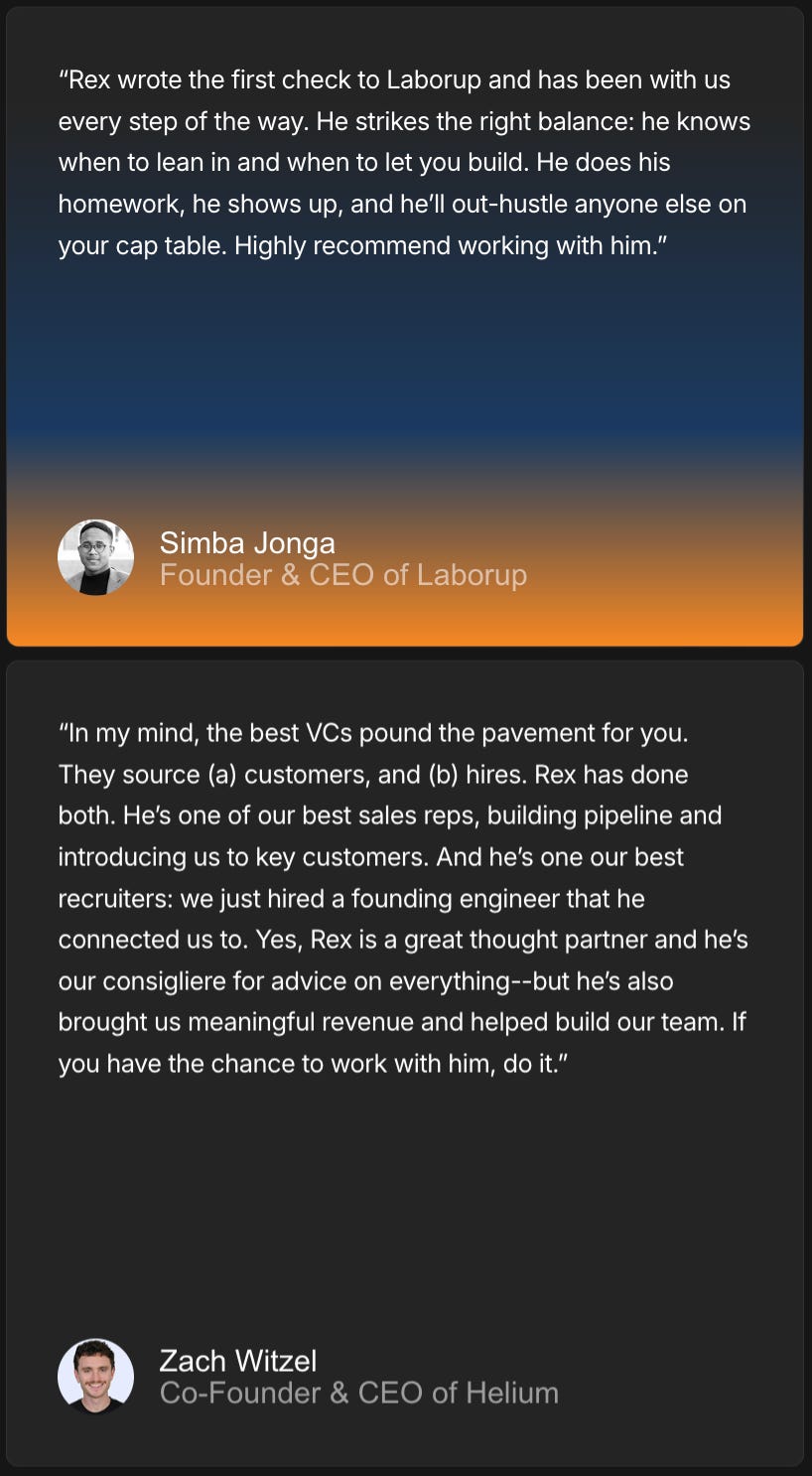

Partnering = Creating Moments of Inflection

A question I like to ask when thinking about backing a founder: can this founder build a big business without me?

It’s not your job as a VC to tell the founder how to build a $10B company. It’s your job to figure out the key ways you can increase the odds of that happening by 1%, 2%, 3%.

Partnering with a company means creating moments of inflection for the business. Inflections can come from a key insight on product or business model. They can come from introductions to a key customer, to a helpful angel / advisor, or to downstream capital. Often the best thing you can do for a company is help them hire great talent— over the past month, we’ve helped source:

Head of Product

Head of Growth

Founding Engineer

2nd Engineer

To four of our companies. Hopefully we can do even better this month. Eventually, we may build out a talent function to formalize this recruiting engine, but I’m still thinking through what that might look like.

The TL;DR is: the best founders know what they’re doing, and don’t need much help. But a good VC will still find ways to move the needle, not by being overbearing but by creating inflection moments that shift the company trajectory.

What am I most proud of in two years of Daybreak? Delivering for our founders. Hopefully we can keep raising the bar here, as our team grows and we get more resources and capabilities to work with.

By the way, the most helpful thing I can do is find great engineers for our companies. We have fast-growing companies hiring in-person engineers in New York and San Francisco—the ideal engineer has a few years of work experience (ideally at a startup) and is hungry to join something early and work in person from the office.

Shoot me an email at rex@daybreakventures.com 📬 if you have a great NYC or SF engineer who could be a fit. As a bonus, most of these companies are offering $20K referrals if you introduce an engineer who ends up joining! Appreciate any leads on great folks.

Final Thoughts

It makes me squirm that the “I” pronoun features so heavily in this piece. Our goal over the next year is to turn Daybreak from a one-man operation into a firm, with a growing team. This firm isn’t called Woodbury Ventures for a reason, and I hope Daybreak outlives me.

We’ll add another investor within the next quarter or two, and potentially another 1-2 team members before this time next year. By September 2026, our “three-year update,” we’ll have activated Fund II and will be evolving into a real firm, not a solo GP shop.

We’re still a startup ourselves, and we have a long way to go. When we started, I committed to building in public (here’s our “launch” piece from two Septembers ago) and we’ve kept that commitment. I’ll aim to write another “progress report” next September, and sporadic updates in the interim.

In the meantime, open to any and all feedback / wisdom / insights, and we’ll be back next week with a more typical Digital Native!

Related Pieces:

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: