Daybreak: Building a Venture Capital Firm

A Progress Report on Daybreak: the "Why Now," Investment Thesis, & Portfolio Construction

Weekly writing about how technology and people intersect. By day, I’m building Daybreak to partner with early-stage founders. By night, I’m writing Digital Native about market trends and startup opportunities.

If you haven’t subscribed, join 60,000 weekly readers by subscribing here:

Daybreak: Building a Venture Capital Firm

When I started Daybreak last summer, I registered the fund under Rule 506(c).

The industry norm is to wait to talk about a venture capital fund until after the fund closes; this is because firms can’t generally solicit investors or advertise for a fund. But Rule 506(c) allows a fund manager to publicly talk about a fund in parallel with fundraising. (The downside is a bit more paperwork: every limited partner needs to sign an Accredited Investor certification letter.)

Rule 506(c) allowed me to lay out the vision for Daybreak last September in Daybreak: Venture Capital for the Next Generation. It allowed me to use a Google Form to bring in members of the Digital Native community as LPs, broadening access to venture. And it’s allowed me to periodically mention our companies and strategy in Digital Native pieces over the past months.

The thinking was: venture capital is already too much of a black box. Founders—and even many venture investors—don’t get much of a window into the inner-workings of a fund. Our goal with Daybreak has always been to build in public and to offer transparency.

This week’s piece acts as a status update on Daybreak. We have a new website launching today:

And it’s been a productive eight months since that launch piece in September. We’ve made 8 investments and just had our first mark-up. I’m thrilled with the quality of founders we’ve backed, and in my mind, we’re delivering on our promise of hands-on partnership.

Q1 2024 was a good quarter: we made three investments, each a $750K check and averaging 9.2% ownership, which I’m pleased with. More on portfolio construction and ownership targets later in this piece.

I’m also proud of our progress on other metrics I care about. Here’s an excerpt from the Q1 letter I sent out to LPs, tracking founder diversity:

We’re doing well here, but still have room for improvement.

DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) isn’t as talked-about as it was a few years ago—there’s even a growing backlash to DEI initiatives—but venture’s lack of diversity continues to be a glaring sore spot for the industry. With startups acting as determinants of the future, lack of diversity in entrepreneurship trickles downstream into lack of diversity in the broader economy and culture. As an industry, we can’t improve what we don’t measure, and we can’t fix what we don’t talk about.

This week’s piece focuses on a few topics:

Daybreak: “Why Now?”

Portfolio Construction

Daybreak Investment Focus

The 5 Traits of the Best Founders

Asks of the Digital Native Community

Let’s dive in.

Daybreak: “Why Now?”

Over the past decade, we saw an “industrialization” of venture capital. What was once a cottage industry went into overdrive. It’s not hard to understand why venture ballooned as an asset class: (1) zero interest rate policy drove an influx of return-hungry capital into PE and VC, and (2) incentives drive larger funds. These factors led the venture product to go mass market.

Here’s a good example of why incentives are skewed in venture:

The net present value of management fees alone for a $1,000M fund exceeds the fees and carry of a $200M fund, even if the latter returns 4x. Let that sink in. Bigger funds means more fees, and more fees mean that GPs get rich, regardless of performance.

Last month’s Two Roads Diverged argued that we’re now seeing a cleaving of venture into two groups: the artisans and the asset managers. At its simplest, business boils down to allocating two scarce resources: labor and capital. Artisans focus primarily on the former—on people, through hands-on partnership. Asset managers, meanwhile, are capital allocators, with a lower-touch approach to their companies.

Daybreak fits in the first camp. Our thesis is that the industrialization of venture has left a gap for artisans who are laser-focused on early-stage and who work closely with founders in the first few years of company building.

Daybreak will grow over time, but we’ll remain lean and we’ll always skew more craftsman than asset manager. Our thinking is to scale fund sizes while steadily increasing target ownership, adding roughly one General Partner per fund.

I’m sure I’ll regret putting this in writing. In fact, now that I’ve written it here, we’re almost guaranteed to change this thinking :) But this is the current vision, subject to future learnings that will inform and refine it. We’ll grow over time, but the key word will always be “artisanal.”

The gap in artisanal venture is one half of the “why now” for Daybreak. The other half is a confluence of three shifts:

➡️ Technology platform shift(s), coinciding with

➡️ Large-scale cultural and behavior shifts, all underpinned by an

➡️ Enormous talent unlock driven by the market correction.

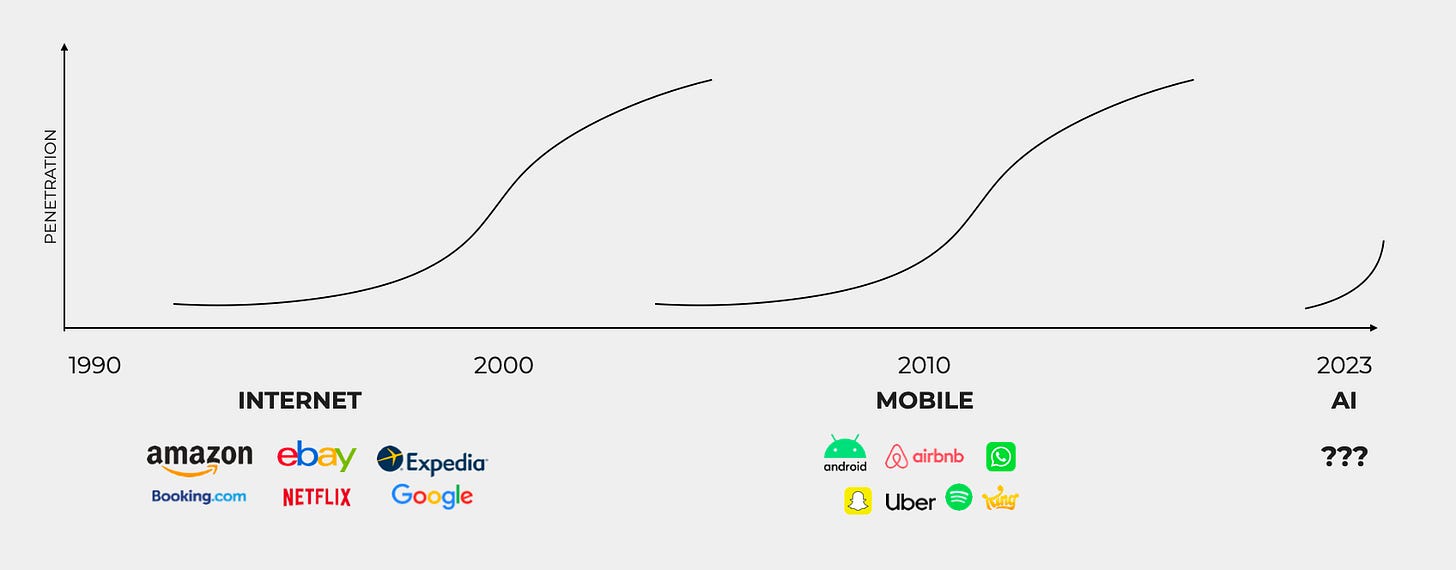

We’ve seen in past technology eras that iconic companies tend to be built in the early years of a big shift. We saw this play out with the internet, which gave birth to companies like Google, Amazon, and Expedia. We saw it again with mobile, which underpinned Uber, Snap, and Android. And we’re seeing it happen again with AI.

The five years of 2023-2026 will be historic vintages for startup creation. The visual above spells out of a helluva “why now” for investing today in the application layer of technology.

Last fall’s The Mobile Revolution vs. The AI Revolution delved deeper into how this moment fits into the broader history of technological innovation; the crux is that we’re likely at the beginning of a new 50-year technology cycle, the first new cycle we’ve seen since Intel developed the microprocessor in 1971. (Microprocessors were manufactured with silicon, giving Silicon Valley its name; the rest is history.)

Technology shifts are colliding with massive behavior shifts, as the digitally-native generation comes of age. This new generation is sending shockwaves through everything from mental health, to sustainable commerce, to gaming, to the meaning of work. When tectonic shifts in technology and behavior collide, large businesses get created.

All of this is underpinned by a market downturn. Market corrections have historically been good moments for early-stage startups, as volatility in the market creates a talent unlock. That talent unlock in turn fuels a boom in startup creation.

Looking back at the Great Recession, venture funding declined overall, just as it is now. But cohorts of iconic companies were born. That downturn also coincided with new technology shifts—mobile and cloud—and we saw the birth of generational businesses. Mobile gave us Uber and Lyft, Instagram and Snap, Robinhood and Coinbase. Each was founded between 2009 and 2013. And cloud gave us Slack and Figma, Stripe and Plaid, Snowflake and Databricks. Again, each was founded in that same five-year period.

Portfolio Construction

Venture is a power law business; one winner can return a fund many times over. Ideally you have two, three, four big winners. This is the business of not what can go wrong, but what can go right.

When it comes to a smaller fund, there are many ways you can slice top-decile returns. There’s an old adage: “There are a dozen ways to 10x a $30M fund; there’s only way to 10x a $3B fund.” What do we mean by that?

Running the math, a $3B fund needs to invest in two $10B companies—and own 15% of each at exit—to simply return the fund. That’s a tall task. Yet owning 15% of a single unicorn—in a portfolio of 30 companies—would 5x that $30M fund on one investment (not accounting for dilution). Or a more distributed set of outcomes—say, five companies exiting at $200M each—would also result in a 5x fund. There are many ways to dice it. You get the picture.

Let’s take a sample portfolio for a Seed fund like Daybreak. Say we make 30 investments of $1M each, averaging 10% ownership. In order to deploy $30M, you actually need a fund larger than $30M to account for fees and expenses—probably in the $35-40M range, depending how much you get back from recycling. Let’s call this fund $35M for simplicity.

Here’s what the distribution of outcomes might look like for Companies 1 through 30. Six companies return capital; the rest are zeroes.

This speaks to the power law, and you can see why ownership is important. This model assumes we take 50% dilution by exit, so our 10% becomes 5% ownership. If we entered with only 5% ownership, the 6.0x fund becomes a 3.0x fund. If we can manage 15% initial ownership instead of 10%, we rise to 8.9x. (All these returns are gross, by the way, not net.)

Of course, the math above is hugely oversimplified. This basic model doesn’t take into account reserves for follow-on investments, for one, or about a dozen other variables. But it makes the point: when it comes down to it, this job is about (1) good ownership in (2) great companies. That’s about it.

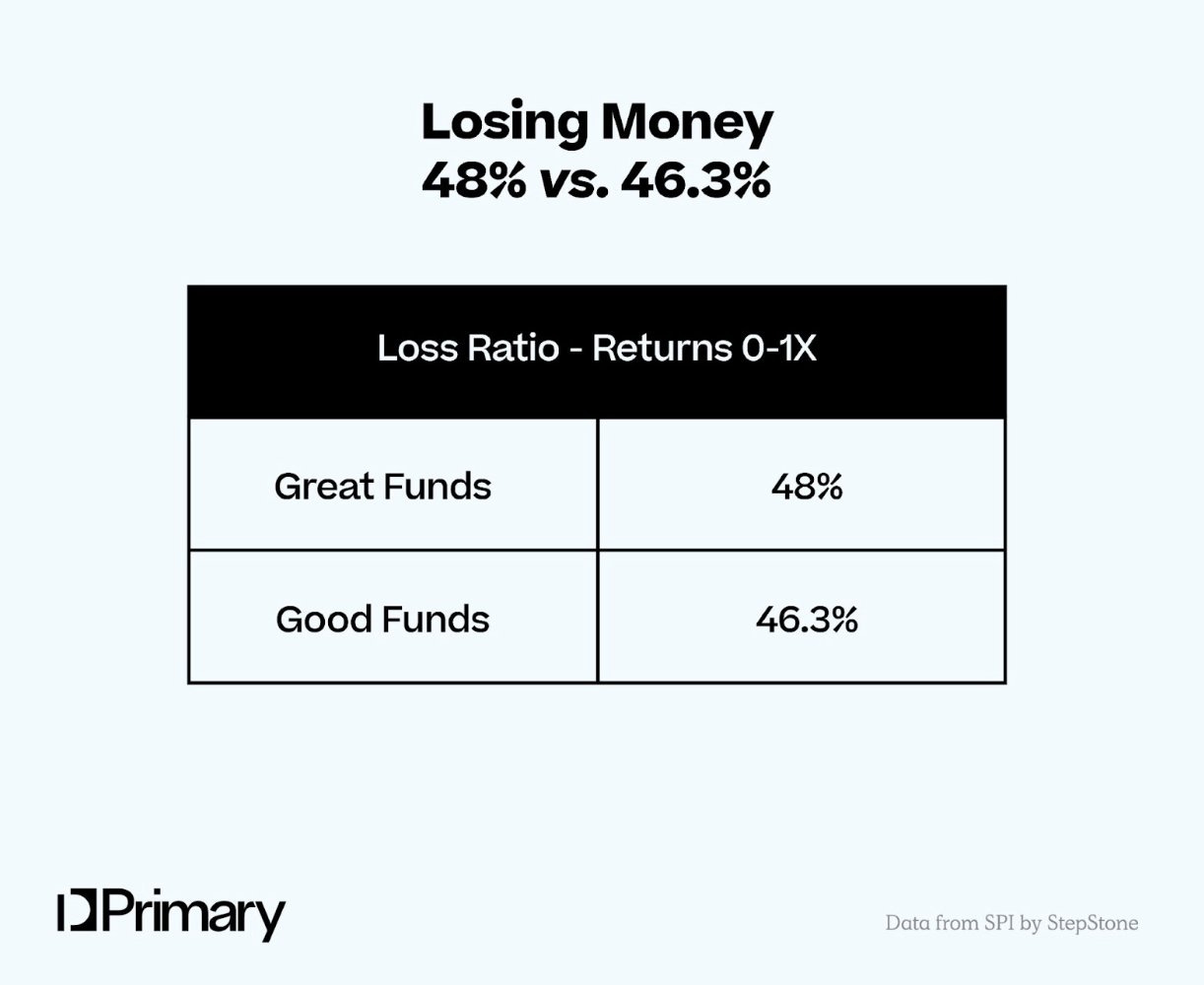

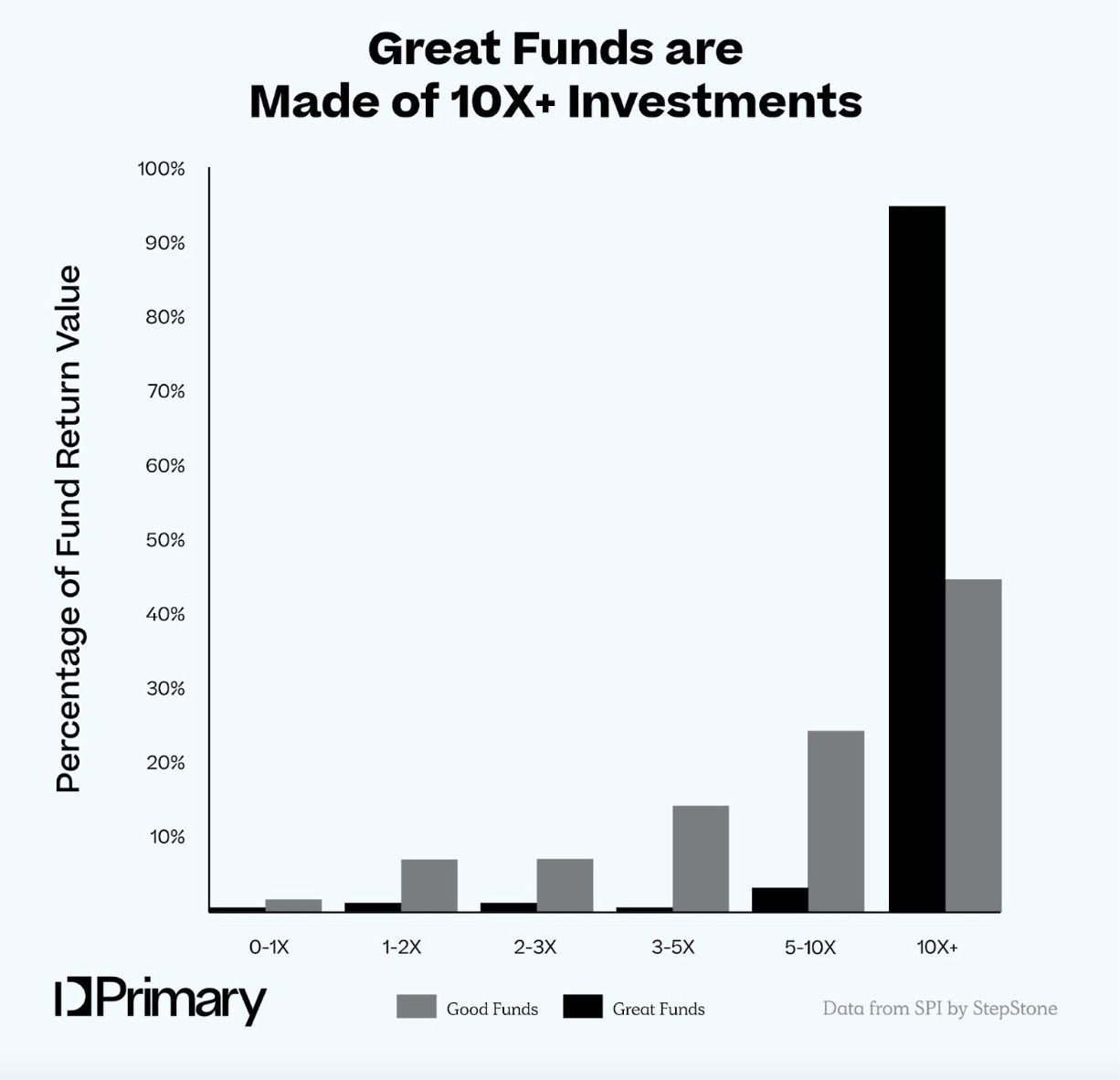

The loss ratio modeled above is fairly conservative; good venture firms typically have much lower loss ratios. My friend Jason at Primary put together a good dataset on fund performance. Top-performing funds actually have slightly higher loss ratios than “good” funds, but both hover just below 50%.

The same 30-company portfolio above can have similar performance with more evenly-distributed outcomes. Maybe instead of six “winners,” we have 14 of 30 companies return capital with more modest returns. But this is less likely, in my mind. Typically, the vast majority of returns are clustered in just a handful of companies.

“Great” funds get 90%+ of returns from 10x+ investments—big home runs.

What if a Seed fund like Daybreak can be in the next Figma, Snap, Roblox, or Unity? That’s the goal. In that case, even if we have 29 companies return zero, this one winner powers a 14.3x fund:

There are 48 decacorns ($10B+ companies) in the private markets; the job of the early-stage investor is to be in one of them.

An AngelList study back in 2021 found that a Seed-stage startup has a 2.5% chance of becoming a unicorn—so about 1 in every 40 companies hits a $1B valuation. Of course, that dataset was from the frothy bull market and has always seemed optimistic to me. Either way, our assumption above is that our initial sample Seed portfolio outperforms the market, with two unicorn outcomes among 30 companies.

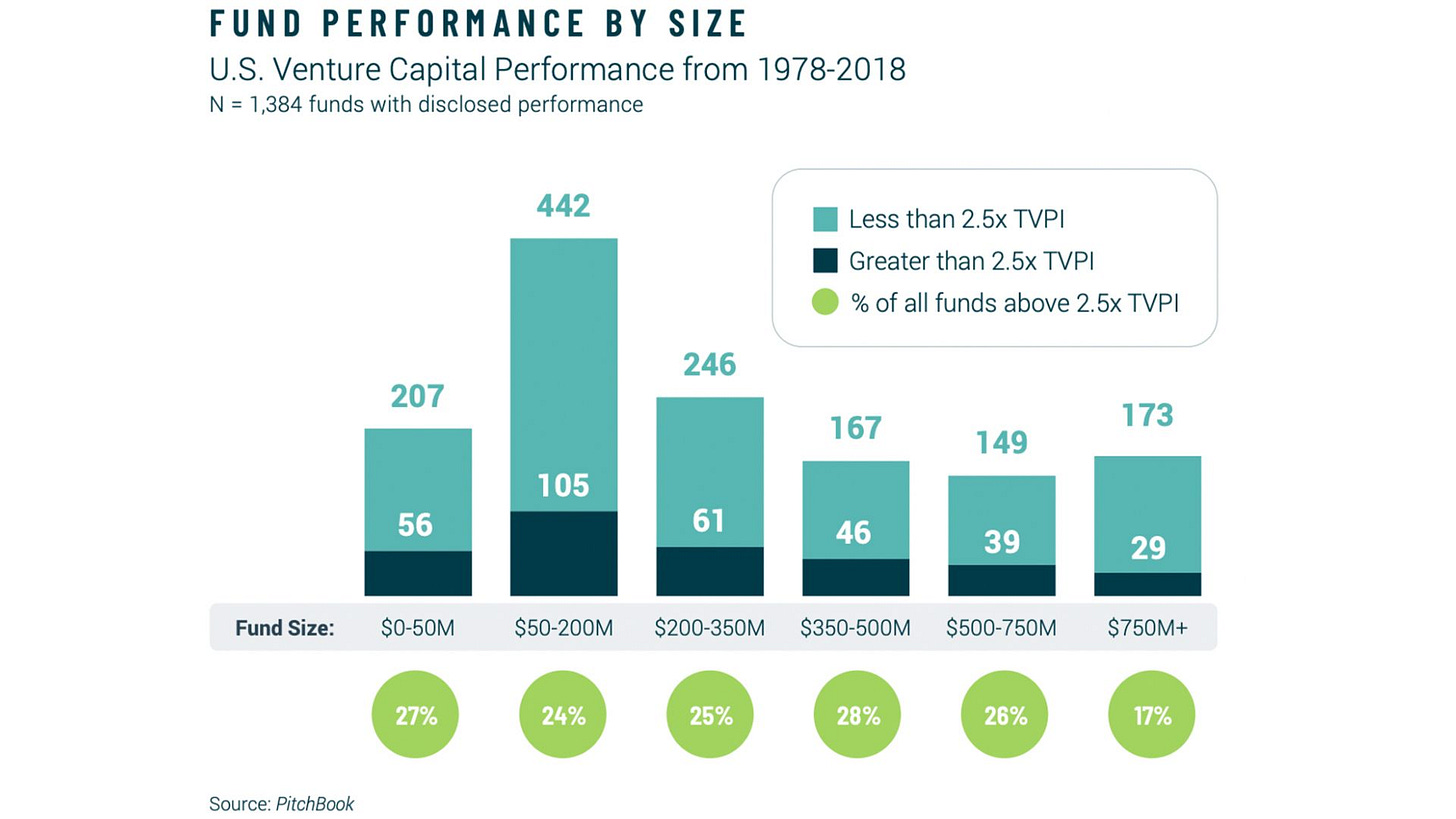

Data has shown again and again that smaller funds outperform. A recent study from PitchBook and Sante Ventures found that venture funds smaller than $350M are 50% more likely to generate a 2.5x return than funds larger than $750M.

The data also supports first-time fund outperformance; so-called “emerging managers” are proven to outperform more established funds.

I expect we see a return of the disciplined, artisanal venture firm. Yet in order to see this return really happen, it needs to start with LP dollars, which have been slow to adjust. Despite smaller fund outperformance, in the first three quarters of 2023, 46.8% of US venture dollars went into funds over $500M. In 2022, that figure was 63.6%. So far in 2024, two firms—Andreessen Horowitz and General Catalyst—have captured 44% of all US VC fundraising.

As LP dollars unlock in the coming quarters (hopefully), we should see a resurgence of the small, agile, focused franchise— the counterpart to the industrialized players raising mega-funds.

Investment Focus

Daybreak’s thesis is that the companies that define the next generation are the companies that make life better for the next generation. Talent wants to work at companies that are mission-driven, and this is particularly true for young talent. When in doubt, follow the talent.

Daybreak invests at the application layer, in internet and software products that have the potential for viral adoption. Companies can be B2B or B2C, but they rarely have heavy top-down sales motions or a strong reliance on paid marketing, and often they have a network effect.

We invest around five core pillars:

Last fall’s The Five Pillars of Startup Impact went deeper into each category. Not every portfolio company fits neatly into one of these buckets, but most do. To take three examples of Daybreak companies:

These companies are in Stealth, but they embody companies making life better for the next generation.

The “Health” company connects teens to mental health professionals through its online marketplace, while building software to provide teens, parents, therapists, and school counselors with a central hub to track care.

The “Sustainability” company connects the moment of purchase to the moment of resale, powering the circular economy for fashion. Globally, fashion comprises 10% of carbon emissions—more than maritime shipping and air travel combined. This company removes friction from resale and improves the lifecycle of goods, combatting fashion’s carbon footprint.

The “Job Creation” company builds software and a labor marketplace for skilled industrials workers—think machinists at Ford or welders at Boeing. There are 10M Americans who work in skilled industrials, but their workflows remain analog and antiquated.

I continue to believe that the decade-defining businesses will leverage technology to solve real problems for people. We’re seeing this play out in the caliber of entrepreneurs building in each of the five pillars above.

The 5 Traits of the Best Founders

My view is that a venture firm can be thesis-informed, but must be founder-first. You get in trouble when you fall too in love with your own projections of where the world is going; the entrepreneurs are the ones building the business. Often, they’re living a year or two in the future and pulling us all toward it. This job is about spotting killer instinct—the steeliness and grit that allow someone to build a multi-billion-dollar business.

I find the best entrepreneurs share five traits:

Founder/Market Fit

“Founder / Market Fit” is an overused term in VC, but it does matter. The question I always ask myself is:

Why is this founder the founder to build this business?

And I often ask the founder:

Out of everything you could be working on, why this?

The best founders have unique work experiences or lived experiences—sometimes both—that give them unfair advantages to build their business. To continue with the three examples from earlier:

The founders of the mental health business have personal experiences with mental health in their families, and also previously built a large mental health startup.

The founder of the resale company is her own customer; she knows the pain of spending her Saturdays photographing wrinkly clothes and cataloging them on Poshmark and Depop. She intimately understands the friction in resale—and she happens to have also built commerce product at one of the most successful startups in that space.

The founders of the company building for skilled industrials workers grew up around those workers in Tennessee; friends and family members are machinists and welders. They’re building for the community they know best.

Clarity of Thought

The best founders can articulate exactly what needs to be built and when. I often ask two questions:

What needs to be built in the next six months?

This is to see how deeply they understand the order of operations for the near future. Even if you’re building a complex network or platform, you’re typically starting with something specific—often a product that solves the most salient pain-point for the user. The early days are sniper-like, and complexity comes later. Articulating that early focus is key.

The follow-up question zooms out:

If everything goes according to plan—green lights all along the way—what will you have built in five years?

This is the opposite—can that near-term plan feed into a long-term vision? How do the pieces fall into place? What’s the master plan? Another question I like:

What keeps you up at night?

I find this reveals a founder’s depth of understanding of their market and product. I love when a founder knows what they don’t know, and isn’t afraid to share that. It gives me confidence that they also know what they know, and that they have self-awareness of their blindspots.

3) Missionary, Not Mercenary

Another cliche is looking for a founder who’s a missionary, not a mercenary. But there’s truth to it. Being a missionary means you can persevere through the (inevitable) tough parts of entrepreneurship. Being mercenary isn’t bad; it’s good to be motivated by success and money. But it’s often not enough, and should be underpinned by a deep love for the customer and a deep belief in the product.

A question to think through, that helps suss out whether someone is a missionary:

Would this founder still build this company if they couldn’t raise capital? (Or if they couldn’t raise capital from a top firm?)

In other words, are they a tourist, or are they set on willing this company into existence?

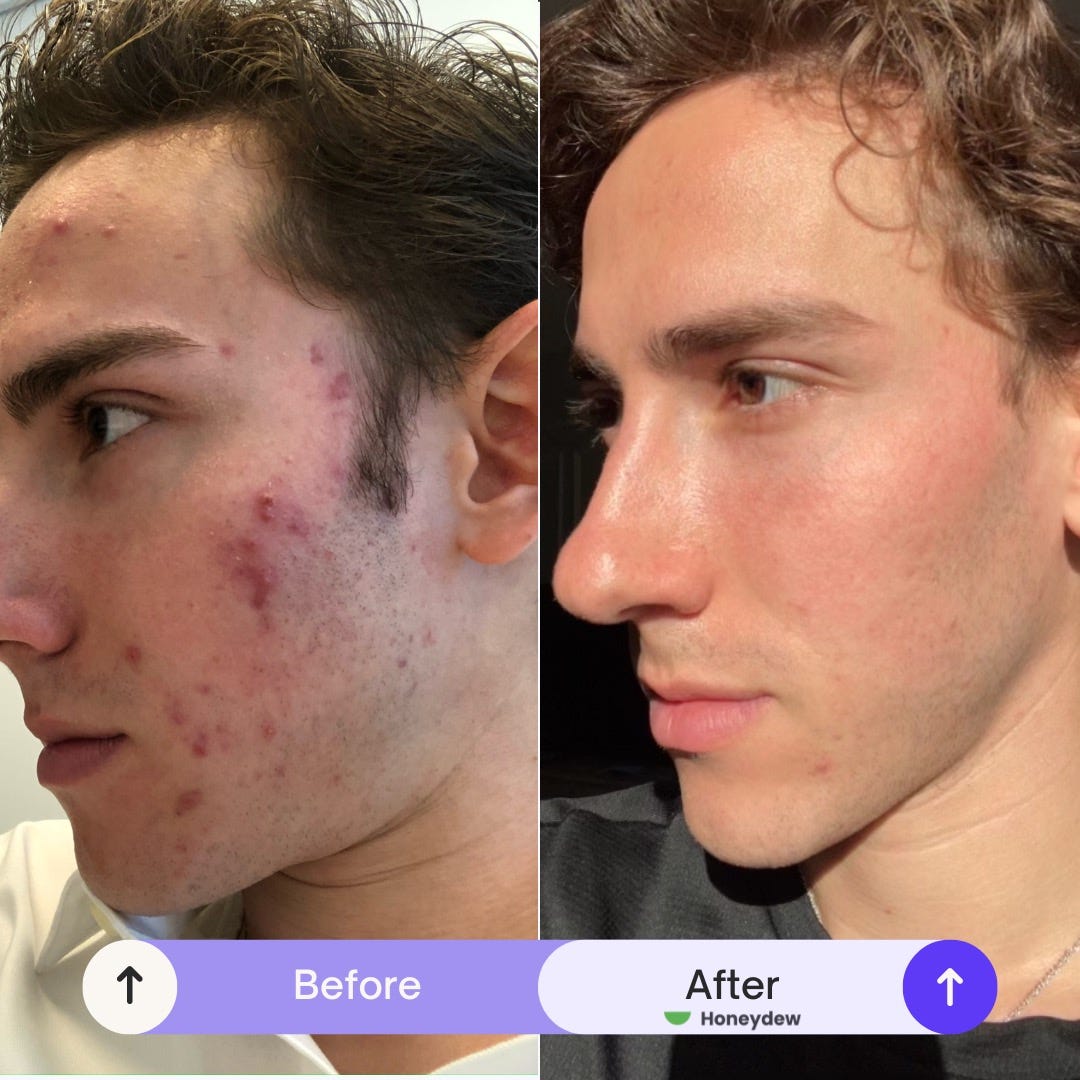

A few weeks ago I centered The Telehealth Tipping Point around David Futoran of Honeydew, a Daybreak founder solving access to dermatology care. David suffered from acne for 10 years, but every time he needed to see a dermatologist he was faced with a four month wait. When he did finally manage to see a derm, over the course of a decade he was trialed through every treatment out there: Clindamycin, Tretinoin, Dapsone, Tazorac, Doxycycline, Duricef, Epiduo—you name it. They’d work, but not for long. It wasn’t until 10 years later that he was prescribed Accutane, and it changed his life.

David teamed up with his dermatologist (name a cooler co-founder duo) to build Honeydew and solve access to care. He and Joel have both lived and breathed the pain-point, and believe deeply in their mission. Their story is a good example of being a missionary (and of founder/market fit, a related point).

4) Intellectual Horsepower

Often a good heuristic for a great founder is IQ—simple as that.

I find that the best founders have enormous intellectual horsepower, and I’m struggling to keep up with them.

5) X-Factor

Some investors like the word “killer” when assessing a founder. Is this person a “killer?” And I find that the word does help—it susses out whether a founder has a certain ambition and grit. But I prefer the term “x-factor.”

Killer can capture a bit too much of the Silicon Valley founder stereotype: hard-charging, aggressive, typically white, typically male. The Travis Kalanick type in HBO shows. X-factor is more flexible and less charged; there are many shades of entrepreneur out there.

Two talented founders I work with, for instance, saw COVID completely wipe out their revenue. They started again from scratch, with a new target customer, and rebuilt the business to over a million of ARR within a year. That’s the x-factor. Another founder I work with is so ingrained in Reddit communities about his product that people in the Reddit forum think he’s the company customer service rep, not the founder of the business. He lives and breathes the customer.

X-factor captures a founder’s tenacity—the steeliness behind her eyes that shows she’ll run through walls to build a generational company.

Final Thoughts: Asks

Part of building in public means tapping this 60,000-strong community for advice and support. Two asks for Daybreak:

We’re always on the lookout for generational entrepreneurs, no matter how early. Many of our founders we met pre-incorporation, when the business didn’t yet have a name. I’d love to meet ambitious people with big ideas.

And, of course, I’m fundraising too—and probably will never not be fundraising for the next couple decades. If you know LPs who are long-term oriented and believe in the Daybreak vision, I’d love to meet them.

Building Daybreak has given me empathy for the founder journey—the minutiae of setting up trademarks and bank accounts and fund formation docs, the grind of fundraising. It’s been energizing, thinking critically about how venture should evolve for the next generation, and I’m always open to ideas and suggestions from the community.

I’ll do “progress reports” like this one periodically, to keep me intellectually honest and to open us up to productive feedback from the ecosystem. In the meantime, we’ll keep laying the bricks 🧱

Related Digital Native Pieces

Daybreak: Venture Capital for the Next Generation (September 2023)

The Art of Early-Stage Investing (November 2023)

Seed Investing: The State of the Union (November 2023)

Two Roads Diverged: The Splitting of Venture Capital (March 2024)

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Digital Native in your inbox each week: